Baumer and Zimablist Sabermetric Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 District 41 Inter-League Rules

2021 District 41 Inter-League Rules Objective: Promote, develop, supervise, and voluntarily assist in all lawful ways, the interest of those who will participate in Little League Baseball. District 41 leagues participating in Inter- league play will adhere to the same rules for the 2021 Season. General: The “2021 Official Regulations and Playing Rules of Little League Baseball” will be strictly enforced, except those rules adopted by these Bylaws. All Managers, Coaches and Umpires shall familiarize themselves with all rules contained in the 2021 Official Regulations and Playing Rules of Little League Baseball (Blue Book/ LL app). All Managers, Coaches and Umpires shall familiarize themselves with District 41 2021 Inter-league Bylaws District 41 Division Bylaws • Tee-Ball Division: • Teams can either use the tee or coach pitch • Each field must have a tee at their field • A Tee-ball game is 60-minutes maximum. • Each team will bat the entire roster each inning. Official scores or standings shall not be maintained. • Each batter will advance one base on a ball hit to an infielder or outfielder, with a maximum of two bases on a ball hit past an outfielder. The last batter of each inning will clear the bases and run as if a home run and teams will switch sides. • No stealing of bases or advancing on overthrows. • A coach from the team on offense will place/replace the balls on the batting tee. • On defense, all players shall be on the field. There shall be five/six (If using a catcher) infield positions. The remaining players shall be positioned in the outfield. -

Brian Mccrea Brmccrea@Ufl

IDH 2930 Section 1D18 HNR Read Moneyball Tuesday 3 (9:35-10:25 a. m.) Little Hall 0117 Brian McCrea brmccrea@ufl. edu (352) 478-9687 Moneyball includes twelve chapters, an epilogue, and a (for me) important postscript. We will read and discuss one chapter a week, then finish with a week devoted to the epilogue and to the postscript. At our first meeting we will introduce ourselves to each other and figure out who amongst us are baseball fans, who not. (One need not have an interest in baseball to enjoy Lewis or to enjoy Moneyball; indeed, the course benefits greatly from disinterested business and math majors.) I will ask you to write informally every class session about the reading. I will not grade your responses, but I will keep a word count. At the end of the semester, we will have an Awards Ceremony for our most prolific writers. While this is not a prerequisite, I hope that everyone has looked at Moneyball the movie (starring Brad Pitt as Billy Beane) before we begin to work with the book. Moneyball first was published—to great acclaim—in 2003. So the book is fifteen-year’s old, and the “new” method of evaluating baseball players pioneered by Billy Beane has been widely adopted. Beane’s Oakland A’s no longer are as successful as they were in the early 2000s. What Lewis refers to as “sabremetrics”—the statistical analysis of baseball performance—has expanded greatly. Baseball now has statistics totally different from those in place as Lewis wrote: WAR (Wins against replacement), WHIP (Walks and hits per inning pitched) among them. -

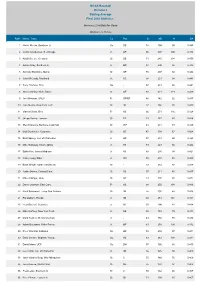

NCAA Baseball Division I Batting Average Final 2002 Statistics

NCAA Baseball Division I Batting Average Final 2002 Statistics Minimum 2.5 At-Bats Per Game Minimum 75 At-Bats Rank Name, Team CL Pos G AB H BA 1 Rickie Weeks, Southern U. So. SS 54 198 98 0.495 2 Curtis Granderson, Ill.-Chicago Jr. OF 55 207 100 0.483 3 Khalil Greene, Clemson Sr. SS 71 285 134 0.470 4 Antoin Gray, Southern U. Jr. OF 54 205 92 0.449 5 Anthony Bocchino, Marist Sr. OF 55 207 92 0.444 6 John McCurdy, Maryland Jr. SS 54 221 98 0.443 7 Terry Trofholz, TCU So. - 57 213 94 0.441 8 Steve Stanley, Notre Dame Sr. OF 68 271 119 0.439 9 Joe Wickman, UNLV Fr. SP/RP 46 142 62 0.437 10 Tom Merkle, New York Tech Sr. 3B 52 186 80 0.430 11 Vincent Sinisi, Rice Fr. 1B 66 271 116 0.428 12 Gregg Davies, Towson Sr. 1B 51 187 80 0.428 13 Wes Timmons, Bethune-Cookman Sr. INF 61 214 91 0.425 14 Matt Buckmiller, Columbia Sr. OF 47 158 67 0.424 15 Brett Spivey, Col. of Charleston Jr. OF 57 213 90 0.423 16 Mike Galloway, Miami (Ohio) Jr. 1B 59 223 94 0.422 17 Eddie Kim, James Madison Jr. 1B 60 235 99 0.421 18 Casey Long, Rider Jr. INF 55 210 88 0.419 19 Brian Wright, North Carolina St. Sr. - 59 232 97 0.418 20 Justin Owens, Coastal Caro. Sr. 1B 57 211 88 0.417 21 Mike Arbinger, Ohio Sr. -

