Paying NCAA Athletes David J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPORTS Wiggins Leads Wolves Past Heat 116-109 with Late 3 Barrage When He Has to Kick It Up,” Towns Said

theconcordian.org • October 31, 2019 THE CONCORDIAN 6 SPORTS Wiggins leads Wolves past Heat 116-109 with late 3 barrage when he has to kick it up,” Towns said. stretch, I’m going to give it my all to start a season, Towns went 2 for 11 from BY DAVE CAMPBELL “For some reason, he always hits those make a play,” Wiggins said. the field after the first quarter. ... The AP SPORTS WRITER shots at the end when we need him the After started the season 0 for 13 from Wolves have won four straight home most.” long range, Wiggins had a well-timed openers. MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — Andrew Kendrick Nunn had 25 points on first make with 5:52 left to tie the game NUNN BETTER Wiggins has been the face of unfulfilled 5-for-9 shooting from 3-point range, at 96. He gave the Wolves the lead for Nunn, one of four rookies on a Heat potential for the Minnesota Timber- Duncan Robinson pitched in with 21 good with 2:56 left, the first of three roster that’s half-filled with under-25 wolves, beginning his sixth NBA season points, and Justise Winslow scored 20 3-pointers he hit in as many posses- players, has been quite the fill-in for and starting the second year of his $147 for the Heat, who played again without sions. With 1:45 remaining, he simply Butler on the wing over his first three million maximum contract. new star Jimmy Butler and took their dribbled back and forth on the left wing NBA games. -

Jazz Three-Point Barrage Beats Hornets

Established 1961 Sport WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 24, 2021 Jazz three-point barrage beats Hornets Wizards beat Lakers in OT • Mavs, Suns win LOS ANGELES: Donovan Mitchell had 23 points and eight assists as the NBA-leading Utah Jazz rained a franchise-record 28 three-pointers in a 132-110 rout of the Charlotte Hornets on Monday. Joe Ingles and Georges Niang scored 21 points apiece as the Jazz got a superb offensive performance from their bench to win for the 21st time in their last 23 games and improve to 25-6 overall. Jordan Clarkson (five threes), Mike Conley (four threes), Mitchell (three threes) and Royce O’Neale (two threes) contributed to the Jazz’s domination from beyond the arc. Conley also had 15 points. Gordon Hayward scored 21 points but had to leave the game in the fourth quarter with a hand injury as the Hornets’ six-game road trip got off to a rocky start. Rookie LaMelo Ball also scored 21 points as the Hornets kept it close until the fourth quarter when the Jazz seized command. In Texas, Tim Hardaway scored a team-high 29 points as the Dallas Mavericks delivered one of their best defensive games of the season, by limiting the Memphis Grizzlies to just 39 percent shooting on Monday. Luka Doncic scored 21 points and Jalen Brunson chipped in 19 as the Mavericks returned from an unexpected eight-day break to post a 103-92 victo- ry at the American Airlines Center. The Mavericks had not played since February 14 after a devastating winter storm wreaked havoc on the Dallas area and forced two postponements. -

PAT DELANY Assistant Coach

ORLANDO MAGIC MEDIA TOOLS The Magic’s communications department have a few online and social media tools to assist you in your coverage: *@MAGIC_PR ON TWITTER: Please follow @Magic_PR, which will have news, stats, in-game notes, injury updates, press releases and more about the Orlando Magic. *@MAGIC_MEDIAINFO ON TWITTER (MEDIA ONLY-protected): Please follow @ Magic_MediaInfo, which is media only and protected. This is strictly used for updated schedules and media availability times. Orlando Magic on-site communications contacts: Joel Glass Chief Communications Officer (407) 491-4826 (cell) [email protected] Owen Sanborn Communications (602) 505-4432 (cell) [email protected] About the Orlando Magic Orlando’s NBA franchise since 1989, the Magic’s mission is to be world champions on and off the court, delivering legendary moments every step of the way. Under the DeVos family’s ownership, the Magic have seen great success in a relatively short history, winning six division championships (1995, 1996, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2019) with seven 50-plus win seasons and capturing the Eastern Conference title in 1995 and 2009. Off the court, on an annual basis, the Orlando Magic gives more than $2 million to the local community by way of sponsorships of events, donated tickets, autographed merchandise and grants. Orlando Magic community relations programs impact an estimated 100,000 kids each year, while a Magic staff-wide initiative provides more than 7,000 volunteer hours annually. In addition, the Orlando Magic Youth Foundation (OMYF) which serves at-risk youth, has distributed more than $24 million to local nonprofit community organizations over the last 29 years.The Magic’s other entities include the team’s NBA G League affiliate, the Lakeland Magic, which began play in the 2017-18 season in nearby Lakeland, Fla.; the Orlando Solar Bears of the ECHL, which serves as the affiliate to the NHL’s Tampa Bay Lightning; and Magic Gaming is competing in the second season of the NBA 2K League. -

