Digital Rights Management from a Consumer's Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Source Software Vs Proprietary Software Sakshi Singh, Madhvik Verma, Naveen Kumar N

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 8, Issue 12, December-2017 735 ISSN 2229-5518 Open Source Software Vs Proprietary Software Sakshi Singh, Madhvik Verma, Naveen Kumar N Abstract— Open Source software are the most revolutionizing concept that has been put forth in the Information Technology spectrum. This new release has raised quite a lot of brows, similar to when the Internet was launched. For a very long time, there has been a tiff going on between the Proprietary software and the open source software and how the open source software are taking over their ancestors. The technical experts often indulge in conversations as to which of the two software is better and why. People also get confused as to which type of software can be listed as Open source. In this paper we aim to emphasize that the open source development cycle has been there in the market for quite some time and has a huge user base now, thus giving it a strong hold in the software market. It has encouraged the use of new strategically placed actions which has in turn made a huge base for open source software systems. On the other hand, many experts also suggest that this is just momentary and it will pass over a period of time whereas the proprietary software are there to stay. This paper gives the understanding and recommendations for both the kind of software thus giving the user a proper understanding of which software is suitable for their use and thus they can make a better choice for their purpose. -

![Arxiv:1812.09167V1 [Quant-Ph] 21 Dec 2018 It with the Tex Typesetting System Being a Prime Example](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6826/arxiv-1812-09167v1-quant-ph-21-dec-2018-it-with-the-tex-typesetting-system-being-a-prime-example-436826.webp)

Arxiv:1812.09167V1 [Quant-Ph] 21 Dec 2018 It with the Tex Typesetting System Being a Prime Example

Open source software in quantum computing Mark Fingerhutha,1, 2 Tomáš Babej,1 and Peter Wittek3, 4, 5, 6 1ProteinQure Inc., Toronto, Canada 2University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, South Africa 3Rotman School of Management, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada 4Creative Destruction Lab, Toronto, Canada 5Vector Institute for Artificial Intelligence, Toronto, Canada 6Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Canada Open source software is becoming crucial in the design and testing of quantum algorithms. Many of the tools are backed by major commercial vendors with the goal to make it easier to develop quantum software: this mirrors how well-funded open machine learning frameworks enabled the development of complex models and their execution on equally complex hardware. We review a wide range of open source software for quantum computing, covering all stages of the quantum toolchain from quantum hardware interfaces through quantum compilers to implementations of quantum algorithms, as well as all quantum computing paradigms, including quantum annealing, and discrete and continuous-variable gate-model quantum computing. The evaluation of each project covers characteristics such as documentation, licence, the choice of programming language, compliance with norms of software engineering, and the culture of the project. We find that while the diversity of projects is mesmerizing, only a few attract external developers and even many commercially backed frameworks have shortcomings in software engineering. Based on these observations, we highlight the best practices that could foster a more active community around quantum computing software that welcomes newcomers to the field, but also ensures high-quality, well-documented code. INTRODUCTION Source code has been developed and shared among enthusiasts since the early 1950s. -

Open Source Licensing Information for Cisco IOS Release 15.4(1)T

Open Source Used In Cisco IOS Release 15.4(1)T Cisco Systems, Inc. www.cisco.com Cisco has more than 200 offices worldwide. Addresses, phone numbers, and fax numbers are listed on the Cisco website at www.cisco.com/go/offices. Text Part Number: 78EE117C99-15140077 Open Source Used In Cisco IOS Release 15.4(1)T 1 This document contains licenses and notices for open source software used in this product. With respect to the free/open source software listed in this document, if you have any questions or wish to receive a copy of any source code to which you may be entitled under the applicable free/open source license(s) (such as the GNU Lesser/General Public License), please contact us at [email protected]. In your requests please include the following reference number 78EE117C99-15140077 Contents 1.1 bzip2 1.0.0 1.1.1 Available under license 1.2 C/C++ BEEP Core 0.2.00 1.2.1 Available under license 1.3 cd9660 8.18 1.3.1 Available under license 1.4 cthrift-without-GPL-code 0.3.14 1.4.1 Available under license 1.5 CUDD: CU Decision Diagram Package v2.4.1 1.5.1 Available under license 1.6 Cyrus SASL 2.1.0 1.6.1 Notifications 1.6.2 Available under license 1.7 DTOA unknown 1.7.1 Available under license 1.8 editline 1.11 1.8.1 Available under license 1.9 Expat XML Parser - Series 1 v1.2 1.9.1 Available under license 1.10 freebsd-tty-headers n/a 1.10.1 Available under license 1.11 ftp.h 4.4BSD? 1.11.1 Available under license 1.12 inflate.c c10p1 1.12.1 Available under license 1.13 iniparser 2.8 Open Source Used In Cisco IOS -

