And Northern Spotted Owls in Particular

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Transcriptome of the Avian Malaria Parasite Plasmodium

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/072454; this version posted August 31, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 The Transcriptome of the Avian Malaria Parasite 2 Plasmodium ashfordi Displays Host-Specific Gene 3 Expression 4 5 6 7 8 Running title 9 The Transcriptome of Plasmodium ashfordi 10 11 Authors 12 Elin Videvall1, Charlie K. Cornwallis1, Dag Ahrén1,3, Vaidas Palinauskas2, Gediminas Valkiūnas2, 13 Olof Hellgren1 14 15 Affiliation 16 1Department of Biology, Lund University, Lund, Sweden 17 2Institute of Ecology, Nature Research Centre, Vilnius, Lithuania 18 3National Bioinformatics Infrastructure Sweden (NBIS), Lund University, Lund, Sweden 19 20 Corresponding authors 21 Elin Videvall ([email protected]) 22 Olof Hellgren ([email protected]) 23 24 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/072454; this version posted August 31, 2016. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 25 Abstract 26 27 Malaria parasites (Plasmodium spp.) include some of the world’s most widespread and virulent 28 pathogens, infecting a wide array of vertebrates. Our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms these 29 parasites use to invade and exploit hosts other than mice and primates is, however, extremely limited. 30 How do Plasmodium adapt to individual hosts and to the immune response of hosts throughout an 31 infection? To better understand parasite plasticity, and identify genes that are conserved across the 32 phylogeny, it is imperative that we characterize transcriptome-wide gene expression from non-model 33 malaria parasites in multiple host individuals. -

The Black Flies of Maine

THE BLACK FLIES OF MAINE L.S. Bauer and J. Granett Department of Entomology University of Maine at Orono, Orono, ME 04469 Maine Life Sciences and Agriculture Experiment Station Technical Bulletin 95 May 1979 LS-\ F.\PFRi\ii-Nr Si \IION TK HNK \I BUI I HIN 9? ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We wish to thank Dr. Ivan McDaniel for his involvement in the USDA-funding of this project. We thank him for his assistance at the beginning of this project in loaning us literature, equipment, and giving us pointers on taxonomy. He also aided the second author on a number of collection trips and identified a number of collection specimens. We thank Edward R. Bauer, Lt. Lewis R. Boobar, Mr. Thomas Haskins. Ms. Leslie Schimmel, Mr. James Eckler, and Mr. Jan Nyrop for assistance in field collections, sorting, and identifications. Mr. Ber- nie May made the electrophoretic identifications. This project was supported by grant funds from the United States Department of Agriculture under CSRS agreement No. 616-15-94 and Regional Project NE 118, Hatch funds, and the Maine Towns of Brad ford, Brownville. East Millinocket, Enfield, Lincoln, Millinocket. Milo, Old Town. Orono. and Maine counties of Penobscot and Piscataquis, and the State of Maine. The electrophoretic work was supported in part by a faculty research grant from the University of Maine at Orono. INTRODUCTION Black flies have been long-time residents of Maine and cause exten sive nuisance problems for people, domestic animals, and wildlife. The black fly problem has no simple solution because of the multitude of species present, the diverse and ecologically sensitive habitats in which they are found, and the problems inherent in measuring the extent of the damage they cause. -

Review and Phylogeny of Lutzsimulium (Diptera: Simuliidae)

