The Politics of Us Oil Pipelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanical Engineering Magazine

BIG INCH PIPELINE LITTLE BIG INCH PIPELINE STORAGE TANKS PUMPING STATIONS PIPELINES Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/memagazineselect/article-pdf/138/07/40/6359862/me-2016-jul3.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 FOR WAR AND PEACE BY FRANK WICKS These 24-inch pipes were stacked and ready to be assembled into the Big Inch Pipeline, in this 1942 image from the U.S. Farm Security Administration. Photographer John Vachon took this photo in Pennsylvania. MECHANICAL ENGINEERING | JULY 2016 | P.41 orld War II was largely about oil, Downloaded from http://asmedigitalcollection.asme.org/memagazineselect/article-pdf/138/07/40/6359862/me-2016-jul3.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 and fought with oil. The United States factories and work force, largely idled by the lingering Great Depression, would convert Wto the massive production of land vehicles, ships, and aircraft. These war machines were trans- ported to combat zones, but would be worthless without oil. Of the seven billion barrels of oil used by the Allies, 80 percent came from the United States, mostly from Texas and the Gulf Coast. Prior to the war, much of the crude oil and refi ned products had been transported by coastal tank- ers to the northeast and then shipped across the Atlantic. War started raging in Europe in 1939. The United States remained offi cially neutral until the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December They wouldn’t be the country’s fi rst pipelines, The tanker 1941. but they would be the largest. Building them Dixie Arrow was torpedoed off Cape When Hitler declared war on the United States would be the largest joint government and private Hatteras in March a few days later, he gave Germany free rein for industry project to that time. -

Facts About Alberta's Oil Sands and Its Industry

Facts about Alberta’s oil sands and its industry CONTENTS Oil Sands Discovery Centre Facts 1 Oil Sands Overview 3 Alberta’s Vast Resource The biggest known oil reserve in the world! 5 Geology Why does Alberta have oil sands? 7 Oil Sands 8 The Basics of Bitumen 10 Oil Sands Pioneers 12 Mighty Mining Machines 15 Cyrus the Bucketwheel Excavator 1303 20 Surface Mining Extraction 22 Upgrading 25 Pipelines 29 Environmental Protection 32 In situ Technology 36 Glossary 40 Oil Sands Projects in the Athabasca Oil Sands 44 Oil Sands Resources 48 OIL SANDS DISCOVERY CENTRE www.oilsandsdiscovery.com OIL SANDS DISCOVERY CENTRE FACTS Official Name Oil Sands Discovery Centre Vision Sharing the Oil Sands Experience Architects Wayne H. Wright Architects Ltd. Owner Government of Alberta Minister The Honourable Lindsay Blackett Minister of Culture and Community Spirit Location 7 hectares, at the corner of MacKenzie Boulevard and Highway 63 in Fort McMurray, Alberta Building Size Approximately 27,000 square feet, or 2,300 square metres Estimated Cost 9 million dollars Construction December 1983 – December 1984 Opening Date September 6, 1985 Updated Exhibit Gallery opened in September 2002 Facilities Dr. Karl A. Clark Exhibit Hall, administrative area, children’s activity/education centre, Robert Fitzsimmons Theatre, mini theatre, gift shop, meeting rooms, reference room, public washrooms, outdoor J. Howard Pew Industrial Equipment Garden, and Cyrus Bucketwheel Exhibit. Staffing Supervisor, Head of Marketing and Programs, Senior Interpreter, two full-time Interpreters, administrative support, receptionists/ cashiers, seasonal interpreters, and volunteers. Associated Projects Bitumount Historic Site Programs Oil Extraction demonstrations, Quest for Energy movie, Paydirt film, Historic Abasand Walking Tour (summer), special events, self-guided tours of the Exhibit Hall. -

Recent Federal Regulation of the Petroleum Pipe Line As a Common Carrier Theodore L

Cornell Law Review Volume 32 Article 2 Issue 3 March 1947 Recent Federal Regulation of the Petroleum Pipe Line as a Common Carrier Theodore L. Whitesel Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Theodore L. Whitesel, Recent Federal Regulation of the Petroleum Pipe Line as a Common Carrier , 32 Cornell L. Rev. 337 (1947) Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol32/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RECENT FEDERAL REGULATION OF THE PETRO- LEUM PIPE LINE AS A COMMON CARRIER THEODORE L. WHITESEL Jurisdiction Under the Interstate Commerce Act Regulation of the interstate petroleum pipe line as a common carrier under the Interstate Commerce Act has had as its major purpose the achievement of competition among shippers in the petroleum industry It is the object of this survey to examine the recent attempts at regulation to see if this purpose has been achieved' and to set forth the legal and economic factors entering into the problem of regulation. The groups that favor petroleum pipe line regulation to maintain com- petition are the consumers of refined petroleum products, the independent refiners of crude oil, the independent jobbers of refined petroleum products, the independent service station dealers, the competitive carriers of petroleum, lt might well be the objective of a study to appraise the economic merits of com- petitive organization of the oil industry as compared to monopolistic organization under government control,-backgrounded against the national welfare and the national de- fense. -