2017 Hoop Summit Media Guide

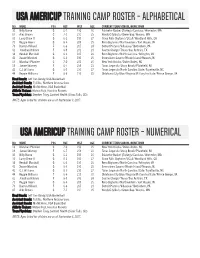

usa Americup training camp roster - alphabetical NO NAME POS HGT WGT AGE CURRENT TEAM/SCHOOL/HOMETOWN 30 Billy Baron G 6-2 195 26 Eskisehir Basket (Turkey)/Canisius/Worcester, MA 87 Alec Brown C 7-1 231 25 Windy City Bulls/Green Bay/Winona, MN 31 Larry Drew II G 6-2 180 27 Sioux Falls Skyforce/UCLA/Woodland Hills, CA 71 Reggie Hearn G 6-4 209 25 Reno Bighorns/Northwestern/Fort Wayne, IN 73 Darrun Hilliard F 6-6 205 24 Detroit Pistons/Villanova/ Bethlehem, PA 62 Jonathan Holmes F 6-9 242 24 Canton Charge/Texas/San Antonio, TX 34 Kendall Marshall G 6-4 195 26 Reno Bighorns/North Carolina/Arlington, VA 41 Xavier Munford G 6-3 190 25 Greensboro Swarm/Rhode Island/Newark, NJ 18 Marshall Plumlee C 7-0 250 25 New York Knicks/Duke/Arden, NC 19 Jameel Warney F 6-7 259 23 Texas Legends/Stony Brook/Plainfield, NJ 42 C.J. Williams G 6-5 230 27 Texas Legends/North Carolina State/Fayetteville, NC 44 Reggie Williams F 6-6 210 30 Oklahoma City Blue/Virginia Military Institute/Prince George, VA Head Coach: Jeff Van Gundy, USA Basketball Assistant Coach: Ty Ellis, Northern Arizona Suns Assistant Coach: Mo McHone, USA Basketball Athletic Trainer: Motoki Fujii, Houston Rockets Team Physician: Stephen Foley, Sanford Health (Sioux Falls, SD) NOTE: Ages listed for athletes are as of September 3, 2017. usa Americup training camp roster - NUMERIcal NO NAME POS HGT WGT AGE CURRENT TEAM/SCHOOL/HOMETOWN 18 Marshall Plumlee C 7-0 250 25 New York Knicks/Duke/Arden, NC 19 Jameel Warney F 6-7 259 23 Texas Legends/Stony Brook/Plainfield, NJ 30 Billy Baron G 6-2 195 26 Eskisehir Basket (Turkey)/Canisius/Worcester, MA 31 Larry Drew II G 6-2 180 27 Sioux Falls Skyforce/UCLA/Woodland Hills, CA 34 Kendall Marshall G 6-4 195 26 Reno Bighorns/North Carolina/Arlington, VA 41 Xavier Munford G 6-3 190 25 Greensboro Swarm/Rhode Island/Newark, NJ 42 C.J. -

Basketballbasketball Guide to the Games

POST’S GUIDE to the PAN AM GAMES BASKETBALLBasketball GUIDE TO THE GAMES B Y ERIC KOR ee N , NATIONAL POST Venue Ryerson Athletic Centre, which you may know by another name. Venue acronym RYA Landmark status High In a prior life, this venue was known as Maple Leaf Gardens, the home of the National Hockey League’s Maple Leafs from 1931- 99. It was dormant for years after until Loblaw Companies bought the facility in 2004, entering into a joint-use agreement with Ryer- son University in 2011. Now, the building is split between Ryer- son — the school’s gym and ice 2 NATIONAL POST GUIDE TO THE GAMES rink are there, and the top-floor arena recently held the CIS Final 8 in men’s basketball — and a Loblaws store at street level. If you get hungry in the middle of some games, there is a dynamite prepared-food section. At their prices, you will only save a bit on concessions, though. Other events at venue Wheelchair basketball, at the Parapan Am Games. Transit options Take Line 1 of the TTC’s subway system to College Station, and enjoy a two-minute walk east on Carlton Street to the facility. For exact directions, try: Triplinx.ca 3 NATIONAL POST GUIDE TO THE GAMES TTC trip planner Schedule Women Men Round robin July 16-18 July 21-23 Semifinals July 19 July 24 Final July 20 July 25 See the full competition schedule at the Pan Am website How it works At the opposite ends of a 94-foot parquet floor, there are two hoops, 10 feet off of the … actual- ly, we are going to assume you have seen basketball before. -

