The Case of Karachi, Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Result of PRE-ADMISSION ENTRY TEST

INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL & CULTURAL STUDIES University of The Punjab Result of PRE-ADMISSION ENTRY TEST for M.Phil/PhD in Sociology/Gender Studies 2011 Note: The Interview of the candidates (who secured 50 marks and above) will be held on Monday, 22nd August 2011 (Roll No. 01 to 166) and Tuesday 23rd August 2011 at 09:00 am (Roll No. 168 to 325) in the Institute of Social & Cultural Studies, Punjab University, New Campus, Lahore Total Makrs: 100 Pass Marks: 50 Obtained Roll # Name Father's Name Remarks marks 1 Muhammad Ali Khan Muhammad Sharafat Ali 45 Fail 2 Hafiz Muhmmad Waqas Rafique Mian Muhammad Rafique 42.5 Fail 3 Mian Muhmmad Ahmad Iqbal Muhammad Iqbal 41.5 Fail 4 Shahid Iqbal Muhammad Akhlaque 39 Fail 5 Syyeda Mouwaddat Batool Rizvi Syed Mohammad Hussain Rizvi 65 Pass 6 Nighat Yasmeen Khalil Akhtar 80.5 Pass 7 Azhar Rashid Ch. Abdul Rahsid 42 Fail 8 Arfa Bashir Bashir Ahmad 33 Fail 9 Ayesha Siddique Muhammad Siddique Absent 10 Makia Aslam Malik Aslam 53 Pass 11 Muhammad Irfan Khan Rana Abdul Ghafar Khan 55.5 Pass 12 Mirza Muhammad Ali Baig Mirza Tariq Naveed Baig 28 Fail 13 Maria Ali Dilawar Ali 50 Pass 14 Mariam Malik Malik Muhammad Hussain 44.5 Fail 15 Nayab Javed Muhammad Javed 49 Fail 16 Muhammad Aurangzeb Muhammad Aslam 51 Pass 17 Mehmoona Tayyaba Muhammad Ishaq 39.5 Fail 18 Abu-Al-Hassan Manzoor Ahmad Manzoor 41 Fail 19 Asif Iqbal Iqbal Nasir Absent 20 Mahwish Bukhari Syed Babar Bukhari 28.5 Fail 21 Maham Naqvi Tanveer Ahmad Naqvi 28 Fail 22 Amna Latif Latif Ahmad 35.5 Fail 23 Osama Ahmad Khan Fazal Rahim 38.5 Fail 24 Khuram -

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

Withheld File 2020 Dividend D-8.Xlsx

LOTTE CHEMICAL PAKISTAN LIMITED FINAL DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR ENDED 31 DECEMBER 2020 @7.5% RSBOOK CLOSURE FROM 14‐APR‐21 TO 21‐APR‐21 S. NO WARRANT NO FOLIO NO NAME NET AMOUNT PAID STATUS REASON 1 8000001 36074 MR NOOR MUHAMMAD 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 2 8000002 47525 MS ARAMITA PRECY D'SOUZA 927 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 3 8000003 87080 CITIBANK N.A. HONG KONG 382 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 4 8000004 87092 W I CARR (FAR EAST) LTD 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 5 8000005 87094 GOVETT ORIENTAL INVESTMENT TRUST 1,530 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 6 8000006 87099 MORGAN STANLEY TRUST CO 976 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 7 8000007 87102 EMERGING MARKETS INVESTMENT FUND 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 8 8000008 87141 STATE STREET BANK & TRUST CO. USA 1,626 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 9 8000009 87147 BANKERS TRUST CO 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 10 8000010 87166 MORGAN STANLEY BANK LUXEMBOURG 191 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 11 8000011 87228 EMERGING MARKETS TRUST 58 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 12 8000012 87231 BOSTON SAFE DEPOSIT & TRUST CO 96 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 13 8000017 6 MR HABIB HAJI ABBA 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 14 8000018 8 MISS HISSA HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 15 8000019 9 MISS LULU HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 16 8000020 10 MR MOHAMMAD ABBAS 18 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 17 8000021 11 MR MEMON SIKANDAR HAJI ABBAS 12 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 18 8000022 12 MISS NAHIDA HAJI ABBAS 0 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 19 8000023 13 SAHIBZADI GHULAM SADIQUAH ABBASI 792 WITHHELD NON‐CNIC/MANDATE 20 8000024 14 SAHIBZADI SHAFIQUAH ABBASI -

