Eligibility for Relief: Cancellation of Removal for Permanent Residents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

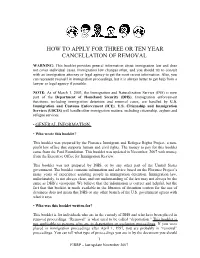

How to Apply for a Three Or Ten Year Cancellation of Removal

HOW TO APPLY FOR THREE OR TEN YEAR CANCELLATION OF REMOVAL WARNING: This booklet provides general information about immigration law and does not cover individual cases. Immigration law changes often, and you should try to consult with an immigration attorney or legal agency to get the most recent information. Also, you can represent yourself in immigration proceedings, but it is always better to get help from a lawyer or legal agency if possible. NOTE: As of March 1, 2003, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) is now part of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Immigration enforcement functions, including immigration detention and removal cases, are handled by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) will handle other immigration matters, including citizenship, asylum and refugee services. • GENERAL INFORMATION • Who wrote this booklet? This booklet was prepared by the Florence Immigrant and Refugee Rights Project, a non- profit law office that supports human and civil rights. The money to pay for this booklet came from the Ford Foundation. This booklet was updated in November, 2007 with money from the Executive Office for Immigration Review. This booklet was not prepared by DHS, or by any other part of the United States government. The booklet contains information and advice based on the Florence Project’s many years of experience assisting people in immigration detention. Immigration law, unfortunately, is not always clear, and our understanding of the law may not always be the same as DHS’s viewpoint. We believe that the information is correct and helpful, but the fact that this booklet is made available in the libraries of detention centers for the use of detainees does not mean that DHS or any other branch of the U.S. -

U.S. Citizenship Law and the Means For

U.S. Department of Justice http://eoirweb/library/lib_index.htm Executive Office for Immigration Review Published since 2007 Immigration Law Advisor November 2008 A Monthly Legal Publication of the Executive Office for Immigration Review Vol 2. No.11 U.S. Citizenship Law and the Means for The Immigration Law Advisor is a professional monthly Becoming a Citizen newsletter produced by the by Katherine Leahy Executive Office for Immigration Review. The purpose of the n this election year, perhaps more than any other in recent memory, publication is to disseminate immigration issues have been at the forefront of the policy debate. judicial, administrative, IHowever, the very last matter on the minds of Americans who regulatory, and legislative rank immigration as an important political issue are the rather obscure developments in immigration law legal doctrines of derived and acquired citizenship. These concepts pertinent to the mission of the provided an interesting (albeit tangential) footnote to the presidential Immigration Courts and Board of race, as both Arizona Senator John McCain and one of his opponents Immigration Appeals. It is intended for the Republican nomination, former Massachusetts Governor Mitt only to be an educational resource for Romney, can point to the operation of the law of acquired citizenship in the use of employees of the Executive their recent family histories. Office for Immigration Review. Article II of the U.S. Constitution requires that the President of the United States be a “natural born citizen,” which led some to question whether McCain, who was born in the Panama Canal Zone while his In this issue.. -

REINSTATEMENT of REMOVAL by Trina Realmuto 2

PRACTICE ADVISORY 1 REINSTATEMENT OF REMOVAL by Trina Realmuto 2 April 29, 2013 “Reinstatement of removal” is a summary removal procedure pursuant to § 241(a)(5) of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA), 8 U.S.C. § 1231(a)(5), 8 C.F.R. § 241.8. With some statutory and judicial exceptions, discussed below, the reinstatement statute applies to noncitizens who return to the United States illegally after having been removed under a prior order of deportation, exclusion, or removal. Reinstatements generally account for more deportations than any other source.3 This practice advisory provides an overview of the reinstatement statute and implementing regulations, including how the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) issues and executes reinstatement orders. The advisory addresses who is covered by § 241(a)(5), where and how to obtain federal court and administrative review of reinstatement orders, and potential arguments to challenge reinstatement orders in federal court. Finally, the advisory includes a sample reinstatement order, a sample letter to DHS requesting a copy of the reinstatement order, a checklist for potential challenges to reinstatement orders, and an appendix of published reinstatement decisions. 1 Copyright (c) 2013, American Immigration Council and National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild. Click here for information on reprinting this practice advisory. This advisory is intended for lawyers and is not a substitute for independent legal advice provided by a lawyer familiar with a client’s case. Counsel should independently confirm whether the law in their circuit has changed since the date of this advisory. 2 Trina Realmuto is a Staff Attorney with the National Immigration Project of the National Lawyers Guild. -

Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen

Fordham Law Review Volume 75 Issue 5 Article 10 2007 Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen Mae M. Ngai Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Mae M. Ngai, Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen, 75 Fordham L. Rev. 2521 (2007). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Birthright Citizenship and the Alien Citizen Cover Page Footnote Professor of History, Columbia University. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol75/iss5/10 BIRTHRIGHT CITIZENSHIP AND THE ALIEN CITIZEN Mae M. Ngai* The alien citizen is an American citizen by virtue of her birth in the United States but whose citizenship is suspect, if not denied, on account of the racialized identity of her immigrant ancestry. In this construction, the foreignness of non-European peoples is deemed unalterable, making nationality a kind of racial trait. Alienage, then, becomes a permanent condition, passed from generation to generation, adhering even to the native-born citizen. Qualifiers like "accidental" citizen,1 "presumed" citizen,2 or even "terrorist" citizen3 have been used in political and legal arguments to denigrate, compromise, and nullify the U.S. citizenship of "unassimilable" Chinese, "enemy-race" Japanese, Mexican .aA X4 -1,;- otreit." "illegal aliens," 1.1 -U1 .-O-.. -

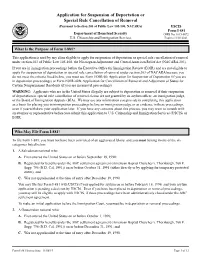

Form I-881, Application for Suspension of Deportation

Application for Suspension of Deportation or Special Rule Cancellation of Removal (Pursuant to Section 203 of Public Law 105-100, NACARA) USCIS Form I-881 Department of Homeland Security OMB No. 1615-0072 U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Expires 11/30/2021 What Is the Purpose of Form I-881? This application is used by any alien eligible to apply for suspension of deportation or special rule cancellation of removal under section 203 of Public Law 105-100, the Nicaraguan Adjustment and Central American Relief Act (NACARA 203). If you are in immigration proceedings before the Executive Office for Immigration Review (EOIR) and are not eligible to apply for suspension of deportation or special rule cancellation of removal under section 203 of NACARA because you do not meet the criteria listed below, you must use Form EOIR-40, Application for Suspension of Deportation (if you are in deportation proceedings) or Form EOIR-42B, Application for Cancellation of Removal and Adjustment of Status for Certain Nonpermanent Residents (if you are in removal proceedings). WARNING: Applicants who are in the United States illegally are subject to deportation or removal if their suspension of deportation or special rule cancellation of removal claims are not granted by an asylum officer, an immigration judge, or the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA). We may use any information you provide in completing this application as a basis for placing you in immigration proceedings before an immigration judge or as evidence in these proceedings, even if you withdraw your application later. If you have any concerns about this process, you may want to consult with an attorney or representative before you submit this application to U.S. -

