The Politics of Defection and Power Game in Nigeria: Insights from the 7 Th Lower Legislative Chamber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria Sgo.Sagepub.Com

SGOXXX10.1177/2158244015576053SAGE OpenSuleiman and Karim 576053research-article2015 Article SAGE Open January-March 2015: 1 –11 Cycle of Bad Governance and Corruption: © The Author(s) 2015 DOI: 10.1177/2158244015576053 The Rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria sgo.sagepub.com Mohammed Nuruddeen Suleiman1 and Mohammed Aminul Karim1 Abstract This article argues that bad governance and corruption particularly in the Northern part of Nigeria have been responsible for the persistent rise in the activities of Jama’atu Ahlis Sunna Lidda’awati wal-Jihad (JASLWJ), Arabic for “people committed to the propagation of the tradition and jihad.” It is also known as “Boko Haram,” commonly translated as “Western education is sin.” Based on qualitative data obtained through interviews with Nigerians, this article explicates how poor governance in the country has created a vicious cycle of corruption, poverty, and unemployment, leading to violence. Although JASLWJ avows a religious purpose in its activities, it takes full advantage of the social and economic deprivation to recruit new members. For any viable short- or long-term solution, this article concludes that the country must go all-out with its anti- corruption crusade. This will enable the revival of other critical sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing, likely ensuring more employment. Should the country fail to stamp out corruption, it will continue to witness an upsurge in the activities of JASLWJ, and perhaps even the emergence of other violent groups. The spillover effects may be felt not only across Nigeria but also within the entire West African region. Keywords Nigeria, governance, corruption, militancy, Boko Haram, democracy Introduction own desired objectives and methods. -

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa?

Towards a New Type of Regime in Sub-Saharan Africa? DEMOCRATIC TRANSITIONS BUT NO DEMOCRACY Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos cahiers & conférences travaux & recherches les études The Institut français des relations internationales (Ifri) is a research center and a forum for debate on major international political and economic issues. Headed by Thierry de Montbrial since its founding in 1979, Ifri is a non-governmental and a non- profit organization. As an independent think tank, Ifri sets its own research agenda, publishing its findings regularly for a global audience. Using an interdisciplinary approach, Ifri brings together political and economic decision-makers, researchers and internationally renowned experts to animate its debate and research activities. With offices in Paris and Brussels, Ifri stands out as one of the rare French think tanks to have positioned itself at the very heart of European debate. The opinions expressed in this text are the responsibility of the author alone. The Sub-Saharian Africa Program is supported by: Translated by: Henry Kenrick, in collaboration with the author © Droits exclusivement réservés – Ifri – Paris, 2010 ISBN: 978-2-86592-709-8 Ifri Ifri-Bruxelles 27 rue de la Procession Rue Marie-Thérèse, 21 75740 Paris Cedex 15 – France 1000 Bruxelles – Belgique Tél. : +33 (0)1 40 61 60 00 Tél. : +32 (0)2 238 51 10 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Internet Website : Ifri.org Summary Sub-Saharan African hopes of democratization raised by the end of the Cold War and the decline in the number of single party states are giving way to disillusionment. -

Democracy and Disorder Impeachment of Governors and Political Development in Nigeria’S Fourth Republic

Taiwan Journal of Democracy, Volume 11, No. 2: 163-183 Democracy and Disorder Impeachment of Governors and Political Development in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic Oarhe Osumah Abstract This essay, based on data derived from existing literature and reports, examines the impeachment of state governors in Nigeria since the return to civil rule in May 1999. It shows that six state governors have been impeached. This number far exceeds the cases in Nigeria’s previous three democratic experiments combined, the First Republic (1963-1966), the Second Republic (1979-1983), and the botched Third Republic (1991-1993). Although, at face value, the impeachment cases since May 1999 tend to portray the fulfilment of the liberal democratic tradition, in fact, they demonstrate political disorder, or garrison democracy. Keywords: Impeachment, legislature, democracy, disorder, godfathers. The question of impeachment has been much overlooked since the Nixon and Clinton eras in the United States. In many instances, full and fair democratic elections are the best way to end an unpopular or corrupt government. In Nigeria, since the return to democratic rule in May 1999 after long years of military authoritarianism, impeachment has been a recurrent feature, one ostensibly designed to check abuse of political power. Threats of impeachment and a number of impeachment proceedings have been raised or initiated since the inauguration of the Fourth Republic. The number during the Fourth Republic far exceeds the impeachments, or threats of it, during Nigeria’s previous three democratic experiments combined; the First Republic (1963-1966), the Second Republic (1979-1983), and the botched Third Republic (1991-1993). Indeed, impeachment has been more regularly deployed during the current period of Nigeria’s constitutional history than in the historical experiences of the most advanced democracies, such as the United States and Britain. -

