SPRING 2014 SPRING QUARTERLY MAGAZINE ALLIANCE REEF CORAL P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COASTAL CAPITAL Ecosystem Valuation for Decision Making in the Caribbean

COASTAL CAPITAL Ecosystem Valuation for Decision Making in the Caribbean RICHARD WAITE, LAURETTA BURKE, AND ERIN GRAY Photo: Katina Rogers Coastal Capital – Studies 2005-11 Coastal Capital – Studies 2005-11 Lower $, but important for food/jobs High $ High $ Photos: Crispin Zeenam (fisherman), Steve Linfield (wave break), K. Tkachenko (diving) Coastal Capital – Impacts? Main research questions • Which valuation studies have informed decision making in the Caribbean? • What made those studies successful in informing decision making? Use of coastal ecosystem valuation in decision making in the Caribbean • Low observed use so far • But, 20+ case studies offer lots of lessons Valuation supports MPA establishment St. Maarten, Haiti, Cuba, Bahamas, USA Photo: Tadzio Bervoets Valuation supports establishment of entry fees Bonaire, Dominican Republic, Mexico, Belize, St. Eustatius Image: STINAPA Valuation supports damage claims Belize, Jamaica, St. Eustatius, St. Maarten Source: U.S. Coast Guard. Valuation informs marine spatial planning Belize Source: Clarke et al. (2013). How else have valuation results been used? • Justify other policy changes (e.g., fishing regulations, offshore oil drilling ban) • Justify investment in management/conservation/ enforcement • Design Payments for Ecosystem Services schemes • Raise awareness/highlight economic importance Photo: Lauretta Burke Valuation results have informed decision making across the Caribbean Note: Not exhaustive. Why were these 20+ studies influential? …enabling conditions for use in decision -

Looe Key Mooring Buoy Service Interrupted July 15-18

Looe Key Mooring Buoy Service Interrupted July 15-18 Help Us Preserve the Reef The survey requires the same preferred The United States Geological Survey conditions for divers: good visibility and calm (USGS) will be conducting a mission to seas (typical of summer weather) in order to capture high-resolution baseline imagery of establish a high-resolution set of baseline Looe Key reef prior to multi-million dollar images that will allow evaluation of growth of coral restoration efforts taking place under restored corals over time. the Mission: Iconic Reefs initiative. This mission requires the removal of 20 mooring The FKNMS mooring system buoys so the towed, five-camera system (SQUID-5) can safely navigate slow passes Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary USGS prepares the SQUID-5 for capturing across the entire site, similar to mowing established a mooring buoy program 40 imagery at Eastern Dry Rocks. grass on a football field. The moorings will years ago. Looe Key Sanctuary Preservation be removed on, July 14th and returned to Area features 39 of the nearly 500 first-come, service on July 19th. first-served mooring buoys throughout FKNMS. 14 mooring buoys will remain This activity is a critical part of the $100 available during the survey work. Vessels are million Mission: Iconic Reefs restoration allowed to anchor elsewhere within the program, a partnership between federal, Sanctuary Preservation Area when mooring state and conservation and nonprofit buoys are unavailable--but only on sand. organizations and our local community in one of the largest commitments to coral We are requesting that the public refrain restoration anywhere in the world. -

Petition to List Eight Species of Pomacentrid Reef Fish, Including the Orange Clownfish and Seven Damselfish, As Threatened Or Endangered Under the U.S

