A Dog's Got Personality: a Cross-Species Comparative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The 7Pm Zoomies I Don’T Know What It Is

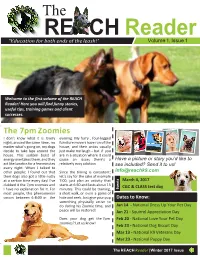

The REACH Reader Volume 1. Issue 1 Welcome to the first volume of the REACH Reader! Here you will find funny stories, useful tips, training games and client successes. The 7pm Zoomies I don’t know what it is. Every evening. My furry , four-legged night, around the same time, no furniture movers have run of the matter what’s going on, my dogs house, and their antics usually decide to take laps around the just make me laugh – but if you house. This sudden burst of are in a situation where it could energy overtakes them, and they cause an issue; there’s a Have a picture or story you’d like to act like lunatics for a few minutes relatively easy solution. see included? Send it to us! every night. When I talked to other people; I found out that Since the timing is consistent; [email protected] their dogs also got a little nutty let’s say for the sake of example at a certain time every day! I’ve 7:00, just plan an activity that ts March 4, 2017 n dubbed it the 7pm zoomies and starts at 6:50 and lasts about 15 e v CGC & CLASS test day I have no explanation for it. For minutes. This could be training, E most people, this phenomenon a short walk, or even a game of occurs between 6-8:00 in the hide and seek. Just give your pup Dates to Know: something physically active to do during his Zoomie time, and Jan 14 - National Dress Up Your Pet Day peace will be restored! Jan 21 - Squirrel Appreciation Day Does your dog get the 7pm Feb 20 - National Love Your Pet Day zoomies? Let us know! Feb 23 - National Dog Biscuit Day Mar 13 - National K9 Veterans Day Mar 23 - National Puppy Day The REACH Reader | Winter 2017 Issue 1 The Reach Reader | Quarterly Newsletter Story Some days… I’m a trainer, so I must have some pretty awesome dogs, right? Well – I do have awesome dogs, but they aren’t perfect. -

Your New Rescue Dog

National Great Pyrenees Rescue - 1 - Your New Rescue Dog Thank you giving a home to a rescue dog! By doing so, you have saved a life. It takes many volunteers and tremendous amounts of time and effort to save each dog. Please remember each and every one of them is special to us and we want the best for them. As such, we want you to be happy with your dog. No dog is perfect, and a rescue dog may require time and patience to reach their full potential, but they will reward you a hundred times over. Be patient, be firm, but most of all have fun and enjoy your new family member! Meeting a transport Traveling on a commercial or multi-legged volunteer transport is very stressful for dogs. Many will not eat or drink while traveling, so bring water and a bowl to the meeting place. Have a leash and name tag ready with your contact info and put these on the dog ASAP. No one wants to see a dog lost, especially after going through so much to get to you. Take your new Pyr for a walk around the parking lot. It’s tempting to cuddle a new dog, but what they really need is some space. They will let you know when they are ready for attention. Puppies often need to be carried at first, but they do much better once they feel grass under their feet. Young puppies should not be placed on the ground at transport meeting locations. Their immune system may not be ready for this. -

Developing Dog Biscuits from Industrial By-Product Kyriaki Chanioti

Developing Dog Biscuits from Industrial by-product Kyriaki Chanioti DIVISION OF PACKAGING LOGISTICS | DEPARTMENT OF DESIGN SCIENCES FACULTY OF ENGINEERING LTH | LUND UNIVERSITY 2019 MASTER THESIS This Master’s thesis has been done within the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree FIPDes, Food Innovation and Product Design. The European Commission support for the production of this publication does not constitute an endorsement of the contents which reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. Developing Dog Biscuits from Industrial by-product From an idea to prototype Kyriaki Chanioti Developing Dog Biscuit from Industrial by-product From an idea to prototype Copyright © 2019 Kyriaki Chanioti Published by Division of Packaging Logistics Department of Design Sciences Faculty of Engineering LTH, Lund University P.O. Box 118, SE-221 00 Lund, Sweden Subject: Food Packaging Design (MTTM01) Division: Packaging Logistics Supervisor: Daniel Hellström Co-supervisor: Federico Gomez Examiner: Klas Hjort This Master´s thesis has been done within the Erasmus Mundus Joint Master Degree FIPDes, Food Innovation and Product Design. www.fipdes.eu ISBN 978-91-7895-210-6 Acknowledgments It is happening, I am graduating FIPDes with the most fascinating thesis project that could ever imagine! However, I would like to firstly thank all the people in FIPDes consortium who believed in me and made my dream come true. The completion of this amazing project would not have been possible without the support, guidance and positive attitude of my supervisor, Daniel Hellström and my co-supervisor, Federico Gomez for making my stay in Kemicentrum welcoming and guiding me through the process. -