NCAA Statistics Policies

Statistics POLICIES AND GUIDELINES CONTENTS Introduction ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 NCAA Statistics Compilation Guidelines �����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������3 First Year of Statistics by Sport ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 School Code ��������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������4 Countable Opponents ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 5 Definition ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Non-Countable Opponents ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Sport Implementation ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������5 Rosters ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������ 6 Head Coach Determination ���������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������6 Co-Head Coaches ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������7 -

Past CB Pitching Coaches of Year

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 62, No. 1 Friday, Jan. 4, 2019 $4.00 Mike Martin Has Seen It All As A Coach Bus driver dies of heart attack Yastrzemski in the ninth for the game winner. Florida State ultimately went 51-12 during the as team bus was traveling on a 1980 season as the Seminoles won 18 of their next 7-lane highway next to ocean in 19 games after those two losses at Miami. San Francisco, plus other tales. Martin led Florida State to 50 or more wins 12 consecutive years to start his head coaching career. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Entering the 2019 season, he has a 1,987-713-4 Editor/Collegiate Baseball overall record. Martin has the best winning percentage among ALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Mike Martin, the active head baseball coaches, sporting a .736 mark winningest head coach in college baseball to go along with 16 trips to the College World Series history, will cap a remarkable 40-year and 39 consecutive regional appearances. T Of the 3,981 baseball games played in FSU coaching career in 2019 at Florida St. University. He only needs 13 more victories to be the first history, Martin has been involved in 3,088 of those college coach in any sport to collect 2,000 wins. in some capacity as a player or coach. What many people don’t realize is that he started He has been on the field or in the dugout for 2,271 his head coaching career with two straight losses at of the Seminoles’ 2,887 all-time victories. -

Defensive Rebounding

53 Basketball Rebounding Drills and Games BreakthroughBasketball.com By Jeff and Joe Haefner Copyright Notice All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical. Any unauthorized use, sharing, reproduction, or distribution is strictly prohibited. © Copyright 2009 Breakthrough Basketball, LLC Limits / Disclaimer of Warranty The authors and publishers of this book and the accompanying materials have used their best efforts in preparing this book. The authors and publishers make no representation or warranties with respect to the accuracy, applicability, fitness, or completeness of the contents of this book. They disclaim any warranties (expressed or implied), merchantability, or fitness for any particular purpose. The authors and publishers shall in no event be held liable for any loss or other damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. This manual contains material protected under International and Federal Copyright Laws and Treaties. Any unauthorized reprint or use of this material is prohibited. Page | 3 Skill Codes for Each Drill Here’s an explanation of the codes associated with each drill. Most of the drills build a variety of rebounding skills, so we used codes to signify the skills that each drill will develop. Use the table of contents below and this key to find the drills that fit your needs. • Y = Youth • AG = Aggression • TH = Timing and Getting Hands Up • BX = Boxing out • SC = Securing / Chinning -

