Nipplegate and the Effects of Implicit Vs. Explicit Sexuality in Pop Music Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Super Bowl XXXVIII National Football League Game Summary NFL Copyright © 2003 by the National Football League

Super Bowl XXXVIII National Football League Game Summary NFL Copyright © 2003 by The National Football League. All rights reserved. This summary and play-by-play is for the express purpose of assisting media in their coverage of the game; any other use of this material is prohibited without the written permission of the National Football League. Date: Sunday, 2/1/2004 Carolina Panthers At New England Patriots Start Time: 5:25 PM CST at Reliant Stadium, Houston Game Day Weather Temp: 59° F (15.0° C), Humidity: 81%, Wind: East 12 mph Played Indoor on Turf: Grass Outdoor Weather: Cloudy Officials Referee: Ed Hochuli (85) Umpire: Jeff Rice (44) Head Linesman: Mark Hittner (28) Line Judge: Ben Montgomery (117) Side Judge: Laird Hayes (125) Field Judge: Tom Sifferman (118) Back Judge: Scott Green (19) Replay Official:Larry Hill Video Operator: Lineups Carolina Panthers New England Patriots Offense Defense Offense Defense WR 87 M.Muhammad LDE 90 J.Peppers WR 83 D.Branch LE 91 B.Hamilton LT 75 T.Steussie LDT 99 B.Buckner LT 72 M.Light NT 92 T.Washington LG 78 J.James RDT 77 K.Jenkins LG 71 R.Hochstein RE 93 R.Seymour C 60 J.Mitchell RDE 93 M.Rucker C 67 D.Koppen OLB 55 W.McGinest RG 65 K.Donnalley SLB 53 G.Favors RG 63 J.Andruzzi ILB 54 T.Bruschi RT 69 J.Gross MLB 55 D.Morgan RT 68 T.Ashworth ILB 95 R.Phifer TE 84 J.Wiggins WLB 54 W.Witherspoon TE 82 D.Graham OLB 50 M.Vrabel WR 89 S.Smith LCB 24 R.Manning WR 80 T.Brown LCB 24 T.Law QB 17 J.Delhomme RCB 23 R.Howard QB 12 T.Brady RCB 38 T.Poole FB 45 B.Hoover SS 30 M.Minter RB 32 A.Smith S 26 E.Wilson -

7Th Heaven Is an Experience You Just Have to See and Hear! 7Th Heaven Has Charted #1 on the Midwest Billboard Charts Three Times in the Past Three Years

BIO 2021 7th heaven is an experience you just have to see and hear! 7th heaven has charted #1 on the Midwest Billboard Charts three times in the past three years. The band has been heard on over 7 radio stations in Chicagoland with their hits “Beautiful Life”, “This Is Where The Party’s At”, Stoplight”, "Better This Way" and "Sing". Also known for the famous "30 Songs in 30 Minutes" medley of songs from the 70's and 80's, 7th heaven has been an entertainment staple for 36 years. Playing around 200 shows a year, with an average of 100 outdoor events, 7th heaven has earned the right to say ..."We've seen a million faces and rocked them all!" • Three # 1 Hit Songs on the Billboard Charts - “Stoplight”, “Sing” & “Better This Way” • Six Major Radio Hit Songs -"This Is Where The Party's At", "Time Of Our Lives", "Beautiful Life", “Stoplight”, "Better This Way" and "Sing" • Five CD’s reached #1 on the Billboard Charts • 7th heaven’s original songs are played on many major radio stations • Opened for “Bon Jovi” & “Kid Rock” at Solider Field to 80,000 people • Opened for “Styx” to 80,000 people at a sold-out show • Written/Recorded over 5,000 songs to date • Released “Jukebox”, a collection of 700 original songs • Seen on NBC, ABC, FOX & WGN • "Beautiful Life" heard on the MTV show "Teen Mom 2" Episode 11 - Trouble in Paradise • "She Could Use a Little Sunshine" used in Ziplock TV Commercial • Started in 1985 - 34 years ago (when we were little kids) • Recognized as one of the biggest independent bands in the world • Wrote & Performed TV/Radio Commercial for “Empress Casino” • Wrote & Performed TV Commercial for “Walter E. -