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF COMMERCE PETITION TO LIST EIGHT SPECIES OF POMACENTRID REEF FISH, INCLUDING THE ORANGE CLOWNFISH AND SEVEN DAMSELFISH, AS THREATENED OR ENDANGERED UNDER THE U.S. ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Orange Clownfish (Amphiprion percula) photo by flickr user Jan Messersmith CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY SUBMITTED SEPTEMBER 13, 2012 Notice of Petition Rebecca M. Blank Acting Secretary of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Ave, NW Washington, D.C. 20230 Email: [email protected] Samuel Rauch Acting Assistant Administrator for Fisheries NOAA Fisheries National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration 1315 East-West Highway Silver Springs, MD 20910 E-mail: [email protected] PETITIONER Center for Biological Diversity 351 California Street, Suite 600 San Francisco, CA 94104 Tel: (415) 436-9682 _____________________ Date: September 13, 2012 Shaye Wolf, Ph.D. Miyoko Sakashita Center for Biological Diversity Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 553(e), and 50 C.F.R.§ 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity hereby petitions the Secretary of Commerce and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (“NOAA”), through the National Marine Fisheries Service (“NMFS” or “NOAA Fisheries”), to list eight pomacentrid reef fish and to designate critical habitat to ensure their survival. The Center for Biological Diversity (“Center”) is a non-profit, public interest environmental organization dedicated to the protection of imperiled species and their habitats through science, policy, and environmental law. The Center has more than 350,000 members and online activists throughout the United States. -

The Ecology and Economy of Coral Reefs: Considerations in Marketing Sustainability

The Ecology and Economy of Coral Reefs: Considerations in Marketing Sustainability Rick MacPherson Director, Conservation Programs Coral Reef Alliance Coral Reefs in Peril: Worldwide Status •2004: 70% of coral reefs “are under imminent risk of collapse through human pressures,” or “are under a longer term threat of collapse.” (Up from 58% in 2002.) RED = high risk YELLOW = medium risk BLUE = low risk Almost two-thirds of Caribbean reefs are threatened 3 RED = high risk YELLOW = medium risk BLUE = low risk Science says: • Climate Change and CO2: bleaching and acidification • Local threats undermine reef resilience to climate change • MMAs lack resources and community support • 50% of reefs could be destroyed by 2050 Coral Reefs in Peril: Regional Status •Caribbean reefs have suffered an 80% decline in cover during the past three decades. •80 to 90% of elkhorn and staghorn coral is gone. •Currently, coastal development threatens 33% of the reefs, land- based sources of pollution 35%, and over-fishing more than 60%. 5 Why Should You Care? CoralCoral reefsreefs provideprovide vitalvital ““ecosystemecosystem servicesservices”” 6 The Importance of Coral Reefs: Biodiversity • Only a very tiny portion of the sea bottom is covered by coral reefs (0.09%) with a total area about the size of Arizona or the UK • Yet, they’re home or nursery ground for 25% of all known marine species and (probably over one million species). 7 Biodiversity 8 The Importance of Coral Reefs: Medicine • 50% of current cancer medication research focuses on marine organisms found on coral reefs. 9 Importance of Coral Reefs: Food •Coral reefs worldwide yield a total value of over US$100 billion per year from food alone •Primary source of protein for over 1 billion people Constanza et al. -

Community Structure and Biogeography of Shore Fishes in the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea

Helgol Mar Res (2002) 55:252–284 DOI 10.1007/s10152-001-0090-y ORIGINAL ARTICLE Maroof A. Khalaf · Marc Kochzius Community structure and biogeography of shore fishes in the Gulf of Aqaba, Red Sea Received: 2 April 2001 / Received in revised form: 2 November 2001 / Accepted: 2 November 2001 / Published online: 24 January 2002 © Springer-Verlag and AWI 2002 Abstract Shore fish community structure off the Jorda- Introduction nian Red Sea coast was determined on fringing coral reefs and in a seagrass-dominated bay at 6 m and 12 m Coral reefs are one of the most complex marine ecosys- depths. A total of 198 fish species belonging to 121 gen- tems in which fish communities reach their highest de- era and 43 families was recorded. Labridae and Poma- gree of diversity (Harmelin-Vivien 1989). Morphological centridae dominated the ichthyofauna in terms of species properties and the geographical region of the coral reef richness and Pomacentridae were most abundant. Nei- determine the structure of the fish assemblages (Sale ther diversity nor species richness was correlated to 1980; Thresher 1991; Williams 1991). The ichthyofauna depth. The abundance of fishes was higher at the deep of coral reefs can be linked to varying degrees with adja- reef slope, due to schooling planktivorous fishes. At cent habitats (Parrish 1989) such as seagrass meadows 12 m depth abundance of fishes at the seagrass-dominat- (Ogden 1980; Quinn and Ogden 1984; Roblee and ed site was higher than on the coral reefs. Multivariate Ziemann 1984; Kochzius 1999), algal beds (Rossier and analysis demonstrated a strong influence on the fish as- Kulbicki 2000) and mangroves (Birkeland 1985; Thollot semblages by depth and benthic habitat. -

"Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean Biogeography"

A review of contemporary patterns of endemism for shallow water reef fauna in the Red Sea Item Type Article Authors DiBattista, Joseph; Roberts, May B.; Bouwmeester, Jessica; Bowen, Brian W.; Coker, Darren James; Lozano-Cortés, Diego; Howard Choat, J.; Gaither, Michelle R.; Hobbs, Jean-Paul A.; Khalil, Maha T.; Kochzius, Marc; Myers, Robert F.; Paulay, Gustav; Robitzch Sierra, Vanessa S. N.; Saenz Agudelo, Pablo; Salas, Eva; Sinclair-Taylor, Tane; Toonen, Robert J.; Westneat, Mark W.; Williams, Suzanne T.; Berumen, Michael L. Citation A review of contemporary patterns of endemism for shallow water reef fauna in the Red Sea 2015:n/a Journal of Biogeography Eprint version Post-print DOI 10.1111/jbi.12649 Publisher Wiley Journal Journal of Biogeography Rights This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: DiBattista, J. D., Roberts, M. B., Bouwmeester, J., Bowen, B. W., Coker, D. J., Lozano-Cortés, D. F., Howard Choat, J., Gaither, M. R., Hobbs, J.-P. A., Khalil, M. T., Kochzius, M., Myers, R. F., Paulay, G., Robitzch, V. S. N., Saenz-Agudelo, P., Salas, E., Sinclair-Taylor, T. H., Toonen, R. J., Westneat, M. W., Williams, S. T. and Berumen, M. L. (2015), A review of contemporary patterns of endemism for shallow water reef fauna in the Red Sea. Journal of Biogeography., which has been published in final form at http:// doi.wiley.com/10.1111/jbi.12649. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance With Wiley Terms and Conditions for self-archiving. Download date 23/09/2021 15:38:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10754/583300 1 Special Paper 2 For the virtual issue, "Red Sea and Western Indian Ocean Biogeography" 3 LRH: J. -

The Coral Reef Alliance • 2010 Annual Report INDIVIDUALLY, WE ARE ONE DROP

THE CORAL reef alliance • 2010 ANNUAL REPORT INDIVIDUALLY, WE ARE ONE DROP. TOGETHER, WE ARE AN OCEAN. -Ryunosuke Satoro, Poet 3 From the Executive Director From the Board Chair Forging new partnerships to save coral As a businessman and entrepreneur, I reefs is part of our DNA here at the Coral became involved with CORAL because Reef Alliance (CORAL). And looking back on I was impressed by their unique—and 2010, it’s through that quintessentially CORAL proven—strategy of improving reef health by approach that we addressed challenges and developing and implementing sustainable change. World headlines last year captured community-based solutions. As board chair, news of mass coral bleaching in Southeast Asia, Micronesia, I have realized an even deeper appreciation for the organization and the Caribbean, underscoring the urgency of our work. as I have worked more closely with CORAL’s talented team and Instead of getting mired in the gloomy news, CORAL expanded witnessed their unwavering commitment to our mission. our effective reef conservation strategies by cultivating key partnerships, including an exciting new collaboration with the Over the last year, the board of directors has been working Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. diligently to move the organization forward. While we said farewell to some long-time members, we also welcomed a We know that we have a narrow window of time to affect positive stellar new addition—Dr. Nancy Knowlton, Sant Chair for change for coral reefs. With that in mind, we are embarking on Marine Science at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of new projects that will dramatically extend our impact. -

