Sport & Entertainment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Difference-Based Analysis of the Impact of Observed Game Parameters on the Final Score at the FIBA Eurobasket Women 2019

Original Article Difference-based analysis of the impact of observed game parameters on the final score at the FIBA Eurobasket Women 2019 SLOBODAN SIMOVIĆ1 , JASMIN KOMIĆ2, BOJAN GUZINA1, ZORAN PAJIĆ3, TAMARA KARALIĆ1, GORAN PAŠIĆ1 1Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, University of Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina 2Faculty of Economy, University of Banja Luka, Bosnia and Herzegovina 3Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, University of Belgrade, Serbia ABSTRACT Evaluation in women's basketball is keeping up with developments in evaluation in men’s basketball, and although the number of studies in women's basketball has seen a positive trend in the past decade, it is still at a low level. This paper observed 38 games and sixteen variables of standard efficiency during the FIBA EuroBasket Women 2019. Two regression models were obtained, a set of relative percentage and relative rating variables, which are used in the NBA league, where the dependent variable was the number of points scored. The obtained results show that in the first model, the difference between winning and losing teams was made by three variables: true shooting percentage, turnover percentage of inefficiency and efficiency percentage of defensive rebounds, which explain 97.3%, while for the second model, the distinguishing variables was offensive efficiency, explaining for 96.1% of the observed phenomenon. There is a continuity of the obtained results with the previous championship, played in 2017. Of all the technical elements of basketball, it is still the shots made, assists and defensive rebounds that have the most significant impact on the final score in European women’s basketball. -

Evaluating Lineups and Complementary Play Styles in the NBA

Evaluating Lineups and Complementary Play Styles in the NBA The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:38811515 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Data 13 3 Methods 20 3.1 Model Setup ................................. 21 3.2 Building Player Proles Representative of Play Style . 24 3.3 Finding Latent Features via Dimensionality Reduction . 30 3.4 Predicting Point Diferential Based on Lineup Composition . 32 3.5 Model Selection ............................... 34 4 Results 36 4.1 Exploring the Data: Cluster Analysis .................... 36 4.2 Cross-Validation Results .......................... 42 4.3 Comparison to Baseline Model ....................... 44 4.4 Player Ratings ................................ 46 4.5 Lineup Ratings ............................... 51 4.6 Matchups Between Starting Lineups .................... 54 5 Conclusion 58 Appendix A Code 62 References 65 iv Acknowledgments As I complete this thesis, I cannot imagine having completed it without the guidance of my thesis advisor, Kevin Rader; I am very lucky to have had a thesis advisor who is as interested and knowledgable in the eld of sports analytics as he is. Additionally, I sincerely thank my family, friends, and roommates, whose love and support throughout my thesis- writing experience have kept me going. v Analytics don’t work at all. It’s just some crap that people who were really smart made up to try to get in the game because they had no talent. -

PJ Savoy Complete

PJ SAVOY 6-4/210 GUARD LAS VEGAS, NEVADA CHAPARRAL HIGH SCHOOL (CHANCELLOR DAVIS) LAS VEGAS HIGH SCHOOL (JASON WILSON) SHERIDAN COLLEGE (MATT HAMMER) FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY (LEONARD HAMILTON) PJ Savoy’s Career Statistics Year G-GS FG-A PCT. 3FG-3FGA PCT. FT-FTA PCT. PTS.-AVG. OR DR TR-AVG. PF-D AST TO BLK STL MIN 2016-17 28-0 47-114 .412 40-100 .400 21-30 .700 155-5.5 4 19 23-0.8 15-0 7 9 1 10 228-8.1 2017-18 27-4 58-158 .367 50-135 .370 16-22 .727 182-6.7 5 33 38-1.4 28-0 15 17 1 6 355-13.1 2018-19 37-18 68-187 .364 52-158 .329 32-39 .821 220-5.9 7 37 44-1.2 44-0 18 30 4 17 542-14.6 Totals 92-22 173-459 .381 142-393 .366 69-91 .749 557-6.03 16 89 105-1.1 87-0 40 56 6 33 1125-25.2 PJ Savoy’s Conference Statistics Year G-GS FG-A PCT. 3FG-3FGA PCT. FT-FTA PCT. PTS.-AVG. OR DR TR-AVG. PF-D AST TO BLK STL MIN 2016-17 17-0 27-63 .429 21-54 .389 10-15 .667 85-5.0 4 15 19-1.1 6-0 2 5 1 6 279-15.5 2017-18 11-1 20-56 .357 18-51 .353 8-11 .727 66-6.0 2 7 9-0.8 11-0 7 7 0 1 147-13.4 2018-19 18-5 30-85 .353 24-74 .324 13-15 .867 97-5.4 3 14 17-0.9 21-0 5 11 1 9 218-12.1 Totals 46-6 77-204 .378 63-179 .352 31-41 .756 248-5.4 9 36 45-1 38-0 14 23 2 16 644-14.0 PJ Savoy’s NCAA Tournament Statistics Year G-GS FG-A PCT. -