Frackonomics: Some Economics of Hydraulic Fracturing

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 63 Issue 4 Article 13 2013 Frackonomics: Some Economics of Hydraulic Fracturing Timothy Fitzgerald Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Timothy Fitzgerald, Frackonomics: Some Economics of Hydraulic Fracturing, 63 Case W. Rsrv. L. Rev. 1337 (2013) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol63/iss4/13 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. Case Western Reserve Law Review·Volume 63 ·Issue 4·2013 Frackonomics: Some Economics of Hydraulic Fracturing Timothy Fitzgerald † Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 1337 I. Hydraulic Fracturing ...................................................................... 1339 A. Microfracture-onomics ...................................................................... 1342 B. Macrofrackonomics ........................................................................... 1344 1. Reserves ....................................................................................... 1345 2. Production ................................................................................... 1348 3. Prices .......................................................................................... -

Advantages, Disadvantages and Economic Benefits Associated with Crude Oil Transportation

Issue Brief 2 02/20/2015 Advantages, Disadvantages and Economic Benefits Associated with Crude Oil Transportation Overview Oil production is an important source of energy, employment, and government revenue in the United States and Canada. Production of crude oil is undergoing a boom in North America due to development of unconventional1 crude sources, including the Alberta oil sands and several geologic shale plays, primarily the Bakken fields in North Dakota and Montana, in addition to the Permian and Eagle Ford fields in Texas. In recent years, domestic production of crude oil in the United States has increased at tremendous rates and is predicted to continue this trend, with total production reaching an estimated 7.4 million barrels per day (bbl/d) in 2013, up from 5.35 million bbl/d five years prior in 2009.2 The forecasted output for 2015 (9.3 million bbl/d) represents what will be the highest levels of domestic production in the United States since 1972.3 This production is coupled with a decline of crude oil imports, with the share of total U.S. liquid fuels consumption met by net imports hitting a low of 33 percent in 2013, down from 60 percent in 2005.4 Canadian crude oil production has also increased dramatically with 3.3 million bb/d produced in 2013, up from 2.57 million bbl/d in 2009.5 As the primary source of imported crude oil to the United States, the Canadian and U.S. oil economies are tightly linked despite declining U.S. imports.6 The rise in crude oil production has accelerated industry demand for transportation to move crude oil from extraction locations to refineries in both nations. -

Interstate Pipelines a Plan for a New New York

LARRY SHARPE FOR NEW YORK Interstate Pipelines A Plan for a New New York Prepared for: Larry Sharpe for NY Governor Prepared by: Russ Clark, Deputy Policy Director, Larry Sharpe for New York May 28, 2018 Proposal number: IF-0002 LARRY SHARPE FOR NEW YORK EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Objective To provide a path forward for natural gas and petroleum pipelines in New York. Goals 1) Reduce the cost of energy in New York. 2) Protect land values and encourage co-location of pipelines with other energy corridors. 3) Provide jobs and economic development while reducing the need to import energy from other states. 4) Prevent shortfalls in electric energy supply for both NYISO and NEISO. Background 1) Upon entering World War II, Nazi submarines sunk petroleum fuel and crude oil barges headed for Philadelphia and New York. According to historian Keith Miller, “They were highly effective and many Caribbean island beaches were seriously polluted with oil,”. In response, the United States government commissioned the construction of two pipelines from Texas to Pennsylvania and New York to support the war effort and provide export terminals to supply European allies with fuel. The pipelines were privatized and converted to natural gas service following the conclusion of the war (“Big Inch Pipelines of WWII”, American Oil and Gas Historical Society). Today, New York imports much of its natural gas supply from other states, including Pennsylvania, Texas and Louisiana, which is supplemented by additional imports from Canada via the Iroquois pipeline. (Energy Information Agency, 2018) 2) Following several pricing and supply crises in the late 1970’s, Congress passed the Natural Gas Policy Act in 1978. -