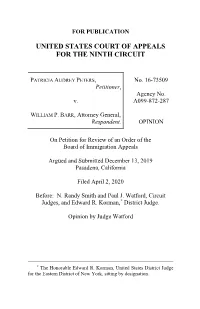

Peters V. Barr

FOR PUBLICATION UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT PATRICIA AUDREY PETERS, No. 16-73509 Petitioner, Agency No. v. A099-872-287 WILLIAM P. BARR, Attorney General, Respondent. OPINION On Petition for Review of an Order of the Board of Immigration Appeals Argued and Submitted December 13, 2019 Pasadena, California Filed April 2, 2020 Before: N. Randy Smith and Paul J. Watford, Circuit Judges, and Edward R. Korman,* District Judge. Opinion by Judge Watford * The Honorable Edward R. Korman, United States District Judge for the Eastern District of New York, sitting by designation. 2 PETERS V. BARR SUMMARY** Immigration The panel granted Patricia Audrey Peters’s petition for review of a Board of Immigration Appeals’ decision, holding that Peters remains eligible for adjustment of status because she reasonably relied on her attorney’s assurances that he had filed the petition necessary to maintain her lawful status, and therefore, her failure to maintain lawful status was through no fault of her own. An individual is barred from adjusting status to become a lawful permanent resident if he or she “has failed (other than through no fault of his own or for technical reasons) to maintain continuously a lawful status since entry into the United States.” 8 U.S.C. § 1255(c)(2). However, skilled workers such as Peters remain eligible for adjustment of status as long as they have not been out of lawful status for more than 180 days. Peters argued that she fell out of lawful status through no fault of her own because either: 1) her attorney timely filed the necessary petition (as he said he did) and it was misplaced; or 2) the attorney did not file the petition. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 16-991 In the Supreme Court of the United States JEFFERSON B. SESSIONS III, ATTORNEY GENERAL, PETITIONER v. ALTIN BASHKIM SHUTI ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI NOEL J. FRANCISCO Acting Solicitor General Counsel of Record CHAD A. READLER Acting Assistant Attorney General EDWIN S. KNEEDLER Deputy Solicitor General ROBERT A. PARKER Assistant to the Solicitor General DONALD E. KEENER BRYAN S. BEIER Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether 18 U.S.C. 16(b), as incorporated into the Immigration and Nationality Act’s provisions governing an alien’s removal from the United States, is unconstitu- tionally vague. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below ................................................................................ 1 Jurisdiction ...................................................................................... 1 Statement ......................................................................................... 2 Argument ......................................................................................... 5 Conclusion ........................................................................................ 6 Appendix A — Court of appeals opinion (July 7, 2016) .............................................. 1a Appendix B — Board of Immigration Appeals decision (July 24, 2015) .......................................... 22a Appendix C -

Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends

Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends Updated February 3, 2015 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R43892 Alien Removals and Returns: Overview and Trends Summary The ability to remove foreign nationals (aliens) who violate U.S. immigration law is central to the immigration enforcement system. Some lawful migrants violate the terms of their admittance, and some aliens enter the United States illegally, despite U.S. immigration laws and enforcement. In 2012, there were an estimated 11.4 million resident unauthorized aliens; estimates of other removable aliens, such as lawful permanent residents who commit crimes, are elusive. With total repatriations of over 600,000 people in FY2013—including about 440,000 formal removals—the removal and return of such aliens have become important policy issues for Congress, and key issues in recent debates about immigration reform. The Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) provides broad authority to the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) to remove certain foreign nationals from the United States, including unauthorized aliens (i.e., foreign nationals who enter without inspection, aliens who enter with fraudulent documents, and aliens who enter legally but overstay the terms of their temporary visas) and lawfully present foreign nationals who commit certain acts that make them removable. Any foreign national found to be inadmissible or deportable under the grounds specified in the INA may be ordered removed. The INA describes procedures for making and reviewing such a determination, and specifies conditions under which certain grounds of removal may be waived. DHS officials may exercise certain forms of discretion in pursuing removal orders, and certain removable aliens may be eligible for permanent or temporary relief from removal. -

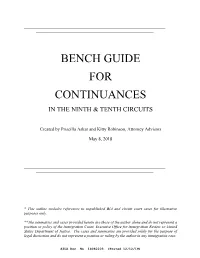

Bench Guide for Continuances in the Ninth & Tenth Circuits

BENCH GUIDE FOR CONTINUANCES IN THE NINTH & TENTH CIRCUITS Created by Priscilla Askar and Kitty Robinson, Attorney Advisors May 8, 2018 * This outline includes references to unpublished BIA and circuit court cases for illustrative purposes only. **The summaries and cases provided herein are those of the author alone and do not represent a position or policy of the Immigration Court, Executive Office for Immigration Review or United States Department of Justice. The cases and summaries are provided solely for the purpose of legal discussion and do not represent a position or ruling by the author in any immigration case. AILA Doc. No. 18082203. (Posted 12/12/19) CONTINUANCES Table of Contents I. “Good Cause” .................................................................................................................... 2 A. In General................................................................................................................ 2 B. Good Cause Factors in the Ninth Circuit under Ahmed .......................................... 2 C. Speculative Relief ................................................................................................... 4 II. Judicial Review of Denial of Continuance ...................................................................... 4 A. In General................................................................................................................ 4 B. Judicial Review in the Ninth Circuit ....................................................................... 4 C. Judicial Review -