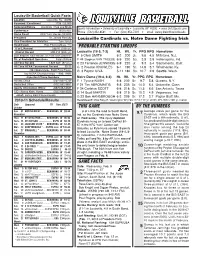

Probable Starting Lineups This Game by the Numbers

Louisville Basketball Quick Facts Location Louisville, Ky. 40292 Founded / Enrollment 1798 / 22,000 Nickname/Colors Cardinals / Red and Black Sports Information University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 www.UofLSports.com Conference BIG EAST Phone: (502) 852-6581 Fax: (502) 852-7401 email: [email protected] Home Court KFC Yum! Center (22,000) President Dr. James Ramsey Louisville Cardinals vs. Notre Dame Fighting Irish Vice President for Athletics Tom Jurich Head Coach Rick Pitino (UMass '74) U of L Record 238-91 (10th yr.) PROBABLE STARTING LINEUPS Overall Record 590-215 (25th yr.) Louisville (18-5, 7-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Asst. Coaches Steve Masiello,Tim Fuller, Mark Lieberman F 5 Chris SMITH 6-2 200 Jr. 9.8 4.5 Millstone, N.J. Dir. of Basketball Operations Ralph Willard F 44 Stephan VAN TREESE 6-9 220 So. 3.5 3.9 Indianapolis, Ind. All-Time Record 1,625-849 (97 yrs.) C 23 Terrence JENNINGS 6-9 220 Jr. 9.3 5.4 Sacramento, Calif. All-Time NCAA Tournament Record 60-38 G 2 Preston KNOWLES 6-1 190 Sr. 14.9 3.7 Winchester, Ky. (36 Appearances, Eight Final Fours, G 3 Peyton SIVA 5-11 180 So. 10.7 2.9 Seattle, Wash. Two NCAA Championships - 1980, 1986) Important Phone Numbers Notre Dame (19-4, 8-3) Ht. Wt. Yr. PPG RPG Hometown Athletic Office (502) 852-5732 F 1 Tyrone NASH 6-8 232 Sr. 9.7 5.8 Queens, N.Y. Basketball Office (502) 852-6651 F 21 Tim ABROMAITIS 6-8 235 Sr. -

Ranking the Greatest NBA Players: an Analytics Analysis

1 Ranking the Greatest NBA Players: An Analytics Analysis An Honors Thesis by Jeremy Mertz Thesis Advisor Dr. Lawrence Judge Ball State University Muncie, Indiana July 2015 Expected Date of Graduation May 2015 1-' ,II L II/du, t,- i II/em' /.. 2 ?t; q ·7t./ 2 (11 S Ranking the Greatest NBA Players: An Analytics Analysis . Iv/If 7 Abstract The purpose of this investigation was to present a statistical model to help rank top National Basketball Association (NBA) players of all time. As the sport of basketball evolves, the debate on who is the greatest player of all-time in the NBA never seems to reach consensus. This ongoing debate can sometimes become emotional and personal, leading to arguments and in extreme cases resulting in violence and subsequent arrest. Creating a statistical model to rank players may also help coaches determine important variables for player development and aid in future approaches to the game via key data-driven performance indicators. However, computing this type of model is extremely difficult due to the many individual player statistics and achievements to consider, as well as the impact of changes to the game over time on individual player performance analysis. This study used linear regression to create an accurate model for the top 150 player rankings. The variables computed included: points per game, rebounds per game, assists per game, win shares per 48 minutes, and number ofNBA championships won. The results revealed that points per game, rebounds per game, assists per game, and NBA championships were all necessary for an accurate model and win shares per 48 minutes were not significant. -

