New Agra Reports Offer Little Evidence to Justify Continued Donor Support

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10-Day Golden Triangle and Holy City Tour

www.satguruun.com Contact us at [email protected] 10-DAY GOLDEN TRIANGLE AND HOLY om for more information and CITY TOUR booking! From USD 499 Per Personn Golden Triangle tour is one of the most popular travel packages of India. This tour covers the most popular travel destinations of India Delhi, Jaipur & Agra. Delhi, being the capital and also a historical city of India, has a lot to offer. Highlights: New Delhi & Old Delhi, Jaipur Pink City with Amber fort, Agra With TajMahal at Sunset or Sunrise, Varanasi Morning Boat ride Tour Features Includes: • Roundtrip Transfers from your Delhi hotel. • The above cost include services by air conditioned car. • Services of Local English Speaking Guide (Language speaking guide can be organized at a supplement cost) • Driver & fuel charges. Parking charges. • Aircon. Sleeper Class Train tickets from Agra /Varanasi. • Accommodation in Twin sharing Room including breakfast. (03 Star Hotels). Not included: • Camera charges are not included • Lunch /Dinner can be organized as per request (optional not included in above cost) • Flight Tickets Varanasi/Delhi can • Elephant Ride & Entrance Tickets. • Tips Taj Mahal Day By Day itinerary Golden Triangle tour is one of the most popular Afterwards visit the City Palace, the Palace of spiritually uplifting sight. Stay overnight travel packages of India. This tour covers the Winds. The RoyalObservatory which was at Hotel. most popular travel destinations of India Delhi, built by the Maharajah Jai Singh and shows Jaipur & Agra. Delhi, being the capital and also his passion for astronomy. Stay overnight at Day 09 VARANASI / DELHI (By Hotel. Flight) a historical city of India, has a lot to offer. -

List of Examination Centres for Even Semester Exam 2011 – 12 (MAY-2012) Sr

List of Examination Centres For Even Semester Exam 2011 – 12 (MAY-2012) Sr. Code, Name and Address of List of Institutions whose student shall appear at the examination Code of Nodal Centre No. Examination Centres Centres for Theory Examination to which examination centre is attached 1 2 3 4 5 1 (001) Anand Engineering 1. (002) Faculty Of Engineering & Technology, Agra B. Tech 001 Agra College, Agra College, Agra 2. (006) Agra Public Institute Of Technology & B.Phar Computer Education (Deptt. Of Pharmacy), Agra 3. (243) College Of Pharmacy Agra, Agra B.Phar 4. (314) Sai Nath College Of Pharmacy,Agra B.Phar 5. (617) Uttam Institute Of Management Studies,Agra MBA 6. (659) Heritage Institute Of Hotel & Tourism,Agra BHMCT 2 (003)Babu Mohan Lal Arya 1. (004) R.B.S.College, Faculty Of Engg.& B.Tech 001 Agra Smarak Engg. College, Agra Technology,Agra Agra 2. (278) Aryan Institute Of Management And Computer MBA Studies,Agra 3. (338) K. P. Engineering College ,Agra B.Tech, MBA 4. (436) K. P. College Of Management,Agra MBA 3. (004) R.B.S.College, Faculty Of 1. (001) Anand Engineering College, Agra B.Tech, 001 Agra Engg. & Technology,Agra MBA,MCA 4. (005) Raja Balwant Singh 1. (003) Babu Mohan Lal Arya Smarak Engg. College, B.Tech, MBA 001 Agra College,Agra Agra 5. (064) Hindustan College Of 1. (317) Dhanwantri Institute Of Pharmacy,Mathura B.Phar 001 Agra Science & Technology, Mathura 2. (366) Nikhil Institute Of Engineering & B.Tech, MBA Management,Mathura 3. (394) College Of Business Studies,Agra MBA 4. -

Current Condition of the Yamuna River - an Overview of Flow, Pollution Load and Human Use