First Election Security Threat Assessment

SECURITY THREAT ASSESSMENT: TOWARDS 2015 ELECTIONS January – June 2013 edition With Support from the MacArthur Foundation Table of Contents I. Executive Summary II. Security Threat Assessment for North Central III. Security Threat Assessment for North East IV. Security Threat Assessment for North West V. Security Threat Assessment for South East VI. Security Threat Assessment for South South VII. Security Threat Assessment for South West Executive Summary Political Context The merger between the Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), All Nigerian Peoples Party (ANPP) and other smaller parties, has provided an opportunity for opposition parties to align and challenge the dominance of the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). This however will also provide the backdrop for a keenly contested election in 2015. The zoning arrangement for the presidency is also a key issue that will define the face of the 2015 elections and possible security consequences. Across the six geopolitical zones, other factors will define the elections. These include the persisting state of insecurity from the insurgency and activities of militants and vigilante groups, the high stakes of election as a result of the availability of derivation revenues, the ethnic heterogeneity that makes elite consensus more difficult to attain, as well as the difficult environmental terrain that makes policing of elections a herculean task. Preparations for the Elections The political temperature across the country is heating up in preparation for the 2015 elections. While some state governors are up for re-election, most others are serving out their second terms. The implication is that most of the states are open for grab by either of the major parties and will therefore make the electoral contest fiercer in 2015 both within the political parties and in the general election. -

Nigeria Risk Assessment 2014 INSCT MIDDLE EAST and NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE

INSCT MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE INSTITUTE FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AND COUNTERTERRORISM Nigeria Risk Assessment 2014 INSCT MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA INITIATIVE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report—which uses open-source materials such as congressional reports, academic articles, news media accounts, and NGO papers—focuses on three important issues affecting Nigeria’s present and near- term stability: ! Security—key endogenous and exogenous challenges, including Boko Haram and electricity and food shortages. ! The Energy Sector—specifically who owns Nigeria’s mineral resources and how these resources are exploited. ! Defense—an overview of Nigeria’s impressive military capabilities, FIGURE 1: Administrative Map of Nigeria (Nations Online Project). rooted in its colonial past. As Africa’s most populous country, Nigeria is central to the continent’s development, which is why the current security and risk situation is of mounting concern. Nigeria faces many challenges in the 21st century as it tries to accommodate its rising, and very young, population. Its principal security concerns in 2014 and the immediate future are two-fold—threats from Islamist groups, specifically Boko Haram, and from criminal organizations that engage in oil smuggling in the Niger Delta (costing the Nigerian exchequer vast sums of potential oil revenue) and in drug smuggling and human trafficking in the North.1 The presence of these actors has an impact across Nigeria, with the bloody, violent, and frenzied terror campaign of Boko Haram, which is claiming thousands of lives annually, causing a refugee and internal displacement crises. Nigerians increasingly have to seek refuge to avoid Boko Haram and military campaigns against these insurgents. -

Immediate Release 26 November 2018 What Nigeria

Immediate Release 26 November 2018 What Nigeria needs to worry about, by Obasanjo As Sultan of Sokoto called for more funding to research and extension … Nigeria’s changing demography driven by rapid growth in population coupled with a stagnant and in some cases retrogressing agricultural productivity are challenges that the country needs to worry about, says Nigeria’s former President, Chief Olusegun Obasanjo at the just concluded Nigeria Zero Hunger Forum (NZHF) in Sokoto. The former president noted that by 2050, the country’s population would be over 400 million, and the increase in population would put pressure on food systems as more people would require food to eat for survival. Chief Obasanjo said Nigeria should begin to think and proffer solutions to this coming challenge that the country would be faced with in no distant future. Chief Obasanjo’s position was reechoed by the former Governor of Adamawa State, Alh. Murtala Nyako who canvassed for greater youth involvement in agriculture. Alh. Nyako underscored the importance of nutrition to the peace and security of the nation, stressing that a well-nourished population is calmer than one that is not. Alh. Nyako added that the restiveness being experienced across the nation is correlated to poor nutrition among children who end up stunted with low intelligence quotient. His Eminence, Sultan of Sokoto Mahammadu Sa’ad Abubakar, commended the Nigeria Zero Hunger initiative, and lauded Chief Obasanjo for taking the driver seat to move the initiative forward. The Sultan, who is the spiritual head of Muslims in Nigeria, called on the Federal and State governments to fund agricultural research and extensions services. -