ZOOLOGIA 27 (5): 761–788, October, 2010 doi: 10.1590/S1984-46702010000500014 Review and phylogeny of Lutzsimulium (Diptera: Simuliidae) Leonardo H. Gil-Azevedo Fundação Oswaldo Cruz, Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, Laboratório de Simulídeos e Oncocercose. Avenida Brasil 4365, Manguinhos, Caixa Postal 926, 21045-900 Rio de Janeiro, RJ, Brazil. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Lutzsimulium d’Andretta Jr & Vulcano, 1947 is an enigmatic South American genus with four species: L. flavopubescens Lutz, 1910, L. hirticosta Lutz, 1909, L. pernigrum Lutz, 1910 and L. simplicicolor Lutz, 1910. It can be diagnosed by median arms of furcasternum with projections; subbasal tooth of the claw reduced; wing basal cell absent; spermatheca with net-like structure; apex of trichomes coiled (pupa); gill with two main trunks (pupa); antennomere 3 equal to or longer than 1+2 (larva); hypostomal teeth reduced (larva); postgenal cleft deep (larva). A morphological cladistic analysis under equal weights, with the four Lutzsimulium species and six outgroups, resulted in two most parsimonious trees, with 81 steps, CI = 0.61 and RI = 0.68. The monophyly of the genus is corroborated, supported by 15 synapomorphies, therefore it is proposed that Kempfsimulium Py-Daniel & Nunes de Mello, 1982 is synonymous of Lutzsimulium. Also the status of Araucnephia Wygodzinsky & Coscarón, 1973 and Araucnephioides Wygodzinsky & Coscarón, 1973 are revalidated, because they do not form a monophyletic group with Lutzsimulium. All the species of Lutzsimulium are revised, with redescriptions, illustrations and identification keys for adults, pupa and larva. The male and larva of L. flavopubescens are described for the first time. KEY WORDS. Argentina; black-fly; Brazil; cladistics; Culicomorpha; Insecta; Neotropical Region; taxonomy. -

Black-Flies and Leucocytozoon Spp. As Causes of Mortality in Juvenile Great Horned Owls in the Yukon, Canada

Black-flies and Leucocytozoon spp. as Causes of Mortality in Juvenile Great Horned Owls in the Yukon, Canada D. Bruce Hunter1, Christoph Rohner2, and Doug C. Currie3 ABSTRACT.—Black fly feeding and infection with the blood parasite Leucocytozoon spp. caused mortality in juvenile Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) in the Yukon, Canada during 1989-1990. The mortality occurred during a year of food shortage corresponding with the crash in snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) populations. We postulate that the occurrence of disease was mediated by reduced food availability. Rohner (1994) evaluated the numerical re- black flies identified from Alaska, USA and the sponse of Great Horned Owls (Bubo virginianus) Yukon Territory, Canada, 36 percent are orni- to the snowshoe hare (Lepus americanus) cycle thophilic, 39 percent mammalophilic and 25 from 1988 to 1993 in the Kluane Lake area of percent autogenous (Currie 1997). Numerous southwestern Yukon, Canada. The survival of female black flies were obtained from the car- juvenile owls was very high during 1989 and casses of the juvenile owls, but only 45 of these 1990, both years of abundant hare populations. were sufficiently well preserved for identifica- Survival decreased in 1991, the first year of the tion. They belonged to four taxa as follows: snowshoe hare population decline (Rohner and Helodon (Distosimulium) pleuralis (Malloch), 1; Hunter 1996). Monitoring of nest sites Helodon (Parahelodon) decemarticulatus combined with tracking of individuals by radio- (Twinn), 3; Simulium (Eusimulium) aureum Fries telemetry provided us with carcasses of 28 ju- complex, 3; and Simulium (Eusimulium) venile owls found dead during 1990 and 1991 canonicolum (Dyar and Shannon) complex, 38 (Rohner and Doyle 1992). -

Bird List Column A: We Should Encounter (At Least a 90% Chance) Column B: May Encounter (About a 50%-90% Chance) Column C: Possible, but Unlikely (20% – 50% Chance)