MBKB Week 08.Indd

MEN’S BASKETBALLDecember 31, 2015 SCHOLARS | CHAMPIONS | LEADERS SEC COMMUNICATIONS Conference Overall Craig Pinkerton (Men’s Basketball Contact) W-L Pct. H A W-L Pct. H A N Strk [email protected] @SEC_Craig www.SECsports.com South Carolina 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 12-0 1.000 8-0 1-0 3-0 W12 Phone: (205) 458-3000 Kentucky 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 10-2 .833 8-0 0-1 2-1 W1 Ole Miss 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 10-2 .833 5-0 4-0 1-2 W7 THIS WEEK IN THE SEC Texas A&M 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 10-2 .833 8-0 0-1 2-1 W3 (All Times Eastern) Alabama 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 8-3 .727 4-1 2-1 2-1 W1 December 23 (Wednesday) Florida 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 9-4 .692 6-1 1-2 2-1 L1 Diamond Head Classic (Honolulu, HI) Georgia 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 6-3 .667 6-2 0-1 0-0 W3 Harvard 69, Auburn 51 Vanderbilt 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 8-4 667 6-1 0-2 2-1 W1 Illinois 68, Missouri 63 Mississippi State 93, Northern Colo. 69 LSU 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 7-5 .583 7-1 0-2 0-2 L1 Tennessee 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 7-5 .583 7-0 0-2 0-3 W2 December 25 (Friday) Auburn 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 6-5 .545 4-1 1-3 1-1 L2 Diamond Head Classic (Honolulu, HI) at Hawaii 79, Auburn 67 Mississippi State 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 6-5 .545 4-1 0-2 2-2 W2 Arkansas 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 6-6 .500 6-2 0-2 0-2 L1 December 26 (Saturday) Missouri 0-0 .000 0-0 0-0 6-6 .500 6-1 0-2 0-3 W1 at #12 Kentucky 75, #15 Louisville 73 December 29 (Tuesday) • SEC Player of the Week – Kentucky’s Tyler a season. -

2014-15 NABC-Division I ALL-DISTRICT TEAMS and Coaches

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Rick Leddy, NABC 203-239-4253 ([email protected]) National Association of Basketball Coaches Announces 2014-15 Division I All-District Teams and UPS All-District Coaches KANSAS CITY, Mo. (March 27, 2015) -- The National Association of Basketball Coaches (NABC) announced today the NABC Division I All-District teams and UPS All-District coaches for 2014-15. Selected and voted on by member coaches of the NABC, these student-athletes and coaches represent the finest basketball players and coaches across America. 2014-15 NABC DIVISION I ALL-DISTRICT TEAMS District 1 District 3 First Team First Team David Laury Iona John Brown High Point A.J. English Iona Saah Nimley Charleston Southern Emmy Andujar Manhattan Keon Moore Winthrop Jameel Warney Stony Brook Brett Comer Florida Gulf Coast Zaid Hearst Quinnipiac Ty Greene USC Upstate Second Team Second Team Sam Rowley Albany Javonte Green Radford Matt Lopez Rider Jerome Hill Gardner Webb Ousmane Drame Quinnipiac Warren Gillis Coastal Carolina Chavaughn Lewis Marist Dallas Moore North Florida Justin Robinson Monmouth Bernard Thompson Florida Gulf Coast District 2 District 4 First Team First Team Jahlil Okafor Duke Treveon Graham VCU Jerian Grant Notre Dame DeAndre’ Bembry Saint Joseph’s Rakeem Christmas Syracuse Jordan Sibert Dayton Malcolm Brogdon Virginia Kendall Anthony Richmond Justin Anderson Virginia E.C. Matthews Rhode Island Second Team Second Team Terry Rozier Louisville Jordan Price La Salle Montrezl Harrell Louisville Tyler Kalinoski Davidson Quinn Cook Duke Dyshawn Pierre Dayton Marcus Paige North Carolina PatricioOlivier Hanlan Garino BostonGeorge College Washington Olivier Hanlan Boston College Hassan Martin Rhode Island District 5 District 8 First Team First Team Darrun Hilliard Villanova Buddy Hield Oklahoma Kris Dunn Providence Georges Niang Iowa State LaDontae Henton Providence Perry Ellis Kansas D’Angelo Harrison St. -

