In Our Schools

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Darynn Zimmer Is an Active Soprano, Producer, Recording Artist and Educator

Darynn Zimmer is an active soprano, producer, recording artist and educator. She has sung with international and American festivals, orchestras and regional operatic companies: Spoleto (USA & Italy); Orquestra Petrobras, Rio; Aspen Opera Theater; American Music Theater Festival; Cen- ter for Contemporary Opera; American Opera Projects: Encompass New Opera Theater: Greens- boro; Skylight and Tampa, performing contemporary and standard repertoire by Bach, Copland, Anthony Davis, Donizetti, Foss, Glass, Monteverdi, Orff and Somei Satoh, among many others. She has appeared as soprano soloist at Carnegie Hall, Alice Tully Hall, Merkin Concert Hall, and the Morgan Library, and with conductors such as Marin Alsop, Bradley Lubman, Paul Nadler, Anton Coppola, David Randolph, Robert Bass and Richard Westenburg. In recent engagements, Ms. Zimmer performed at the 2016 Bergedorfer Musiktage, the largest summer festival in Hamburg. She was invited to perform the Children’s Songs, Op.13, by Mieczyslaw Weinberg in Chamber Music at the Scarab Club in Detroit, a performance co-spon- sored by Michigan Opera Theater to highlight their production of The Passenger. She per- formed these songs again in Miami, in connection with the production at Florida Grand Opera. As performer and co-producer, Ms. Zimmer was part of ‘Ciao, Philadelphia 2015’ festival in, “Introducing B Cell City,” a multi-media work in progress addressing cancer and the environ- ment. Ms. Zimmer sang ‘Elizabeth Christine,’ in a Center for Contemporary Opera showcase of Scott Wheeler’s opera, The Sorrows of Frederick. She appeared in the world premiere of Zin- nias: The Life of Clementine Hunter by Toshi Reagon and Bernice Johnson Reagon, directed by Robert Wilson. -

REGION I0 - MARINE Seymour Schiff 603 Mead Terrace, South Hempstead NY 11550 Syschiff @ Optonline.Net

REGION I0 - MARINE Seymour Schiff 603 Mead Terrace, South Hempstead NY 11550 syschiff @ optonline.net Alvin Wollin 4 Meadow Lane, Rockville Centre NY 11 570 After a series of unusually warm winters and a warm early December, we went back to the reality of subnormal cold and above normal snow. For the three months, temperatures were, respectively, 1.3"F, 4.6" and 4.5" below normal, with a season low 8" on 16 February. This season's average temperature was 10" below last year. Precipitation was very slightly above normal for December, half of normal for January, fifty percent above normal in February, with half of it in the form of snow. On 7 February, 5" fell. And an additional 19" fell on the 16-17th, for the fourth snowiest month on record. The warm early weather induced an unusual number of birds to stay far into the season and kept some for the entire winter. On the other hand, there were absolutely no northern finches, except for a very few isolated Pine Siskins. On 14 December, a Pacific Loon in basic plumage was found by Tom Burke, Gail Benson and Bob Shriber at Camp Hero on the Montauk CBC. It was subsequently seen there and at the point by others on 24,27 and 28 December. On 28 December, Guy Tudor saw a Greater Shearwater sail in toward Montauk Point before returning out to sea. This is a very late record. A Least Bittern, apparently hit by a car "somewhere in East Hampton" on 25 February, was turned over to a local rehabilitator. -

Mario Ferraro 00

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Ferraro Jr., Mario (2011). Contemporary opera in Britain, 1970-2010. (Unpublished Doctoral thesis, City University London) This is the unspecified version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/1279/ Link to published version: Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 MARIO JACINTO FERRARO JR PHD in Music – Composition City University, London School of Arts Department of Creative Practice and Enterprise Centre for Music Studies October 2011 CONTEMPORARY OPERA IN BRITAIN, 1970-2010 Contents Page Acknowledgements Declaration Abstract Preface i Introduction ii Chapter 1. Creating an Opera 1 1. Theatre/Opera: Historical Background 1 2. New Approaches to Narrative 5 2. The Libretto 13 3. The Music 29 4. Stage Direction 39 Chapter 2. Operas written after 1970, their composers and premieres by 45 opera companies in Britain 1. -