2018 Ohio State Fair Junior Fair Dog Show Rules AKC Trick Dog AKC

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION 2018 Ohio State Fair Junior Fair Dog Show Rules for AKC Trick Dog and AKC Canine Good Citizen ohio4h.org CFAES provides research and related educational programs to clientele on a nondiscriminatory basis. For more information: go.osu.edu/cfaesdiversity. Ohio State Fair Junior Fair Dog Show Rules AKC Trick Dog and AKC Canine Good Citizen Table of Contents 2018 Ohio State Fair Junior Fair Dog Show General Rules Preface………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 4 Project Eligibility………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 4 Dog Eligibility………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Ownership Requirements……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 5 Definitions of Ownership…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Training……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Showing………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Safety and Sportsmanship…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 6 Permission to Participate in Ohio 4-H Dog Activities Disclosure and Release of Claims……………………………. 6 Misbehavior and Excusals for Dogs on the Fairgrounds, Show Area, or in the Show Ring…………………………. 7 Unsportsmanlike Conduct………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 Other…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 7 License Requirements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Health Requirements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Scores and Score Sheets………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 9 State Fair Championship Title………………………………………………………………………………………………. 9 4-H Exhibitor Versatility -

The Intelligence of Dogs a Guide to the Thoughts, Emotions, and Inner Lives of Our Canine

Praise for The Intelligence of Dogs "For those who take the dog days literally, the best in pooch lit is Stanley Coren’s The Intelligence of Dogs. Psychologist, dog trainer, and all-around canine booster, Coren trots out everyone from Aristotle to Darwin to substantiate the smarts of canines, then lists some 40 commands most dogs can learn, along with tests to determine if your hairball is Harvard material.” —U.S. News & World Report "Fascinating . What makes The Intelligence of Dogs such a great book, however, isn’t just the abstract discussions of canine intelli gence. Throughout, Coren relates his findings to the concrete, dis cussing the strengths and weaknesses of various breeds and including specific advice on evaluating different breeds for vari ous purposes. It's the kind of book would-be dog owners should be required to read before even contemplating buying a dog.” —The Washington Post Book World “Excellent book . Many of us want to think our dog’s persona is characterized by an austere veneer, a streak of intelligence, and a fearless-go-for-broke posture. No matter wrhat your breed, The In telligence of Dogs . will tweak your fierce, partisan spirit . Coren doesn’t stop at intelligence and obedience rankings, he also explores breeds best suited as watchdogs and guard dogs . [and] does a masterful job of exploring his subject's origins, vari ous forms of intelligence gleaned from genetics and owner/trainer conditioning, and painting an inner portrait of the species.” —The Seattle Times "This book offers more than its w7ell-publicized ranking of pure bred dogs by obedience and working intelligence. -

Brian Hare’S Deutscher Platz

PERSONAL PORTRAIT EVOLUTIONARY ANTHROPOLOGY Brian BrianHare Hare he clipping from the German ing that fits in well at its location on The Max Planck researcher began Tnewspaper BILD on Brian Hare’s Deutscher Platz. Inside, life is inter- studying at the psychology depart- office door is a real eye-catcher. It national; it is the Max Planck Insti- ment of Emory University in Atlanta shows a photograph of the Ameri- tute with the largest percentage of and was thrilled. There were “cool can researcher with a fox, with a researchers from abroad. The five di- lectures” in psychology and anthro- short text below – “full of mis- rectors alone come from five differ- pology, and the student whose high takes,” as Hare comments. What was ent countries. No one really notices school grades were “not particularly a serious scientist like Hare doing in that Brian Hare speaks only a little outstanding” now garnered only the Germany’s most popular daily German. best marks. At Emory he met his tabloid? The article’s headline re- most important teacher: Michael PRACTICAL TRAINING IN THE veals the reason: “Foxes are the bet- (“Mike”) Tomasello, professor of psy- ECUADORIAN JUNGLE ter dogs,” it says. Brian Hare, born chology. Tomasello is one of the in 1976, investigates the social be- Hare was at the institute earlier, from founding Directors of the institute in havior of dogs, and man’s best 2001 to 2002, to collect data for his Leipzig and, as Director of the De- friend is always a good topic for a Ph.D. In 2004, he returned to Leipzig partment for Developmental Psy- wide audience. -

