LIVELIHOODS and FOOD SECURITY TRUST FUND – DELTA 1 EVALUATION Evaluation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Usg Humanitarian Assistance to Burma

USG HUMANITARIAN ASSISTANCE TO BURMA RANGOON CITY AREA AFFECTED AREAS Affected Townships (as reported by the Government of Burma) American Red Cross aI SOURCE: MIMU ASEAN B Implementing NGO aD BAGO DIVISION IOM B Kyangin OCHA B (WEST) UNHCR I UNICEF DG JF Myanaung WFP E Seikgyikanaunglo WHO D UNICEF a WFP Ingapu DOD E RAKHINE b AYEYARWADY Dala STATE DIVISION UNICEF a Henzada WC AC INFORMA Lemyethna IC TI Hinthada PH O A N Rangoon R U G N O I T E G AYEYARWADY DIVISION ACF a U Zalun S A Taikkyi A D ID F MENTOR CARE a /DCHA/O D SC a Bago Yegyi Kyonpyaw Danubyu Hlegu Pathein Thabaung Maubin Twantay SC RANGOON a CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE AC Hmawbi See Inset WC AC Htantabin Kyaunggon DIVISION Myaungmya Kyaiklat Nyaungdon Kayan Pathein Einme Rangoon SC/US JCa CWS/IDE AC Mayangone ! Pathein WC AC Î (Yangon) Thongwa Thanlyin Mawlamyinegyun Maubin Kyauktan Kangyidaunt Twantay CWS/IDE AC Myaungmya Wakema CWS/IDE Kyauktan AC PACT CIJ Myaungmya Kawhmu SC a Ngapudaw Kyaiklat Mawlamyinegyun Kungyangon UNDP/PACT C Kungyangon Mawlamyinegyun UNICEF Bogale Pyapon CARE a a Kawhmu Dedaye CWS/IDE AC Set San Pyapon Ngapudaw Labutta CWS/IDE AC UNICEF a CARE a IRC JEDa UNICEF a WC Set San AC SC a Ngapudaw Labutta Bogale KEY SC/US JCa USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP DOD Pyinkhayine Island Bogale A Agriculture and Food Security SC JC a Air Transport ACTED AC b Coordination and Information Management Labutta ACF a Pyapon B Economy and Market Systems CARE C !Thimphu ACTED a CARE Î AC a Emergency Food Assistance ADRA CWS/IDE AC CWS/IDE aIJ AC Emergency Relief Supplies Dhaka IOM a Î! CWS/IDE AC a UNICEF a D Health BURMA MERLIN PACT CJI DJ E Logistics PACT ICJ SC a Dedaye Vientiane F Nutrition Î! UNDP/PACT Rangoon SC C ! a Î ACTED AC G Protection UNDP/PACT C UNICEF a Bangkok CARE a IShelter and Settlements Î! UNICEF a WC AC J Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene WC WV GCJI AC 12/19/08 The boundaries and names used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the U.S. -

Social Assessment for Ayeyarwady Region and Shan State

AND DEVELOPMENT May 2019 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized SOCIAL ASSESSMENT FOR AYEYARWADY REGION AND SHAN STATE Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition 1 Myanmar: Maternal and Child Cash Transfers for Improved Nutrition Ministry of Social Welfare, Relief and Resettlement May 2019 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................... 5 List of Abbreviations .......................................................................................................................... 9 List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... 10 List of BOXES ................................................................................................................................... 10 A. Introduction and Background....................................................................................................... 11 1 Objectives of the Social Assessment ................................................................................................11 2 Project Description ..........................................................................................................................11 3 Relevant Country and Sector Context..............................................................................................12 3.1 -

Labutta Interagency Warehouse

The Logistics Cluster is lead by MYANMAR LOGISTICS CLUSTER Labutta Interagency Warehouse The Logistics Cluster in Myanmar is offering 5 types of services to UN agencies, INGOs and International organizations: 1. Air Cargo facilitation 2. Temporary storages facilities 3. Common transport Service 4. Logistics Hub s 5. Logistics Information management This snapshot refers to the Labutta inter-agency warehouses facility that is one out of the 5 set up by the Logistics Cluster in the Delta region. (Erecting storage units and wireless system in the Labutta hub) Works to extend the concrete floor available finished an additional three storage unit have been built for the storing of NFIs. (Logistics hub in Labutta) The Labutta hub is currently operational with 7 storage units (1,840 smq). Out of these operational mobile units, one is dedicated to UNICEF (240sqm), two to WFP (560 sqm) and one available for interagency NFI storage (1,040 sqm). A wireless connection system has also been installed in the hub. (Assembling of office unit in the Labutta hub) Cargo and items are delivered to the Hubs through the Common Transport Service set up by the Logistics Cluster from Yangon to the different hubs located in the Delta region: Pyapon, Bogale, Maw’Gyun, Labutta and Pathein. For information related to this service please refer to the Common Transport Service Snapshot available on the cluster web page. For additional information please refer to the (Logistics Cluster Hub in Labutta) Logistics Cluster Web page: UN agencies and NGOs such as UNICEF, WFP and http://www.logcluster.org/mm08a Merlin are currently stocking their items into the inter agency hub set up by the Logistics cluster in Labutta. -