Information Exchange for Marine Educators

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Information Exchange for Marine Educators Archive of Educational Programs, Activities, and Websites Environmental and Ocean Literacy Environmental literacy is key to preserving the nation's natural resources for current and future use and enjoyment. An environmentally literate public results in increased stewardship of the natural environment. Many organizations are working to increase the understanding of students, teachers, and the general public about the environment in general, and the oceans and coasts in particular. The following are just some of the large-scale and regional initiatives which seek to provide standards and guidance for our educational efforts and form partnerships to reach broader audiences. (In the interest of brevity, please forgive the abbreviations, the abbreviated lists of collaborators, and the lack of mention of funding institutions). The lists are far from inclusive. Please send additional entries for inclusion in future newsletters. Background Documents Environmental Literacy in America - What 10 Years of NEETF/Roper Research and Related Studies Say About Environmental Literacy in the U.S. http://www.neetf.org/pubs/index.htm The U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy devoted a full chapter on promoting lifelong ocean education, Ocean Stewardship: The Importance of Education and Public Awareness. It reviews the current status of ocean education and provides recommendations for strengthening national educational capacity. http://www.oceancommission.gov/documents/full_color_rpt/08_chapter8.pdf Environmental and Ocean Literacy and Standards Mainstreaming Environmental Education – The North American Association for Environmental Education is involved with efforts to make high-quality environmental education part of all education in the United States and has initiated the National Project for Excellence in Environmental Education. -

Guide to the Identification of Precious and Semi-Precious Corals in Commercial Trade

'l'llA FFIC YvALE ,.._,..---...- guide to the identification of precious and semi-precious corals in commercial trade Ernest W.T. Cooper, Susan J. Torntore, Angela S.M. Leung, Tanya Shadbolt and Carolyn Dawe September 2011 © 2011 World Wildlife Fund and TRAFFIC. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-9693730-3-2 Reproduction and distribution for resale by any means photographic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems of any parts of this book, illustrations or texts is prohibited without prior written consent from World Wildlife Fund (WWF). Reproduction for CITES enforcement or educational and other non-commercial purposes by CITES Authorities and the CITES Secretariat is authorized without prior written permission, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Any reproduction, in full or in part, of this publication must credit WWF and TRAFFIC North America. The views of the authors expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the TRAFFIC network, WWF, or the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The designation of geographical entities in this publication and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WWF, TRAFFIC, or IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The TRAFFIC symbol copyright and Registered Trademark ownership are held by WWF. TRAFFIC is a joint program of WWF and IUCN. Suggested citation: Cooper, E.W.T., Torntore, S.J., Leung, A.S.M, Shadbolt, T. and Dawe, C. -

Trait Decoupling Promotes Evolutionary Diversification of The

Trait decoupling promotes evolutionary diversification of the trophic and acoustic system of damselfishes rspb.royalsocietypublishing.org Bruno Fre´de´rich1, Damien Olivier1, Glenn Litsios2,3, Michael E. Alfaro4 and Eric Parmentier1 1Laboratoire de Morphologie Fonctionnelle et Evolutive, Applied and Fundamental Fish Research Center, Universite´ de Lie`ge, 4000 Lie`ge, Belgium 2Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Lausanne, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland Research 3Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics, Ge´nopode, Quartier Sorge, 1015 Lausanne, Switzerland 4Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90095, USA Cite this article: Fre´de´rich B, Olivier D, Litsios G, Alfaro ME, Parmentier E. 2014 Trait decou- Trait decoupling, wherein evolutionary release of constraints permits special- pling promotes evolutionary diversification of ization of formerly integrated structures, represents a major conceptual the trophic and acoustic system of damsel- framework for interpreting patterns of organismal diversity. However, few fishes. Proc. R. Soc. B 281: 20141047. empirical tests of this hypothesis exist. A central prediction, that the tempo of morphological evolution and ecological diversification should increase http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.1047 following decoupling events, remains inadequately tested. In damselfishes (Pomacentridae), a ceratomandibular ligament links the hyoid bar and lower jaws, coupling two main morphofunctional units directly involved in both feeding and sound production. Here, we test the decoupling hypothesis Received: 2 May 2014 by examining the evolutionary consequences of the loss of the ceratomandib- Accepted: 9 June 2014 ular ligament in multiple damselfish lineages. As predicted, we find that rates of morphological evolution of trophic structures increased following the loss of the ligament. -