Train Your Dog to Be Well Members Who Have Just Returned

ave you ever met a dog who H always jumps up and tries to lick your face when she Doctor dog? greets you or your friends? You might think it is cute if it is your dog and Dogs are being trained to use their you know she is friendly. But most sense of smell to find cancers in humans Step 3: others find this behaviour annoying, that may be too small to Hand Signals Dogs will also perform commands with hand especially if she has muddy paws be spotted by doctors. Why do dogs jump signals. In this case, the signal you want to up? and she leaves two streaks of mud They can even find u Dogs must think down the length of a white shirt. It is lung cancer by sniffing se for sitting is to have both hands flat, palms up, facing the dog (see photo). At the people are weird also just plain scary when a dog a person’s breath.* same because we don’t charges toward you and leaps up at time like the normal your face. you say canine greeting “sit,” use behaviour. Dogs Most people put their hands up to signal. Once she gets usedthis new to seeing hand greet each protect themselves (see photo) as a the hand signal with the association of other by sniff- natural reaction. You can use this the sit command, try just the hand ing and lick- response to train your dog to be well signal. Be patient. Give the hand signal ing the mannered and not jump. -

Canine Istener Spring 2020

THE ANINE ISTENER CDogs for Better Lives Spring 2020 • NO.136 L MagazinMagazine Philly & Laurrie A Traveling Team Community Makes It Possible Celebrating Our Partnerships 100% Funding Model Fueling DBL’s Long-term Viability FEATURES 9 12 10 13 Spring 2020 | No. 136 100% Funding Wellie Assists Philly and Laurrie: A Model Others in Need Traveling Team 10 9 13 DBL’s Guadian Society Jennifer and Hearing Hearing Assistance Dog members are fueling Assistance Dog Wellie Philly and Laurrie are DBL’s long-term viability. provide help to others enjoying life together in in need. Hawaii. DBL is Going Solar 12 Dogs for Better Lives has received a Blue Sky 2020 funding award from Pacific Power. in partnership with Sunthurst Energy, DBL will soon begin the installation of a 97 kW solar array. SPRING 2020 1-800-990-3647 Page 2 THE CANINEL ISTENER ALSO 4 CEO Letter 5 We Get Letters 6 Placement Highlights 8 Follow Ups 10 100% Funding Model 11 DBL’s Seattle Office Launch 12 Reducing DBL’s Carbon Pawprint 13 Laurrie & Philly 11 18 Community Makes it Possible 20 RAD Alliance Partners 21 Staff Spotlight: Grace Mitchell 23 Puppy Graduation 24 Client’s Corner: Q&A with Andrea Bus On the Cover The front and back cover photos feature Dogs for Better Lives’ client Laurrie and her Hearing Assistance Dog 23 Philly. Photos taken in Maui, Hawaii by Leslie Turner, Leslie Turner Photography. Canine Listener Team Managing Editor — Monica Schuster Contributing Editors — Emily Minah, Mary Rosebrook 18 Designed by Laurel Briggs, Creative Marketing Design, Jacksonville, Oregon Printed by Consolidated Press, Seattle, Washington Special thanks to all contributing writers, photographers and clients who supported this spring issue! 21 24 dogsforbetterlives.org SPRING 2020 THE CANINEL ISTENER Page 3 PRESIDENT & CEO LETTER FROM BRYAN WILLIAMS “Here’s to the crazy ones. -

ASPCA Adopt a Rescued Bird Month National Train Your Dog

ASPCA Adopt A Rescued Bird Month Pet Holidays 2015 National Train Your Dog Month National Walk Your Pet Month JANUARY 1: New Year’s Day JANUARY 2: Happy Mew Year for Cats Day JANUARY 2: National Pet Travel Safety Day JANUARY 5: National Bird Day JANUARY 14: National Dress Up Your Pet Day JANUARY 19: Martin Luther King Day JANUARY 24: Change a Pet’s Life Day JANUARY 29: Seeing Eye Guide Dog Birthday January ASPCA Adopt A Rescued Rabbit Month Dog Training Education Month Humane Society of the United States Spay/Neuter Awareness Month National Cat Health Month National Pet Dental Health Month National Prevent a Litter Month Responsible Pet Owners Month Unchain a Dog Month FEBRUARY 1: Animal Planet’s Puppy Bowl XI FEBRUARY 1: Hallmark Channel’s Kitten Bowl II FEBRUARY 2: Groundhog Day FEBRUARY 2: Hedgehog Day FEBRUARY 3: St. Blaise Day (Patron saint of veterinarians and animals) FEBRUARY 7-14: Have a Heart for a Chained Dog Week Pet Holidays 2015 FEBRUARY 14: Valentine’s Day FEBRUARY 14: National Pet Theft Awareness Day FEBRUARY 15-21: National Justice for Animals Week FEBRUARY 16-17: Westminster Kennel Club Annual Dog Show FEBRUARY 16: President’s Day FEBRUARY 19: Chinese New Year FEBRUARY 20: Love Your Pet Day FEBRUARY 22: Walking the Dog Day FEBRUARY 23: International Dog Biscuit Appreciation Day FEBRUARY 24: World Spay Day / Spay Day USA February ASPCA Adopt A Rescued Guinea Pig Month Poison Prevention Awareness Month MARCH 1: National Horse Protection Day Pet Holidays 2015 MARCH 1-7: Professional Pet Sitters Week MARCH 5-8: Crufts (The World’s Largest Dog Show) held in Birmingham, England MARCH 7: Iditarod Race Starts (Awards Banquet on March 22) MARCH 8: Daylight Savings Time Starts MARCH 13: K-9 Veterans Day MARCH 15-21: Poison Prevention Week MARCH 17: St. -