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development a Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative

Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 1 2 Metta Development Foundation Table of Contents Forward, Executive Director 2 A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative - Executive Summary 6 01. Introduction – Waves of Change The Ayeyarwady Delta 10 Metta’s Presence in the Delta. The Tsunami 11 02. Cyclone Nargis –The Disaster 12 03. The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 14 04. The Global Proposal 16 The Proposal 16 Connecting Partners - Metta as Hub 17 05. Rehabilitation, Reconstruction and Development August 2008-July 2011 18 Introduction 18 A01 – Relief, Recovery and Capacity Building: Rice and Roofs 18 A02 – Food Security: Sowing and Reaping 26 A03 – Education: For Better Tomorrows 34 A04 – Health: Surviving and Thriving 40 A05 – Disaster Preparedness and Mitigation: Providing and Protecting 44 A06 – Lifeline Systems and Transportation: The Road to Safety 46 Conclusion 06. Local Partners – The Communities in the Delta: Metta Meeting Needs 50 07. International Partners – The Donor Community Meeting Metta: Metta Day 51 08. Reporting and External Evaluation 52 09. Cyclones and Earthquakes – Metta put anew to the Test 55 10. Financial Review 56 11. Beyond Nargis, Beyond the Delta 59 12. Thanks 60 List of Abbreviations and Acronyms 61 Staff Directory 62 Volunteers 65 Annex 1 - The Emergency Response – Metta on Site 68 Annex 2 – Maps 76 Annex 3 – Tables 88 Rehabilitation, Reconstruction & Development A Post Cyclone Nargis Initiative 3 Forword Dear Friends, Colleagues and Partners On the night of 2 May 2008, Cyclone Nargis struck the delta of the Ayeyarwady River, Myanmar’s most densely populated region. The cyclone was at the height of its destructive potential and battered not only the southernmost townships but also the cities of Yangon and Bago before it finally diminished while approaching the mountainous border with Thailand. -

Township Environmental Assessment 2017

LABUTTA TOWNSHIP ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT 2017 MYANMAR ENVIRONMENT INSTITUTE This report has been prepared by Myanmar Environment Institute as part of BRACED Myanmar Consortium(2015-2017) Final Report Page I Abbreviation and Acronyms BRACED Building Resilience and Adaptation to Climate Extremes and Disasters CRA Community Risk Assessment CSO Civil Society Organization CSR Corporate Social Responsibility ECD Environmental Conservation Department EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan EU European Union IEE Initial Environmental Examination Inh/km2 Inhabitant per Kilometer Square KBA Key Biodiversity Area MEI Myanmar Environment Institute MIMU Myanmar Information Management Unit MOECAF Ministry of Environmental Conservation and Forestry MONREC Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation NCEA National Commission for Environmental Affair NGO Non-Governmental Organization RIMES Regional Integrated Multi -Hazard Early Warning System SEA Strategic Environmental Assessment TDMP Township Disaster Management Plan TEA Township Environmental Assessment TSP Township Final Report Page II Table of Content Executive Summary ______________________________________________ 1 Chaper 1 Introduction and Background ____________________________ 12 1. 1 Background __________________________________________________________________ 12 1. 2 Introduction of BRACED ________________________________________________________ 13 1. 3 TEA Goal and Objective ________________________________________________________ 15 1. 4 SEA -