Current condition of the Yamuna River - an overview of flow, pollution load and human use Deepshikha Sharma and Arun Kansal, TERI University Introduction Yamuna is the sub-basin of the Ganga river system. Out of the total catchment’s area of 861404 sq km of the Ganga basin, the Yamuna River and its catchment together contribute to a total of 345848 sq. km area which 40.14% of total Ganga River Basin (CPCB, 1980-81; CPCB, 1982-83). It is a large basin covering seven Indian states. The river water is used for both abstractive and in stream uses like irrigation, domestic water supply, industrial etc. It has been subjected to over exploitation, both in quantity and quality. Given that a large population is dependent on the river, it is of significance to preserve its water quality. The river is polluted by both point and non-point sources, where National Capital Territory (NCT) – Delhi is the major contributor, followed by Agra and Mathura. Approximately, 85% of the total pollution is from domestic source. The condition deteriorates further due to significant water abstraction which reduces the dilution capacity of the river. The stretch between Wazirabad barrage and Chambal river confluence is critically polluted and 22km of Delhi stretch is the maximum polluted amongst all. In order to restore the quality of river, the Government of India (GoI) initiated the Yamuna Action Plan (YAP) in the1993and later YAPII in the year 2004 (CPCB, 2006-07). Yamuna river basin River Yamuna (Figure 1) is the largest tributary of the River Ganga. The main stream of the river Yamuna originates from the Yamunotri glacier near Bandar Punch (38o 59' N 78o 27' E) in the Mussourie range of the lower Himalayas at an elevation of about 6320 meter above mean sea level in the district Uttarkashi (Uttranchal). -

Ground Water Scenario of Lakhimpur Kheri District, Up

GROUND WATER SCENARIO OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. (A.A.P.: 2012-2013) By Dr. D.S. Pandey Scientist 'D' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................2 I. INTRODUCTION ..................5 II. CLIMATE & RAINFALL ..................5 III. GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOIL TYPES ..................6 IV. GROUND WATER SCENARIO ..................6 V. GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................8 VI. GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUE AND PROBLEMS ..................9 VII. MASS AWARENESS PROGRAMME ..................9 PLATES: I. INDEX MAP OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. II. PRE-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (MAY, 2012) OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. III. POST-MONSOON DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL MAP (NOV. 2012) OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. IV. DYNAMIC GROUND WATER RESOURCES OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. V. GROUND WATER USER MAP, LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. VI. ARSENIC AFFECTED AREA OF LAKHIMPUR KHERI DISTRICT, U.P. VII. Exploratory Tubewells (C.G.W.B.) For Arsenic Studies DISTRICT AT GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq. Km.) : 7680.00 ii. Administrative Divisions (as on 31.3.2005) Number of Blocks : 6/15 Number of Panchayat Villages : 1829 iii. Population (as on 2001 census) : 32,07,234 iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) : 1093.50 mm 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units : Older & Younger Alluvium Major Drainages : Gomati & Ghaghra 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km.) a) Forest area (Sq. Km.) : 2321.54 b) Net area sown (Sq. Km.) : 4863.82 c) Cultivable area (Sq. Km.) : 4863.82 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES : Sandy Loam 5. AREA UNDER PRINCIPAL CROPS (as on 2004-05) : 6984.20 6. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and Number of Structures) (Sq.Km.) Dugwells : 168 Tubewells / Borewells : 713 state tubewells & 108430 Private tubewells Canals : 641 Km. -