THE PHILIPPINES Prospective Bird List Column A: we should encounter (at least a 90% chance) Column B: may encounter (about a 50%-90% chance) Column C: possible, but unlikely (20% – 50% chance) A B C Philippine Megapode (Tabon Scrubfowl) X Megapodius cumingii King Quail X Coturnix chinensis Red Junglefowl X Gallus gallus Palawan Peacock-Pheasant X Polyplectron emphanum Wandering Whistling Duck X Dendrocygna arcuata Eastern Spot-billed Duck X Anas zonorhyncha Philippine Duck X Anas luzonica Garganey X Anas querquedula Little Egret X Egretta garzetta Chinese Egret X Egretta eulophotes Eastern Reef Egret X Egretta sacra Grey Heron X Ardea cinerea Great-billed Heron X Ardea sumatrana Purple Heron X Ardea purpurea Great Egret X Ardea alba Intermediate Egret X Ardea intermedia Cattle Egret X Ardea ibis Javan Pond-Heron X Ardeola speciosa Striated Heron X Butorides striatus Yellow Bittern X Ixobrychus sinensis Von Schrenck's Bittern X Ixobrychus eurhythmus Cinnamon Bittern X Ixobrychus cinnamomeus Black Bittern X Ixobrychus flavicollis Black-crowned Night-Heron X Nycticorax nycticorax Western Osprey X Pandion haliaetus Oriental Honey-Buzzard X Pernis ptilorhynchus Barred Honey-Buzzard X Pernis celebensis Black-winged Kite X Elanus caeruleus Brahminy Kite X Haliastur indus White-bellied Sea-Eagle X Haliaeetus leucogaster Grey-headed Fish-Eagle X Ichthyophaga ichthyaetus ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. 109 ● Tucson ● AZ ● 85712 ● www.wingsbirds.com -

A New Species of Sarcocystis in the Brain of Two Exotic Birds1

© Masson, Paris, 1979 Annales de Parasitologie (Paris) 1979, t. 54, n° 4, pp. 393-400 A new species of Sarcocystis in the brain of two exotic birds by P. C. C. GARNHAM, A. J. DUGGAN and R. E. SINDEN * Imperial College Field Station, Ashurst Lodge, Ascot, Berkshire and Wellcome Museum of Medical Science, 183 Euston Road, London N.W.1., England. Summary. Sarcocystis kirmsei sp. nov. is described from the brain of two tropical birds, from Thailand and Panama. Its distinction from Frenkelia is considered in some detail. Résumé. Une espèce nouvelle de Sarcocystis dans le cerveau de deux Oiseaux exotiques. Sarcocystis kirmsei est décrit du cerveau de deux Oiseaux tropicaux de Thaïlande et de Panama. Les critères de distinction entre cette espèce et le genre Frenkelia sont discutés en détail. In 1968, Kirmse (pers. comm.) found a curious parasite in sections of the brain of an unidentified bird which he had been given in Panama. He sent unstained sections to one of us (PCCG) and on examination the parasite was thought to belong to the Toxoplasmatea, either to a species of Sarcocystis or of Frenkelia. A brief description of the infection was made by Tadros (1970) in her thesis for the Ph. D. (London). The slenderness of the cystozoites resembled those of Frenkelia, but the prominent spines on the cyst wall were more like those of Sarcocystis. The distri bution of the cystozoites within the cyst is characteristic in that the central portion is practically empty while the outer part consists of numerous pockets of organisms, closely packed together. -

Some Remarks on the Genus Leucocytozoon

63 SOME REMAKES ON THE GENUS LEUCOCYTOZOON. BY C. M. WENYON, B.SC, M.B., B.S. Protozoologist to the London School of Tropical Medicine. NOTE. A reply to the criticisms contained in Dr Wenyon's paper will be published by Miss Porter in the next number of " Parasitology". A GOOD deal of doubt still exists in many quarters as to the exact meaning of the term Leucocytozoon applied to certain Haematozoa. The term Leucocytozoaire was first used by Danilewsky in writing of certain parasites he had found in the blood of birds. In a later publication he uses the term Leucocytozoon for the same parasites though he does not employ it as a true generic title. In this latter sense it was first employed by Ziemann who named the parasite of an owl Leucocytozoon danilewskyi, thus establishing this parasite the type species of the new genus Leucocytozoon. It is perhaps hardly necessary to mention that Danilewsky and Ziemann both used this name because they considered the parasite in question to inhabit a leucocyte of the bird's blood. There has arisen some doubt as to the exact nature of this host-cell. Some authorities consider it to be a very much altered red blood corpuscle, some perhaps more correctly an immature red blood corpuscle, while others adhere to the original view of Danilewsky as to its leucocytic nature. It must be clearly borne in mind that the nature of the host-cell does not in any way affect the generic name Leucocytozoon. If it could be conclusively proved that the host-cell is in every case a red blood corpuscle the name Leucocytozoon would still remain as the generic title though it would have ceased to be descriptive. -

