BOYCE PARK Prepared for the Allegheny County Parks Foundation January, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sharing a Special Bond by Gail Scott Ay 21St Is a Special Day in the Life of the Lynn and Daugherty Families

The Hampton News June 2020 From the Neighborhoods of Hampton Township, PA Vol. 15 No. 11 Sharing A Special Bond by Gail Scott ay 21st is a special day in the life of the Lynn and Daugherty families. It was one year ago, M on May 21, 2019, that Bill Daugherty donated a kidney to Dale Lynn, and, interestingly, both men are from Hampton. In the summer of 2018, Dale became very sick and lost over 35lbs. After a hospital stay, it was determined that his kidney and pancreas were not functioning properly. Dale had been born with only one kidney and now, it was operating at 5%. He started dialysis in January and was Photo by Madia Photography added to the National Transplant List. At that time there (Continued on page 17) Dale Lynn and Bill Daugherty after the surgery, then one year later Cap, Gown, Mask Taking Care of Their Friends Like us on Facebook by June Gravitte by Gail Scott Follow us on Twitter This year, Hampton High School sen- Face masks have become a hot commodity ior Katelyn Januck’s artwork was selected recently because of safety measures for Covid- What’s Inside to represent her class as a part of the per- 19. Two local Hampton women have been busy Message from Township Mgr. .... 3 manent art collection that is displayed sewing face masks and they are helping to keep Police Log .................................... 4 outside of the high school library. What their friends and neighbors safe. Real Estate ................................... 7 makes this year’s piece unique is the fact Marcia Rhea has sewn over 900 masks to Library ..................................... -

N N E W S L E T T E

WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA MUSHROOM CLUB n NEWSLETTERn Volume 16, Issue 2 MAY / JUNE 2016 16th Annual Lincoff Foray: President’s Message Saturday, September 24, 2016 RICHARD JACOB THE 16TH ANNUAL Gary Lincoff Foray will be held at The WPMC President Rose Barn in Allegheny County’s North Park. This year’s program will be a single-day event featuring Gary I HAVE BEEN WATCHING THE Lincoff, author of the Audubon Guide to Mushrooms of North MorelHunters.com sightings map, in America, The Complete Mushroom Hunter, The Joy of Forag- anticipation of the first of this sea- ing, and many others. This year we are delighted to have as son’s morels. The first morel sighting our Guest Mycologist Dr. Nicholas Money, author of Mush- in our area at the end of March was rooms, The Triumph of the Fungi and Mr. Bloomfield’s Orchard: not on the MorelHunters website but The Mysterious World of Mushrooms, Molds and Mycologists. on our Facebook Group page, reported by Bob Sleigh, host of Nik will present “The Birth, Life, and Extraordinary Death of WPMC’s Morel Mushroom Walk with Indiana County Friends of a Mushroom Spore.” In addition, WPMC President Richard the Parks on April 30. Bob wrote “Second time to find morels Jacob will present an update of our DNA barcoding program. in PA in March. If the weather holds, next weekend should be The day will include guided walks, mushroom identification the time to start some serious hunting.” Alas, the next week tables, a cooking demo with Chef George Harris, sales table, was cool, with snow on the ground and freezing temperatures authors’ book signing, auction and, of course, the legendary at night. -

BACKPACKING Explore the Great Allegheny Passage with Us! We Will Pedal a Total of 30 Miles out and Back Along the GAP