Migration and Small Towns in Pakistan

Working Paper Series on Rural-Urban Interactions and Livelihood Strategies WORKING PAPER 15 Migration and small towns in Pakistan Arif Hasan with Mansoor Raza June 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Arif Hasan is an architect/planner in private practice in Karachi, dealing with urban planning and development issues in general, and in Asia and Pakistan in particular. He has been involved with the Orangi Pilot Project (OPP) since 1982 and is a founding member of the Urban Resource Centre (URC) in Karachi, whose chairman he has been since its inception in 1989. He is currently on the board of several international journals and research organizations, including the Bangkok-based Asian Coalition for Housing Rights, and is a visiting fellow at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), UK. He is also a member of the India Committee of Honour for the International Network for Traditional Building, Architecture and Urbanism. He has been a consultant and advisor to many local and foreign CBOs, national and international NGOs, and bilateral and multilateral donor agencies. He has taught at Pakistani and European universities, served on juries of international architectural and development competitions, and is the author of a number of books on development and planning in Asian cities in general and Karachi in particular. He has also received a number of awards for his work, which spans many countries. Address: Hasan & Associates, Architects and Planning Consultants, 37-D, Mohammad Ali Society, Karachi – 75350, Pakistan; e-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]. Mansoor Raza is Deputy Director Disaster Management for the Church World Service – Pakistan/Afghanistan. -

SEP SWEEP 30 June 2020 ESMS

Stakeholder Engagement Plan Solid Waste Emergency and Efficiency Project (SWEEP) July 24th 2020 Table of Contents 1. Introduction/Project Description ................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Project Description..................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Potential Social and Environmental Risks ........................................................................................ 2 2. Brief Summary of Previous Stakeholder Engagement Activities ..................................................... 4 2.1. Summary of Consultations in SWEEP Project Preparation Phase .......................................... 4 3. Stakeholder Identification and Analysis .................................................................................................... 7 3.1. Project Affected Parties ............................................................................................................................ 8 3.2. Other Interested Parties ......................................................................................................................... 12 3.3. Disadvantaged / Vulnerable Groups ................................................................................................. 13 3.4. Summary of Project Stakeholder Needs .......................................................................................... 15 4. Stakeholder Engagement Program -

Schedule for Written Test for the Posts of Lecturers in Various Disciplines

SCHEDULE FOR WRITTEN TEST FOR THE POSTS OF LECTURERS IN VARIOUS DISCIPLINES Please be informed that written test for the posts of Lecturers in the following departments / disciplines shall be conducted by the University of Sargodha as per schedule mentioned below: Post Applied for: Date & Time Venue 16.09.2018 Department of Business LECTURER IN LAW (Sunday) Administration, (MAIN CAMPUS) University of Sargodha, 09:30 am Sargodha. Roll # Name & Father’s Name 1. Mr. Ahmed Waqas S/o Abdul Sattar 2. Ms. Mahwish Mubeen D/o Mumtaz Khan 3. Malik Sakhi Sultan Awan S/o Malik Abdul Qayum Awan 4. Ms. Sadia Perveen D/o Manzoor Hussain 5. Mr. Hassan Nawaz Maken S/o Muhammad Nawaz Maken 6. Mr. Dilshad Ahmed S/o Abdul Razzaq 7. Mr. Muhammad Kamal Shah S/o Mufariq Shah 8. Mr. Imtiaz Ali S/o Sahib Dino Soomro 9. Mr. Shakeel Ahmad S/o Qazi Rafiq Ahmad 10. Ms. Hina Sahar D/o Muhammad Ashraf 11. Ms. Tahira Yasmeen D/o Sheikh Nazar Hussain 12. Mr. Muhammad Kamran Akbar S/o Mureed Hashim Khan 13. Mr. M. Ahsan Iqbal Hashmi S/o Makhdoom Iqbal Hussain Hashmi 14. Mr. Muhammad Faiq Butt S/o Nazzam Din Butt 15. Mr. Muhammad Saleem S/o Ghulam Yasin 16. Ms. Saira Afzal D/o Muhammad Afzal 17. Ms. Rubia Riaz D/o Riaz Ahmad 18. Mr. Muhammad Sarfraz S/o Ijaz Ahmed 19. Mr. Muhammad Ali Khan S/o Farzand Ali Khan 20. Mr. Safdar Hayat S/o Muhammad Hayat 21. Ms. Mehwish Waqas Rana D/o Muhammad Waqas 22. -