Bird Checklists of the World Country Or Region: Ghana

Avibase Page 1of 24 Col Location Date Start time Duration Distance Avibase - Bird Checklists of the World 1 Country or region: Ghana 2 Number of species: 773 3 Number of endemics: 0 4 Number of breeding endemics: 0 5 Number of globally threatened species: 26 6 Number of extinct species: 0 7 Number of introduced species: 1 8 Date last reviewed: 2019-11-10 9 10 Recommended citation: Lepage, D. 2021. Checklist of the birds of Ghana. Avibase, the world bird database. Retrieved from .https://avibase.bsc-eoc.org/checklist.jsp?lang=EN®ion=gh [26/09/2021]. Make your observations count! Submit your data to ebird. -

Studies on Blood Parasites of Birds in Coles County, Illinois Edward G

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1968 Studies on Blood Parasites of Birds in Coles County, Illinois Edward G. Fox Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Zoology at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Fox, Edward G., "Studies on Blood Parasites of Birds in Coles County, Illinois" (1968). Masters Theses. 4148. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/4148 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #3 To: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. Subject: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements. Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because------------- Date Author STUDIES CB BLOOD PARA.SIDS 0, BlRDS Xlf COLES COUIITY, tI,JJJIOXI (TITLE) BY Bdward G. iox B. s. -

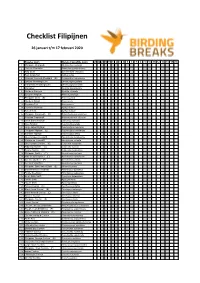

Checklist Filipijnen

Checklist Filipijnen 26 januari t/m 17 februari 2020 Engelse naam Wetenschappelijke naam 27 28 29 30 31 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 1 Philippine Megapode Megapodius cumingii 2 Chinese Francolin Francolinus pintadeanus 3 King Quail Excalfactoria chinensis 4 Red Junglefowl Gallus gallus 5 Palawan Peacock-Pheasant (E) Polyplectron napoleonis 6 Spotted Whistling Duck Dendrocygna guttata 7 Wandering Whistling Duck Dendrocygna arcuata 8 Garganey Spatula querquedula 9 Northern Shoveler Spatula clypeata 10 Eurasian Wigeon Mareca penelope 11 Philippine Duck (E) Anas luzonica 12 Northern Pintail Anas acuta 13 Eurasian Teal Anas crecca 14 Common Pochard Aythya ferina 15 Tufted Duck Aythya fuligula 16 Philippine Frogmouth (E) Batrachostomus septimus 17 Palawan Frogmouth Batrachostomus chaseni 18 Great Eared Nightjar Lyncornis macrotis 19 Grey Nightjar Caprimulgus jotaka 20 Large-tailed Nightjar Caprimulgus macrurus 21 Philippine Nightjar (E) Caprimulgus manillensis 22 Savanna Nightjar Caprimulgus affinis 23 Grey-rumped Treeswift Hemiprocne longipennis 24 Whiskered Treeswift Hemiprocne comata 25 Grey-rumped Swiftlet (E) Collocalia marginata 26 Ridgetop Swiftlet (E) Collocalia isonota 27 Pygmy Swiftlet (E) Collocalia troglodytes 28 Philippine Swiftlet (E) Aerodramus mearnsi 29 Whitehead's Swiftlet (E) Aerodramus whiteheadi 30 Ameline Swiftlet (E) Aerodramus amelis 31 Germain's Swiftlet Aerodramus germani 32 Philippine Spine-tailed Swift (E) Mearnsia picina 33 Brown-backed Needletail Hirundapus giganteus 34 Purple Needletail Hirundapus celebensis -