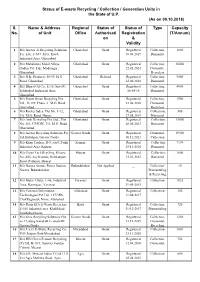

S. No. Name & Address of Unit Regional Office Status of Authorisati

Status of E-waste Recycling / Collection / Generation Units in the State of U.P. (As on 09.10.2018) S. Name & Address Regional Status of Status of Type Capacity No. of Unit Office Authorisati Registration (T/Annum) on & Validity 1 M/s Auctus -E Recycling Solutions Ghaziabad Grant Registered Collection, 1800 Pvt. Ltd., F-637, M.G. Road, 30.08.2019 Dismantle Industrial Area, Ghaziabad. 2 M/s Mahaluxmi Metal Alloys Ghaziabad Grant Registered Collection, 30000 (India) Pvt. Ltd., Modinagar, 22.05.2023 Dismantle, Ghaziabad. Recyclers 3 M/s N.K. Products, 58-59, M.G. Ghaziabad Refused Registered Collection, 9000 Road, Ghaziabad. 22.06.2016 Dismental 4 M/s Bharat Oil Co., E-18, Site-IV, Ghaziabad Grant Registered Collection, 4000 Sahibabad, Industrial Area, 16-05-18 Dismental Ghaziabad. 5 M/s Planet Green Recycling Pvt. Ghaziabad Grant Registered Collection, 1500 Ltd., G-129, Phase -1, M.G. Road, 23.08.2018 Dismental, Ghaziabad. Recyclers 6 M/s Rocket Sales, Plot No. 1-12, Ghaziabad Grant Registered Collection,, 300 I/A, M.G. Raod, Hapur. 27.08.2019 Dismental 7 M/s Arsh Recycling Pvt. Ltd., Plot Ghaziabad Grant Registered Collection, 15000 No. 203, UPSDIC, I/A, M.G. Road, 20.06.2023 Dismental Ghaziabad. 8 M/s Auctus Recycling Solutions Pvt. Greater Noida Grant Registered Dismental, 19500 Ltd.Habibpur, Greater Noida. 06.12.2021 Callection 9 M/s Khan Traders, B-5, site4, Panki Kanpur Grant Registered Collection, 7190 Industrial Area, Kanpur. 15-11-2020 Dismental 10 M/s Green Tech Rcycling, Khasra Meerut Grant Registered Collection, 1800 No.-645, Acchraunds, Bahdaurpur 12.01.2022 Dismental Road, Partapur, Meerut . -

Social Impact Assessment Report

SIA Report of Bundelkhand Expressway Project in District Banda, UP, India SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Bundelkhand Expressway, District Banda, UP, India Submitted to District Collector Banda, Uttar Pradesh Social Responsibility Asia (SR Asia) 4F-CS-25 Ansal Plaza Mall, Vaishali Sector 1 Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, India [email protected] 0 | P a g e S R A S I A SIA Report of Bundelkhand Expressway Project in District Banda, UP, India ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This Social Impact Assessment (SIA) Report is a result of the work executed by SR Asia as per the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 and UP Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Rules, 2016. The research team had extensive consultation with the officials of Department of Revenue and Land Reforms, public representatives and Project Affected Families (PAFs) of 26 villages of Banda District for collecting valuable inputs, data on local ecology, culture and socio-economic profiles. We extend our sincere thanks to all the Office of Collectorate, Department of Revenue and Land Reforms for their continuous support and cooperation. They have been extremely supportive throughout the study with respect to project related information, documents and providing guidance to the team in Banda The team is grateful to the Project Affected Families (PAFs) and local representatives for their time and feedbacks. We appreciate the efforts made by all the participants of this study and thank them for their support. Birendra Raturi International Director, SR Asia 1 | P a g e S R A S I A SIA Report of Bundelkhand Expressway Project in District Banda, UP, India TABLE OF CONTENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ......................................................................................................................... -

Agra Is a City on the Banks of the River Yamuna in the Northern State of Uttar Pradesh, India

AACCTTIIOONN PPLLAANN FFOORR TTHHEE CCOONNTTRROOLL OOFF AAIIRR PPOOLLLLUUTTIIOONN IINN AAGGRRAA CCIITTYY RREEGGIIOONNAALL OOFFFFIICCEE UUTTTTAARR PPRRAADDEESSHH PPOOLLLLUUTTIIOONN CCOONNTTRROOLL BBOOAARRDD 1144,,, SSEECCTTOORR--33 BB,,, AAWWAASS VVIIKKAASS,,, SSIIKKAANNDDRRAA YYOOJJNNAA AAGGRRAA 1.INTRODUCTION Agra is a city on the banks of the river Yamuna in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh, India. It is 378 kilometres west of the state capital, Lucknow, 206 kilometres south of the national capital New Delhi, 58 kilometres south from Mathura and 125 kilometres north of Gwalior. Agra is one of the most populous cities in Uttar Pradesh, and the 24th most populous in India.Agra is a major tourist destination because of its many Mughal-era buildings, most notably the Tāj Mahal, Agra Fort and Fatehpūr Sikrī, all three of which are UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Agra is included on the Golden Triangle tourist circuit, along with Delhi and Jaipur; and the Uttar Pradesh Heritage Arc, tourist circuit of UP state, along Lucknow the capital of the state and Varanasi. Agra city has a population of 1,585,704, while the population of Agra cantonment is 53,053. The urban agglomeration of Agra has a population of 1,760,285 .The city is located at 27.1767° N, 78.0081° E. 2. ACTION TAKEN BY THE BOARD Board has issued directions to Principal Secretary Urban Development, Principal Secretary Forests, Principal Secretary Transport, Principal Secretary Agriculture, Managing Director Central U.P. Gas Ltd., Managing Director Indraprastha Gas Ltd, and Managing Director Green Gas Ltd. under section 31 (A) of the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981 regarding prevention and control of air pollution in Agra city on dated 05.09.2016 in compliance of directions issued by Central Pollution Control Board, Delhi under section 18(1) (b) of the Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981. -