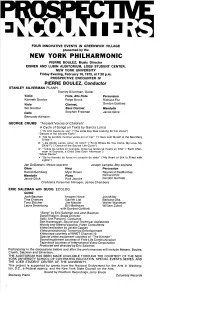

Prospective Encounters

FOUR INNOVATIVE EVENTS IN GREENWICH VILLAGE presented by the NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC PIERRE BOULEZ, Music Director EISNER AND LUBIN AUDITORIUM, LOEB STUDENT CENTER, NEW YORK UNIVERSITY Friday Evening, February 18, 1972, at 7:30 p.m. PROSPECTIVE ENCOUNTER IV PIERRE BOULEZ, Conductor STANLEY SILVERMAN PLANH Stanley Silverman, Guitar Violin Flute, Alto Flute Percussion Kenneth Gordon Paige Brook Richard Fitz Viola Clarinet, Gordon Gottlieb Sol Greitzer Bass Clarinet Mandolin Cello Stephen Freeman Jacob Glick Bernardo Altmann GEORGE CRUMB "Ancient Voices of Children" A Cycle of Songs on Texts by Garcia Lorca I "El niho busca su voz" ("The Little Boy Was Looking for his Voice") "Dances of the Ancient Earth" II "Me he perdido muchas veces por el mar" ("I Have Lost Myself in the Sea Many Times") III "6De d6nde vienes, amor, mi nino?" ("From Where Do You Come, My Love, My Child?") ("Dance of the Sacred Life-Cycle") IV "Todas ]as tardes en Granada, todas las tardes se muere un nino" ("Each After- noon in Granada, a Child Dies Each Afternoon") "Ghost Dance" V "Se ha Ilenado de luces mi coraz6n de seda" ("My Heart of Silk Is Filled with Lights") Jan DeGaetani, Mezzo-soprano Joseph Lampke, Boy soprano Oboe Harp Percussion Harold Gomberg Myor Rosen Raymond DesRoches Mandolin Piano Richard Fitz Jacob Glick PaulJacobs Gordon Gottlieb Orchestra Personnel Manager, James Chambers ERIC SALZMAN with QUOG ECOLOG QUOG Josh Bauman Imogen Howe Jon Miller Tina Chancey Garrett List Barbara Oka Tony Elitcher Jim Mandel Walter Wantman Laura Greenberg Bill Matthews -

The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) Spring 4-27-2013 Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976 David Allen Chapman Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Chapman, David Allen, "Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The hiP lip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966-1976" (2013). All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs). 1098. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/etd/1098 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses and Dissertations (ETDs) by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of Music Dissertation Examination Committee: Peter Schmelz, Chair Patrick Burke Pannill Camp Mary-Jean Cowell Craig Monson Paul Steinbeck Collaboration, Presence, and Community: The Philip Glass Ensemble in Downtown New York, 1966–1976 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2013 St. Louis, Missouri © Copyright 2013 by David Allen Chapman, Jr. All rights reserved. CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................... -

Cerebration Or Celebration David Mcallester

Cerebration or Celebration David McAllester Until recently the place of performance in a liberal arts education was hardly a matter of debate where the arts of liberal arts were concerned. Performance in the arts has been considered distinctly second class, infra dig, base, common, and popular, at least from the time of the ascendency of the German university system, that enormously influential prototype of "civi- lized" education all over the world. No doubt, Plato's mistrust of the arts as unreal ("the shadow of a shadow") but nevertheless able to disrupt ration- ality lies behind the purdah they have enjoyed so widely and so long. This was not always the case. Some of our "Old Ones" in Greece and China considered performance in music, poetry, and sometimes even paint- ing and dance to be necessary parts of a proper education. Traces of this wisdom remain with us to this day. Mao Tse-Tung and Emperor Hirohito are honored for their poetic skill, as are not a few South American generals and presidents. The North European-Platonic blight has not been quite universal in its effects, but we need to remember how low we have fallen: dance relegated to "phys. ed.," performance confined to conservatories granting degrees in "science" rather than in "arts" and elsewhere denied academic credit. This state of affairs is all the more strange when one reflects on the in- sistence upon performance in other areas of liberal knowledge. Proficiency in languages is measured by fluency; the physicist must show his skill in the laboratory; anthropologists and geologists, as other examples, earn their spurs in their field work. -

"Recent Development of Ethnomusicological Studies in Indonesia After Kunts Visits in 1930'S" Abstract

"Recent Development of Ethnomusicological Studies in Indonesia after Kunts Visits in 1930's" By Triyono Bramantyo (ISI Yogyakarta, Indonesia) Abstract It was a remarkable effect scientifically that soon after the late Kunst visits in Indonesia during the early 1930s that the development of non-Western music studies all over the world had had become so quickly developed. The name Jaap (or Jacob) Kunst is always associated to the study of the gamelan music of Indonesia for since then, after one of his PhD students, so-called Mantle Hood, completed his study on the topic of “The Nuclear Theme as a Determinant of Patet in Javanese Music” in 1954, the gamelan studies and practice has become developed throughout the world best known universities. Accordingly, in the USA alone there are now more than 200 gamelan groups have been established. The ideas and the establishment of ethnomusicology would not be happened if Jaap Kunst, as an ethnologist, had never been visited Indonesia in his life time. His visit to Indonesia was also at the right time when the comparative musicology have no longer popular amongst the Western scholars. His works have become world-widely well known. Amongst them were written whilst he was in Indonesia; i.e. the Music of Bali (1925 in Dutch), the Music of Java (originally in Dutch in 1934, last English edition 1973), Music in New Guinea (1967), Music in Nias (1939), Music in Flores (1942) and numerous other books, publications, recordings and musical instruments collections that made Jaap Kunst as the most outstanding scholar on the study of Indonesian musical traditions. -