Ecology and Evolution of Malarial Parasites In

ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF MALARIAL PARASITES IN VERTEBRATE HOSTS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Holly Lynn Lutz August 2016 © Holly Lynn Lutz 2016 ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTION OF MALARIAL PARASITES IN VERTEBRATE HOSTS Holly Lynn Lutz, Ph.D. Cornell University 2016 This dissertation represents a culmination of extensive field work and collections of African vertebrates and their symbionts, as well as experimental studies carried out in the laboratory. Field work was conducted primarily in the East African countries of Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, and Uganda. Throughout these expeditions, efforts were made to improve field protocols for the comprehensive sampling of wild vertebrates and their symbionts, with particular focus on the sampling of avian blood parasites (haematozoa), ectoparasites (arthropods), endoparasites (helminths), and microbial symbionts (bacteria and viruses). This dissertation therefore includes a chapter with detailed guidelines and protocols for sampling avian symbionts based on these experiences. Following chapters rely on data from both field collections and laboratory experiments, which provide a foundation for addressing the ecology, systematics, and molecular evolution of malarial parasites in vertebrate hosts. Specifically, haemosporidian data from 2,539 Afrotropical birds and small mammals (bats, rodents, and shrews) collected during field inventories were used to (1) test hypotheses linking host life history traits and host ecology to patterns of infection by three haemosporidian parasite genera in birds (Plasmodium, Haemoproteus, and Leucocytozoon), and (2) re-evaluate the molecular phylogeny of the order Haemosporida by incorporating existing genomic data from haemosporidian parasites with data from novel parasite lineages infecting major vertebrate host groups, including birds, mammals, and reptiles. -

Ultimate Philippines

The bizarre-looking Philippine Frogmouth. Check those eyes! (Dani Lopez-Velasco). ULTIMATE PHILIPPINES 14 JANUARY – 4/10/17 FEBRUARY 2017 LEADER: DANI LOPEZ-VELASCO This year´s Birdquest “Ultimate Philippines” tour comprised of the main tour and two post-tour extensions, resulting in a five-week endemics bonanza. The first three weeks focused on the better-known islands of Luzon, Palawan and Mindanao, and here we had cracking views of some of those mind-blowing, world´s must-see birds, including Philippine Eagle, Palawan Peacock-Pheasant, Wattled Broadbill and Azure- breasted Pitta, amongst many other endemics. The first extension took us to the central Visayas where exciting endemics such as the stunning Yellow-faced Flameback, the endangered Negros Striped Babbler or the recently described Cebu Hawk-Owl were seen well, and we finished with a trip to Mindoro and remote Northern Luzon, where Scarlet-collared Flowerpecker and Whiskered Pitta delighted us. 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Ultimate Philippines www.birdquest-tours.com Our success rate with the endemics– the ones you come to the Philippines for- was overall very good, and highlights included no less than 14 species of owl recorded, including superb views of Luzon Scops Owl, 12 species of beautiful kingfishers, including Hombron´s (Blue-capped Wood) and Spotted Wood, 5 endemic racket-tails and 9 species of woodpeckers, including all 5 flamebacks. The once almost impossible Philippine Eagle-Owl showed brilliantly near Manila, odd looking Philippine and Palawan Frogmouths gave the best possible views, impressive Rufous and Writhed Hornbills (amongst 8 species of endemic hornbills) delighted us, and both Scale-feathered and Rough-crested (Red-c) Malkohas proved easy to see.