Weblogs and the Public Sphere

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journalism's Backseat Drivers. American Journalism

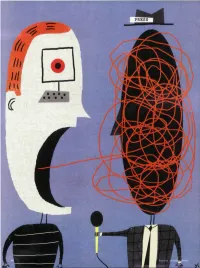

V. Journalism's The ascendant blogosphere has rattled the news media with its tough critiques and nonstop scrutiny of their reporting. But the relationship between the two is nfiore complex than it might seem. In fact, if they stay out of the defensive crouch, the battered Backseat mainstream media may profit from the often vexing encounters. BY BARB PALSER hese are beleaguered times for news organizations. As if their problems "We see you behind the curtain...and we're not impressed by either with rampant ethical lapses and declin- ing readership and viewersbip aren't your bluster or your insults. You aren't higher beings, and everybody out enough, their competence and motives are being challenged by outsiders with here has the right—and ability—to fact-check your asses, and call you tbe gall to call them out before a global audience. on it when you screw up and/or say something stupid. You, and Eason Journalists are in the hot seat, their feet held to tbe flames by citizen bloggers Jordan, and Dan Rather, and anybody else in print or on television who believe mainstream media are no more trustwortby tban tbe politicians don't get free passes because you call yourself journalists.'" and corporations tbey cover, tbat journal- ists tbemselves bave become too lazy, too — Vodkapundit blogger Will Collier responding to CJR cloistered, too self-rigbteous to be tbe watcbdogs tbey once were. Or even to rec- Daily Managing Editor Steve Lovelady's characterization ognize what's news. Some track tbe trend back to late of bloggers as "salivating morons" 2002, wben bloggers latcbed onto U.S. -

Restoring the Ideal Marketplace: How Recognizing Bloggers As Journalists Can Save the Press

\\server05\productn\N\NYL\9-2\NYL202.txt unknown Seq: 1 17-OCT-06 15:39 RESTORING THE IDEAL MARKETPLACE: HOW RECOGNIZING BLOGGERS AS JOURNALISTS CAN SAVE THE PRESS Joseph S. Alonzo* INTRODUCTION In May 2006, a California state appeals court became the first court to explicitly recognize that Internet journalists are afforded the same journalist’s privilege granted to traditional print and broadcast journalists. The defendants in O’Grady v. Superior Court maintained individual websites on which they published trade secrets about an unreleased Apple Computer (Apple) product.1 Unanimously overrul- ing the trial court, the appeals court held that the petitioners were pro- tected by California’s reporter’s shield law and the constitutional journalist’s privilege from being forced to testify about the identity of their sources.2 Because they were publishers of websites, and because they had published not news but the fruits of “trade secret misappropriation,” Apple argued petitioners were not “engaged in legitimate journalistic activities” and were not part of the class of persons protected by the California’s shield law.3 The court determined, however, that the peti- * J.D., 2006, New York University School of Law; B.A., B.J., University of Mis- souri, 2003. Many thanks to Professor Diane Zimmerman and to my colleagues on the New York University Journal of Legislation and Public Policy, for their assistance and for putting up with me. 1. O’Grady v. Superior Court, 44 Cal. Rptr. 3d 72 (Cal. Ct. App. 2006). 2. Id. at 76. 3. Id. at 96–97. As the court explained, the California reporter’s shield is com- prised of two substantially similar sources of law: Article I, section 2, subdivision (b), of the California Constitution pro- vides, “A publisher, editor, reporter, or other person connected with or employed upon a newspaper, magazine, or other periodical publica- tion . -

Online Media and the 2016 US Presidential Election

Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Faris, Robert M., Hal Roberts, Bruce Etling, Nikki Bourassa, Ethan Zuckerman, and Yochai Benkler. 2017. Partisanship, Propaganda, and Disinformation: Online Media and the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election. Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society Research Paper. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33759251 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA AUGUST 2017 PARTISANSHIP, Robert Faris Hal Roberts PROPAGANDA, & Bruce Etling Nikki Bourassa DISINFORMATION Ethan Zuckerman Yochai Benkler Online Media & the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper is the result of months of effort and has only come to be as a result of the generous input of many people from the Berkman Klein Center and beyond. Jonas Kaiser and Paola Villarreal expanded our thinking around methods and interpretation. Brendan Roach provided excellent research assistance. Rebekah Heacock Jones helped get this research off the ground, and Justin Clark helped bring it home. We are grateful to Gretchen Weber, David Talbot, and Daniel Dennis Jones for their assistance in the production and publication of this study. This paper has also benefited from contributions of many outside the Berkman Klein community. The entire Media Cloud team at the Center for Civic Media at MIT’s Media Lab has been essential to this research. -

STAN ANTONIUS VEUGER (Last Updated: November 5, 2019)