2021 AKC Trick Dog AKC Canine Good Citizen Rules for Ohio 4-H

OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION 2021 AKC Trick Dog and AKC Canine Good Citizen Rules for Ohio 4-H/Ohio State Fair Participation CFAES provides research and related educational programs to clientele on a non-discriminatory basis. For more information, visit cfaesdiversity.osu.edu. For an accessible format of this publication, visit cfaes.osu.edu/accessibility. AKC Trick Dog and AKC Canine Good Citizen Rules for Ohio 4-H/Ohio State Fair Participation Table of Contents County-Use of Ohio 4-H/OSF Dog Rules and Regulations…………………………………………………………………………. 4 2021 General Dog Show Rules for Ohio 4-H/Ohio State Fair Participation Preface………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Project Eligibility………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 5 Dog Eligibility………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Ownership Requirements……………………………………………………………………………………………………. 6 Definitions of Ownership…………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 6 Training……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Showing………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 7 Safety and Sportsmanship…………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Permission to Participate in Ohio 4-H Dog Activities Disclosure and Release of Claims……………………………. 8 Misbehavior and Excusals for Dogs on the Fairgrounds, Show Area, or in the Show Ring…………………………. 8 Unsportsmanlike Conduct………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Other…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 9 License Requirements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 9 Health Requirements…………………………………………………………………………………………………………… -

Are You Ready for Parenthood?

05_779628 ch01.qxp 5/9/06 2:27 PM Page 1 1 Are You Ready for Parenthood? hen you acquire your very own dog or puppy, it is like having a baby in the house. Only you are now the parent! The family dog Wmay have been your sibling, but with your own dog, you are now the person of authority and the person responsible for someone else. Pet ownership means that you may sometimes have to give up your own fun activities in order to care for your dog properly—just like your parents need to sacrifice for you sometimes. Still, having a dog has so many rewards of its own that you will probably not even notice. Why Dogs Are Good for Kids Dogs are good for you for many reasons. A dog is a friend who will always be there for you, 24/7. Your dog is never too busy to hang out with you and is always willing to try anything you want—be it a midnight snack or an early morning COPYRIGHTEDjog in the park. A dog will sleep MATERIAL in with you or get up early with no complaints. A dog provides unconditional love, even when you are having a bad day or are in a bad mood. A dog won’t care if your hair is a mess, you flunked your math test, or you were dead last in the cross-country meet. Your dog won’t even care if you snore at night; he probably snores too! 1 05_779628 ch01.qxp 5/9/06 2:27 PM Page 2 2 Head of the Class Kids and dogs keep each other in great shape. -

TRANSCENDENT WASTE by Robert Dale Glick a Dissertation Submitted

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by The University of Utah: J. Willard Marriott Digital Library TRANSCENDENT WASTE by Robert Dale Glick A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English The University of Utah August 2012 Copyright © Robert Dale Glick 2012 All Rights Reserved The University of Utah Graduate School STATEMENT OF DISSERTATION APPROVAL The dissertation of Robert Dale Glick has been approved by the following supervisory committee members: Lance Olsen , Chair 4/19/2012 Date Approved Melanie Rae Thon , Member 4/19/2012 Date Approved Scott Black , Member 4/19/2012 Date Approved Kathryn Bond Stockton , Member 4/19/2012 Date Approved Lisa Henry Benham , Member 4/19/2012 Date Approved and by Vince Pecora , Chair of the Department of English and by Charles A. Wight, Dean of The Graduate School. ABSTRACT Transcendent Waste is a collection of stories that explores the difficulties of bereavement through what we literally and metaphorically throw away. Characters in Transcendent Waste question the validity of ritual in healing, displace guilt and grief onto relationship and career, and attempt to empathize with others who understand death and mourning in radically different ways. Influenced by Bataillean notions of excess and Kristeva’s concept of the abject, I explore loss by using the concept of “waste” within literal, symbolic, and conceptual frameworks. Waste can signify trash, a surfeit of language, the lost potential of a life, the misuse of time, or the degradation of the body.