An Analysis of the Contract Year Phenomenon in the NBA: Do Players Perform Better Or Worse Tyler Gaffaney Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2013 An Analysis of the Contract Year Phenomenon in the NBA: Do Players Perform Better or Worse Tyler Gaffaney Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Gaffaney, Tyler, "An Analysis of the Contract Year Phenomenon in the NBA: Do Players Perform Better or Worse" (2013). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 768. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/768 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE An Analysis of the Contract Year Phenomenon in the NBA: Do Players Perform Better or Worse? SUBMITTED TO Professor Ricardo Fernholz AND Dean Nicholas Warner BY Tyler Gaffaney for SENIOR THESIS Fall 2013 December 2, 2013 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank anyone who contributed to this thesis in any way. I would also like to thank my family, especially my parents for their support over the years. Specifically, I would like to thank my reader Professor Ricardo Fernholz for his keen insight and continued advice. Without his help, this thesis would not have been possible. i Abstract The present study uses a novel measure of over performance (percent deviation from career average) to analyze the contract year phenomenon in the NBA. Historically, the literature has pointed toward over performance across almost all statistical measures of performance. However, previous research has assumed that all players are universally affected by the presence of a contract year in the same manner. -

Measuring Production and Predicting Outcomes in the National Basketball Association

Measuring Production and Predicting Outcomes in the National Basketball Association Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael Steven Milano, M.S. Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Packianathan Chelladurai, Advisor Brian Turner Sarah Fields Stephen Cosslett Copyright by Michael Steven Milano 2011 Abstract Building on the research of Loeffelholz, Bednar and Bauer (2009), the current study analyzed the relationship between previously compiled team performance measures and the outcome of an “un-played” game. While past studies have relied solely on statistics traditionally found in a box score, this study included scheduling fatigue and team depth. Multiple models were constructed in which the performance statistics of the competing teams were operationalized in different ways. Absolute models consisted of performance measures as unmodified traditional box score statistics. Relative models defined performance measures as a series of ratios, which compared a team‟s statistics to its opponents‟ statistics. Possession models included possessions as an indicator of pace, and offensive rating and defensive rating as composite measures of efficiency. Play models were composed of offensive plays and defensive plays as measures of pace, and offensive points-per-play and defensive points-per-play as indicators of efficiency. Under each of the above general models, additional models were created to include streak variables, which averaged performance measures only over the previous five games, as well as logarithmic variables. Game outcomes were operationalized and analyzed in two distinct manners - score differential and game winner. -

Stonehill (15-4/9-4 NE-10) Saturday - January 29, 2011 - 3:30 Pm Merkert Gymnasium (2,200) Easton, Massachusetts

2010-11 SAINT ROSE MEN'S BASKETBALL MEDIA NOTES Saint Rose (13-6/8-6 NE-10) at Stonehill (15-4/9-4 NE-10) Saturday - January 29, 2011 - 3:30 pm Merkert Gymnasium (2,200) Easton, Massachusetts Game Day Quick Facts Saint Rose "Golden Knights" Probable Starters Series Record: Saint Rose 8-7 F #22 . Brian Hanuschak .... 6-7 ...... JR ... 10.5 ppg ..... 8.8 rpg ........ 1.21 bpg Record at Stonehill: Stonehill 4-3 F #33 . Sheldon Griffin ....... 6-5 ...... JR ... 7.5 ppg ....... 5.1 rpg ........ .851 FT% (57-67) Record at Saint Rose: Saint Rose 5-3 G #1 ... Andre Pope ............. 5-10 .... SO .. 13.2 ppg ..... 4.6 rpg ........ 4.11 apg ......... 2.00 spg Neutral Courts: N/A G #10 . Shea Bromirski ....... 6-0 ...... JR ... 15.3 ppg ..... 2.89 apg ..... .889 FT% (80-90) NCAA Tournament: Saint Rose 1-0 G #11 . Rob Gutierrez ......... 6-0 ...... JR ... 18.5 ppg ..... 4.4 rpg ........ 2.00 spg First Meeting: 3/8/98 at Siena ....... Saint Rose 97-87 (2OT) Off The Bench ....... NCAA Regional Championship C #52 . Dominykas Milka.... 6-8 ...... FR... 5.6 ppg ....... 4.4 rpg ........ 15.4 minutes Largest Saint Rose Win: 1/18/03 G #3 ... Kareem Thomas ..... 6-1 ...... FR... 4.9 ppg ....... 1.06 apg ..... 15.6 minutes ....... 103-73 at Saint Rose F #50 . Devin Grimes ......... 6-6 ...... SO .. 3.9 ppg ....... 3.8 rpg ........ 14.0 minutes Largest Stonehill Win: 2/21/09 ....... 80-59 at Stonehill Audio Broadcast - Via the Web: ....... www.gogoldenknights.com Stonehill "Skyhawks" Probable Starters ..... -