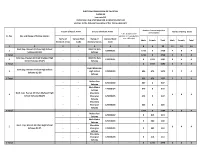

National Assembly Polling Scheme

ELECTION COMMISSION OF PAKISTAN FORM-28 [see rule 50] LIST OF POLLING STATIONS FOR A CONSTITUENCY OF Election to the National Assembly of the NA-66 JHELUM-I Number of voters assigned to In Case of Rural Areas In Case of Urban Areas Number of polling booths polling station S. No. of voters on the Sr. No. No. and Name of Polling Station electoral roll in case electoral Name of Census Block Name of Census Block area is bifurcated Male Female Total Male Female Total Electoral Areas Code Electoral Areas Code 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Govt Cap. Hasnat Ali Khan High School Moh Eid Gah 1 - - 125050101 1716 0 1716 4 0 4 Sohawa (M) (P) Sohawa 1 Total - - - 1716 0 1716 4 0 4 Govt Cap. Hasnat Ali Khan Shaheed High Moh Eid Gah 2 - - 125050101 0 1593 1593 0 4 4 School Sohawa (F) (P) Sohawa 2 Total - - - 0 1593 1593 0 4 4 Hydri Mohallah Govt Cap. Hasnat Ali Khan High School 3 - - High School 125050103 696 676 1372 2 2 4 Sohawa (C) (P) Sohawa 3 Total - - - 696 676 1372 2 2 4 Mohra Pari - - 125050102 407 0 407 Sohawa Moh Madni - - 125050104 679 0 679 Sohawa Govt. Cap. Hasnat Ali Khan Shaheed High Khurakha 4 4 0 4 School Sohawa (M) (P) - - Khengran 125050105 472 0 472 Sohawa Khurakha - - Khengran 125050106 226 0 226 Sohawa 4 Total - - - 1784 0 1784 4 0 4 Mohra Pari - - 125050102 0 413 413 Sohawa Moh Madni - - 125050104 0 680 680 Sohawa Govt. -

Health Bulletin July.Pdf

July, 2014 - Volume: 2, Issue: 7 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: Polio spread feared over mass displacement 02 English News 2-7 Dengue: Mosquito larva still exists in Pindi 02 Lack of coordination hampering vaccination of NWA children 02 Polio Cases Recorded 8 Delayed security nods affect polio drives in city 02 Combating dengue: Fumigation carried out in rural areas 03 Health Profile: 9-11 U.A.E. polio campaign vaccinates 2.5 million children in 21 areas in Pakistan 03 District Multan Children suffer as Pakistan battles measles epidemic 03 Health dept starts registering IDPs to halt polio spread 04 CDA readies for dengue fever season 05 Maps 12,14,16 Ulema declare polio immunization Islamic 05 Polio virus detected in Quetta linked to Sukkur 05 Articles 13,15 Deaths from vaccine: Health minister suspends 17 officials for negligence 05 Polio vaccinators return to Bara, Pakistan, after five years 06 Urdu News 17-21 Sewage samples polio positive 06 Six children die at a private hospital 06 06 Health Directory 22-35 Another health scare: Two children infected with Rubella virus in Jalozai Camp Norwegian funding for polio eradication increased 07 MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES ADULT HEALTH AND CARE - PUNJAB MAPS PATIENTS TREATED IN MULTAN DIVISION MULTAN HEALTH FACILITIES 71°26'40"E 71°27'30"E 71°28'20"E 71°29'10"E 71°30'0"E 71°30'50"E BUZDAR CLINIC TAYYABA BISMILLAH JILANI Rd CLINIC AMNA FAMILY il BLOOD CLINIC HOSPITAL Ja d M BANK R FATEH MEDICAL MEDICAL NISHTER DENTAL Legend l D DENTAL & ORAL SURGEON a & DENTAL STORE MEDICAL COLLEGE A RABBANI n COMMUNITY AND HOSPITAL a CLINIC R HOSPITALT C HEALTH GULZAR HOSPITAL u "' Basic Health Unit d g CENTER NAFEES MEDICARE AL MINHAJ FAMILY MULTAN BURN UNIT PSYCHIATRIC h UL QURAN la MATERNITY HOME CLINIC ZAFAR q op Blood Bank N BLOOD BANK r ishta NIAZ CLINIC R i r a Rd X-RAY SIYAL CLINIC d d d SHAHAB k a Saddiqia n R LABORATORY FAROOQ k ÷Ó o Children Hospital d DECENT NISHTAR a . -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Unclaimed Deposits