Long-Term Sustainability of Open Source Software Communities Beyond a Fork: a Case Study of Libreoffice Jonas Gamalielsson, Björn Lundell

Long-Term Sustainability of Open Source Software Communities beyond a Fork: A Case Study of LibreOffice Jonas Gamalielsson, Björn Lundell To cite this version: Jonas Gamalielsson, Björn Lundell. Long-Term Sustainability of Open Source Software Communities beyond a Fork: A Case Study of LibreOffice. 8th International Conference on Open Source Systems (OSS), Sep 2012, Hammamet, Tunisia. pp.29-47, 10.1007/978-3-642-33442-9_3. hal-01519071 HAL Id: hal-01519071 https://hal.inria.fr/hal-01519071 Submitted on 5 May 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Long-term Sustainability of Open Source Software Communities beyond a Fork: a Case Study of LibreOffice Jonas Gamalielsson and Björn Lundell University of Skövde, Skövde, Sweden, {jonas.gamalielsson,bjorn.lundell}@his.se Abstract. Many organisations have requirements for long-term sustainable software systems and associated communities. In this paper we consider long- term sustainability of Open Source software communities in Open Source projects involving a fork. There is currently a lack of studies in the literature that address how specific Open Source software communities are affected by a fork. -

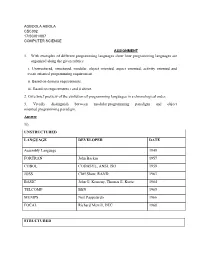

1. with Examples of Different Programming Languages Show How Programming Languages Are Organized Along the Given Rubrics: I

AGBOOLA ABIOLA CSC302 17/SCI01/007 COMPUTER SCIENCE ASSIGNMENT 1. With examples of different programming languages show how programming languages are organized along the given rubrics: i. Unstructured, structured, modular, object oriented, aspect oriented, activity oriented and event oriented programming requirement. ii. Based on domain requirements. iii. Based on requirements i and ii above. 2. Give brief preview of the evolution of programming languages in a chronological order. 3. Vividly distinguish between modular programming paradigm and object oriented programming paradigm. Answer 1i). UNSTRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE Assembly Language 1949 FORTRAN John Backus 1957 COBOL CODASYL, ANSI, ISO 1959 JOSS Cliff Shaw, RAND 1963 BASIC John G. Kemeny, Thomas E. Kurtz 1964 TELCOMP BBN 1965 MUMPS Neil Pappalardo 1966 FOCAL Richard Merrill, DEC 1968 STRUCTURED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL 58 Friedrich L. Bauer, and co. 1958 ALGOL 60 Backus, Bauer and co. 1960 ABC CWI 1980 Ada United States Department of Defence 1980 Accent R NIS 1980 Action! Optimized Systems Software 1983 Alef Phil Winterbottom 1992 DASL Sun Micro-systems Laboratories 1999-2003 MODULAR LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE ALGOL W Niklaus Wirth, Tony Hoare 1966 APL Larry Breed, Dick Lathwell and co. 1966 ALGOL 68 A. Van Wijngaarden and co. 1968 AMOS BASIC FranÇois Lionet anConstantin Stiropoulos 1990 Alice ML Saarland University 2000 Agda Ulf Norell;Catarina coquand(1.0) 2007 Arc Paul Graham, Robert Morris and co. 2008 Bosque Mark Marron 2019 OBJECT-ORIENTED LANGUAGE DEVELOPER DATE C* Thinking Machine 1987 Actor Charles Duff 1988 Aldor Thomas J. Watson Research Center 1990 Amiga E Wouter van Oortmerssen 1993 Action Script Macromedia 1998 BeanShell JCP 1999 AngelScript Andreas Jönsson 2003 Boo Rodrigo B. -

Tilburg University Free and Open Source Software Schellekens, M.H.M

Tilburg University Free and Open Source Software Schellekens, M.H.M. Published in: The Future of the Public Domain Publication date: 2006 Link to publication in Tilburg University Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Schellekens, M. H. M. (2006). Free and Open Source Software: An Answer to Commodification? In L. Guibault, & B. Hugenholtz (Eds.), The Future of the Public Domain: Identifying the Commons in Information Law (pp. 303- 323). (Information Law Series; No. 16). Kluwer Law International. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 27. sep. 2021 Free and open source software: an answer to commodification? Maurice Schellekens 1. Introduction Linux is a PC operating system which is distributed under the General Public License (hereinafter: GPL). The GPL allows for the (royalty-)free use, modification and redistribution of the software. Given these license conditions, Linux users believed they could use the operating system without too many license worries. -

