Range and Pasture Management in Central and Eastern Oregon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forests of Eastern Oregon: an Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, and Dale Weyermann

Forests of Eastern Oregon: An Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, and Dale Weyermann United States Forest Pacific Northwest General Tecnical Report Department of Service Research Station PNW-GTR-578 Agriculture April 2003 Revised 2004 Joseph area, eastern Oregon. Photo by Tom Iraci Authors Sally Campbell is a biological scientist, Dave Azuma is a research forester, and Dale Weyermann is geographic information system manager, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station, 620 SW Main, Portland, OR 97205. Cover: Aspen, Umatilla National Forest. Photo by Tom Iraci Forests of Eastern Oregon: An Overview Sally Campbell, Dave Azuma, and Dale Weyermann U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, OR April 2003 State Forester’s Welcome Dear Reader: The Oregon Department of Forestry and the USDA Forest Service invite you to read this overview of eastern Oregon forests, which provides highlights from recent forest inventories.This publication has been made possible by the USDA Forest Service Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) Program, with support from the Oregon Department of Forestry. This report was developed from data gathered by the FIA in eastern Oregon’s forests in 1998 and 1999, and has been supplemented by inventories from Oregon’s national forests between 1993 and 1996.This report and other analyses of FIA inventory data will be extremely useful as we evaluate fire management strategies, opportunities for improving rural economies, and other elements of forest management in eastern Oregon.We greatly appreciate FIA’s willingness to work with the researchers, analysts, policymakers, and the general public to collect, analyze, and distrib- ute information about Oregon’s forests. -

Conifer Trees of the Umatilla National Forest

Outer bark scales are thin and purplish, covering a reddish inner bark. inner reddish a covering purplish, and thin are scales bark Outer BARK: Poisonous. Coral-red fl eshy (berry-like) cup that is open at one end and contains a single seed. single a contains and end one at open is that cup (berry-like) eshy fl Coral-red Poisonous. FRUITS: 1” long. Have a distinctive pointed tip and form two opposite rows along branches. along rows opposite two form and tip pointed distinctive a Have long. 1” NEEDLES: Up to 40’ in the Blue Mountains. Blue the in 40’ to Up HEIGHT: Washington, northern Idaho, and northwestern Montana. northwestern and Idaho, northern Washington, Southern British Columbia, the Cascades of Washington and Oregon, northern Sierras, eastern Oregon and and Oregon eastern Sierras, northern Oregon, and Washington of Cascades the Columbia, British Southern RANGE: chemical called taxol, extracted from yew bark, was found to be an effective cancer treatment. cancer effective an be to found was bark, yew from extracted taxol, called chemical often square in profi le, eventually becoming cone-shaped with age. Yew wood is used for archery bows and canoe paddles. A A paddles. canoe and bows archery for used is wood Yew age. with cone-shaped becoming eventually le, profi in square often Small conifer tree or large shrub with a square or twisted stem and a broad crown of slender horizontal branches. Young stems are are stems Young branches. horizontal slender of crown broad a and stem twisted or square a with shrub large or tree conifer Small Taxus brevifolia Taxus Pacifi c yew c Pacifi Thin, reddish-brown, furrowed (on older trees) and fi brous or shredded. -

The Columbia River Gorge: Its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway by IRA A