India's Take on Sports Analytics

PSYCHOLOGY AND EDUCATION (2020) 57(9): 5817-5827 ISSN: 00333077 India’s Take on Sports Analytics Rohan Mehta1, Dr.Shilpa Parkhi2 Student, Symbiosis Institute of Operations Mangement, Nashik, India Deputy Director, Symbiosis Institute of Operations Mangement, Nashik, India Email Id: [email protected] ABSTRACT Purpose – The aim of this paper is to study what is sports analytics, what are the different roles in this field, which sports are prominently using this, how big data has impacted this field, how this field is shaping up in Indian context. Also, the aim is to study the growth of job opportunities in this field, how B-schools are shaping up in this aspect and what are the interests and expectations of the B-school grads from this sector. Keywords Sports analytics, Sabermetrics, Moneyball, Technologies, Team sports, IOT, Cloud Article Received: 10 August 2020, Revised: 25 October 2020, Accepted: 18 November 2020 Design Approach analysis, he had done on approximately 10000 deliveries. Another writer, for one of the US The paper starts by explaining about the origin of magazines, F.C Lane was of the opinion that the sports analytics, the most naïve form of it, then batting average of the individual doesn’t reflect moves towards explaining the evolution of it over the complete picture of the individual’s the years (from emergence of sabermetrics to the performance. There were other significant efforts most advanced applications), how it has spread made by other statisticians or writers such as across different sports and how the applications of George Lindsey, Allan Roth, Earnshaw Cook till it has increased with the advent of different 1969. -

Why Did Cleveland Indians Sign Mike Napoli Instead of Pedro Alvarez?

Why did Cleveland Indians sign Mike Napoli instead of Pedro Alvarez? Hey, Hoynsie Paul Hoynes, cleveland.com CLEVELAND, Ohio – Do you have a question that you'd like to have answered in Hey, Hoynsie? Submit it here or Tweet him at @hoynsie. Hey, Hoynsie: Why did the Indians sign Mike Napoli, 34, for one year to play first base when Pedro Alvarez, 27, was available? Did management know Alvarez hit 27 home runs last season? -- Jimmy Garst, Roanoke, Va. Hey, Jimmy: The Indians did show interest in Alvarez, who was non-tendered by the Pirates and became a free agent. I think a couple of things probably came into play: No. 1, Alvarez was more expensive than the $7 million deal the Indians agreed to with Napoli. No. 2, the Indians felt Napoli helped them two ways – he gave their offense needed pop from the right side of the plate and he improved their defense. Napoli – whose deal should soon be made official – allows the Indians to move Carlos Santana to DH while he will get most of the time at first base. There is no doubt about Alvarez's power, but he made 23 errors at first base last season. I think the Indians preferred Napoli, considering the cost, at first and Santana at DH instead of Santana at first and Alvarez at DH. Hey, Hoynsie: The Reds seem interested in moving outfielder Jay Bruce. Is the Tribe done with its outfield or would it be interested in a guy who is as streaky hitter as there is, but definitely has pop? – Carl Neifer, Cincinnati. -

April 22, 1995

July 26, 2015 NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME things he used to like to do was take some rope, INDUCTION CEREMONY tie it around my waist and then tie it to the backstop while throwing me batting practice to try and keep me from lunging. It worked, but I came JANE FORBES CLARK: Craig, as home every day with rope burns around my waist. chairman of the National Baseball Hall of Fame, it My mother, never missed a game. Like is my honor to welcome you into the Hall of Fame most homes, she's the rock. We spent a lot of time family. together traveling around from field to field. I know CRAIG BIGGIO: Thank you. This is pretty she's happy today. I miss you so much, mom, and cool, I must say. What an incredible honor it is to I really wish you were here today. be standing in front of these great men. I played My brother Terry, my sister Gwen, we've against a lot of them, I admired a lot of them, but I been through a lot together. I love you guys. respected all of them. My in-laws, Joe and Yolanda Egan were Thank you, Jane, for this honor and all that tremendous help along with their three kids, Joey, you do for the Hall. I'd also like to thank Jeff Timmy, and Kevin. I took their daughter to Texas Idelson, Brad Horn, Whitney, and the Hall of Fame 25 years ago and we had three kids there. I was staff for keeping the integrity of the Hall of Fame. -