April – June 2017 Schedule VENTURE OUTDOORS TRAILHEAD Everyone Belongs Outdoors! Board of Directors Did You Know… Alice Johnston, Board Chair Venture Outdoors is a 501(c)3 charitable nonprofit organization. We believe everyone Amanda Beamon, Vice Chair deserves the chance to experience how incredibly fun the outdoors can be, so we provide Darlene Schiller, Co-Secretary the gear, guidance and inspiration to make outdoor recreation part of people’s lives. Robert J. Standish, Co-Secretary Drew Lessard, Treasurer We believe everyone belongs outdoors! Todd Owens, Past Chair Abby Corbin Dennis Henderson David Hunt Support Venture Outdoors and Save with a Yearly Membership Lindsay Patross Go to ventureoutdoors.org/join-us or call 412.255.0564 x.224 to become a New or Marty Silverman Geoff Tolley Renewing Venture Outdoors Member. W. Jesse Ward Your Support Helps Venture Outdoors: David Wolf Membership Levels Student / Senior – $15 • Fund the outings and events that Staff Individual – $25 get you and your family outdoors year-round Joey–Linn Ulrich, Executive Director Dual – $35 Family – $50 • Enable underserved children to PROGRAM DEPARTMENT Trailblazer – $75 learn more about nature and the Lora Woodward, Director environment while developing Paddler – $100 Liz Fager, Community Program Manager outdoor recreation skills Jim Smith, Equipment and Facilities Manager Ranger – $125 Lora Hutelmyer, Youth Program Manager Steward – $250 • Turn volunteers into accomplished Jake Very, Custom Program Coordinator trip leaders while enhancing their Trustee – $500 Billy Dixon, Program Administrator leadership skills and safety training Ken Sikora, Head Trip Leader Specialist Pathfinder – $1,000 KAYAK PITTSBURGH Benefits to You Include: Vanessa Bashur, Director • Discounts on outings, Kayak Pittsburgh Mike Adams, Equipment and Training rentals and season passes Specialist • Shopping savings at Eddie Bauer DEVELOPMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS and Gander Mountain Donna L. -

Newsletter Content

VISTAS AN ALLEGHENY LAND TRUST PUBLICATION | 2017 Q1 Newsletter Content A YEAR IN REVIEW: 2016 2 ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION TEAM & DMH NEWS 3 DONOR RECOGNITION LIST, JOIN OUR BOARD 4-8 NOTES FROM THE LAND 9 EVENTS CALENDAR 10 MEET A STEWARD 11 2016: A Year to Remember by Chris Beichner | President & CEO We won’t soon forget 2016. Just looking at the infographic tells a ALLEGHENY LAND TRUST lot about our accomplishments over the past year. We were busy. 2016 IN REVIEW We accomplished a lot. We are happy with our results. But, the statistics do not tell the entire story, and we’re certainly not done reaching for our goals. Here are a few other ways that made 2016 4 NEW CONSERVATION OF 121 a year we won’t soon forget. AREAS ACRES In August 2016, ALT was officially notified of our national re-ac- protecting sequestering absorbing creditation status by the Land Trust Accreditation Commission. Out of 1,700 land trusts nationwide, we are only one of 350 land CO2 trusts that are nationally accredited. The accreditation status sig- nifies to landowners, funders, and partners that we are committed 40,000 Trees 500,000 lbs 104M gal. of Carbon of Rainwater to a high standard of excellence in all aspects of our operations ALT’s volunteered donated and programming. We began our re-accreditation process in 2015, five years af- ter the original accreditation. It took us 18 months, five rounds of review, and more than 400 hours of time to complete the “audit” 574 5,039 $115,903 Volunteers Hours of In-Kind review of our communication, documentation, and decision pro- Investment cesses. -

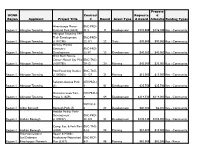

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste D Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type D Award Allocatio Funding Types

Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Alverthorpe Manor BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Cultural Park (6422) 11-3 11 Development $223,000 $136,900 Key - Community Abington Township TAP Trail- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township (1101296) 22-171 22 Trails $90,000 $90,000 Key - Community Ardsley Wildlife Sanctuary- BRC-PRD- Region 1 Abington Township Development 22-37 22 Development $40,000 $40,000 Key - Community Briar Bush Nature Center Master Site Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1007785) 20-12 20 Planning $42,000 $37,000 Key - Community Pool Feasibility Studies BRC-TAG- Region 1 Abington Township (1100063) 21-127 21 Planning $15,000 $15,000 Key - Community Rubicam Avenue Park KEY-PRD-1- Region 1 Abington Township (1) 1 01 Development $25,750 $25,700 Key - Community Demonstration Trail - KEY-PRD-4- Region 1 Abington Township Phase I (1659) 4 04 Development $114,330 $114,000 Key - Community KEY-SC-3- Region 1 Aldan Borough Borough Park (5) 6 03 Development $20,000 $2,000 Key - Community Ambler Pocket Park- Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Ambler Borough (1102237) 23-176 23 Development $102,340 $102,000 Key - Community Comp. Rec. & Park Plan BRC-TAG- Region 1 Ambler Borough (4438) 8-16 08 Planning $10,400 $10,000 Key - Community American Littoral Upper & Middle Soc/Delaware Neshaminy Watershed BRC-RCP- Region 1 Riverkeeper Network Plan (3337) 6-9 06 Planning $62,500 $62,500 Key - Rivers Keystone Fund Projects by Applicant (1994-2017) Propose DCNR Contract Requeste d Region Applicant Project Title # Round Grant Type d Award Allocatio Funding Types Valley View Park - Development BRC-PRD- Region 1 Aston Township (1100582) 21-114 21 Development $184,000 $164,000 Key - Community Comp. -

Manage Goals

Urban forestry and public education services often must compete for funding with established community Urban forestry budgets in US cities are typically allocated for maintenance (58%, includes pruning and services such as law enforcement, fire protection, and infrastructure construction and repair. Decreased removal), planting (14%), and administration (8%). [61, 62] There is no national standard for effective and insufficient funding is one of the greatest challenges facing our nation’s urban forests today. urban forest budget allocation. Planting should be a significant portion of the total budget, second only to maintenance, and generally should not exceed 50% of the operating budget. No doubt the level of funding will determine the viability and sustainability of Pittsburgh’s urban forestry program within the broader context of all of the City’s responsibilities. Only with sufficient financial Pittsburgh’s urban forestry program funding allocation from all sources is generalized; the allocation resources can the City’s urban forestry program best fulfill its mission, respond to change and challenges, should be continually adjusted depending on condition of the trees, planting needs, incidences of severe and serve the public. weather, insect and disease threats, and the desires of the citizens and community leaders at the time budgets are developed. No precise formula exists to determine how much funding is needed for a proactive, sustainable forestry program. There should be sufficient funding for performing preventive tree maintenance, emergency response, and adequate planting, as well as for staff, equipment, and contractual services. Based on reports Current public surveys and feedback indicate that only a minority (14%) of citizens would support a that 3,130 communities submitted to the National Arbor Day Foundation for Tree City, USA certification in special fee or small tax increase to generate additional funds to support urban forest management. -

Allegheny's Riverfronts

ALLEGHENY’S RIVERFRONTS A Progress Report on Municipal Riverfront Development in Allegheny County DECEMBER 2010 Allegheny County Allegheny’s Riverfronts Dear Friends: In Allegheny County, we are known for our rivers. In fact, our rivers have repeatedly been in the national spotlight – during the Forrest L. Wood Cup and Pittsburgh G-20 Summit in 2009, and during World Environment Day in 2010. We are fortunate to have more than 185 miles of riverfront property along the Allegheny, Monongahela, Ohio and Youghiogheny Rivers. Our riverfronts provide opportunities for recreation, conservation and economic development. Providing access to our waterways has always been a key priority and we have been very successful in connecting communities through our trail and greenway system. Through partnerships with businesses, foundations and trail groups, we are on target to complete the Great Allegheny Passage along the Monongahela River before the end of 2011. This trail has been improving the economy and quality of life in towns throughout the Laurel Highlands and Southwestern Pennsylvania, and now its benefits will spread north through the Mon Valley and into the City of Pittsburgh. Our riverfronts provide opportunities for greening our region through the use of new trees, rain gardens and riverside vegetation that aid in flood control, improved water quality and a more natural experience. Allegheny County riverfronts have also always been great places to live. More people will be able to experience riverfront living with the development of communities such as Edgewater at Oakmont, which promises to be one of the best new neighborhoods in the region. I am so proud of all that we have accomplished along our riverfronts and excited about all that is yet to come. -