The Judiciary and Nigeria's 2011 Elections

THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS CSJ CENTRE FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE (CSJ) (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS Written by Eze Onyekpere Esq With Research Assistance from Kingsley Nnajiaka THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiii First Published in December 2012 By Centre for Social Justice Ltd by Guarantee (Mainstreaming Social Justice In Public Life) No 17, Flat 2, Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, P.O. Box 11418 Garki, Abuja Tel - 08127235995; 08055070909 Website: www.csj-ng.org ; Blog: http://csj-blog.org Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-978-931-860-5 Centre for Social Justice THE JUDICIARY AND NIGERIA’S 2011 ELECTIONS PAGE iiiiiiiii Table Of Contents List Of Acronyms vi Acknowledgement viii Forewords ix Chapter One: Introduction 1 1.0. Monitoring Election Petition Adjudication 1 1.1. Monitoring And Project Activities 2 1.2. The Report 3 Chapter Two: Legal And Political Background To The 2011 Elections 5 2.0. Background 5 2.1. Amendment Of The Constitution 7 2.2. A New Electoral Act 10 2.3. Registration Of Voters 15 a. Inadequate Capacity Building For The National Youth Service Corps Ad-Hoc Staff 16 b. Slowness Of The Direct Data Capture Machines 16 c. Theft Of Direct Digital Capture (DDC) Machines 16 d. Inadequate Electric Power Supply 16 e. The Use Of Former Polling Booths For The Voter Registration Exercise 16 f. Inadequate DDC Machine In Registration Centres 17 g. Double Registration 17 2.4. Political Party Primaries And Selection Of Candidates 17 a. Presidential Primaries 18 b. -

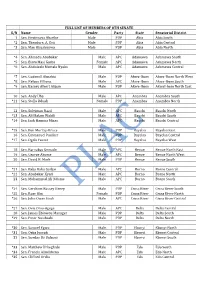

Full List of Members of the 8Th Senate

FULL LIST OF MEMBERS OF 8TH SENATE S/N Name Gender Party State Senatorial District 1 Sen. Enyinnaya Abaribe Male PDP Abia Abia South *2 Sen. Theodore. A. Orji Male PDP Abia Abia Central *3 Sen. Mao Ohuabunwa Male PDP Abia Abia North *4 Sen. Ahmadu Abubakar Male APC Adamawa Adamawa South *5 Sen. Binta Masi Garba Female APC Adamawa Adamawa North *6 Sen. Abdulaziz Murtala Nyako Male APC Adamawa Adamawa Central *7 Sen. Godswill Akpabio Male PDP Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom North West *8 Sen. Nelson Effiong Male APC Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom South *9 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Male PDP Akwa-Ibom AkwaI-bom North East 10 Sen. Andy Uba Male APC Anambra Anambra South *11 Sen. Stella Oduah Female PDP Anambra Anambra North 12 Sen. Suleiman Nazif Male APC Bauchi Bauchi North *13 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Male APC Bauchi Bauchi South *14 Sen. Isah Hamma Misau Male APC Bauchi Bauchi Central *15 Sen. Ben Murray-Bruce Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa East 16 Sen. Emmanuel Paulker Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa Central *17 Sen. Ogola Foster Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa West 18 Sen. Barnabas Gemade Male APC Benue Benue North East 19 Sen. George Akume Male APC Benue Benue North West 20 Sen. David B. Mark Male PDP Benue Benue South *21 Sen. Baba Kaka Garbai Male APC Borno Borno Central *22 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Male APC Borno Borno North 23 Sen. Mohammed Ali Ndume Male APC Borno Borno South *24 Sen. Gershom Bassey Henry Male PDP Cross River Cross River South *25 Sen. Rose Oko Female PDP Cross River Cross River North *26 Sen. -

Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017)

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 3, March, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2019 HRMARS Nigerian Conundrum: Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017) Emmanuel Chimezie Eyisi To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i3/5673 DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v9-i3/5673 Received: 21 Feb 2019, Revised: 08 March 2019, Accepted: 18 March 2019 Published Online: 21 March 2019 In-Text Citation: (Eyisi, 2019) To Cite this Article: Eyisi, E. C. (2019). Nigerian Conundrum: Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017). International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 9(3), 251– 267. Copyright: © 2019 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 9, No. 3, 2019, Pg. 251 - 267 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 251 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 9 , No. 3, March, 2019, E-ISSN: 2222 -6990 © 2019 HRMARS Nigerian Conundrum: Democracy and the Hegemony of Corruption in Nigeria (1999-2017) Emmanuel Chimezie Eyisi (Ph.D) Department of Sociology/Psychology/Criminology, Faculty of Management and Social Sciences Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu-alike Ikwo, Ebonyi State. -