STAN ANTONIUS VEUGER (last updated: November 5, 2019) Resident Scholar, Economic Policy Studies [email protected] American Enterprise Institute Phone: 202-862-5894 1789 Massachusetts Avenue NW http://www.aei.org/veuger Washington, DC 20036 Twitter: @stanveuger Professional Experience Fall 2019 Visiting Lecturer of Economics, Harvard University 2018-Present Extramural Fellow, Department of Economics, Tilburg University 2017-Present CGC Future World Fellow, IE School of Global and Public Affairs, IE University 2015-Present Editor, AEI Economic Perspectives 2013-Present Resident Scholar, American Enterprise Institute Fall 2018 Visiting Lecturer of Economics, Harvard University 2016-2018 Expert, expertpowerhouse Fall 2016 Visiting Lecturer of Economics, Harvard University 2014-2016 Advisor, Global Horizon Advisory 2012-2013 Research Fellow, American Enterprise Institute 2012-2013 Washington Fellow, National Review Institute 2008-2011 Teaching Fellow, Harvard University 2007 Research Assistant, Harvard University 2005-2006 Teaching Assistant, Universitat Pompeu Fabra Education Ph.D., Economics, Harvard University, 2012 A.M., Economics, Harvard University, 2009 (fields: Public Economics and International Economics) M.Sc., Economics, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Honors, 2005 Master’s in International Management, CEMS - Global Alliance in Management Education, 2004 Doctorandus, Spanish Language and Literature, Universiteit Utrecht, cum laude, 2004 Doctorandus, Business Administration, Erasmus Universiteit Rotterdam, 2004 Peer-Reviewed Publications “Taking My Talents to South Beach (and Back): Evidence from a Superstar Athlete,” (2019) Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics 22:12, 1950-1960. Joint with Daniel Shoag. “Rules versus Home Rule: Local Government Responses to Negative Revenue Shocks,” (2019) National Tax Journal 72:3, 543-574. Joint with Daniel Shoag and Cody Tuttle. “Do Land Use Restrictions Increase Restaurant Quality and Diversity?” (2019) Journal of Regional Science 59:3, 435-451. -

The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election: Divided They Blog

The Political Blogosphere and the 2004 U.S. Election: Divided They Blog Lada A. Adamic Natalie Glance HP Labs Intelliseek Applied Research Center 1501 Page Mill Road Palo Alto, CA 94304 5001 Baum Blvd. Pittsburgh, PA 15217 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT four internet users in the U.S. read weblogs, but 62% of them In this paper, we study the linking patterns and discussion still did not know what a weblog was. During the presiden- topics of political bloggers. Our aim is to measure the degree tial election campaign many Americans turned to the Inter- of interaction between liberal and conservative blogs, and to net to stay informed about politics, with 9% of Internet users uncover any differences in the structure of the two commu- saying that they read political blogs “frequently” or “some- times”2. Indeed, political blogs showed a large growth in nities. Specifically, we analyze the posts of 40 “A-list” blogs 3 over the period of two months preceding the U.S. Presiden- readership in the months preceding the election. tial Election of 2004, to study how often they referred to Recognizing the importance of blogs, several candidates one another and to quantify the overlap in the topics they and political parties set up weblogs during the 2004 U.S. discussed, both within the liberal and conservative commu- Presidential campaign. Notably, Howard Dean’s campaign nities, and also across communities. We also study a single was particularly successful in harnessing grassroots support day snapshot of over 1,000 political blogs. This snapshot using a weblog as a primary mode for publishing dispatches captures blogrolls (the list of links to other blogs frequently from the candidate to his followers. -

6 Ways to Change the World Glenn Reynolds-Style" (2013)

University of Wisconsin Milwaukee UWM Digital Commons Orland Park Public Library (Illinois), 2013 Archive of Challenges to Library Materials 11-13-2013 6 Ways to Change the World Glenn Reynolds-- Style Dave Swindle Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.uwm.edu/orland_park_library_challenge Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Swindle, Dave, "6 Ways to Change the World Glenn Reynolds-Style" (2013). Orland Park Public Library (Illinois), 2013. 53. https://dc.uwm.edu/orland_park_library_challenge/53 This Blog Post is brought to you for free and open access by UWM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Orland Park Public Library (Illinois), 2013 by an authorized administrator of UWM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PJ Lifestyle » 6 Ways to Change the World Glenn Reynolds-Style » Print Page 1 of 21 - PJ Lifestyle - http://pjmedia.com/lifestyle - 6 Ways to Change the World Glenn Reynolds-Style Posted By Dave Swindle On November 12, 2013 @ 6:50 pm In Blogging,Radical Reading Regimen Journal,Writing | 1 Comment This is Week 6 of Season 3 in my new 13 Weeks of Wild Man Writing and Radical Reading Series. Every week day I try to blog about compelling writers, their ideas, and the news cycle’s most interesting headlines. From the primordial, pajamahadeen era of the blogosphere, Glenn Reynolds has been a tremendous influence on untold numbers of writers, bloggers, and New Media troublemakers. While others’ influence has waned and once-dominant voices have now lost their relevance, Glenn has grown brighter as a beacon of hopeful, future-minded light. -