Ecological Assessment of South Park Methods 8

ALLEGHENY COUNTY PARKS ECOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT AND ACTION PLAN SOUTH PARK Prepared for the Allegheny County Parks Foundation March, 2017 FOREWORD With nine parks encompassing over 12,000 acres, Allegheny County boasts one of the Board of Directors largest regional park systems in the country. While a wide variety of recreational James Mitnick (chair) activities make each park a unique destination, nature is the common thread that connects Ellen Still Brooks (vice chair) our parks and is our most treasured asset. The abundant resources found in our parks’ Rick Rose (treasurer) forests, meadows and streams provide vital habitat for flora and fauna that clean our air Sally McCrady (secretary) and water, pollinate our plants and connect the web of life. We are stewards of these Tom Armstrong natural sanctuaries and are working to protect them for future generations. Chester R. Babst, III In 2016, the Allegheny County Parks Foundation, together with the Allegheny County Andy Baechle Carol R. Brown Parks Department, partnered with the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC) to G. Reynolds Clark conduct an Ecological Assessment and Action Plan in South Park, the second The Honorable John DeFazio collaboration of this type. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the natural resources Karen Wolk Feinstein and ecological assets in South Park and determine an implementation plan for protecting, The Honorable Rich Fitzgerald preserving and improving the environmental health of the park. Pat Getty South Park is a diverse ecosystem with examples of old growth hard wood trees including Laura Karet scarlet and red oaks, American elm, black walnut and butternut hickory; a variety of Jonathan Kersting evergreens; an abundant mix of wildflowers and rare plant species that have a particular Nancy Knauss conservation value in our region. -

COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Forging Our Future 2020 CONTENTS

HARRISON BRACKENRIDGE TARENTUM COMPREHENSIVE PLAN Forging Our Future 2020 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................................ iii SUMMARY.OF.THE.COMPREHENSIVE.PLAN................................................ ES1 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................ 1 SOCIAL.ENTERPRISE,.COMMUNITY,.AND.ECONOMIC.DEVELOPMENT............ 11 STRATEGIES: Improving Social Enterprise, Community and Economic Development ..................... 16 BLIGHT.&.PROPERTY.DETERIORATION........................................................ 35 STRATEGIES: Improving the Condition of Properties and the Effects of Deterioration ................... 38 TRAILS,.PARKS.AND.RECREATION................................................................ 47 STRATEGIES: Improving Trails, Parks & Recreation ........................................................................... 50 COMMUNITY.IDENTITY.AND.BRANDING....................................................... 59 STRATEGIES: Improving Community Identity and Branding ............................................................ 62 ADDITIONAL.TOPICS................................................................................... 65 Appendices.provided.in.companion.document ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS STEERING.COMMITTEE.MEMBERS PUBLIC.OFFICIALS Working Name Community Harrison Group Commissioners Planning. Eric Bengel Harrison Blight William W. Heasley, Commission Robin Trails, Parks, Chairman Harrison Cody Nolen, Chairman -

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program

Pennsylvania Natural Heritage Program information for the conservation of biodiversity WILD HERITAGE NEWS Summer 2021 Life on a Boulderfield Inside This Issue by Jeff Wagner Life on a Boulderfield 1 Green Isn’t Always 4 Good Travel on the many roads running through from the forest edge would feature a little the Appalachian Mountains that make up refugia of its own, supporting a few ferns When Life Gives You 8 Rhus, Make Rhusade! the Ridge and Valley Province of or perennial herbs. Would these rock Sumacs in Pennsylvania and you will notice that a fields eventually become like the adjacent Pennsylvania number of variously shaped, unvegetated forests and woodlands? If these areas are Fifteen Years and 10 rocky patches run down the mountain transitioning, they are doing so slowly. Counting slopes. These boulder strewn patches are One area in eastern Pennsylvania, the Bog Turtle Conservation 10 known by a few names, including Hickory Run State Park boulderfield which and Management boulderfields, scree slopes, rock runs, and is a bit different from typical scree slopes talus slopes. Although prominent, they of the Ridge and Valley in being relatively Characterizing 11 have until recently been given little flat, is documented as shrinking due to Floodplains along the Lehigh River attention, at least from a biological succession. Without the steep downhill perspective. movement, perhaps organic material can Community Scientist 12 accumulate more quickly and Contributes to Invasive The first time I set foot on a scree slope, I accommodate early successional plants. Feeding a Picky Eater 13 sat down on a large rock and Two New Publications! 13 contemplated its origin and tried to explain the pattern of vegetation. -