067609-SEM News

SEM Newsletter Published by the Society for Ethnomusicology Volume 39 Number 3 May 2005 SEM Soundbyte were alluding to the phrase that Marga- SEM 50 LAC Update ret Mead used in her book title, Coming By Timothy Rice, SEM President of Age in Samoa. Mead was discussing By Tong Soon Lee, Emory University the transition from adolescence to adult- On Aging and Anniversaries hood, and we likewise were alluding to The SEM 50 Local Arrangements Committee is continuing its preparation A few years ago, while hiking over the maturation of the society, and by th the lava flows on Hawai’i’s Kilauea extension, the field of inquiry. The for the 50 anniversary conference of volcano, I was amazed to realize that I ethnographic approach used by Ameri- the Society for Ethnomusicology in At- was walking on earth younger than I can scholars was beginning to be well lanta, November 16-20, 2005. Ongoing was. It is almost equally surprising to established as a mode of inquiry. Like- plans are being made to prepare for the realize that our Society, celebrating its wise, by 1980 most major institutions musical performances and events at the 50th anniversary this year, is also younger taught courses in ethnomusicology. conference hotel and at Emory. than I am. It didn’t dawn on me when Even SEM was becoming a mature schol- The structure of the pre-conference I entered graduate school in 1968 that arly organization.” Setting aside for the symposium is gradually shaping up and the discipline to which I would devote moment what she might have meant by here is a tentative outline of the day. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Made Mantle Hood, BA MA Dr. Phil

CURRICULUM VITAE Made Mantle Hood, BA MA Dr. Phil Universiti Putra Malaysia Department of Music Faculty of Human Ecology Phone +6011 2190 8050 Email: [email protected] ________________________________ Summary: • Assoc. Prof. of Ethnomusicology, Universiti Putra Malaysia (2012- present) • Research Fellow, Melbourne University (2011-2013) • Lecturer in Ethnomusicology, Monash University (2005-2011) • UNESCO-enDorsed ICTM InDonesian Liaison Officer • Research Grants (2005-2014) - AUD$41,785 • German AcaDemic Exchange Service (DAAD) scholarship recipient (2002-04), University of Cologne • 16 current anD past MA/PhD graduate supervisions • Languages: English, InDonesian, German anD Balinese Education: 2014 – GraDuate Supervision Training, CADe, UPM 2013 – Certificate in Basic Learning and Teaching, CADe, UPM 2007 – Level II GraDuate Supervision Training (HDR), Monash University 2005 – Dr Phil, ethnomusicology, University of Cologne, Germany 2001 – MA ethnomusicology, University of Hawaii, USA 1992 – BA ethnomusicology, University of Maryland, USA Scopus Publications 2016 – ‘Notating Heritage Musics: Preservation anD Practice in ThailanD, InDonesia anD Malaysia. Malaysian Music Journal. 5(1): 54-74. 2015 – ‘Sustainability Strategies Among Balinese Heritage Ensembles’. Malaysian Music Journal. 3(2): 1-12. Made Mantle Hood 2014 - Sonic Modernities in the Malay World: A History of Popular Music, Social Distinction, and Novel Lifestyles. BarenDragt, B. (eD). review in Wacana Seni Journal of Arts Discourse, Universiti Sains Malaysia Press, Vol. 3. 97-101. 2014 - (with Chan, C. anD Tey, M.). "Acoustic Control, Noise Measurement anD Performance Ambition: Issues SurrounDing Noise Exposure for Musicians". Advances in Environmental Biology 8(15), p. 51-56. 2010 – "Gamelan Gong GeDe: Negotiating Musical Diversity in Bali’s Highlands". Musicology Australia, vol. 32 no. 1, 69-93. -