On Any Given Weekday, Glenn Harlan Reynolds ’85 Can Be Found in Two Ways

<script> <author> Jonathan T. Weisberg <head> The Blogfather <p> On any given weekday, Glenn Harlan Reynolds ’85 can be found in two ways. One is to visit his office at the University of Tennessee College of Law, where he is Beauchamp Brogan Distinguished Professor of Law. The other is to surf to his redoubt on the Internet, www.instapundit.com, where he’s known as InstaPundit. </p> 48 |49 YLR Summer 2003 <td><img src= <!-- body --> InstaPundit is a blog—a collection so, new web-based software made updating blogs simple, of thoughts and impressions on politics, technology, and the blogosphere expanded rapidly. But the word current events, culture, and law, with a fusillade of links “blog” hadn’t coalesced into the consensus choice to to other sources of news and opinion. (The word “blog” describe this new kind of website. Some people were call- was created several years ago by eliding “web log” into a ing their sites digests, diaries, or mezines. single compact syllable.) Blogs are composed of posts— When Reynolds started InstaPundit in 2001, he says, individual entries ranging from a few words to a short “I felt like I had a pretty good idea what was going on essay—which descend the page in reverse chronological throughout most of the blogosphere, at least most of the order. Each item is marked with the date and time at ‘political-slash-military-slash-real world’ blogosphere. which it was posted. I never have paid much attention to the cat blogs or the Reynolds updates InstaPundit dozens of times a day, and diet blogs or the Britney Spears blogs, and there are a lot writes about subjects ranging from the war on terrorism to of those.” He used InstaPundit to highlight other interest- gun control to popular movies. -

ALCTS Contact Information ALCTS Office 50 E Huron St

Library Resources & ISSN 0024-2527 Technical Services January 2005 Volume 49, No. 1 TalkLeft, Boing Boing, and Scrappleface Paul Moeller and Nathan Rupp Analog People for Digital Dreams Janet Swan Hill Impact of Full Text on Print Journal Use Steve Black Students As Cataloging Assistants Timothy H. Gatti Challenges for the Future of Library and Archival Preservation Thomas H. Teper Production Benchmarks for Catalogers Mechael D. Charbonneau The Association for Library Collections & Technical Services 49 ❘ 1 ALCTS Contact Information ALCTS Office 50 E Huron St. Chicago, IL 60611-2795 1-800-545-2433, ext. 5038 fax: (312) 280-5033 www.ala.org/alcts [email protected] Charles Wilt Executive Director 1-800-545-2433, ext. 5030 [email protected] Julie Reese Continuing Education and Meetings 1-800-545-2433, ext. 5034 [email protected] ALCTS Advertising ALCTS Advertising 1-800-545-2433, ext. 5038 [email protected] 2004–2005 ALCTS Leaders Carol Pitts Diedrichs President [email protected] Rosann Bazirjian President-Elect [email protected] Brian E.C. Schottlaender Past-President [email protected] Bruce Chr. Johnson Division Councilor [email protected] Mary Case Director-at-Large [email protected] Karen Darling Director-at-Large [email protected] John Duke Director-at-Large [email protected] Lisa German Acquisition Section Chair [email protected] Sara Shatford Layne Cataloging and Classification Section Chair [email protected] Bonnie Cox Collection Management and Development Section Chair [email protected] Cynthia Clark Council of Regional Groups Chair [email protected] Yvonne Carignan Preservation & Reformatting Section Chair [email protected] Lauren Corbett Serials Section Chair [email protected] Katherine Walter Budget and Finance Committee Chair [email protected] Karen Letarte Education Committee Chair [email protected] Jennifer Paustenbaugh Fundraising Committee Chair [email protected] M. -

Crimson Recriminations Larry Summers Vs

ments and feedback from readers. Andrew Sullivan, complained last May Glenn Reynolds, the University of about his grueling schedule and won- Tennessee law professor who writes dered “what the half-life of a blogger the popular Instapundit blog, told is.” (He seems to have found out: In Wired News last summer that he gets February, he announced a hiatus from e-mails from people asking if he’s blogging.) A huge number of blogs— alright if he hasn’t posted in several the majority, in fact—are abandoned hours. With his hundreds of thousands within just a few months. of readers every day, Reynolds some- This doesn’t mean that blogging times says he feels like a “public utili- must always be terribly demanding—it ty.” Another blogger, James Lileks, need not be if the blogger does not described the demands of the blogging wish it to be—or that bloggers neces- routine: “This is an odd hobby. It’s like sarily put themselves at personal risk. having a train set, a gigantic train set Rather, it suggests that blogging is not in the basement, and in the morning for everyone, and that as this new you not only find a derailment, you medium develops and comes fully into find people streaming out of the tiny its own, those suited to take part will houses yelling at you.” slowly separate themselves from those And some finally succumb to “blog not made for the blogosphere, and this fatigue” and give up. Describing the medium, too, will turn out to be only wearying interaction that led him to for those of a certain stripe. -