Copy of PSC Address.Xlsx

Address of Program Study Centers S.N Districts Name of Institutes Address Contact No 1 Agra District Women Hospital-Agra Shahid Bhagatsingh Rd, Rajamandi Crossing, Bagh Muzaffar 0562 226 7987 Khan, Mantola, Agra, Uttar Pradesh 282002 2Aligarh District Women Hospital-Aligarh Rasal Ganj Rd, City, Aligarh, Uttar Pradesh 202001 3 Pt. DDU District Combined Hospital-Aligarh Ramghat Rd, Near Commissioner House, Quarsi, Aligarh, 0571 274 1446 Uttar Pradesh 202001 4 Prayagraj District Women Hospital-Prayagraj 22/26, Kanpur - Allahabad Hwy, Roshan Bagh, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh 211003 5 Azamgarh District Women Hospital-Azamgarh Deen Dayal Upadhyay Marg, Balrampur, Harra Ki Chungi, 091208 49999 Sadar, Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh 276001 6 Bahraich District Male Hospital-Bahraich Ghasiyaripura, Friganj, Bahraich, Uttar Pradesh 271801 094150 36818 7 Bareilly District Women Hospital-Bareilly Civil Lines, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh 243003 0581 255 0009 8 Basti District Women Hospital-Basti Ladies hospital, Kateshwar Pur, Basti, Uttar Pradesh 272001 9 Gonda District Women Hospital-Gonda Khaira, Gonda, Uttar Pradesh 271001 11 Etawah District Male Hospital-Etawah Civil Lines, Etawah, Uttar Pradesh 206001 099976 04403 12 Ayodhya District Women Hospital-Ayodhya Fatehganj Rikabganj Road, Rikaabganj, Faizabad, Uttar Pradesh 224001 13 GB Nagar Combined Hospital-GB Nagar C-18, Service Rd, C-Block, Sector 31, Noida, Uttar Pradesh 201301 14 Ghaziabad District Combined Hospital, Sanjay Nagar- District Combined Hospital, Mansi Vihar, Sector 23, Sanjay Ghaziabad Nagar, Ghaziabad, -

HFCL Bags Order Worth Rs.221.16 Crores for Kanpur Metro

HFCL Limited (formerly Himachal Futuristic Communications Ltd .) 8, Commercial Complex, Masjid Moth, Greater Kailash -II, mHFCLGROUP , New Delhi - 110048, India Tel : (+9111) 3520 9400, 3520 9500, Fax: (+9111) 35209525 Web : www.hfcl.com Email [email protected] HFCL/SEC/20-21 March 17, 2021 The BSE Ltd. The National Stock Exchange of India Ltd. 1st Floor, New Trading Wing, Rotunda Building Exchange Plaza, 5th Floor, C - 1, Block G Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Dalal Street, Fort Sandra- Kurla Complex, Bandra (E) Mumbai- 400001 Mumbai- 400051 [email protected] [email protected] Security Code No.: 500183 Security Code No.: HFCL RE: Intimation under Regulation 30 of SEBI (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 (the "SEBI Listing Regulations"). Subject: HFCL bags Order worth U21.16 Crores for Kanpur Metro (Corridor-1 and Corridor-H) and Agra Metro (Corridor-I) Projects from Uttar Pradesh Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. Dear Sir(s)/ Madam, We are pleased to inform all our stakeholders that the Company has bagged an Order worth Rs.221.16 Crores from Uttar Pradesh Metro Rail Corporation Ltd., for Design, Manufacture, Supply, Installation, Testing and Commissioning of Telecommunication Systems for Kanpur Metro (Corridor-! and Corridor-II) and Agra Metro (Corridor-!) Project (the "Project") . The details as required under Regulation 30 of the SEBI Listing Regulations read with SEBI Circular No. CIR/CFD/CMD4/2015 dated 9th September, 2015 , are as under: s. Particulars Details No. a) Name of the entity awarding -