VOLUMB 2 NUMBBI3 NOVBMBBR, 1916 . THE .MINERAL · RESOURCES OF OREGON ' PuLhaLed Monthly By The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology Mitchell Point tunnel and viaduct, Columbia River Hi~hway The .. Asenstrasse'' of America The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations Entered aa oeoond cl,... matter at Corvallis, Ore., on Feb. 10, l9lt, accordintt to tbe Act or Auc. :U, 1912. .,.,._ ;t ' OREGON BUREAU OF MINES AND GEOLOGY COMMISSION On1cm or THm Co><M188ION AND ExmBIT OREGON BUILDING, PORTLAND, OREGON Orncm or TBm DtBIICTOR CORVALLIS, OREGON .,~ 1 AMDJ WITHY COMBE, Governor HENDY M. PABKB, Director C OMMISSION ABTBUB M. SWARTLEY, Mining Engineer H. N. LAWRill:, Port.land IRA A. WILLIAMS, Geologist W. C. FELLOWS, Sumpter 1. F . REDDY, Grants Pass 1. L. WooD. Albany R. M. BIITT8, Cornucopia P. L. CAI<PBELL, Eugene W 1. KEBR. Corvallis ........ Volume 2 Number 3 ~f. November Issue {...j .· -~ of the MINERAL RESOURCES OF OREGON Published by The Oregon Bureau of Mines and Geology ~•, ;: · CONTAINING The Columbia River Gorge: its Geologic History l Interpreted from the Columbia River Highway t. By IRA A. WILLIAMS 130 Pages 77 Illustrations 1916 ILLUSTRATIONS Mitchell Point t unnel and v iaduct Beacon Rock from Columbia River (photo by Gifford & Prentiss) front cover Highway .. 72 Geologic map of Columbia river gorge. 3 Beacon Rock, near view . ....... 73 East P ortland and Mt. Hood . 1 3 Mt. Hamilton and Table mountain .. 75 Inclined volcanic ejecta, Mt. Tabor. 19 Eagle creek tuff-conglomerate west of Lava cliff along Sandy river. -

Ore Bin / Oregon Geology Magazine / Journal

Vol. 30, No. 6 June 1968 STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTIIIES • The Ore Bin • Published Monthly 8y STATE OF OREGON DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGY AND MINERAL INDUSTRIES Head Office: 1069 State Office Bldg., Portland, Oregon - 97201 Telephone: 226 ... 2161, Ext. 488 Field Offices 2033 First Street 521 N. E. liE" Street Bak.. 97814 Grants Pas. 97526 Subscription rote $1 . 00 per year. Available back Issues 10 cents each. • • * • * • * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * • • * * * Second class postage paid at Portland, Oregon • * * * • • * • * • * * • * • • * * • • • * * * * * • • • * * • * • * • * * • GOVERNING BOARD Fronk C . McColloch, Chalrmon, Portland Fayette I. tristol, Gronts Poss Harold Bonta, 8ak..- STATE GEOLOGIST Hollis M. Dole GEOLOGISTS IN CHARGE OF FIELD OFFICES Norman S. Wagner. Boker Len Ramp, Grants PaIS P. mi$$ion is granted to reprint infonl'lCl lion c:onfolned h ..ei n. Any credit given the State of Oregon Deportmen t of Geology ond Mi ner(ll Inmnlries for compiling this information wi ll be opprec:loted . State of Oregon The ORE BI N Department of Geology Volume 30, No.6 and Mineral Indcstries 1069 State Offi ce BI dg. June 1968 Portland Oregon 97201 THE GOLDEN YEARS OF EASTERN OREGON By Mi les F. Potter and Harold McCall The following pictorial article on the golden years of eastern Oregon, by Mi les F. Potter and Harold McCall, is an abstract from their man uscript of a forthcoming book they are calling "Golden Pebbles." Potter is a long-time resident of eastern Oregon and an amateur his torian of some of the early gold camps in Grant and Baker Counties. McCall is a photographer in Oregon City with a keen interest in the history of gold mining. -

