A REDISCOVERED PAINTING of the SECOND DUKE of DEVONSHIRE from the COLLECTION of JOHN DODSLEY of SKEGBY HALL By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent

The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Surname Research The Cree Families of Newark on Trent by Mike Spathaky Cree Booklets The Cree Family History Society (now Cree Surname Research) was founded in 1991 to encourage research into the history and world-wide distribution of the surname CREE and of families of that name, and to collect, conserve and make available the results of that research. The series Cree Booklets is intended to further those aims by providing a channel through which family histories and related material may be published which might otherwise not see the light of day. Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Oadby, Leicester LE2 5RD England. Cree Surname Research CONTENTS Chart of the descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand Crees at the Muskhams - Isaac Cree and Maria Sanders The plight of single parents - the families of Joseph and Sarah Cree The open fields First published in 1994-97 as a series of articles in Cree News by the Cree Family History Society. William Cree and Mary Scott This electronic edition revised and published in 2005 by More accidents - John Cree, Ellen and Thirza Maltsters and iron founders - Francis Cree and Mary King Cree Surname Research 36 Brocks Hill Drive Fanny Cree and the boatmen of Newark Oadby Leicester LE2 5RD England © Copyright Mike Spathaky 1994-97, 2005 All Rights Reserved Elizabeth CREE b Collingham, Notts Descendants of Joshua Cree and Sarah Hand bap 10 Mar 1850 S Muskham, Notts (three generations) = 1871 Southwell+, Notts Robert -

Electoral Changes) Order 1999

451659100101-10-99 11:15:59 Pag Table: STATIN PPSysB Unit: pag1 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1999 No. 2691 LOCAL GOVERNMENT, ENGLAND The District of Bolsover (Electoral Changes) Order 1999 Made ---- 27th September 1999 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) Whereas the Local Government Commission for England, acting pursuant to section 15(4) of the Local Government Act 1992(a), has submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated November 1998 on its review of the district of Bolsover together with its recommendations: And whereas the Secretary of State has decided to give effect to those recommendations: Now, therefore, the Secretary of State, in exercise of the powers conferred on him by sections 17(b) and 26 of the Local Government Act 1992, and of all other powers enabling him in that behalf, hereby makes the following Order: Citation, commencement and interpretation 1.—(1) This Order may be cited as the District of Bolsover (Electoral Changes) Order 1999. (2) This Order shall come into force— (a) for the purpose of proceedings preliminary or relating to any election to be held on 1st May 2003, on 10th October 2002; (b) for all other purposes, on 1st May 2003. (3) In this Order— “district” means the district of Bolsover; “existing”, in relation to a ward, means the ward as it exists on the date this Order is made; any reference to the map is a reference to the map prepared by the Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions marked “Map of the District of Bolsover (Electoral Changes) Order 1999”, and deposited in accordance with regulation 27 of the Local Government Changes for England Regulations 1994(c); and any reference to a numbered sheet is a reference to the sheet of the map which bears that number. -