Ethnomusicology Archive Open Reel Tape Collection

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6b69s042 No online items Finding Aid for the Ethnomusicology Archive Open Reel Tape Collection Processed by Ethnomusicology Archive staff.. Ethnomusicology Archive UCLA 1630 Schoenberg Music Building Box 951657 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1657 Phone: (310) 825-1695 Fax: (310) 206-4738 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.ethnomusic.ucla.edu/Archive/ © 2012 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the 2008.03 1 Ethnomusicology Archive Open Reel Tape Collection Descriptive Summary Title: Ethnomusicology Archive Open Reel Tape Collection Collection number: 2008.03 Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library. Ethnomusicology Archive Los Angeles, California 90095-1490 Abstract: Physical location: Paper index at Ethnomusicology Archive; tapes stored at SRLF Access Collection is open for research. Publication Rights Some materials in these collections may be protected by the U.S. Copyright Law (Title 17, U.S.C.) and/or by the copyright or neighboring-rights laws of other nations. Additionally, the reproduction of some materials may be restricted by terms of Ethnomusicology Archive gift or purchase agreements, donor restrictions, privacy and publicity rights, licensing and trademarks. Transmission or reproduction of protected items beyond that allowed by fair use requires the written permission of the copyright owners. The nature of historical archival collections means that copyright or other information about restrictions may be difficult or even impossible to determine. Whenever possible, the Ethnomusicology Archive provides information about copyright owners and other restrictions in the finding aids. The Ethnomusicology Archive provides such information as a service to aid patrons in determining the appropriate use of an item, but that determination ultimately rests with the patron. -

Ardea Arts__Rep Sheet__2017 Copy

ARDEA ARTS Repertory & Current Projects Commissioned & Developed by Ardea Arts Development & Premiere Partner: University of Kentucky Opera Theatre (UKOT) Music: Glen Roven, Tomas Doncker, Ansel Elgort Story & Libretto: Charles R Smith Jr. Concept-Direction: Grethe B Holby Development & Premiere Partner: UKOT World Premiere October 2017 in Lexington KY with UKOT 2017 Two major workshops scheduled for Spring-Summer in NYC 2017 Full Staged Workshop & 3 Performances, East Flatbush, Brooklyn 2016 Act I and II Workshop University of Kentucky Opera Theater 2015-2016 Libretto Reading & Dramatization: WNYC-live-steamed and broadcast WQXR 2015 Community Engagement Performance Event: Coney Island with City Parks Foundation 2014 Major Support National Endowment for the Arts, Opera America, Jody and John Arnhold, Pam & Bill Michealcheck, Richenthal Foundation, Lynn Schneider, Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund, and many individual donors Commissioned & Developed by Ardea Arts Music: Kitty Brazelton Libretto: George Plimpton, Origin, Dramaturgy, Direction: Grethe Barrett Holby Development Partners: Atlantic Center for the Arts, Montclair State University World Concert Premiere in partnership with Garden State Philharmonic, NJ 2017 Full Semi-Staged Concert Presentatiions Ardea Arts/FOI, Chelsea Studios NYC 2008 Act II Workshop Montclair State University, NJ - Peak Performance Series 2006 Act I Workshop; Atlantic Center for the Arts, FL & Ardea Arts, NYC 2005 DJ Workshop Family Opera Initiative NYC 2004 Major support The Jaffe Family Foundation and many -

Seemansts CV 8-2010SHORT

Sonia Tamar Seeman [email protected] Ernest and Sarah Butler School of Music MBE 3.204 1 University Station E3100 University of Texas, Austin Austin TX 78712-0435 (512) 471-2854 I. ACADEMIC HISTORY 2002-2004 Post-Doctoral Faculty Fellowship, University of California, Santa Barbara. 2002 Ph.D. in Ethnomusicology. University of California, Los Angeles. Dissertation: “’You’re Roman!’ Music and Identity in Turkish Roman Communities”. Prof. Tim Rice; Prof. Jihad Racy, co-chairs. M. A. in Ethnomusicology. University of Washington. Three Master’s Thesis Papers: “Continuity and Transformation in the Macedonian Genre of Chalgija: Past Perfect and Present Imperfective”; “Analytical Modes for Variant Performances of Kuperlika”; “Music in the Service of Prestation: The Case of the Roma of Skopje, Macedonia.” Prof. Christopher Waterman, chair. BA in Music History/Musicology with High distinction. University of Michigan. A.Awards and Honors Fall 2009 Walter and Gina Ducloux and Dean’s Fellowship 2009-2010 Fellowship, Humanities Institute, University of Texas, Austin 2007-2008 Fellowship, Humanities Institute, University of Texas, Austin 2006-2007 Fellowship, Center for Women’s and Gender Studies, University of Texas, Austin. 2002-2004 Post-Doctoral Visiting Faculty Fellowship; University of California, Santa Barbara. 2001 Ki Mantle Hood Award, Best Student Paper. Southern California Chapter, Society for Ethnomusicology. 2000-2001 Collegium of University Teaching Fellows, University of California, Los Angeles. 1999-2000 Graduate Division Dissertation Year Fellowship, University of California, Los Angeles. 1999-2000 Jewish Community Scholarship Award. 1991-1994 Graduate Fellowship, School of Music, University of California, Los Angeles. B.Research Grants; Projects Summer 2010 College of Fine Arts Summer Research Grant, University of Texas, Austin.