Gifts to Umatilla County Organizations, 1997—2005 Year Contrib

Giving In Oregon, 2007 Report on Philanthropy Gifts to Umatilla County Organizations, 1997—2005 Year Contrib. # Orgs Amount 7,000,000 2005 $4,168,286 135 Change from last year: 5.09% 6,000,000 2004 $3,966,333 142 5,000,000 2003 $2,934,263 142 4,000,000 2002 $6,226,783 133 3,000,000 2001 $3,925,226 129 2,000,000 2000 $2,846,613 125 1,000,000 1999 $3,909,754 123 Overall change, 1997 through 2005: 97.16% 0 1998 $2,973,000 121 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 1997 $2,114,153 121 Towns in Umatilla County: Athena; Echo; Helix; Hermiston; Meacham; Milton-Freewater; Pendleton; Pilot Rock; Stanfield; Umatilla; Weston. Data: Oregon Attorney General Charitable Activities Section Giving In Oregon, 2007 Report on Philanthropy Charitable Donations by County — 2005 UMATILLA COUNTY — by NTEE Category NTEE Description (NTEE = National Taxonomy of Exempt Entities) Aggregate Donations Revenue Arts, culture, humanities $805,220 $1,381,994 Education $671,927 $8,158,811 Human services—other, multi-purpose $602,938 $7,319,438 Housing, shelter $542,384 $922,168 Environmental quality, protection $346,848 $1,209,335 Philanthropy & volunteerism $340,273 $428,988 Health, general, rehabilitative $248,946 $83,098,188 Community improvement, development $216,213 $9,157,769 Youth development $127,617 $294,977 Mental health, crisis intervention $112,235 $7,284,761 Recreation, leisure, sports, athletics $80,110 $480,304 Animal-related activities $39,166 $189,648 Public affairs, society benefit $32,799 $32,802 Food, nutrition, agriculture $1,225 $33,200 Civil rights, civil liberties $385 $2,002 Employment, jobs $0 $18,805 Public protection: crime, courts, legal services $0 $58,098 Public safety, disaster preparedness & relief $0 $221,697 Unknown, Unclassifiable $0 $1,681 TOTAL FOR THE PERIOD: $4,168,286 $120,294,666 Total Contributions, all (135) organizations, this county: $4,168,286 Total Revenue, all organizations this county: $120,294,666 Towns in Umatilla County: Athena; Echo; Helix; Hermiston; Meacham; Milton-Freewater; Pendleton; Pilot Rock; Stanfield; Umatilla; Weston. -

Steens Mountain Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Plan

BLM Burns District Office Steens Mountain Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Plan Appendix P - Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and ProtectionWSRP Area Resource Management Plan August 2005 Public Lands USA: Use, Share, Appreciate As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most of our nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use of our land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values of our national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interest of all our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in Island Territories under U.S. administration. Photo courtesy of John Craig. TABLE OF CONTENTS Steens Mountain Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers Plan TABLE OF CONTENTS Acronym List . v Introduction . .1 Plan Organization . .1 Background . .1 Plan Purpose . .1 Relationship to BLM Planning . .2 Public Involvement . .2 Steens Mountain Advisory Council . .2 Area Overview . .2 General Location and Boundaries . .2 Access . .3 Land Ownership . .3 History of Use for Steens Mountain Wilderness and Wild and Scenic Rivers . .4 Steens Mountain Wilderness Overview . .4 Unique Wilderness Attributes . .4 Wilderness Management Areas . .5 Wild and Scenic Rivers Overview . .6 Public Lands in Wild and Scenic River Corridors outside Steens Mountain Wilderness . .7 Outstandingly Remarkable Values . .8 Management Goals and Objectives . .10 Steens Mountain Cooperative Management and Protection Act . -

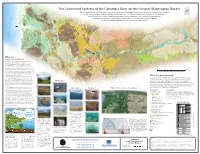

The Connected Systems of the Columbia River on the Oregon

The Connected Systems of the Columbia River on the Oregon-Washington Border WASHINGTON The Columbia River, in its 309-mile course along the Oregon-Washington border, provides a rich and varied environment OREGON for the people, wildlife, and plants living and interacting there. The area’s geology is the basis for the landscape and ecosystems we know today. By deepening our understanding of interactions of Earth systems — geosphere, hydrosphere, atmosphere, and biosphere — Earth science helps us manage our greatest challenges and make the most of vital opportunities. ⑮ ⑥ ④ ⑬ ⑧ ⑪ ① ⑦ ② ③ What is a ⑭ ⑫ ⑤ connected system? ⑩ A connected system is a set of interacting components that directly or indirectly influence one another. The Earth system has four major components. The geosphere includes the crust and the interior of the planet. It contains all of the rocky parts of the planet, the processes that cause them to form, and the processes that have caused ⑨ them to change during Earth’s history. The parts can be as small 0 10 20 40 Miles ∆ N as a mineral grain or as large as the ocean floor. Some processes act slowly, like the gradual wearing away of cliffs by a river. Geosphere Others are more dramatic, like the violent release of gases and magma during a volcanic eruption. ① What is a geologic map? The fluid spheres are the liquid and gas parts of the Earth system. The atmosphere includes the mixture of gases that Geologic maps show what kinds of rocks and structures make up a landscape. surrounds the Earth. The hydrosphere includes the planet’s The geologic makeup of an area can strongly influence the kinds of soils, water water system. -