The Costs of CO2 Transport

The Costs of CO2 Transport Post-demonstration CCS in the EU This document has been prepared on behalf of the Advisory Council of the European Technology Platform for Zero Emission Fossil Fuel Power Plants. The information and views contained in this document are the collective view of the Advisory Council and not of individual members, or of the European Commission. Neither the Advisory Council, the European Commission, nor any person acting on their behalf, is responsible for the use that might be made of the information contained in this publication. 2 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................5 1 Study on CO2 Transport Costs ................................................................................................................8 1.1 Background .....................................................................................................................................8 1.2 Use of new, in-house data ..............................................................................................................8 1.3 Literature and references ................................................................................................................9 1.4 Reader’s guide to the report .............................................................................................................10 2 General CCS Assumptions....................................................................................................................11 -

Ensuring the Reliability of Pipeline Transport in Gas Projects in Uzbekistan

92 ABOUT SUSTAINABILITY CLIMATE ENVIRONMENTAL INDUSTRIAL SAFETY HR LOCAL THE COMPANY STRATEGY CHANGE PROTECTION AND HEALTH MANAGEMENT COMMUNITIES PROTECTION ENSURING THE RELIABILITY OF PIPELINE TRANSPORT IN GAS PROJECTS IN UZBEKISTAN Pipeline Transport Safety Improvement Practical experience in operating the Advanced corrosion monitoring methods Program does not apply to foreign Khauzak-Shady and Gissar fields has (FSM matrix, Ultracorr, Hydrosteel 6000) oil and gas organizations; however, shown that the approaches used to are used in the fields, and an automated specialists from the Network Group ensure the reliability of pipelines in a very electrochemical protection system is and LUKOIL Group entities work with harsh environment have contributed to being designed. The Wavemaker system colleagues from foreign organizations on trouble-free operation for the past 10 has been installed, which allows an object projects in which LUKOIL is an operator, years. to be monitored at a distance of up to and provide necessary consultations. To ensure the integrity of equipment, 100 meters in both directions from an Gas fields in Uzbekistan are characterized the corporate standards of installed sensor; consequently, diagnoses by having high gas pressure (up to 200 LLC LUKOIL Uzbekistan Operating Company can be performed in hard-to-reach areas. atm), high hydrogen sulfide H2S (up have been elaborated and agreed with There are plans to integrate data on the to 4.5%, Southern Gissar), and carbon the state inspection of the Republic of results of in-line diagnostics with the dioxide (up to 5%) content, as well as Uzbekistan. These standards regulate the geographic information system of LLC high chloride content in formation water procedures for monitoring the technical LUKOIL Uzbekistan Operating Company. -

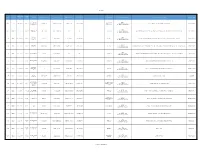

Pre-Job List

Pre Jobs Total On Pre Approx. Pre Job Start Date Contractor Warehouse Location Steward Welder Foreman Welders Phone Gas Company Hours, Wages, & Per Diem Job Description & Welding Test Business Agent Job End 5x10 1X8 LMC Industrial LMC Industrial 14380 TBD W-1 J-1 H-3 10/29/21 Fort Plain, NY Donaldson, Rodney W Fegley, Eric M (315) 651-5944 W&J-43.18 H-23.30 12" meter station work located in Montgomery County, NY David Butterworth Contractors, Inc. Contractors, Inc. W- 150.50 J- 90.50 H- 64.50 5x10 John E. Green 14359 10/4/21 W-1 J-1 H-2 10/15/21 East China, MI Downer, Stephen M N/A N/A Dte Energy W&J-53.97 H-30.83 Meter Installation (Removal of 2-10" temporary spools and installation of 2- owner furnished meters) in East China, MI Charles Yates JR. Company W- 150.50 J- 90.50 H- 64.50 6x10 Minnesota 14361 10/4/21 W-4 J-1 or AN H-5 12/18/21 Kokomo, IN Turner, Robert S Seyler, Justin W (817) 908-8903 Nisource W&J-53.97 H-27.11 Installation of regulator station with various pipe diameters 8", 12", 16", 20", & 24" in Howard Co., Indiana Charles Yates Jr. Limited, Inc. W- 150.50 J- 90.50 H- 64.50 5x10 1x8 Minnesota 14360 10/4/21 W-2 J-AN H-2 10/23/21 Wapakoneta, OH Pattison, Joshua L Schwartz, Cory J (763) 592-9177 Dominion W&J-53.97 H-32.23 Relocation of approx. -