Aliens (Consolidation) Act

K:\Flygtningeministeriet\2002\bekg\510103\510103.fm 31-10-02 10:7 k03 pz Consolidation Act No. 608 of 17 July 2002 of the Danish Ministry of Refugee, Immigration and Integration Affairs Aliens (Consolidation) Act The following is a consolidation of the Aliens Act, cf. Consolidation Act No. 711 of 1 August 2001, with the amendments following from Act No. 134 of 20 March 20021), section 2 of Act No. 193 of 5 April 2002, Act No. 362 of 6 June 2002, section 1 of Act No. 365 of 6 June 2002 and Act No. 367 of 6 June 20022). Parts of the amendments following from Act No. 134 of 20 March 2002 and Act No. 367 of 6 June 2002 have not been incorporated into this Consolidation Act, as the amendments have not yet entered into force. The time of their entering into force will be determined by the Minister, cf. section 2 of the Acts. Part I EC rules only to the extent that these limitations are compatible with those rules. Aliens' entry into and stay in Denmark (4) The Minister for Refugee, Immigration and 1. Nationals of Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Integration Affairs lays down more detailed pro- Sweden may enter and stay in Denmark without visions on the implementation of the rules of the special permission. European Community on visa exemption and on 2. (1) Aliens who are nationals of a country abolition of entry and residence restrictions in which is a member of the European Community connection with the free movement of workers, or comprised by the Agreement on the European freedom of establishment and freedom to pro- Economic Area may enter and stay in Denmark vide and receive services, etc. -

Adjustment of Status for VWP Entrants PM

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services Office of the Director (MS 2000) Washington, DC 20529-2000 November 14, 2013 PM-602-0093 Policy Memorandum SUBJECT: Adjudication of Adjustment of Status Applications for Individuals Admitted to the United States Under the Visa Waiver Program Purpose This policy memorandum (PM) provides guidance on the adjudication of Form I-485, Application to Register or Adjust Status, filed by immediate relatives of U.S. citizens who were last admitted under the Visa Waiver Program (VWP). This PM updates the Adjudicator’s Field Manual (AFM) by adding a new section (j) to Chapter 10.3 and 23.5 (AFM Update AD11-30). Scope This PM applies to, and is binding on, all U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) employees, unless specifically exempt. Authority • Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) sections 217, 245 and 245(c)(4) • 8 CFR 245.1(b) Background The VWP allows qualifying foreign nationals of designated countries to enter the United States for up to 90 days to conduct business or for pleasure without first obtaining a visa.1 Before a foreign national is admitted under the VWP, in addition to meeting certain requirements, he or she must waive the right to contest any action for removal, other than on the basis of an application for 1 INA section 217(a)(1). Pursuant to INA section 217(a)(1), an individual seeking admission under the VWP applies for admission as a nonimmigrant, as that term is defined in INA section 101(a)(15)(B), and is provided with a waiver of the visa requirement. -

20190619135814870 18-725 Barton Opp.Pdf

No. 18-725 In the Supreme Court of the United States ANDRE MARTELLO BARTON, PETITIONER v. WILLIAM P. BARR, ATTORNEY GENERAL ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR THE RESPONDENT IN OPPOSITION NOEL J. FRANCISCO Solicitor General Counsel of Record JOSEPH H. HUNT Assistant Attorney General DONALD E. KEENER JOHN W. BLAKELEY TIMOTHY G. HAYES Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the stop-time rule, which governs the cal- culation of an alien’s period of continuous residence in the United States for purposes of eligibility for cancel- lation of removal, may be triggered by an offense that “renders the alien inadmissible,” 8 U.S.C. 1229b(d)(1)(B), when the alien is a lawful permanent resident who is not seeking admission. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below .............................................................................. 1 Jurisdiction .................................................................................... 1 Statement ...................................................................................... 1 Argument ....................................................................................... 6 Conclusion ................................................................................... 14 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases: Ardon v. Attorney Gen. of U.S., 449 Fed. Appx. 116 (3d Cir. 2011) ......................................................................