The "Palouse Soil" Problem with an Account of Elephant Remains in Wind-Borne Soil on the Columbia Plateau of Washington

THE "PALOUSE SOIL" PROBLEM WITH AN ACCOUNT OF ELEPHANT REMAINS IN WIND-BORNE SOIL ON THE COLUMBIA PLATEAU OF WASHINGTON By KIRK BRYAN INTRODUCTION Wheat is the great crop of eastern Washington. Grown on an extensive scale with all the ingenuity of modern labor-saving devices, it forms the basis for the stable prosperity of the " Inland Empire " which has its commercial center at Spokane. Deep, rich soil is the controlling factor in the growth of wheat in this area, for the rain fall is light, though advantageously concentrated in the winter sea son. The system of summer fallow is necessary to conserve the mois ture of one season into the next, but thereby one-half the land lies plowed and idle. The wheat region, therefore, is a checkerboard of bare brown rectangles of plowed land alternating with rectangles of wheat that are green, gold, or buff according to the season. The great Columbia Plateau, underlain except in a few small areas by basalt flows several hundred feet thick, has nearly every where a mantle of so-called soil, deep and retentive of moisture, the basis of this great wheat growing industry. This " soil" * is a fine grained mass that is intimately dissected into hills and valleys. (PI. 4, A and B.) The little valleys are usually cut to or just below the level of the underlying basalt, so that the height of the hills, from 100 to 150 feet, measures the thickness of this " soil." This material is locally known as " Palouse soil," from the rich wheat-growing area along Palouse Kiver south of Spokane, which is popularly known as the " Palouse country." The Bureau of Soils, as shown in the summary of the history of the subject, on pages 22-26, recognizes in the region a number of soil series, only, one of which bears the name Palouse. -

SOUTHEASTSOUTHEAST OREGON 234 Photographing Oregon Southeast Oregon 235

Owyhee Lake at Leslie Gulch Chapter 12 SOUTHEASTSOUTHEAST OREGON 234 Photographing Oregon Southeast Oregon 235 change quickly to howling winds. Unlike the western part of the state, there’s not much chance you’ll run into a bear out here, but it is definitely rattlesnake coun- try. It’s an area of sparse human population, and most of the people who live here like it that way. Cowboy is spoken here. A good way to begin your exploration of this fascinating part of the state is by traveling the Oregon Outback National Scenic Byway, breaking away from the Cascades and journeying south and east into the Great Basin via OR 31. Fort Rock Rising up out of surrounding sagebrush desert, Fort Rock is a towering jagged rock formation, technically a tuff ring, set in an ancient seabed. It is also perhaps the most famous anthropological site in Oregon, as a pair of 9,000–year old sagebrush bark sandals were discovered here. Trails lead up into the bowl of this crater-like formation, and you can scramble to the top for views of the surround- ing desert. Fort Rock has been designated a National Natural Landmark, and an Oregon State Parks interpretive display at the base of the rock does a good job of Lone tree in Harney Valley ranch country near Burns relating the natural and human history of the area. The town of Fort Rock has a museum with several pioneer-days buildings that have good potential for ghost town-like photographs. Hours and access are SOUTHEAST OREGON limited so you can’t get the best angles during the golden hours, but it is possible to make some nice images from the parking area at those times. -