06-07 Boys Basketball

Boy's Basketball GAME SEASON Most Points—Chester Lawrence (51) 65-66 Points—Chester Lawrence (781) 65-66 Rebounds—Travis Jones (19) 96-97 Rebounds—Mike Zimmers (318) 66-67 Assists-Lucas Hook (16) 92-93 Assists—Lucas Hook (160) 93-94 Field Goals Made—(23/28) 12/12/98 Massac Co. Field Goals Attempted—Chester Lawrence (560) 65-66 Steals-Adam Schneider (8) 98-99 12/11/98 Field Goals Made—Chester Lawrence (295) 65-66 Free Throws Made—Adam Hook (13 of 16) 98-99 Free Throws Attempted—Donnie Brady (282) 3 Point Shots Made—Drew Lawrence (8) 12/18/98, Garrett Davis (8) 04-05 Free Throws Made—Donnie Brady (205) Blocked Shots- Brett Thompson (16) 04-05 Free Throw Percentage—Bryan Waters (82.5%) 03-04 Points Per Game Average—Chester Lawrence (28.9) 65-66 CAREER Field Goal Percentage--Darin Shoemaker (69.39%) Total Points—Chester Lawrence (1897) 63-66 Charges Drawn-Jared Gurley (22) 01-02 Rebounds-Chris Geisler (751) 93-96 Steals—Bob Trover (94) 71-74 Assists-Lucas Hook (347) 91-94 Assists-Lucas Hook (160) 93-94 Steals-Bob Trover (249) 71-74 Three Pointers Made-Garrett Davis (60) 04-05 Field Goals-Chester Lawrence (?) 63-66 Blocked Shots-Brett Thompson (74) 04-05 Free Throws— 3 Point Shots Made-Brandon Bundren (126) 00-03 TEAM RECORDS-GAME Points 65-66 (121) TEAM RECORDS-SEASON Field Goals Made-(49) 73-74 Wins-(24) 65-66 & 72-73 & 74-75 & 05-06 Free Throws Made— High Average-(90.8) 65-66 3 Point Shots Made (11) 94-95 (11) 04-05 Defensive Average-(52.0) 93-94 & (52.4) 04-05 Most Points Average (90.8) 65-66 Winning %-(96%) 24-1 72-73 Least Points Allowed -

NCAA Men's Basketball Direction of the Game Update

MEMORANDUM January 15, 2019 VIA EMAIL To: Men’s Basketball Conference Commissioners, Directors of Athletics, Head Coaches and Registered Officials. From: Tad Boyle, Chair NCAA Men’s Basketball Rules Committee Jeff Hathaway, Chair NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Oversight Committee Jim Delany, Chair NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Competition Committee. SUBJECT: NCAA Men’s Basketball Direction of the Game Update. Following the 2014-15 season, the NCAA Men’s Basketball Rules Committee and NCAA Division I Men’s Basketball Oversight Committee began a review to identify potential rules changes and officiating initiatives to improve the pace of play, better balance offense with defense and reduce the physicality in the sport. The goal of the changes was to keep men’s college basketball competitive, contemporary, fair and moving towards an even more appealing game for student-athletes, coaches and fans. One of the moving forces behind the desire to review the rules and the enforcement of the rules stemmed from the analysis of certain data obtained from men’s basketball games. For instance, NCAA men’s Division I basketball teams averaged 76 points per game during the 1990-91 season. Over the course of the next 25 years, the per game average slowly, but steadily, dropped by nine points to 67 points per game during the 2014-15 season, the lowest since the 1980-81 season. During the same time period, increasingly physical play was permitted evidenced by the lowest fouls per game average and the lowest field goal percentage rates in decades. In an attempt to reverse these alarming trends in our game, the rules committee adopted several changes including: 1. -