Card Set # Player Team Seq. Acetate Rookies 1 Tyrese Maxey

Card Set # Player Team Seq. Acetate Rookies 1 Tyrese Maxey Philadelphia 76ers Acetate Rookies 2 RJ Hampton Denver Nuggets Acetate Rookies 3 Obi Toppin New York Knicks Acetate Rookies 4 Anthony Edwards Minnesota Timberwolves Acetate Rookies 5 Deni Avdija Washington Wizards Acetate Rookies 6 LaMelo Ball Charlotte Hornets Acetate Rookies 7 James Wiseman Golden State Warriors Acetate Rookies 8 Cole Anthony Orlando Magic Acetate Rookies 9 Tyrese Haliburton Sacramento Kings Acetate Rookies 10 Jalen Smith Phoenix Suns Acetate Rookies 11 Patrick Williams Chicago Bulls Acetate Rookies 12 Isaac Okoro Cleveland Cavaliers Acetate Rookies 13 Kira Lewis Jr. New Orleans Pelicans Acetate Rookies 14 Aaron Nesmith Boston Celtics Acetate Rookies 15 Killian Hayes Detroit Pistons Acetate Rookies 16 Onyeka Okongwu Atlanta Hawks Acetate Rookies 17 Josh Green Dallas Mavericks Acetate Rookies 18 Precious Achiuwa Miami Heat Acetate Rookies 19 Saddiq Bey Detroit Pistons Acetate Rookies 20 Zeke Nnaji Denver Nuggets Acetate Rookies 21 Aleksej Pokusevski Oklahoma City Thunder Acetate Rookies 22 Udoka Azubuike Utah Jazz Acetate Rookies 23 Isaiah Stewart Detroit Pistons Acetate Rookies 24 Devin Vassell San Antonio Spurs Acetate Rookies 25 Immanuel Quickley New York Knicks Art Nouveau 1 Anthony Edwards Minnesota Timberwolves Art Nouveau 2 James Wiseman Golden State Warriors Art Nouveau 3 LaMelo Ball Charlotte Hornets Art Nouveau 4 Patrick Williams Chicago Bulls Art Nouveau 5 Isaac Okoro Cleveland Cavaliers Art Nouveau 6 Onyeka Okongwu Atlanta Hawks Art Nouveau 7 Killian Hayes Detroit Pistons Art Nouveau 8 Obi Toppin New York Knicks Art Nouveau 9 Deni Avdija Washington Wizards Art Nouveau 10 Devin Vassell San Antonio Spurs Art Nouveau 11 Tyrese Haliburton Sacramento Kings Art Nouveau 12 Jalen Smith Phoenix Suns Art Nouveau 13 Cole Anthony Orlando Magic Art Nouveau 14 Aaron Nesmith Boston Celtics Art Nouveau 15 Kira Lewis Jr. -

Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 Vs

CUSE.COM Christmas’ Season and Career Highs Points Season: 35 vs. Wake Forest Career: 35 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 FG Made S Y R A C U E Season: 13 vs. Wake Forest Career: 13 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 25 FG Attempted Season: 21 vs. Wake Forest Rakeem Christmas Career: 21 vs. Wake Forest, 2014-15 O R A N G E Senior 6-9 250 3-Point FGM Philadelphia, Pa. Season: 0 Career: 0 Academy of the New Church 3-Point FGA Season: 1 at North Carolina NEW YORK’S COLLEGE TEAM Career: 1 at North Carolina, 2014-15 FT Made Ranks third in the ACC in scoring (17.5 ppg.), fourth in rebounding (9.1), fi fth in fi eld goal Season: 11 vs. Louisville percentage (.552), second in blocked shots (2.52), sixth in off ensive rebounds (3.13) and Career: 11 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 FT Attempted fi fth defensive rebounds (5.97). Season: 13 vs. Louisville Nominated for the 2015 Allstate NABC and WBCA Good Works Teams. Career: 13 vs. Louisville, 2014-15 Finalist for the Wooden Award. Rebounds Season: 16 vs. Hampton Finalist for the Kareem Abdul-Jabbar Award. Career: 16 vs. Hampton, 2014-15 Finalist for the Robertson Trophy. Off. Rebounds Named to Lute Olson Award Watch List. Season: 6 vs. Kennesaw State, Hampton, St. John’s, Long Beach State, at Duke Named to Naismith Award Midseason Top 30. Career: 8 vs. Boston College, 2013-14 Earned ACSMA Most Improved Player Award and was named to ACSMA All-ACC First Team Def. -

Official Basketball Box Score -- Game Totals -- Final Statistics Wofford Vs Duke 12/31/14 3:04 P.M. at Cameron Indoor Stadium (Durham, N.C.)