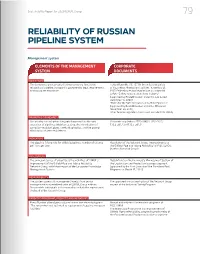

Reliability of Russian Pipeline System

Sustainability Report for 2020 LUKOIL Group 79 RELIABILITY OF RUSSIAN PIPELINE SYSTEM Management system ELEMENTS OF THE MANAGEMENT CORPORATE SYSTEM DOCUMENTS OBJECTIVES The Company’s policy related to improving the functional Federal Law No. 116-FZ “On the Industrial Safety reliability of pipeline transport is governed by legal requirements of Hazardous Production Facilities” dated July 21, and corporate standards 1997, Federal rules and regulations on industrial safety “Safety rules in oil and gas industry” (approved by Rostekhnadzor order No. 534 dated December 15, 2020); “Rules for the Safe Operation of In-Field Pipelines” (approved by Rostekhnadzor order No. 515 dated November 30, 2017); other federal regulations and rules on industrial safety PRIORITIES/STANDARDS Our priority is to adopt an integrated approach to the safe Corporate regulations (STO LUKOIL 1.19.1-2012; operation of pipelines: inhibitor coating, the introduction of 1.19.2-2013 and 1.19.3-2013) corrosion-resistant pipes, timely diagnostics, and the prompt elimination of detected defects INDICATORS The pipeline failure rate for oilfield pipelines, number of failures Resolution of the Network Group “Improvements to per 1 km, per year the Oilfield Pipe and Tubing Reliability” of PJSC LUKOIL (further, Network Group) ASSESSMENT The principal source of expertise is the activities of LUKOIL’s Regulations on the Knowledge Management System of Improvement of the Oilfield Pipe and Tubing Reliability the Exploration and Production business segment Network Group, which forms part of the Corporate Knowledge (approved by the First Executive Vice President Ravil Management System Maganov on March 19, 2014) RESPONSIBILITY The system covers all management levels, from senior The approved annual work plan of the Network Group management to specialized units at LUKOIL Group entities. -

Issues and Trends Surrounding the Movement of Crude Oil in the Great Lakes-St

Issues and Trends Surrounding the Movement of Crude Oil in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Region | 1 (page intentionally left blank) Issues and Trends Surrounding the Movement of Crude Oil in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Region | 2 Table of Contents Issues and Trends Surrounding the Movement of Crude Oil in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Region Acknowledgments ………………………………………………………………………… 4 Executive Summary………………………………………………………………………. 5 Summary Report ……….…………………………………………………………………. 9 o Background o Purpose of the Report o Developments and Responses from Regional Partners to Recent Oil Spills o Key Findings and Observations Appendices…………………………………………..………………………………………. 31 o Appendix 1: Summary of Comments Received o Appendix 2: Action Item from September 9, 2013, GLC Annual Meeting o Appendix 3: Summary of Issue Brief 1: Developments in Crude Oil Extraction and Movement o Appendix 4: Summary of Issue Brief 2: Advantages, Disadvantages, and Economic Benefits Associated with Crude Oil Transportation o Appendix 5: Summary of Issue Brief 3: Risks and Impacts Associated with Crude Oil Transportation o Appendix 6: Summary of Issue Brief 4: Policies, Programs and Regulations Governing the Movement of Oil Full report available at www.glc.org/projects/water-quality/oil-transport/ Issues and Trends Surrounding the Movement of Crude Oil in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Region | 3 Acknowledgments Preparation of the Summary of Issues and Trends Surrounding the Movement of Crude Oil in the Great Lakes-St. Lawrence River Region and the four companion issue briefs required the time and effort of numerous individuals who worked together, shared ideas, edited several drafts and provided encouragement and support to each other throughout the process. -

Addendum to Environmental Review Documents Concerning Exports of Natural Gas from the United States

ADDENDUM TO ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW DOCUMENTS CONCERNING EXPORTS OF NATURAL GAS FROM THE UNITED STATES AUGUST 2014 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY This page intentionally left blank. ADDENDUM TO ENVIRONMENTAL REVIEW DOCUMENTS CONCERNING EXPORTS OF NATURAL GAS FROM THE UNITED STATES August 2014 This page intentionally left blank. Table of Contents List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................... I List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. II List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ...................................................................................................... IV Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 1 Purpose 3 Public Comments 3 Unconventional Natural Gas Production Activities in the United States 4 Water Resources ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Water Quantity 10 Water Quality 13 Construction 13 Drilling 13 Hydraulic Fracturing Fluids 14 Flowback and Produced Waters 18 Conclusions 19 Air Quality ................................................................................................................................................. 20 Regulations 20 Emission Components and