Eastern Oregon University Conditions Report

APRIL 2018 EASTERN OREGON UNIVERSITY (EOU) CONDITIONS REPORT Related to State Board of Higher Education Conditions, 2014 BACKGROUND AND SUMMARY OF FINDINGS When the Oregon Legislature created a pathway for Oregon’s technical and regional universities (Oregon Tech, Western Oregon University, Southern Oregon University, and Eastern Oregon University) to establish institutional governing boards in 2014, it authorized the former State Board of Higher Education (SBHE) and the Governor to establish “Conditions” that any independence-seeking technical and regional institution would be expected to meet during its initial years of operation under its new board. The law1 establishes that the Higher Education Coordinating Commission (HECC) must ultimately determine whether the institutions have been satisfied, and must notify the Governor, the Board of Trustees of the institution, and the Legislature of its finding. Based on longstanding concerns about the fragility of Eastern Oregon University (EOU) and Southern Oregon University (SOU), the SBHE and Governor agreed in 2014 to a specific set of Conditions (linked to here), and a timeframe for meeting them, for both institutions. Under the SBHE- and Governor-adopted Conditions, EOU was required to submit to the HECC a comprehensive report demonstrating the institution’s unique mission, program focus, and long-term financial viability. The Commission is required to evaluate whether the institution meets the conditions by demonstrating a clear institutional focus and durable niche within the portfolio of public higher education assets in Oregon, and determining that this niche: Supports the state’s and region’s civic, cultural, economic and 40-40-20 needs; Enables a cohesive and sustainable enrollment model; and Supports the long-term viability of the institution. -

Eastern Oregon

55 Eastern Oregon Oregon State University Extension Service Special Report 371 October 1972 Cooperath e Extension work in Agriculture and Home Economics, Lee Kolmer, director. Printed and distributed in furtherance of Acts of Congress of May 8 and June 30, 1914. Oregon State University and the J. S. Department of Agriculture, cooperating. EASTERN OREGON WINDBREAK TREES AND SHRUBS Observations of Various Species Over a Period of 22 Years by Charles R. Ross Forestry Extension School of Forestry - Cooperative Extension Service Oregon State University 1946-1969 INTRODUCTION For twenty-two years, I observed trees and shrubs planted for wind- breaks in eastern Oregon. In this paper some conclusions are drawn, although I will be the first to emphasize that the knowledge we need and do not have would fill a much more extensive report. My observations and field work in eastern Oregon were occasional rather than continuous. An effort was made to study the results of research and to consult with other workers, especially those in Washington and Idaho. A paper frequently referred to is the March, 1965, Station Circular 450, a publication of the WSU Agricultural Station entitled "Adaptation Tests of Trees and Shrubs for the Intermountain Areas of the Pacific Northwest." The experiences of Extension Agents and other field men were drawn upon, as was a 1967 report of the Windbreaks Committee in Washington State. CONIFERS FOR WINDBREAKS AND SHADE TREES General Comments. For 22 years, I observed certain species of evergreens, or conifers, planted as windbreaks in eastern Oregon. Of the species ob- served, ponderosa pine, Rocky Mountain juniper, Virginia juniper, and Aus- trian pine would be rated as generally good performers. -

Restoring Ea Ste Rn O Re Gon's D Ry Forests

Restoring eastern Oregon’s dry forests: A practical guide for ecological restoration by Tim Lillebo, Oregon Wild Restoring eastern Oregon’s dry forests: A practical guide for ecological restoration by Tim Lillebo Dry ponderosa pine forests are used by deer and other wildlife. (Brett Cole) A publication of Oregon Wild (www.oregonwild.org), dedicated to protecting and restor- ing Oregon’s wildlands, wildlife, and waters as an enduring legacy for future generations. This work was made possible by the generous support of The Collins Foundation and The Stubbeman Family Foundation and is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License. © 2012 Printed on 100% recycled paper made from 50% post-consumer waste with soy-based inks. Compiled by Chandra LeGue Design and layout by Joanna deFelice Cover photo: Prescribed fire is used to manage dry eastern Oregon forests. (Brett Cole) i Contents Introduction . ii Current conditions in eastern Oregon forests. .. 1 Prioritizing restoration . .. 2 A restoration vision for eastern Oregon . .. 3 The Glaze Forest restoration project: a case study Past management and history. .. 4 Collaboration as a restoration tool . 6 Restoration concepts and prescriptions Where and why to apply these prescriptions . .. 7 Four steps to restoration Step 1: Design comprehensive restoration goals . 8 Step 2: Apply principles for forest restoration . 8 Step 3: Lay out the treatment prescription . 9 Step 4: Implement prescriptions and monitor results . 9 Lessons for successful ecological forest restoration . 11 Minimizing unintended impacts . 12 Resources . .. 14 Glossary . .. 15 About the author . .. 16 Acknowledgements . inside back cover A healthy aspen stand mixed with ponderosa pines.