Third-Party Copyright Notices and Licenses

Third-Party Copyright Notices and Licenses For Intel® Omni-Path Software The following is a list of third party licenses that Intel has operated under in the course of producing Intel® Omni-Path Software. BSD 2-clause License ............................................................................................................. 4 RedHat shim ...................................................................................................................... 4 EFI Developer Kit (EDK) ...................................................................................................... 4 EFI Developer Kit II (EDK II) ................................................................................................ 5 BSD 3-clause License ............................................................................................................. 6 Automatically Tuned Linear Algebra Software ......................................................................... 6 chashtable ......................................................................................................................... 6 FreeBSD ............................................................................................................................ 7 HPC Challenge Benchmark ................................................................................................... 7 HyperSQL Database Engine (HSQLDB) ................................................................................... 8 jgraphx ............................................................................................................................ -

Beyond the NDA: Digital Rights Management Isn't Just for Music

Reprinted with permission from the January 2004 issue of the Intellectual Property & Technology Law Journal. Beyond the NDA: Digital Rights Management Isn’t Just for Music By Adam Petravicius and Joseph T. Miotke heft of proprietary information causes companies to lose to a particular project, little regard is given to whether the T billions of dollars each year.1 Yet to compete effective- information is actually needed for the project. ly, companies often must share their most valuable secrets Before sharing its proprietary information, a company with third parties, even their fiercest competitors. should carefully consider the scope of information that needs Companies routinely enter into non-disclosure agreements to be shared. This should be done both at the beginning of (NDAs) when sharing their proprietary information but then each relationship and periodically throughout the relation- forget about them shortly after they are signed, assuming ship. When doing so, a company should not just identify that their information is fully protected by the NDA. general categories of information to be shared but should However, there are a number of steps that companies should identify the specific information in each category. For exam- consider taking to protect their proprietary information after ple, if a company decides to share its customer information, signing an NDA. These steps range from simple steps, such it may not be necessary to disclose customer names; names as marking information appropriately, to sophisticated tech- could be withheld or replaced with random, unique identi- nological solutions, such as using digital rights management fiers. (DRM) software. One factor that should be considered when determining Although a well-drafted NDA provides significant legal which information to share is the scope of protection provid- protection to a company’s proprietary information, the best ed by the relevant NDA. -

OSS Disclosure

Tape Automation Scalar i6000, Firmware Release i11.1 (663Q) Open Source Software Licenses Open Source Software (OSS) Licenses for: Scalar i6000 Firmware Release i11.1 (663Q). The firmware/software contained in the Scalar i6000 is an aggregate of vendor proprietary pro- grams as well as third party programs, including Open Source Software (OSS). Use of OSS is subject to designated license terms and the following OSS license disclosure lists all open source components and their respective, applicable licenses that are part of the tape library firmware. All software that is designated as OSS may be copied, distributed, and/or modified in accordance with the terms and conditions of its respective license(s). Additionally, for some OSS you are entitled to obtain the corresponding OSS source files as required by the respective and applicable license terms. While GNU General Public License ("GPL") and GNU Lesser General Public Li- cense ("LGPL") licensed OSS requires that the sources be made available, Quantum makes all tape library firmware integrated OSS source files, whether licensed as GPL, LGPL or otherwise, available upon request. Please refer to the Scalar i6000 Open Source License CD (part number 3- 01638-xx) when making such request. For contact information, see Getting More Information. LTO tape drives installed in the library may also include OSS components. For a complete list- ing of respective OSS packages and applicable OSS license information included in LTO tape drives, as well as instructions to obtain source files pursuant to applicable license requirements, please reference the Tape Automation disclosure listings under the Open Source Information link at www.quantum.com/support. -

A Graphical Front End for the Julia Programming Language

A Graphical Front End for the Julia Programming Language Stephan Boyer December 2011 1 1 Introduction In order to compete in the landscape of numerical and parallel computing, the Julia Programming Language1 should be easy to use and include plotting functionality. Mathematicians and scientists who are not familiar with SSH and related utilities will find it difficult to command an array of nodes in a computing cluster in the traditional manner. This paper introduces a web-based front end for Julia, which includes a read{evaluate{print loop (REPL) and basic plotting functionality. There are a number of reasons to use a web-based front end: 1. Users do not need to be familiar with UNIX utilities and shell scripting to use Julia on a computing cluster. 2. Users do not need to install special software to use Julia|a web browser is all that is needed. 3. Modern web technologies and standards, such as HTML5, Scalable Vec- tor Graphics (SVG), and AJAX provide a rich platform for generating interactive plots and graphical user interfaces. 4. A front end based on web technologies does not require an Internet connection|the system can always be run locally. 5. A web interface allows for a new social component to numerical and parallel computing. For example, several users could share an interac- tive Julia session, or collaboratively edit a Julia program. 2 The Implementation The current implementation consists of the lighttpd web server, a custom SCGI-based session manager, and a backend written in Julia. Together, these components provide a web-based read{evaluate{print loop (REPL), as shown on the title page. -