Report on Proposed Plantation Scheme in and Around Agra City

Report on Proposed plantation scheme in and around Agra City Central Pollution Control Board, Delhi, on the basis of values of Particulate Matter (PM10- Particle Matter Size less than 10 micron) in ambient air has identified 15 cities of Uttar Pradesh as Non- attainment cities. Agra is one of the fifteen non attainment city. U P Pollution Control Board prepared draft action plans for 15 non- attainment cities of Uttar Pradesh. The Action Plans comprises of 06 Major categories as given below:- a. Vehicle Emission Control b. Suspension of Road Dust and Fugitive Emission Control c. Control of Emissions form Biomass/ Crop residue/ Garbage/ Municipal Solid Waste burning d. Control of Industrial Emissions e. Control of Air Pollution from constructions and demolition activities. f. Other Steps to Control Air Pollution. The Action Plans comprises of 58 Short and long term Action Points. The short term (immediate) activities which don't need advance preparedness and are to be implemented by concerned department/ agencies immediately and the long term action points require preparedness including making of DPRs, Sanctions, Budget allocation and implementation. Two main action points of this plan to mitigate pollution are to prepare plan for creation of green buffers along the traffic corridors and Plantation of specific types of species of plants which are helpful in pollution control and Tree Plantation for mitigation of air pollution based upon location of pollution sources and Wind rose data. ABOUT THE CITY: Agra - has been immortalized as the City of the Taj. Taj Mahal is the universally admired masterpiece of the world's heritage. -

State District City Address Type Uttar Pradesh Agra

STATE DISTRICT CITY ADDRESS TYPE AXIS BANK ATM, UNIQUE HANDICRAFT 25 T HIG 9 GROUP 10 TAJ UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE NAGRI PHASE 1 AGRA UP 282001 AXIS BANK ATM, ANAND SWAROOP MEMORIAL EDUCATION TRUST UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA ANAND ENGINEERING COLLEGE KEETHAM AGRA MATHURA ROAD NH OFFSITE 2 UTTER PRADESH UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA AXIS BANK ATM, 59/126 , AJIT NAGAR GATE , VIP ROAD AGRA OFFSITE AXIS BANK ATM, 8-B , SOUTH ARJUN NAGAR, AGRA, UTTAR PRADESH UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE 282001 UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA AXIS BANK ATM, 18/204 PURANI MANDI TAJ GANJ AGRA 282001 OFFSITE AXIS BANK ATM, RAKWA NO. 110 , ROHTA KA BAGH , GWALIOR ROAD UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE AGRA , AXIS BANK ATM, SHIROLI MOD SHAYAM MARKET DHNOLI AGRA, UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE UTTAR PRADESH, 282001 AXIS BANK ATM, HOUSE NO 37 202 NEAR AXIS ATM BUNDHU KATRA UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE GWALIOR ROAD AGRA UTTAR PRADESH PIN CODE 282001 AXIS BANK ATM, L 4 OLD MATHURA ROAD OPP CLARKS HOTEL AGRA UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE UP 282002 AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO 1A 79 NAULAKH SADAR BAZAR AGRA UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE CANTT UTTAR PRADESH PIN CODE 282001 AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO B 29 KAMLA NAGAR CENTRAL BANK ROAD UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE AGRA UTTAR PRADESH 282005 AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO 4 221 NEAR RAILWAY CROSSING RUI KI UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE MANDI SHAHGANJ AGRA 282010 AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO C 200 BESIDE LAXMI AUTO TRANS UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE YAMUNA COLONY AGRA 282006 UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA AXIS BANK ATM, F 48 KEDAR NAGAR SHAHGANJ AGRA UP 282010 OFFSITE AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO 1 PLOT NO 44 325 2 NEAR SABZI MANDI UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE PRAHLAD NAGAR BODLA CROSSING AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO 01 B S COMPLEX SECTOR 4 AVAS VIKAS UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE AGRA 282002 AXIS BANK ATM, SHOP NO 4 412 GWALIOR ROAD BALLO GANJ AGRA UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE 282006 AXIS BANK ATM, 31 218 4 RAWAT MKT RAJPUR CHUNGI SAMSABAD UTTAR PRADESH AGRA AGRA OFFSITE ROAD AGRA 282001 AXIS BANK ATM, WARD NO. -