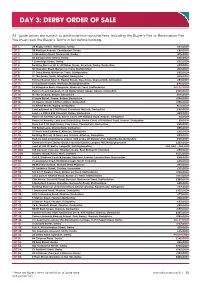

SDL EM Apr19 Lots V2.Indd

DAY 3: DERBY ORDER OF SALE All *guide prices are subject to additional non-optional fees, including the Buyer’s Fee or Reservation Fee. You must read the Buyer’s Terms in full before bidding. LOT 1. 28 Rugby Street, Wilmorton, Derby £45,000+ LOT 2. 39 Madison Avenue, Chaddesden, Derby £69,000+ LOT 3. 14 Brompton Road, Mackworth, Derby £75,000+ LOT 4. 85 Co-operative Street, Derby £50,000+ LOT 5. 1 Cummings Street, Derby £55,000+ LOT 6. Building Plot r-o 141 & 143 Baker Street, Alvaston, Derby, Derbyshire £55,000+ LOT 7. 121 Branston Road, Burton on Trent, Staffordshire £35,000+ LOT 8. 27 Duke Street, Burton on Trent, Staffordshire £65,000+ LOT 9. 15 The Green, North Wingfield, Derbyshire £35,000+ LOT 10. Former Baptist Church, Market Street, Clay Cross, Chesterfield, Derbyshire £55,000+ LOT 11. 51 Gladstone Street, Worksop, Nottinghamshire £40,000+ LOT 12. 24 Kidsgrove Bank, Kidsgrove, Stoke on Trent, Staffordshire SOLD PRIOR LOT 13. Parcel of Land between 27-35 Ripley Road, Heage, Belper, Derbyshire £150,000+ LOT 14. 15 The Orchard, Belper, Derbyshire £110,000+ LOT 15. 6 Eagle Street, Heage, Belper, Derbyshire £155,000+ LOT 16. 47 Heanor Road, Codnor, Ripley, Derbyshire £185,000+ LOT 17. 10 Alfred Street, Ripley, Derbyshire £115,000+ LOT 18. Land adjacent to 2 Mill Road, Cromford, Matlock, Derbyshire £40,000+ LOT 19. Land r-o 230 & 232 Peasehill, Ripley, Derbyshire £23,000+ LOT 20. Parcel of Amenity Land, Raven Court, Off Midland Road, Heanor, Derbyshire £8,000+ LOT 21. Parcel of Amenity Land and Outbuilding, Raven Court, off Midland Road, Heanor, Derbyshire £8,000+ LOT 22. -

District Council Election 2015

Bolsover District Council - District Council Election 2015 http://www.bolsover.gov.uk/your-council/voting-and-elections/district-... Can't find what you want, type it here... Go Home Business & Community Environment Housing & Leisure & Planning Transport & Your Council Licensing & Living & Waste Council Tax Culture Streets You are here: Your Council Voting and Elections District Council Election 2015 District Council Election 2015 District Council Election 2015 Seats won (37 available) 32 seats (Labour) 5 seats (Independent) Breakdown of results: District Council Election 2015 (07 May 2015) Barlborough (2 seats) Covering: Barlborough GILMOUR Hilary Joan Labour (Elected) 919 votes Breakdown of voting for Barlborough WATSON Brian Labour (Elected) 840 votes HUNT Maxine Yvonne Conservative 688 votes Electorate: 2495 28.1% Ballot papers issued: 1607 37.6% Total rejected papers: 14 Turnout: 64.41% 34.3% Blackwell (2 seats) Covering: Blackwell, Hilcote, Newton and Westhouses MOESBY Clive Richard Labour (Elected) 1277 votes Breakdown of voting for Blackwell BULLOCK Dexter Gene Independent (Elected) 1011 votes Bryan MUNKS Clare Labour 951 votes 29.4% Electorate: 3483 39.4% Ballot papers issued: 2219 Total rejected papers: 69 Turnout: 63.71% 31.2% Bolsover North West (2 seats) COOPER Christopher Paul Labour (Elected) 1008 votes Breakdown of voting for Bolsover North West STATTER Sue Labour (Elected) 968 votes EVANS Elaine Ann Trade Unionist and Socialists Against 359 votes 15.4% Cuts 43.2% 1 of 6 25/08/2015 15:49 Bolsover District Council - District -

College Bus Timetable 2019-20

COLLEGE BUS TIMETABLE 2019-20 In association with Correct at time of publication (July 2019) Prices and timetables are subject to change 1 Introducing Our Bus Service Bilborough College provides a heavily subsidised, dedicated and reliable bus service for students. The bus service covers areas of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire, thereby making the college accessible to students from a wide catchment area. The College offer this service in partnership with Skills Motor Coaches. Skills have provided the bus service for the college for the past six years and have a history of 90 years’ experience in passenger transport across the East Midlands. This family firm continues to provide Bilborough College with a high level of service and reliability. Stewart Ryalls is our key contact at Skills and works closely with the college in all matters relating to the bus service. We have a team at college who will help with the bus services and can be contacted on 0115 8515000 or [email protected] if you have any further queries. If you wish to apply for a bus pass, then you need to log into the College’s Wisepay system. This can be accessed from the front page of the college website. Bus passes can be found under the College Shop tab – then College Bus Passes. Select the appropriate zone (either payment in full or by Direct debit) and then select your route from the drop-down menu. Please ensure you purchase the correct zone for your stop. Second year students can apply for a bus pass anytime during the summer term. -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE of POLL and SITUATION of POLLING STATIONS Election of a Member of Parliament for the Ashf

STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED, NOTICE OF POLL AND SITUATION OF POLLING STATIONS Election of a Member of Parliament for the Ashfield Constituency Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll for the election of a Member of Parliament for the Ashfield Constituency will be held on Thursday 12 December 2019, between the hours of 7:00 am and 10:00 pm. 2. One Member of Parliament for the Ashfield Constituency is to be elected. 3. The names, home addresses and descriptions of the Candidates remaining validly nominated for election and the names of all persons signing the Candidates nomination paper are as follows: Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Names of Signatories Name of Description (if Home Address Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Proposers(+), Seconders(++) & Candidate any) Assentors Assentors Assentors ANDERSON (Address in the The Conservative Self Christine J(+) Flowers Carina(++) (+) (++) (+) (++) Lee Mansfield Party Candidate Saddington Dale Flowers Alan Constituency) Flowers Carol A Flowers Shaun A Hughes Michael Hughes Lesley M Wiggins Michael T Wiggins Carol DAUBNEY (Address in the Brexit Party Peck Andrew(+) Baillie Carl A(++) (+) (++) (+) (++) Martin Edward Ashfield Ellis Daniel Haskey Amanda Constituency) Penny Joanne Dawn Curtis Scott Marriott Simon A Breach Gary Pearce Alan P Webster Carl R FLEET (Address in the Labour Party Evans Christine L(+) Mcdowall (+) (++) (+) (++) Natalie Sarah Ashfield Blasdale David R Thomas A(++) Constituency) Flint Nicholas Mcpherson Anne Ball Kevin A Varnam Christopher -

Nottlng Hal\:Tshire, Ltt 1478 LATH RENDERS

TRADES DIBIO'l'OBY.J NOTTlNG HAl\:tSHIRE, LtT 1478 LATH RENDERS. LEATHER SELLERS. LIME BURNERS. Hartshorn M. 24A, Canal st. Nottingham Sea Curriers & Leather Sellers. Adlington Richard, High pavement, Sut Skerritt Fras. r2A, Canal st. N ottiogham ton-in-Ashfield, N ottmgham LEATHER GOODS DEALER. Ball SI. 174 Quarry rd.Bulwell,~ottngbm LAUNDRIES. Whiles Samuel, go Stodman st. Xewark Barker William, High street, Hucknall Benson Mrs. .A. 58 Crocus st.Nottinghm Torkard, 1\ottingham Carey Mrs. S. r Palmerston st.Nottnghm LEECHES & ENEMAS- Barrowcliffe George & Son, ~ormanton- Caron&Co.Croydon rd.Radfrd.Nttnghm APPLIER OF on-~oar, Loughborough Cbapman Thos. Lowdham, Nottingham · Beardsley John, Crich hme works, Wol- Connor Mrs. Anne, 164 Dame .Agnes st. Peet Mrs. E. 77 Mount st. Nottingham lat~n road, Radrord, ~ottingham Nottingham Booth Joseph, Oldcotes, Rotherham Cowpe William, Warsop rd. Mansfield; LEGGING MANUFACTURERS. BrooksbyH.Musters st.Bulwell,Nottghm & Mansfield Woodhouse India Rubber, Gutta Percha & Telegraph Carlin Miss Kezia, Q.1arry road, Bui- Crosland Frank,27 Park rw.Nottingham W()rks Co. Limited, roo & 106 Cannon well, Nottingham Daybrook Laundry (Robinson Brothers street, London E c. See advert ClarkeJ.269Quarry rd. Bulwell,~ ottg-hm & Co. ), Arnold, Nottingham Fbher Daniel, Grives, Kirkby-in-Ash- Fawkes Mrs. Elizabeth, 88 Robin Hood LEMONADE MANUF ACTRS. field, Nottingham street, Nottingham See Soda Water &c. :Manufacturers. Holmes & Co. 16 G1lead stre"t, Bulwell, Finberg 8-49 St. Ann'sWell rd. N ottinghm Nottingham Fletcher Mrs. Mary, Spital hill, Retford LIBRARIES PUBLIC. JacksonU.Mustersst.Bulweli,Nottnghm Holli~ Mrs.F.33 Glasshouse s~.~ottnghm Arnold Church Free Library (William Jenniso~ Jacob, Linby, Nottingham Nottmgham Laundry Co. -