The Rise of Controversial Content in Film

The Climb of Controversial Film Content by Ashley Haygood Submitted to the Department of Communication Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Communication at Liberty University May 2007 Film Content ii Abstract This study looks at the change in controversial content in films during the 20th century. Original films made prior to 1968 and their remakes produced after were compared in the content areas of profanity, nudity, sexual content, alcohol and drug use, and violence. The advent of television, post-war effects and a proposed “Hollywood elite” are discussed as possible causes for the increase in controversial content. Commentary from industry professionals on the change in content is presented, along with an overview of American culture and the history of the film industry. Key words: film content, controversial content, film history, Hollywood, film industry, film remakes i. Film Content iii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my family for their unwavering support during the last three years. Without their help and encouragement, I would not have made it through this program. I would also like to thank the professors of the Communications Department from whom I have learned skills and information that I will take with me into a life-long career in communications. Lastly, I would like to thank my wonderful Thesis committee, especially Dr. Kelly who has shown me great patience during this process. I have only grown as a scholar from this experience. ii. Film Content iv Table of Contents ii. Abstract iii. Acknowledgements I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………………1 II. Review of the Literature……………………………………………………….8 a. -

Washington Redtails Marketing Plan

Washington Redtails Marketing Plan Anne O’Dell March 16, 2015 Media, Marketing & Communications Dr. John Fenn & Mr. Darrel Kau Instructors Redtails Marketing Plan, p. 1 I. Introduction & Overview of Plan Organizational History The Washington Redskins, which shall be called “The Washington Redtails” for the duration of this plan, is a professional football of the National Football League (NFL). The team was founded in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1933 as the Boston Braves, and owner George Preston Marshall changed its name to the Redskins in 1936 just prior to its move to the Washington, DC, area. Unofficially, the name “Redskins” was chosen in honor of its then coach, William Dietz, who himself claimed Native American ancestry. Dietz had also recruited a number of Native American players to the team when it was still based in Boston as the Braves, so it was thought a fitting name and one that would differentiate the team from the Boston Braves baseball team. The organization was founded as a professional athletic organization to provide entertainment for the public. Today, it has two nonprofits under its umbrella that address various social issues in the region and nationally. This plan will primarily focus on the rebranding of the organization as it would impact its football team. Redtails Marketing Plan, p. 2 Main Goals 1. Improve Organizational Image The organization’s image is increasingly negative to those who are not fans because its current name is considered by many to be a racial slur. This is a deterrent to attracting potential fans. Changing the name to the Washington Redtails would accomplish several indirect objectives. -

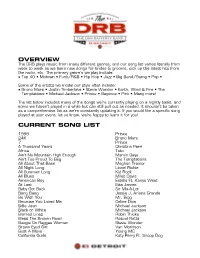

DRB Master Song List.Pages

OVERVIEW The DRB plays music from many different genres, and our song list varies literally from week to week as we learn new songs for brides & grooms, pick up the latest hits from the radio, etc. The primary genre’s we play include: • Top 40 • Motown • Funk/R&B • Hip Hop • Jazz • Big Band/Swing • Pop • Some of the artists we model our style after include: • Bruno Mars • Justin Timberlake • Stevie Wonder • Earth, Wind & Fire • The Temptations • Michael Jackson • Prince • Beyonce • Pink • Many more! The list below includes many of the songs we’re currently playing on a nightly basis, and some we haven’t played in a while but can still pull out as needed. It shouldn’t be taken as a comprehensive list as we’re constantly updating it. If you would like a specific song played at your event, let us know, we’re happy to learn it for you! CURRENT SONG LIST 1999 Prince 24K Bruno Mars 7 Prince A Thousand Years Christina Perri Africa Toto Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Marvin Gaye Ain’t Too Proud To Beg The Temptations All About That Bass Meghan Trainor All Night Long Lionel Richie All Summer Long Kid Rock All Blues Miles Davis American Boy Estelle Ft. Kanye West At Last Etta James Baby Got Back Sir Mix-A-Lot Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande Be With You Mr. Bigg Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Billie Jean Michael Jackson Black or White Michael Jackson Blurred Lines Robin Thicke Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts Boogie On Reggae Woman Stevie Wonder Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Bust A Move Young MC California Gurls Katy Perry Ft. -

NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl Has Grown to Become One of the Largest Sports Spectacles in the United States

/ The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Chelsea Police Thesis Advisor Mr. Neil Behrman Signed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2016 Expected Date of Graduation May 2016 §pCoJI U ncler.9 rod /he. 51;;:, J_:D ;l.o/80J · Z'7 The Golden Anniversary ofthe Super Bowl: A Legacy 50 Years in the Making ~0/G , PG.5 Abstract Originally known as the AFL-NFL World Championship Game, the Super Bowl has grown to become one of the largest sports spectacles in the United States. Cities across the cotintry compete for the right to host this prestigious event. The reputation of such an occasion has caused an increase in demand and price for tickets, making attendance nearly impossible for the average fan. As a result, the National Football League has implemented free events for local residents and out-of-town visitors. This, along with broadcasting the game, creates an inclusive environment for all fans, leaving a lasting legacy in the world of professional sports. This paper explores the growth of the Super Bowl from a novelty game to one of the country' s most popular professional sporting events. Acknowledgements First, and foremost, I would like to thank my parents for their unending support. Thank you for allowing me to try new things and learn from my mistakes. Most importantly, thank you for believing that I have the ability to achieve anything I desire. Second, I would like to thank my brother for being an incredible role model. -

Front of House Master Song List

CURRENT ROTATION CONTEMPORARY DANCE Love on Top – Beyoncé 24K Magic – Bruno Mars Moves Like Jagger – Maroon 5 All About That Bass – Meghan Trainor Mr. Saxobeat – Alexandra Stan All of Me – John Legend No One – Alicia Keys American Boy – Estelle & Kanye West OMG – Usher Applause – Lady Gaga One Kiss – Calvin Harris, Dua Lipa Bang Bang – Jessie J, Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj Only Girl (in the World) – Rihanna Blurred Lines – Robin Thicke On the Floor – Jennifer Lopez Boom Clap – Charlie XCX Party In The USA – Miley Cyrus Born This Way – Lady Gaga Party Rock Anthem – LMFAO Break Free – Ariana Grande Perm – Bruno Mars California Gurls – Katy Perry Poker Face – Lady Gaga Cake By The Ocean – DNCE Raise Your Glass – Pink Call Me Maybe – Carly Rae Jepsen Rather Be – Clean Bandit ft. Jess Glynn Can’t Feel My Face – The Weeknd Roar – Katy Perry Can’t Hold Us – Macklemore & Ryan Lewis Rock Your Body – Justin Timberlake Can’t Stop The Feeling – Justin Timberlake Rolling in the Deep – Adele Cheap Thrills – Sia Safe and Sound – Capital Cities Cheerleader – OMI Sexy Back – Justin Timberlake Closer – Chainsmokers ft. Halsey Shake It Off – Taylor Swift Club Can’t Handle Me – Flo Rida Shape of You – Ed Sheeran Confident – Demi Lovato Shut Up and Dance With Me – Walk the Moon Counting Stars – OneRepublic Single Ladies – Beyoncé Crazy – Gnarls Barkley Sugar – Maroon 5 Crazy In Love / Funk Medley – Beyoncé, others Suit & Tie – Justin Timberlake Despacito – Luis Fonsi ft. Justin Bieber Take Back the Night – Justin Timberlake DJ Got Us Falling in Love Again – Usher That’s What I Like – Bruno Mars Don’t Stop the Music – Rihanna There’s Nothing Holding Me Back – Shawn Mendez Domino – Jessie J This Is What You Came For – Calvin Harris ft. -