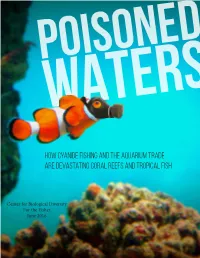

Poisoned Waters

POISONED WATERS How Cyanide Fishing and the Aquarium Trade Are Devastating Coral Reefs and Tropical Fish Center for Biological Diversity For the Fishes June 2016 Royal blue tang fish / H. Krisp Executive Summary mollusks, and other invertebrates are killed in the vicinity of the cyanide that’s squirted on the reefs to he release of Disney/Pixar’s Finding Dory stun fish so they can be captured for the pet trade. An is likely to fuel a rapid increase in sales of estimated square meter of corals dies for each fish Ttropical reef fish, including royal blue tangs, captured using cyanide.” the stars of this widely promoted new film. It is also Reef poisoning and destruction are expected to likely to drive a destructive increase in the illegal use become more severe and widespread following of cyanide to catch aquarium fish. Finding Dory. Previous movies such as Finding Nemo The problem is already widespread: A new Center and 101 Dalmatians triggered a demonstrable increase for Biological Diversity analysis finds that, on in consumer purchases of animals featured in those average, 6 million tropical marine fish imported films (orange clownfish and Dalmatians respectively). into the United States each year have been exposed In this report we detail the status of cyanide fishing to cyanide poisoning in places like the Philippines for the saltwater aquarium industry and its existing and Indonesia. An additional 14 million fish likely impacts on fish, coral and other reef inhabitants. We died after being poisoned in order to bring those also provide a series of recommendations, including 6 million fish to market, and even the survivors reiterating a call to the National Marine Fisheries are likely to die early because of their exposure to Service, U.S. -

Elkhorn Coral: Science of Recovery

Elkhorn Coral: Science of Recovery Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Once Abundant Coral Listed as Threatened Species Elkhorn coral, Acropora palmata, was once the most abundant stony coral on shallow reef crests and fore-reefs of the Caribbean and Florida reef tract. In the Florida Keys, this fast-growing coral with its thick antler-like branches formed extensive habitat for fish and marine invertebrates. By the early 1990s, elkhorn coral had experienced widespread losses throughout its range. A similar trend was seen in a close relative, staghorn coral, Acropora cervicornis. Multiple factors are thought to have contributed to coral declines, including impacts from hurricanes, coral disease, mass coral bleaching, climate change, coastal pollution, overfishing, and damage from boaters and divers. In 2006, the two species were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act. The recovery strategy, developed by NOAA Fisheries, included designating critical habitats in Florida, Puerto Rico Coral-eating snails covered in algae feed on elkhorn coral tissue. Photo: NOAA Fisheries and the U.S. Virgin Islands and called for further investigations into the factors that prevent natural recovery of the species. NOAA Scientists Investigate Causes of Coral Declines In 2004, scientists from NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center (Miami) began a long- In response to population term monitoring program in Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary to determine the current declines, the Center for population status of elkhorn coral and to better understand the primary threats and stressors Biological Diversity affecting its recovery. Understanding basic population statistics (coral recruitment and petitioned NOAA mortality) and the nature of stressors is critical to the species recovery plan and management Fisheries to list elkhorn of elkhorn coral within the sanctuary.