Lucknow-Kanpur-Agra Via Mainpuri Sl.No 1 2 3 4 5

LUCKNOW-KANPUR-AGRA VIA MAINPURI SL.NO 1 2 3 4 5 SERVICE CODE R185 P185 K185 K185 E185 From SONOLI-10:30-GKP ALD-19:00 ARR 23:30 0:30 KANPUR DEP 0 0:15 1:00 6:00 6:15 6:30 ARR 0 2:40 3:25 8:00 8:40 8:30 KANNOJ DEP 81 81 2:45 3:30 8:15 8:45 8:45 ARR 5:05 5:50 10:35 11:05 11:05 MAINPURI DEP 95 176 5:20 6:05 10:50 11:20 11:20 ARR 6:40 7:25 12:20 12:40 12:50 SHIKOHABAD DEP 53 229 6:45 7:30 12:50 12:45 13:20 ARR 8:35 9:20 12:50 14:35 12:50 AGRA DEP 67 296 10:20 TO JAIPUR-16:20 AGRA-KANPUR-LUCKNOW VIA MAINPURI SL. No. 1 2 3 4 5 SERVICE CODE K186 C186 K186 P186 K186 From JAIPUR- 19:20 AJMER 18:00-JAIPUR 22:00 ARR 0:30 3:30 AGRA DEP 0 0:50 4:00 4:15 4:30 4:45 ARR 0 2:20 5:30 5:45 6:00 6:15 SHIKOHABAD DEP 67 67 2:50 5:45 6:15 6:15 6:45 ARR 4:20 7:15 7:45 7:45 8:15 MAINPURI DEP 53 120 4:35 7:30 8:00 8:00 8:30 ARR 6:35 9:30 10:00 10:00 10:30 KANNOJ DEP 95 215 6:50 9:45 10:15 10:15 10:45 ARR 8:50 11:45 12:15 12:15 12:45 KANPUR DEP 81 296 12:30 13:45 13:00 ARR LUCKNOW DEP 90 386 TO HMR-MAHOBA FTP-ALD FATEHPUR-ALD Page 1 of 8 LUCKNOW-KANPUR-AGRA VIA MAINPURI SL.NO 6 7 8 9 10 11 SERVICE CODE K185 K185 K185 R185 K185 R185 From SONOLI-17:00-GKP SONOLI-18:30-GKP ARR 6:00 7:30 KANPUR DEP 0 6:45 7:00 7:15 7:30 8:00 8:15 ARR 0 8:45 9:00 9:40 9:55 10:25 10:40 KANNOJ DEP 81 81 9:00 9:15 9:45 10:00 10:30 10:45 ARR 11:20 11:35 12:05 12:20 12:50 13:05 MAINPURI DEP 95 176 11:35 11:50 12:20 12:35 13:05 13:20 ARR 13:05 13:20 13:40 13:55 14:25 14:40 SHIKOHABAD DEP 53 229 13:35 13:50 13:45 14:00 14:30 14:45 ARR 13:35 13:50 15:35 15:50 16:20 16:35 AGRA DEP 67 296 17:35 16:45 TO JAIPUR-23:20 JAIPUR-22:00 AGRA-KANPUR-LUCKNOW VIA MAINPURI SL.