Detroit Pistons Game Notes | @Pistons PR

Date Opponent W/L Score Dec. 23 at Minnesota L 101-111 Dec. 26 vs. Cleveland L 119-128(2OT) Dec. 28 at Atlanta L 120-128 Dec. 29 vs. Golden State L 106-116 Jan. 1 vs. Boston W 96 -93 Jan. 3 vs.\\ Boston L 120-122 GAME NOTES Jan. 4 at Milwaukee L 115-125 Jan. 6 at Milwaukee L 115-130 DETROIT PISTONS 2020-21 SEASON GAME NOTES Jan. 8 vs. Phoenix W 110-105(OT) Jan. 10 vs. Utah L 86 -96 Jan. 13 vs. Milwaukee L 101-110 REGULAR SEASON RECORD: 20-52 Jan. 16 at Miami W 120-100 Jan. 18 at Miami L 107-113 Jan. 20 at Atlanta L 115-123(OT) POSTSEASON: DID NOT QUALIFY Jan. 22 vs. Houston L 102-103 Jan. 23 vs. Philadelphia L 110-1 14 LAST GAME STARTERS Jan. 25 vs. Philadelphia W 119- 104 Jan. 27 at Cleveland L 107-122 POS. PLAYERS 2020-21 REGULAR SEASON AVERAGES Jan. 28 vs. L.A. Lakers W 107-92 11.5 Pts 5.2 Rebs 1.9 Asts 0.8 Stls 23.4 Min Jan. 30 at Golden State L 91-118 Feb. 2 at Utah L 105-117 #6 Hamidou Diallo LAST GAME: 15 points, five rebounds, two assists in 30 minutes vs. Feb. 5 at Phoenix L 92-109 F Ht: 6 -5 Wt: 202 Averages: MIA (5/16)…31 games with 10+ points on year. Feb. 6 at L.A. Lakers L 129-135 (2OT) Kentucky NOTE: Scored 10+ pts in 31 games, 20+ pts in four games this season, Feb. -

MEN's BASKETBALL INFORMATION 24 Micaiah Abii Fr

MEN’S BASKETBALL 2020-21 GAME NOTES Steven Gonzalez, Associate Director for Communications · Cell: (602) 803-0521 · E-mail: [email protected] LIBERTY MISSISSIPPI STATE FLAMES V BULLDOGS 2020 -21 SCHEDULE & RESULTS 0-1 OVERALL S 0-1 OVERALL OVERALL RECORD: 0-1 0-0 ASUN 0-0 SEC ASUN: 0-0 | Non-Conference: 0-1 THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 26 | 6 P.M. ET | TITAN FIELD HOUSE | MELBOURNE, FLA. Home: 0-0 | Away: 0-0 | Neutral: 0-1 COACHING MATCHUP THE STARTING 5 - LIBERTY'S TOP STORYLINES NOVEMBER • Micaiah Abii's 19 points is the most in a Liberty 25 vs. Purdue^ L, 64-77 LIBERTY MISS. ST. freshman debut since Seth Curry (23 points) in 2008. 26 vs. Clemson/Mississippi State^ 6 P.M. Ritchie Ben Head Coach • Coach McKay is 3-2 all-time against Ben Howland, as 28 vs. South Carolina $ 4 P.M. McKay Howland the two met while McKay was at Portland State and Howland was the head coach at Northern Arizona. 29 vs. TCU/Tulsa $ TBD 154-88 Record at School 98-68 DECEMBER (8) (Years) (5) • Liberty last met Mississippi State in the 2019 NCAA Tournament (Liberty won 80-76). 3 ST. FRANCIS (PA.) 7 P.M. 319-246 499-274 Overall Record • Liberty has played in three straight conference 5 BLUEFIELD COLLEGE 2 P.M. (19) (Years) (24) championship games (Big South in 2018) and back- 9 at Missouri 8 P.M. to-back ASUN Conference Championship SERIES HISTORY VS. MISSISSIPPI ST. appearances. 15 SOUTH CAROLINA STATE 7 P.M. 1-1 • Ritchie McKay is the reigning NABC District 3 Coach 17 REGENT 7 P.M.