Annexure-A Statement of Unclaimed Deposits/Instruments Surrendered to SBP 2012 1166 SILKBANK LIMITED DETAILS OF THE BRANCH DETAILS OF THE DEPOSITORS/BENIFICARY OF THE INSTRUMENT DETAILS OF THE ACCOUNT DETAILS OF THE INSTRUMENT Transaction NAME OF PROVINCE IN Nature of Federal/Provincial Rate Rate applied Last date of deposit or WHICH ACCOUNT CNIC No/ Deposit Account Type Instrument Type Currency FCS S. No Name of the (FED/PRO) in case of Type Rate of PKR date Amount Eqv.PKR withdrawal Remarks code Name OPENED/INSTRUMENT Passport Name Address (LCY,UFZ,F Account Number ( e.g Current, Saving, (DD,PO,FDD,TDR, Instrument No. Date of Issue (USD,EUR,GBP,A Contract No Applicant/Purchaser Instrument Favoring the (MTM,F conversion (DD-MON- Outstanding surrendered (DD-MON-YYYY) PAYABLE No Z) Fixed or any other) CO) ED,JPY,CHF) (if any) Government CSR) YYYY) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 1 0001 Karachi Main Branch SD SADAF SHOAIB. 1ST FLOOR,6-C,SOUTH PARK AVENUE, PHASE II,EXT,D.H.A,KARACHI. LCY 2000113077 PLS PKR 43,170.41 16-Sep-2002 No Response from Depositor. 2 0001 Karachi Main Branch SD MISS WARDAH MEMON. 511,TRADE TOWERS,ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD,KARACHI . LCY 2000115269 PLS PKR 7,056.20 8-Aug-2002 No Response from Depositor. 3 0001 Karachi Main Branch SD ASMA & ZOHRA. OFFICE NO: 5, BHAYANI CENTRE LR 11: SIDDIQUE WAHAB ROAD OLD HAJI CAMP, KARACHI. LCY 2000111921 PLS PKR 13,636.54 6-Mar-2002 No Response from Depositor. -

(Rfp) for Front End Collection and Disposal of Municipal Solid Waste for Zone Korangi (Dmc Korangi Area) Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan

REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) FOR FRONT END COLLECTION AND DISPOSAL OF MUNICIPAL SOLID WASTE FOR ZONE KORANGI (DMC KORANGI AREA) KARACHI, SINDH, PAKISTAN. Executive Director (Operation-I) Sindh Solid Waste Management Board (SSWMB) Govt. of Sindh SSWMB – NIT-16 Table of Content Sindh Solid Waste Management Board Section-I Preamble Clause# Page# 1.1 Purpose of Request for Proposal 8 1.2 Scope of Work/Assignment 8 1.3 Brief Description of DMC Korangi 8 1.4 MAP of DMC Korangi 9 1.5 Definition & Interpretation 9 1.6 Abbreviation 10 1.7 Section of RFP/Bidding Documents 11 1.8 Procuring Agency Right to cancel any or all proposals/tenders 11 Section-II Instructions to Contractors/Bidders. Clause# Page# 2.1 Information related to procuring agency 13 2.2 Language of proposal and correspondence 13 2.3 Method of Procurement 13 2.4 Period of Contract 13 2.5 Pre-proposal Meeting 13 2.6 Clarification and modifications of Bidding Document 14 2.7 Visit of the area of Service 14 2.8 Utilization of Existing Work Force on SWM of DMC Korangi 14 2.9 Utilization of Existing Solid Waste Collection & Transportation Vehicle of 16 DMC Korangi. 2.10 Utilization of Existing Facilities i.e. Workshop, Offices of DMC Korangi 17 2.11 Amendment through Addendums 17 2.12 Cancelation of Tender before Tender Time 17 2.13 Proposal Preparation Cost/Cost of bidding 17 2.14 Bid submitted by a Joint Venture/Consortium 18 2.15 Place, date, time and manner of submission of Tender/Bid Document 19 2.16 Currency Unit of Offers and Payments 21 2.17 Conditional and Partial Offers 22 2.18 -

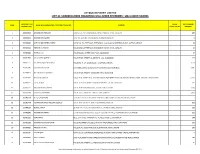

List of Unclaimed Shares and Dividend

ATTOCK REFINERY LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS REGARDING UNCLAIMED DIVIDENDS / UNCLAIMED SHARES FOLIO NO / CDC SHARE NET DIVIDEND S/NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDER / CERTIFICATE HOLDER ADDRESS ACCOUNT NO. CERTIFICATES AMOUNT 1 208020582 MUHAMMAD HAROON DASKBZ COLLEGE, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, PHASE-VI, D.H.A., KARACHI 450 2 208020632 MUHAMMAD SALEEM SHOP NO.22, RUBY CENTRE,BOULTON MARKETKARACHI 8 3 307000046 IGI FINEX SECURITIES LIMITED SUIT # 701-713, 7TH FLOOR, THE FORUM, G-20, BLOCK 9, KHAYABAN-E-JAMI, CLIFTON, KARACHI 15 4 307013023 REHMAT ALI HASNIE HOUSE # 96/2, STREET # 19, KHAYABAN-E-RAHAT, DHA-6, KARACHI. 15 5 307020846 FARRUKH ALI HOUSE # 246-A, STREET # 39, F-11/3, ISLAMABAD 67 6 307022966 SALAHUDDIN QURESHI HOUSE # 785, STREET # 11, SECTOR G-11/1, ISLAMABAD. 174 7 307025555 ALI IMRAN IQBAL MOTIWALA HOUSE NO. H-1, F-48-49, BLOCK - 4, CLIFTON, KARACHI. 2,550 8 307026496 MUHAMMAD QASIM C/O HABIB AUTOS, ADAM KHAN, PANHWAR ROAD, JACOBABAD. 2,085 9 307028922 NAEEM AHMED SIDDIQUI HOUSE # 429, STREET # 4, SECTOR # G-9/3, ISLAMABAD. 7 10 307032411 KHALID MEHMOOD HOUSE # 10 , STREET # 13 , SHAHEEN TOWN, POST OFFICE FIZAI, C/O MADINA GERNEL STORE, CHAKLALA, RAWALPINDI. 6,950 11 307034797 FAZAL AHMED HOUSE # A-121,BLOCK # 15,RAILWAY COLONY , F.B AREA, KARACHI 225 12 307037535 NASEEM AKHTAR AWAN HOUSE # 183/3 MUNIR ROAD , LAHORE CANTT LAHORE . 1,390 13 307039564 TEHSEEN UR REHMAN HOUSE # S-5, JAMI STAFE LANE # 2, DHA, KARACHI. 3,475 14 307041594 ATTIQ-UR-REHMAN C/O HAFIZ SHIFATULLAH,BADAR GENERALSTORE,SHAMA COLONY,BEGUM KOT,LAHORE 7 15 307042774 MUHAMMAD NASIR HUSSAIN SIDDIQUI HOUSE-A-659,BLOCK-H, NORTH NAZIMABAD, KARACHI.