(Im) Partial Umpire in the Conduct of the 2007 Elections

VOLUME 6 NO 2 79 THE INDEPENDENT NATIONAL ELECTORAL COMMISSION AS AN (IM) PARTIAL UMPIRE IN THE CONDUCT OF THE 2007 ELECTIONS Uno Ijim-Agbor Uno Ijim-Agbor is in the Department of Political Science at the University of Calabar Pmb 1115, Calabar, Nigeria Tel: +080 355 23537 e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT As a central agency in the democratic game, the role of an electoral body such as the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) is clearly of paramount importance in the process of transition to and consolidation of democracy. Unfortunately in Nigeria the performance of this institutional umpire since the First Republic has instead been a source of crisis and a threat to the existence of the Nigerian state. The widely perceived catastrophic failure of INEC in the April 2007 general elections was only one manifestation for the ‘performance crisis’ of antecedent electoral umpires in the Nigerian First, Second and Third republics. The paper highlights the malignant operational environment as a major explanation for the manifest multiple disorders of the elections and concludes that INEC’s conduct was tantamount to partiality. Thus, while fundamental changes need to be considered in the enabling law setting up INEC, ensuring the organisation’s independence, and guaranteeing its impartiality, the paper suggests that membership of the commission should be confined to representatives nominated by their parties and a serving judge appointed by the judiciary as chairman of the commission. INTRODUCTION In political theory the authority of the government in democracies derives solely from the consent of the governed. The mechanism through which that consent is translated into governmental authority is the regular conduct of elections. -

The Executive Powers of the President (2) Updated

THE EXECUTIVE POWERS OF THE PRESIDENT INTRODUCTION Following the declaration of National Emergency in Nigeria to deal with corruption’s perilous counter attack against the Nigerian State. President Buhari on the 5th of July 2018 signed the Executive Order No. 6 on the preservation of Assets Connected with Serious Corruption and other Related Offences.The Executive Order comprises a preamble, seven sections, two schedules and some essential features. The first feature begins with acknowledging corruption, the second talks on protecting the asset from dissipation, the third talks about the specification of persons and court cases and person to whom it applies. Names cover former IGP, Orji uzorkalu, ex adamawa state gov-murtala nyako, Gabriel suswam, sani yerima (ex- Zamfara gov), sule lamido etc What this means is, if government suspects a person has illegally acquired assets, such person is charged to court and government will subsequently take over the assets temporarily pending when the judicial process will run its course. In the President’s own words “…I have decided to issue the Executive Order No. 6 of 2018 to inter alia restrict dealings in suspicious assets subject to investigation or inquiry bordering on corruption in order to preserve such assets from dissipation and to deprive alleged criminals of the proceeds of their illicit activities which can otherwise be employed to allure, pervert and/or intimidate the investigation and judicial processes or for acts of terrorism, financing of terrorism, kidnapping, sponsorship of ethnic and religious violence, economic sabotage and cases of economic and financial crimes, including acts contributing to the economic adversity of the Federal Republic Of Nigeria and against the overall interest of justice and the welfare of the Nigerian State” It is obvious that the above-mentioned Order is out to fight against corruption, a project which is very crucial to the viability and continuous well-being of Nigeria. -

Download This PDF File

THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES ISSN 2321 - 9203 www.theijhss.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES An Appraisal of Social and Political Relationship between Hausa and Igbo in Nigeria Ishaku Abubakar Lecturer, Department of Hausa Umar Suleiman College of Education Gashua, Yobe State Garba Mohammed Lecturer, Department of Hausa, Omar Suleiman College of Education Gashua, Yobe State Abstract: Relationship can be defined as a state of affairs existing between those having relation or dealings. Hausa and Igbo are two different language speakers and from different region but certain factors bring them together. The paper pointed out these factors that correlate the two language speakers such as business, country, politics, religion, system of government etc. The paper also employed interview and unobtrusive observation as a means of data collection. Twenty- five (25) respondents were selected which includes Hausa and Igbo whose ages are above 50 years old as the target population Keywords: Language, region, politics, speakers, relationship 1. Introduction Relationship has been defined as the way in which two more people or group regard and behave toward each other. Relationship starts when one shares a border, house, shop, ward, business, farm, birth, marriage orcountry. Historically, Igbo language is among languages of the southeastern Nigeria, the language has dialects and one among the languages having high population in African continent. They have traditional occupations, farming and business. They farm yam and cassava etc., also have annual yam festival. Before the coming of the colonial masters, Igbo people were left behind politically. They have many different cultures, most of them are Christian, some Muslims, and some practice tradition religion.