Official Basketball Box Score -- Game Totals -- Final Statistics Wofford vs Duke 12/31/14 3:04 p.m. at Cameron Indoor Stadium (Durham, N.C.) Wofford 55 • 9-4 Total 3-Ptr Rebounds ## Player FG-FGA FG-FGA FT-FTA Off Def Tot PF TP A TO Blk Stl Min 24 Justin Gordon f 3-6 0-0 3-4 2 2 4 2 9 0 3 0 2 22 34 Lee Skinner f 3-10 0-1 0-0 1 2 3 4 6 1 1 0 1 29 02 Karl Cochran g 5-17 3-9 0-0 1 4 5 3 13 2 2 0 0 32 05 Eric Garcia g 3-4 1-1 1-2 0 0 0 1 8 3 0 0 0 27 14 Spencer Collins g 0-5 0-3 4-4 2 3 5 2 4 1 1 0 0 26 01 Derrick Brooks 1-2 0-0 0-1 0 3 3 0 2 0 1 1 0 13 03 John Swinton 0-0 0-0 0-0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 20 Jaylen Allen 3-6 1-3 0-0 1 2 3 2 7 1 2 0 0 24 31 C.J. Neumann 1-3 0-0 0-0 3 1 4 3 2 1 2 0 0 19 33 Cameron Jackson 2-2 0-0 0-0 0 2 2 3 4 0 1 0 1 7 Team 0 0 0 Totals 21-55 5-17 8-11 10 19 29 21 55 9 13 1 4 200 FG % 1st Half: 11-28 39.3% 2nd half: 10-27 37.0% Game: 21-55 38.2% Deadball 3FG % 1st Half: 4-7 57.1% 2nd half: 1-10 10.0% Game: 5-17 29.4% Rebounds FT % 1st Half: 8-11 72.7% 2nd half: 0-0 0.0% Game: 8-11 72.7% 0,1 Duke 84 • 12-0 Total 3-Ptr Rebounds ## Player FG-FGA FG-FGA FT-FTA Off Def Tot PF TP A TO Blk Stl Min 12 Justise Winslow f 5-11 2-4 4-4 2 5 7 0 16 2 1 0 1 31 21 Amile Jefferson f 3-6 0-0 4-6 3 2 5 3 10 0 1 0 0 18 15 Jahlil Okafor c 11-13 0-0 2-5 1 7 8 1 24 1 2 2 2 32 02 Quinn Cook g 5-8 3-6 2-2 0 1 1 1 15 2 0 0 1 35 05 Tyus Jones g 2-4 1-2 0-0 0 6 6 3 5 5 2 0 4 32 03 Grayson Allen 1-1 1-1 0-0 0 0 0 0 3 0 0 0 0 4 13 Matt Jones 0-4 0-1 2-2 0 2 2 3 2 1 0 0 2 18 14 Rasheed Sulaimon 2-4 1-2 1-2 0 2 2 3 6 2 2 0 0 19 40 Marshall Plumlee 0-1 0-0 3-4 1 2 3 0 3 0 0 0 0 11 Team 0 0 0 Totals 29-52 8-16 18-25 7 27 34 14 84 13 8 2 10 200 FG % 1st Half: 12-28 42.9% 2nd half: 17-24 70.8% Game: 29-52 55.8% Deadball 3FG % 1st Half: 3-8 37.5% 2nd half: 5-8 62.5% Game: 8-16 50.0% Rebounds FT % 1st Half: 14-19 73.7% 2nd half: 4-6 66.7% Game: 18-25 72.0% 3 Officials: Raymond Styons, Earl Walton, Tim Comer Technical fouls: Wofford-None. -