Seattle Mariners Opening Day Record Book

SEATTLE MARINERS OPENING DAY RECORD BOOK 1977-2012 All-Time Openers Year Date Day Opponent Att. Time Score D/N 1977 4/6 Wed. CAL 57,762 2:40 L, 0-1 N 1978 4/5 Wed. MIN 45,235 2:15 W, 3-2 N 1979 4/4 Wed. CAL 37,748 2:23 W, 5-4 N 1980 4/9 Wed. TOR 22,588 2:34 W, 8-6 N 1981 4/9 Thurs. CAL 33,317 2:14 L, 2-6 N 1982 4/6 Tue. at MIN 52,279 2:32 W, 11-7 N 1983 4/5 Tue. NYY 37,015 2:53 W, 5-4 N 1984 4/4 Wed. TOR 43,200 2:50 W, 3-2 (10) N 1985 4/9 Tue. OAK 37,161 2:56 W, 6-3 N 1986 4/8 Tue. CAL 42,121 3:22 W, 8-4 (10) N 1987 4/7 Tue. at CAL 37,097 2:42 L, 1-7 D 1988 4/4 Mon. at OAK 45,333 2:24 L, 1-4 N 1989 4/3 Mon. at OAK 46,163 2:19 L, 2-3 N 1990 4/9 Mon. at CAL 38,406 2:56 W, 7-4 N 1991 4/9 Tue. CAL 53,671 2:40 L, 2-3 N 1992 4/6 Mon. TEX 55,918 3:52 L, 10-12 N 1993 4/6 Tue. TOR 56,120 2:41 W, 8-1 N 1994 4/4 Mon. at CLE 41,459 3:29 L, 3-4 (11) D 1995 4/27 Thurs. -

The Numbers Game: Baseball's Lifelong Fascination with Statistics (Book Review)

The Numbers Game: Baseball's Lifelong Fascination with Statistics (Book Review) The American Statistician May 1, 2005 | Cochran, James J. The Numbers Game: Baseball's Lifelong Fascination with Statistics. Alan SCHWARZ. New York: Thomas Dunne Books, 2004, xv + 270 pp. $24.95 (H), ISBN: 0‐312‐322222‐4. I am amazed at how frequently I walk into a colleague's office for the first time and spot a copy of The Baseball Encyclopedia or Total Baseball on a bookshelf. How many statisticians developed and nurtured their interest in probability and statistics by playing Strat‐O‐ Matic[R] and/or APBA[R] baseball board games; reading publications like the annual The Bill James Baseball Abstract; or scanning countless box scores and current summary statistics in the Sporting News or in the sports section of the local newspaper, looking for an edge in a rotisserie baseball league? For many of us, baseball is what initially opened our eyes to the power of probability and statistics, and the sport continues to be an integral part of our lives (for evidence of this, attend the sessions or business meeting of the ASA's Statistics in Sports section at the next Joint Statistical Meetings). This is why so many probabilists and statisticians will enjoy reading Alan Schwarz's The Numbers Game: Baseball's Lifelong Fascination with Statistics. In this book, Schwarz effectively chronicles the ongoing association between baseball and statistics by describing the evolution of the sport from the mid‐nineteenth century through the beginning of the twenty‐first century, and looking at several of its most influential characters. -

General Media Guide

2019 LITTLE LEAGUE ® INTERNATIONAL GENERAL MEDIA GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 | About Little League/Communications Staff 4 | Board of Directors/International Advisory Board 5-6 | Administrative Levels 7 | Understanding the Local League 8-9 | Local League/General Media Policies 10-14 | Appearance of Little Leaguers in Non-Editorial Work 15-18 | Associated Terms of Little League 19 | Little League Fast Facts 20-25 | Detailed Timeline of Little League 26 | Divisions of Play 27 | Additional Little League Programs 28 | Age Determination Chart 29 | The International Tournament 30 | 2019 Little League World Series Information 31 | 2018 Little League World Series Champions 32 | Little League University 33 | Additional Educational Resources 34-38 | Little League Awards 39 | Little League Baseball Camp 40-42 | Little League Hall of Excellence 43-45 | AIG Accident and Liability Insurance For Little League 46-47 | Little League International Complex 48-49 | Little League International Congress 50 | Notable People Who Played Little League 51 | Official Little League Sponsors LITTLE LEAGUE® BASEBALL AND SOFTBALL 2 2019 GENERAL MEDIA GUIDE LITTLE LEAGUE® BASEBALL AND SOFTBALL ABOUT LITTLE LEAGUE® Founded in 1939, Little League® Baseball and Softball is the world’s largest organized youth sports program, with more than two million players and one million adult volunteers in every U.S. state and more than 80 other countries. During its nearly 80 years of existence, Little League has seen more than 40 million honored graduates, including public officials, professional athletes, award-winning artists, and a variety of other influential members of society. Each year, millions of people follow the hard work, dedication, and sportsmanship that Little Leaguers® display at our seven baseball and softball World Series events, the premier tournaments in youth sports.