Introduction

A Tale of Two Blogospheres: Discursive Practices on the Left and Right1 March, 2010 Yochai Benklera, b and Aaron Shawa,c aBerkman Center for Internet and Society, Harvard University; bHarvard Law School; cDepartment of Sociology, University of California, Berkeley A Tale of Two Blogospheres 2 Abstract Discussions of the political effects of the Internet and networked discourse tend to presume consistent patterns of technological adoption and use within a given society. Consistent with this assumption, previous empirical studies of the United States political blogosphere have found evidence that the left and right are relatively symmetric in terms of various forms of linking behavior despite their ideological polarization. In this paper, we revisit these findings by comparing the practices of discursive production and participation among top U.S. political blogs on the left, right, and center during Summer, 2008. Based on qualitative coding of the top 155 political blogs, our results reveal significant cross-ideological variations along several important dimensions. Notably, we find evidence of an association between ideological affiliation and the technologies, institutions, and practices of participation across political blogs. Sites on the left adopt more participatory technical platforms; are comprised of significantly fewer sole-authored sites; include user blogs; maintain more fluid boundaries between secondary and primary content; include longer narrative and discussion posts; and (among the top half of the blogs in our sample) more often use blogs as platforms for mobilization as well as discursive production. Our findings speak to two major theoretical debates on the political effects of the Internet and networked discourse. First, the variations we observe between the left and right wings of the U.S. -

ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994

Update on the 141 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWS Since Inception of the Program in 1994 24th Annual Robert Novak Journalism Fellowship Awards Dinner May 10, 2017 2017 ROBERT NOVAK JOURNALISM FELLOWSHIP AWARD WINNERS HELEN R. ANDREWS | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Eminent Boomers: The Worst Generation from Birth to Decadence” Helen earned a degree in religious studies from Yale University, where she served as speaker of the Yale Political Union. Currently a freelance writer and commentator, she served for three years as a policy analyst for the Centre for Independent Studies, a leading conservative think tank in suburban Sydney, Australia. Previously, she was an associate editor at National Review. Her work has appeared in First Things, Claremont Review of Books, The American Spectator, The Weekly Standard and others. MADISON E. ISZLER | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “What’s Killing Middle-Aged White Women—and What it Means for Society” Madison holds a master’s degree, cum laude, in political philosophy and economics from The King’s College. Currently, she is an Intercollegiate Studies Institute Reporting Fellow. She has interned for USA Today and the National Association of Scholars and was a reporter for the New York Post. Her work has appeared in numerous outlets, including the Raleigh News & Observer, Charlotte Observer, New York Post and Miami Herald. Originally from Florida, she resides in Raleigh, North Carolina. RYAN LOVELACE | PART-TIME FELLOWSHIP Project: “Hiding in Plain Sight: Criminal Illegal Immigration in America” An Illinois native, Ryan attended and played football for the University of Wyoming. He earned a Bachelor of Arts in journalism from Butler University. -

Influence on Journalism

Joan Shorenstein Center on the Press, Politics and Public Policy Discussion Paper Series A Symbiotic Relationship Between Journalists and Bloggers By Richard Davis Fellow, Shorenstein Center, Spring 2008 Professor of Political Science, Brigham Young University #D-47 © 2008 President and Fellows of Harvard College. All rights reserved. On March 22, 2007, John Edwards’ presidential campaign announced that the candidate and his wife would hold an important press conference that afternoon. Shortly before the press conference, CNN, Fox News, and other cable networks began broadcasting stories that Edwards’ wife, Elizabeth, would announce that her breast cancer was no longer in remission and that her husband would suspend his presidential campaign. While the story spread across the Internet, the campaign told journalists the rumor was not true. However, the campaign’s denial failed to halt the spread of the story. The problem was that the story really was false. When the news conference occurred, the Edwards family announced they would continue their campaign despite the cancer news. Journalists struggled to explain how and why they had given out false information. The source for the news media accounts turned out to be a recently-created blog called Politico.com. In contravention of traditional journalistic standards, the blogger, a former Washington Post reporter, had reported the rumor after hearing it from only one source. The source turned out to be uninformed. The journalist justified his use of only one source, saying that blogs “share information in real time.”1 The Edwards’ campaign story highlights a problem for journalists sharing information “in real time.” While a reporter is seeking confirmation, he or she may find the initial source to be wrong.