Election of Parish Councillors

NOTICE OF ELECTION Bolsover Election of Parish Councillors for the Parishes listed below Number of Parish Councillors Parishes to be elected Ault Hucknall Ten Old Bolsover (West Ward) Four Barlborough Eight Pinxton (Broadmeadows Ward) Three Blackwell (Blackwell Ward) Three Pinxton (Pinxton Ward) Nine Blackwell (Hilcote Ward) Two Pleasley Ten Blackwell (Newton Ward) Five Scarcliffe (North Ward) Four Blackwell (Westhouses Ward) Two Scarcliffe (South Ward) Four Clowne (North Ward) Six Shirebrook (East Ward) Three Clowne (South Ward) Six Shirebrook (North Ward) Three Elmton with Creswell Eleven Shirebrook (North West Ward) Three Glapwell Ten Shirebrook (South East Ward) Four Hodthorpe and Belph Seven Shirebrook (South West Ward) Three Langwith (Bassett Ward) Four South Normanton (East Ward) Three Langwith (Bathurst Ward) Four South Normanton (West Ward) Seven Langwith (Poulter Ward) Four South Normanton Central Ward Three Old Bolsover (Central Ward) Three Tibshelf Eleven Old Bolsover (East Ward) Four Whitwell Eight Old Bolsover (North Ward) One 1. Forms of nomination for Parish Elections may be obtained from Clerks to Parish Councils or The Arc, High Street, Clowne, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, S43 4JY from the Returning Officer who will, at the request of an elector for any electoral area prepare a nomination paper for signature. 2. Please arrange an appointment for the checking of nomination papers by contacting the Head of Election Services on 01246 242427 or 01246 242435. 3. Nomination papers must be delivered to the Returning Officer, The Arc, High Street, Clowne, Chesterfield, Derbyshire, S43 4JY on any day after the date of this notice but no later than 4 pm on Thursday, 9th April 2015. -

North Derbyshire Local Development Frameworks: High Peak and Derbyshire Dales Stage 2: Traffic Impacts of Proposed Development

Derbyshire County Council North Derbyshire Local Development Frameworks: High Peak and Derbyshire Dales Stage 2: Traffic Impacts of Proposed Development Draft June 2010 North Derbyshire Local Development Frameworks Stage 2: Traffic Impacts of Proposed Development Revision Schedule Draft June 2010 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 June 10 Draft Daniel Godfrey Kevin Smith Kevin Smith Senior Transport Planner Associate Associate Scott Wilson Dimple Road Business Centre Dimple Road This document has been prepared in accordance with the scope of Scott Wilson's MATLOCK appointment with its client and is subject to the terms of that appointment. It is addressed Derbyshire to and for the sole and confidential use and reliance of Scott Wilson's client. Scott Wilson accepts no liability for any use of this document other than by its client and only for the DE4 3JX purposes for which it was prepared and provided. No person other than the client may copy (in whole or in part) use or rely on the contents of this document, without the prior written permission of the Company Secretary of Scott Wilson Ltd. Any advice, opinions, Tel: 01246 218 300 or recommendations within this document should be read and relied upon only in the context of the document as a whole. The contents of this document do not provide legal Fax : 01246 218 301 or tax advice or opinion. © Scott Wilson Ltd 2010 www.scottwilson.com North Derbyshire Local Development Frameworks Stage 2: Traffic Impacts of Proposed Development Table of Contents 1 Introduction......................................................................................... 1 1.1 The Local Development Framework Process.................................................................. -