Education and the Brain: a Bridge Too Far

Education and the Brain: A Bridge Too Far j OHN T. BRUE R Educational Researcher, Vol . 26, No . 8, pp. 4-16 place, that indirectly link brain function with educational practice. There is a well-established bridge, now nearly 50 years old, between education and cognitive psychology. rain science fascinates teachers and educators, just as There is a second bridge, only around 10 years old, between it fascinates all of us. When I speak to teachers about cognitive psychology and neuroscience. This newer bridge Bapplications of cognitive science in the classroom, is allowing us to see how mental functions map onto brain there is always a question or two about the right brain ver structures. When neuroscience does begin to provide use sus the left brain and the educational promise of brain ful insights for educators about instruction and educational based curricula. I answer that these ideas have been practice, those insights will be the result of extensive traffic around for a decade, are often based on misconceptions and over this second bridge. Cognitive psychology provides the overgeneralizations of what we know about the brain, and only firm ground we have to anchor these bridges. It is the have little to offer to educators (Chipman, 1986). Educa only way to go if we eventually want to move between ed tional applications of brain science may come eventually, ucation and the brain. but as of now neuroscience has little to offer teachers in terms of informing classroom practice. There is, however, a The Neuroscience and Education Argument science of mind, cognitive science, that can serve as a basic The neuroscience and education argument relies on and science for the development of an applied science of learn embellishes three important and reasonably well-estab ing and instruction. -

Super Bowl Xxxviii

abcde • FEBRUARY 2, 2004 • SECTION C PATRIOTS PANTHERS SUPER BOWL XXXVIII Supermen II It’s a perfect ending to sequel as Vinatieri delivers another world title to Patriots By Michael Smith GLOBE STAFF Patriots 32 HOUSTON — Moments before Super Bowl Panthers 29 XXXVIII, in the privacy of the Patriots’ locker room at Reliant Stadi- um, Bill Belichick finally released his tongue from the captivity of his teeth. The reserved coach, whose every public uttering is calculated, lit a fire under his team by lighting Drive time into the Caroli- The Patriots’ winning na Panthers drive last night was during a stirring similar to the one that pregame beat the Rams in the speech. Super Bowl two years ‘‘I always be- ago. How they compare: lieve he saves 2002 2004 the best for Time 1:30 1:04 last,’’ tight end Christian Fauria Yards 53 37 said. ‘‘The Passes 5 of 8 4 of 5 speech was basi- FG 48 41 cally like, ‘We kept our mouths shut, we didn’t say any- thing, now it’s time to get to business.’ I don’t want to go into exactly what he said, but we just knew that the show was over, be- ing politically correct was over, and we knew what we had to do no matter what we were saying to the press. When we came out there, you could tell we were ready to fight those guys right on the field.’’ PATRIOTS, Page C20 GLOBE STAFF PHOTO/JIM DAVIS Tom Brady, at 26 the youngest quarterback to win two Super Bowls, hoists the Vince Lombardi Trophy. -

Eminem 1 Eminem

Eminem 1 Eminem Eminem Eminem performing live at the DJ Hero Party in Los Angeles, June 1, 2009 Background information Birth name Marshall Bruce Mathers III Born October 17, 1972 Saint Joseph, Missouri, U.S. Origin Warren, Michigan, U.S. Genres Hip hop Occupations Rapper Record producer Actor Songwriter Years active 1995–present Labels Interscope, Aftermath Associated acts Dr. Dre, D12, Royce da 5'9", 50 Cent, Obie Trice Website [www.eminem.com www.eminem.com] Marshall Bruce Mathers III (born October 17, 1972),[1] better known by his stage name Eminem, is an American rapper, record producer, and actor. Eminem quickly gained popularity in 1999 with his major-label debut album, The Slim Shady LP, which won a Grammy Award for Best Rap Album. The following album, The Marshall Mathers LP, became the fastest-selling solo album in United States history.[2] It brought Eminem increased popularity, including his own record label, Shady Records, and brought his group project, D12, to mainstream recognition. The Marshall Mathers LP and his third album, The Eminem Show, also won Grammy Awards, making Eminem the first artist to win Best Rap Album for three consecutive LPs. He then won the award again in 2010 for his album Relapse and in 2011 for his album Recovery, giving him a total of 13 Grammys in his career. In 2003, he won the Academy Award for Best Original Song for "Lose Yourself" from the film, 8 Mile, in which he also played the lead. "Lose Yourself" would go on to become the longest running No. 1 hip hop single.[3] Eminem then went on hiatus after touring in 2005. -