White Paper Entitled 'Key Open Source Software for Boosting

MultiSpectra Consultants White Paper Key Open Source Software for Boosting Business Productivity Dr. Amartya Kumar Bhattacharya BCE (Hons.) ( Jadavpur ), MTech ( Civil ) ( IIT Kharagpur ), PhD ( Civil ) ( IIT Kharagpur ), Cert.MTERM ( AIT Bangkok ), CEng(I), FIE, FACCE(I), FISH, FIWRS, FIPHE, FIAH, FAE, MIGS, MIGS – Kolkata Chapter, MIGS – Chennai Chapter, MISTE, MAHI, MISCA, MIAHS, MISTAM, MNSFMFP, MIIBE, MICI, MIEES, MCITP, MISRS, MISRMTT, MAGGS, MCSI, MIAENG, MMBSI, MBMSM Chairman and Managing Director, MultiSpectra Consultants, 23, Biplabi Ambika Chakraborty Sarani, Kolkata – 700029, West Bengal, INDIA. E-mail: [email protected] Website: https://multispectraconsultants.com This paper is being prepared using LibreOffice Writer, an open source software. Businesses are under continuous pressure to cut costs and increase productivity. In modern businesses, computer hardware and software and ancillaries are a major cost factor. It is worthwhile for every business to investigate how best it can leverage the power of open source software to reduce expenses and increase revenues. Businesses that restrict themselves to proprietary software like Microsoft Office get a raw deal. Not only do they have to pay for the software but they have to factor-in the cost incurred in every instance the software becomes corrupt. This includes the fee required to be paid to the computer technician to re-install the software. All this creates a vicious environment where cost and delays keep mounting. It should be a primary aim of every business to develop a system where maintenance becomes automated to the maximum possible extent. This is where open source software like LibreOffice, Apache OpenOffice, Scribus, GIMP, Inkscape, Firefox, Thunderbird, WordPress, VLC media player etc. -

White Paper Entitled 'Using Libreoffice to Increase Business Productivity'

MultıSpectra Consultants Whıte Paper Using LibreOffice to Increase Business Productivity Dr. Amartya Kumar Bhattacharya BCE (Hons.) ( Jadavpur ), MTech ( Civil ) ( IIT Kharagpur ), PhD ( Civil ) ( IIT Kharagpur ), Cert.MTERM ( AIT Bangkok ), CEng(I), FIE, FACCE(I), FISH, FIWRS, FIPHE, FIAH, FAE, MIGS, MIGS – Kolkata Chapter, MIGS – Chennai Chapter, MISTE, MAHI, MISCA, MIAHS, MISTAM, MNSFMFP, MIIBE, MICI, MIEES, MCITP, MISRS, MISRMTT, MAGGS, MCSI, MIAENG, MMBSI, MBMSM Chairman and Managing Director, MultiSpectra Consultants, 23, Biplabi Ambika Chakraborty Sarani, Kolkata – 700029, West Bengal, INDIA. E-mail: [email protected] Businesses that restrict themselves to proprietary software like Microsoft Offce get a raw deal. Not only do they have to pay for the software but they have to factor in the cost incurred every time the software becomes corrupt. This includes the fee to be paid to the computer technician to re-install the software. All this creates a vicious cycle, where costs and delays keep mounting. It should be the primary aim of every business to develop a system that automates maintenance to the maximum possible extent. This is where open source software like LibreOffce, Apache OpenOffce, Scribus, GIMP, Inkscape, Firefox, Thunderbird,WordPress, VLC media player, etc, come in. My company, MultiSpectra Consultants, uses open source software to the maximum possible extent, thereby streamlining business processes. It makes updating the software and its maintenance very easy. The required software can be freely downloaded from the Internet and updates can also be applied by simply downloading the latest version of the relevant software. With free and open source software (FOSS) anyone is freely licensed to use, copy, study and change the software in any way, and the source code is openly shared so that people are encouraged to voluntarily improve the design of the software.