National Basketball Association

NATIONAL BASKETBALL ASSOCIATION OFFICIAL SCORER'S REPORT FINAL BOX Wednesday, October 25, 2017 Chesapeake Energy Arena, Oklahoma City, OK Officials: #45 Brian Forte, #11 Derrick Collins, #12 CJ Washington Game Duration: 2:18 Attendance: 18203 (Sellout) VISITOR: Indiana Pacers (2-3) POS MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS +/- PTS 44 Bojan Bogdanovic F 28:51 0 7 0 5 4 4 0 2 2 2 2 1 5 0 -19 4 21 Thaddeus Young F 33:29 5 12 3 6 1 2 1 3 4 0 2 2 2 0 -15 14 11 Domantas Sabonis C 18:44 1 9 0 0 2 2 8 3 11 2 5 0 1 0 -11 4 4 Victor Oladipo G 35:50 11 18 5 8 8 8 0 5 5 0 5 1 3 2 -20 35 2 Darren Collison G 37:49 5 12 2 4 6 6 0 2 2 3 2 2 4 0 -13 18 25 Al Jefferson 18:11 1 4 0 0 3 3 1 6 7 2 2 2 3 0 -3 5 1 Lance Stephenson 17:05 2 7 0 2 1 3 0 4 4 1 2 1 0 0 4 5 22 TJ Leaf 19:22 1 4 0 1 0 1 1 2 3 1 1 1 0 0 -4 2 6 Cory Joseph 21:11 1 6 0 2 4 4 1 0 1 2 2 2 0 0 -5 6 0 Alex Poythress 02:22 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 -1 0 3 Joe Young 02:22 1 2 0 0 1 2 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 -1 3 12 Damien Wilkins 02:22 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 -1 0 13 Ike Anigbogu 02:22 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 -1 0 240:00 28 83 10 29 30 35 14 27 41 13 23 13 19 2 -18 96 33.7% 34.5% 85.7% TM REB: 10 TOT TO: 19 (12 PTS) HOME: OKLAHOMA CITY THUNDER (2-2) POS MIN FG FGA 3P 3PA FT FTA OR DR TOT A PF ST TO BS +/- PTS 13 Paul George F 19:06 4 8 0 3 2 3 0 1 1 0 6 0 1 1 -2 10 7 Carmelo Anthony F 32:59 9 17 3 7 7 9 0 10 10 1 3 0 6 3 19 28 12 Steven Adams C 30:51 8 13 0 0 1 1 7 4 11 1 1 2 3 2 16 17 21 Andre Roberson G 20:40 2 5 0 1 0 0 2 0 2 1 3 0 1 1 11 4 0 Russell Westbrook G 35:09 10 18 -

Pick Team Player Drafted Height Weight Position

PICK TEAM PLAYER DRAFTED HEIGHT WEIGHT POSITION SCHOOL/RE STATUS PROS CONS NBA Ceiling NBA Floor Comparison GION Comparison 1 Boston Celtics (via Nets) Markelle Fultz 6'4" 190 PG Washington Freshman High upside, immediate No significant flaws John Wall Jamal Crawford NBA production 2 Los Angeles Lakers Lonzo Ball 6"6 190 PG/SG UCLA Freshman High college production Slight lack of athleticism Kyrie Irving Jrue Holiday 3 Phoenix Suns Josh Jackson 6"8" 205 SG/SF Kansas Freshman High defensive potential Shot creation off the dribble Kawhi Leonard Michael Kidd Gilchrist 4 Orlando Magic Jonathan Isaac 6'10" 210 SF/PF Florida State Freshman High defensive potential, 3 Very skinny frame Paul George Otto Porter point shooting 5 Philadephia 76ers Malik Monk 6'3" 200 SG Kentucky Freshman High college production Slight lack of height CJ MCCollum Lou Williams 6 Sacramento Kings Dennis Smith 6'2" 195 PG NC State Freshman High athleticism 3 point shooting Russell Westbrook Eric Bledsoe 7 New York Knicks Lauri Markkanen 7'1" 230 PF Arizona Freshman High production, 3 point Low strength Kristaps Porzingiz Channing Frye shooting 8 Sacramento Kings (via Jayson Tatum 6'8" 205 SF Duke Freshman High NBA floor, smooth Lack of intesity Harrison Barnes Trevor Ariza Pelicans) offense 9 Minnesota Frank Ntilikina 6'5' 190 PG France International High upside 3 point shooting George Hill Michael Carter Williams Timberwolves 10 Dallas Mavericks Terrance Ferguson 6'7" 185 SG/SF USA International High upside Poor ball handling Klay Thompson Tim Hardaway JR 11 Charlotte