Where Do All the Lovers Go?”–The Cultural Politics of Public Kissing in Mumbai, India (1950–2005)

DOI: 10.1111/johs.12205 ORIGINAL ARTICLE “Where do all the lovers go?”–The Cultural Politics of Public Kissing in Mumbai, India (1950–2005) Sneha Annavarapu Doctoral Candidate, Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA Abstract Correspondence Public expressions of sexual intimacy have often been sub- Sneha Annavarapu, Doctoral Candidate, ject to moral censure and legal regulation in modern India. Department of Sociology, University of Chicago, USA. While there is literature that analyzes the cultural‐political Email: [email protected] logics of censorship and sexual illiberalism in India, the dis- courses of sympathy towards public displays of intimacy has not received as much critical attention. In this paper, I take the case of one representative discursive space offered by a popular English newspaper and show how the figure of the ‘kissing couple’ became an important entity in larger discussions about the state of urban development, the role of pleasure in the city, and the imagination of a “modern” Mumbai. “Public kissing is just not Indian”–Pramod Navalkar, Indian politician1 1 | INTRODUCTION In most Indian cities and towns, kissing in public places has been considered culturally inappropriate. The argument against men and women kissing, holding hands, and hugging in public is that it is culturally inappropriate, disrespectful to community standards, and downright ‘obscene’. Although recent protests and campaigns by urban youth2 have begun to offer a sense of organized resistance to traditional norms governing behavior in public spaces, it is common knowledge that couples engaging in ‘public displays of affection’ are often subject to moral policing by local police, political parties, and private citizens. -

HUG Holiday Songbook a Collection of Christmas Songs Used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

STRUM YULETIDE EDITION The HUG Holiday Songbook A collection of Christmas songs used by the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada All of the songs contained within this book are for research and personal use only. Many of the songs have been simplified for playing at our club meetings. General Notes: ¶ The goal in assembling this songbook was to pull together the bits and pieces of music used at the monthy gatherings of the Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) ¶ Efforts have been made to make this document as accurate as possible. If you notice any errors, please contact us at http://halifaxukulelegang.wordpress.com/ ¶ The layout of these pages was approached with the goal to make the text as large as possible while still fitting the entire song on one page ¶ Songs have been formatted using the ChordPro Format: The Chordpro-Format is used for the notation of Chords in plain ASCII-Text format. The chords are written in square brackets [ ] at the position in the song-text where they are played: [Em] Hello, [Dm] why not try the [Em] ChordPro for [Am] mat ¶ Many websites and music collections were used in assembling this songbook. In particular, many songs in this volume were used from the Christmas collections of the Seattle Ukulele Players Association (SUPA), the Bytown Ukulele Group (BUG), Richard G’s Ukulele Songbook, Alligator Boogaloo and Ukulele Hunt ¶ Ukilizer (http://www.ukulizer.com/) was used to transpose many songs into ChordPro format. ¶ Arial font was used for the song text. Chord diagrams were created using the chordette fonts from Uke Farm (http://www.ukefarm.com/chordette/) HUG Holiday Songbook - Halifax Ukulele Gang (HUG) 2015 (http://halifaxukulelegang.wordpress.com) Page 2 Table of Contents All I Want for Christmas is My Two Front Teeth.............................................................