Timetable of C Card Registration and Pick up Sites in Nottinghamshire

TIMETABLE OF C CARD REGISTRATION AND PICK UP SITES IN NOTTINGHAMSHIRE C Card Site Opening Times Registration or Pick Up 1. ASHFIELD Acre YPC Tuesday, Wednesday & Registration and Pick Up Morley Street Thursday 7.00 pm to 9.00 pm. Kirkby-in-Ashfield SESions Team Drop-in Nottinghamshire Thursday 12.25 pm- 1.10 pm NG17 7AZ Ashfield HPS (Outram Street) Available to service users and Registration and Pick Up Outram Street Centre their visitiors. 24 hour Old Chapel House supported housing service. Sutton-in-Ashfield Nottinghamshire NG17 4AX Ashfield School School Nurse Drop in. Registration and Pick Up Sutton road Students Only Kirkby-in-Ashfield Nottinghamshire NG17 8HP Brierley Park Health Centre By appointment, open Monday Registration and Pick Up 127 Sutton Road to Friday 7.00 am - 6.30 pm. Huthwaite Sutton-in-Ashfield Nottinghamshire NG17 2NF Harts Chemists Monday to Friday 8.30 am to Pick Up Point 106/110 Watnall Rd 6.00 pm Hucknall Nottinghamshire NG15 7JW Holgate Academy Thursday lunchtime 12.25 to Registration and Pick Up Nabbs Lane 1.05 pm School Nurse drop-in. Hucknall Pupils of school only. Nottinghamshire NG15 9PX Hucknall Health Centre Monday to Friday 8.30 am to Registration and Pick Up Curtis Street 6.30 pm. Pick up from Hucknall reception. Nottinghamshire NG15 7JE Hucknall Interchange Tuesday, Wednesday and Registration and Pick Up 69 Linby Rd Friday 7.00 pm to 9.30 pm Hucknall Nottinghamshire NG15 7TX Kirkby College Wednesday lunchtime drop- Registration and Pick Up Tennyson Street ins Kirkby in Ashfield Nottinghamshire NG17 7DH TIMETABLE OF C CARD REGISTRATION AND PICK UP SITES IN NOTTINGHAMSHIRE C Card Site Opening Times Registration or Pick Up Nabbs Lane Pharmacy Monday to Friday 9.00 am - Registration and Pick Up 83 Nabbs Lane 6.00 pm. -

Blackwell Parish Council

BLACKWELL PARISH COUNCIL Minutes of a Meeting of the Blackwell Parish Council held at Newton Community Centre, Newton on Monday 2 March 2015 at 7pm. PRESENT Councillor N J B Willens (Chairman) Councillors: D G B Bullock: I G Cox: C R Moesby: Mrs C Munks: I J A Newham: R A Poulter R J Sainsbury: B Stocks: A F Tomlinson: and L Walker 237/2014 ALSO PRESENT Three Parishioners. 238/2014 APOLOGIES FOR ABSENCE There were no apologies for absence 239/2014 DISCLOSABLE PECUNIARY INTERESTS/CODE OF CONDUCT The Chairman reminded Council Members to declare the existence and nature of any disclosable pecuniary interest they had in subsequent Agenda items in accordance with the Parish Councils Code of Conduct. Interest that became apparent at a later stage in the proceedings could be declared at that time. 240/2014 PUBLIC SPEAKING (20 MINUTES) Mr B Clarkson Blackwell advised Council Members of a number of pot holes on Fordbridge Lane, Black well and he was advised by Councillor C R Moesby, in his capacity as County Councillor to contact Derbyshire County Council Highways Departments dedicated line with regard to dealing with pot holes which is 01629 533190. Councillors B Stocks and L Walker also expressed concerns with regard to a number of pot holes on Hilcote Lane and New Lane, Hilcote and they were further advised by Councillor C R Moesby, in his capacity as County Councillor to contact the Derbyshire County Council Highways Department 01629 533190 to report the complaint. 241/2014 BLACKWELL RESIDENTS ACTION GROIUP Councillor I J A Newham advised Council Members: 3 1. -

The Benefice of St. Andrew's Church, Skegby with All Saints' Church, Stanton Hill and St. Katherine's Church, Teversal

The Benefice of St. Andrew’s Church, Skegby with All Saints’ Church, Stanton Hill and St. Katherine’s Church, Teversal. Parish Profile Job Description … To build on the existing cohesion for mission in these linked but distinctive communities To bring insight and strategies for growing our churches in line with the Diocesan Vision To lead the current ministerial team and enjoy working with a leadership mature in their faith To bring vision and an openness to the prompting of the Holy Spirit as we seek new ways of growing wider in our community outreach To serve as a Governor in our church school and as a trustee on parish charities To engage with local community as an energetic and passionate advocate for those in need. Person Specification … You will enjoy the prospect of building on good leadership and see new possibilities. You will relish the possibility of being a spiritual leader and fellow disciple. You will be someone who enjoys engaging with community life and the daily attention to people’s cares and concerns. You will be committed to your own learning and the nurture of others. You will be happy to take note of what our children are saying!! “You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart………” Matthew 22:36 - 40 The children said, “I would like my Vicar to be someone who…..” “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations……” Matthew 28:19,20 The Vicarage is set in spacious grounds adjacent to St. Andrew’s Church. It was erected in 1973 and has been well maintained; solar panels have been recently installed.