South Fayette Township Parks Master Site Plans Allegheny County, Pennsylvania

SOUTH FAYETTE TOWNSHIP PARKS MASTER SITE PLANS ALLEGHENY COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA This project was financed in part by a grant from the Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund under the administration of the MAY 12, 2005 Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation. PASHEK ASSOCIATES SOUTH FAYETTE TOWNSHIP ALLEGHENY COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA PARKS MASTER SITE PLANS DCNR PROJECT NUMBER KEY-TAG-9-193 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This project was financed in part by a grant from the Keystone Recreation, Park and Conservation Fund under the administration of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, Bureau of Recreation and Conservation. A special thanks goes out to all of the citizens of South Fayette Township for their enthusiasm and input during this study. Also, the contribution and input of the following individuals were important to the suc- cessful development of this plan: SOUTH FAYETTE TOWNSHIP Michael W. Hoy, Manager Jerry Males, Parks and Recreation Director Sue Caffrey, President, Board of Commissioners Tom Sray, Vice President David Gardner Robert Milacci Ted Villani COMMUNITY PARK STUDY COMMITTEE Linda Defelipo Deb Whitewood Nancy McKinney Terry Gogarty Regina Lubic Lisa Thompson Amanda Evans Bill Collins Debbie Amelio-Manion Tom Sray Tom Reddy Kim Sahady PENNSYLVANIA DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND NATURAL RESOURCES Mr. Wes Fahringer, Recreation and Parks Advisor Ms. Kathy Frankel, Regional Recreation and Parks Advisor TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary. i-v Chapter 1: Background Data Chapter 3: Recommendations and Implementation Introduction (with Location) . 3 Demographics . 3 Master Plan Recommendations. 89 Existing Parks System. 5 Proposed Recreational Facilities . 89 Public Participation . 9 Master Plan Descriptions . -

Armstrong County.Indd

COMPREHENSIVE RECREATION, PARK, OPEN SPACE & GREENWAY PLAN Conservation andNatural Resources,Bureau ofRecreation andConservation. Keystone Recreation, ParkandConservationFund underadministrationofthe PennsylvaniaDepartmentof This projectwas June 2009 BRC-TAG-12-222 fi nanced inpartbyagrantfrom theCommunityConservation PartnershipsProgram, The contributions of the following agencies, groups, and individuals were vital to the successful development of this Comprehensive Recreation, Parks, Open Space, and Greenway Plan. They are commended for their interest in the project and for the input they provided throughout the planning process. Armstrong County Commissioners Patricia L. Kirkpatrick, Chairman Richard L. Fink, Vice-Chairman James V. Scahill, Secretary Armstrong County Department of Planning and Development Richard L. Palilla, Executive Director Michael P. Coonley, AICP - Assistant Director Sally L. Conklin, Planning Coordinator Project Study Committee David Rupert, Armstrong County Conservation District Brian Sterner, Armstrong County Planning Commission/Kiski Area Soccer League Larry Lizik, Apollo Ridge School District Athletic Department Robert Conklin, Kittanning Township/Kittanning Township Recreation Authority James Seagriff, Freeport Borough Jessica Coil, Tourist Bureau Ron Steffey, Allegheny Valley Land Trust Gary Montebell, Belmont Complex Rocco Aly, PA Federation of Sportsman’s Association County Representative David Brestensky, South Buffalo Township/Little League Rex Barnhart, ATV Trails Pamela Meade, Crooked Creek Watershed