K Y a I K L a T B O G a L E P Y a P O N Mawlamyinegyun Wakema Labutta

95°10’0"E 95°20’0"E 95°30’0"E MASOYEIN SABYUZU THAINGGON KANYINTABIN TALOKSU PAUK TAN THAHTEGON KYWEGYAUNG TUMYAUNG KYONPA THITCHEM-APYA KYAUNGSHAGWIN SAWKEGYDUNG ONBINZU SEINHAING THONGWA DIPALE THAYUTGYI KYONKYAIK KYAWZAN THITCHEINWA ONBINZU ALANDUT ONBINZU SIBWACHAUNG THAYETKON YAZUDAINGDUNTABE THAUNGDAN KYAIKPI DANONGYAUNG PAYA GY I BYANGYI BYANGYI DIPALE GAYAN-AWA NGAPIGYAUNG Wakema SINGYAUNG PAYA GY I HTITOLO-APYA MATUKWIN BAMAW LE-EINDAN PEGON KUNYINGYAUNG THONEINDAN KYONMANGE SHWEMEIKCHAUNG BOLU PANGUGYAUNG OKPON KYUNKAMA KYONLAMU YEZUN ALEGWIN MAYANGYAUNG KANZAUK-ATET MYAUNGTHA HLEZEIK KANAUNG SAWKEGYAUNG KANZUDAUK PAYA IK THITPYUGYAUNG KAYINZU ASUGYIPALUNZA GAYAN GWEBINZEIK KYUNPYATTHAT KYONLAMU KAYINZU TA L U WA KYIZU MAGWEDAN MYITBO SABEGON PYINMAGON YENIGYAUNG METALAING TAGUNDAING DALIN KYUNPA AUNGBANGYAUNG SABYUZU KYONZALU WEGYAUNG WEDAUNG HLEZEIK HLEZEIK KWMINGYAUNG PAYA GYAUNG KWINGYAUNG LAWKADAT TEGYAUNG LE-EINDAN KWINGYI AKAW PABEZU TAGUNDAING KYWEDALIN KYWEGYAUNG KUNTHIGYAUNG-APYA PATHE INZ U PAYACHAUNG KYONLATA KWINGYAUNG WANETCHAUNG KATHABAUNG WEDAUNG BAMAW AUNGDO THAYETCHAUNG KYONLAMU WETKWIN TAUNGBOGON NGA-EINDAN KUNTHIGYAUNGGYI KANAZOGYAUNG PYINMAGON MAYAN TA M AN G YI HPUTI Kyaiklat MEZ ALI YOKSAING KUNBINGYAUNG TALOKSEIK KALAGYIWA YWATHIT SANEIK TAUNGALE NPOPON MINHLAZU YEGYAW-WA KAYINZU KANYINGYAUNG SITCHAUNG KYONLATA AMAWCHOK HTEIKPAUK HTEINGAING KYAUKYEZU KYONKYAIK AUNGHLAING NAUKPANDO YAKAINGZU TONIEGYAUNG THAYAGON AINGBON TEIKPWIN NGE-EINZU SANEIK-AUKSU Mawlamyinegyun MAYET TA M O N KANGYI NYAUNGGYAUNG SHWEBOZU -

Administrative Map

Myanmar Information Management Unit Myanmar Administrative Map 94°E 96°E 98°E 100°E India China Bhutan Bangladesh Along India Vietnam KACHIN Myanmar Dong Laos South China Sea Bay of Bengal / Passighat China Thailand Daporija Masheng SAGAING 28°N Andaman Sea Philippines Tezu 28°N Cambodia Sea of the Philippine Gulf of Thailand Bangladesh Pannandin !( Gongshan CHIN NAWNGMUN Sulu Sea Namsai Township SHAN MANDALAY Brunei Malaysia Nawngmun MAGWAY Laos Tinsukia !( Dibrugarh NAY PYI TAW India Ocean RAKHINE Singapore Digboi Lamadi KAYAH o Taipi Duidam (! !( Machanbaw BAGO Margherita Puta-O !( Bomdi La !( PaPannssaauunngg North Lakhimpur KHAUNGLANHPU Weixi Bay of Bengal Township Itanagar PUTA-O MACHANBAW Indonesia Township Township Thailand YAN GON KAY IN r Khaunglanhpu e !( AYE YARWADY MON v Khonsa i Nanyun R Timor Sea (! Gulf of Sibsagar a Martaban k Fugong H i l NANYUN a Township Don Hee M !( Jorhat Mon Andaman Sea !(Shin Bway Yang r Tezpur e TANAI v i TANINTHARYI NNaaggaa Township R Sumprabum !( a Golaghat k SSeellff--AAddmmiinniisstteerreedd ZZoonnee SUMPRABUM Township i H Gulf of a m Thailand Myanmar administrative Structure N Bejiang Mangaldai TSAWLAW LAHE !( Tanai Township Union Territory (1) Nawgong(nagaon) Township (! Lahe State (7) Mokokchung Tuensang Lanping Region (7) KACHIN INDIA !(Tsawlaw Zunheboto Hkamti INJANGYANG Hojai Htan Par Kway (! Township !( 26°N o(! 26°N Dimapur !( Chipwi CHIPWI Liuku r Township e Injangyang iv !( R HKAMTI in w Township d HPAKANT MYITKYINA Lumding n i Township Township Kohima Mehuri Ch Pang War !(Hpakant -

Hazard Profile of Myanmar: an Introduction 1.1

Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................ I List of Figures ................................................................................................................ III List of Tables ................................................................................................................. IV Acronyms and Abbreviations ......................................................................................... V 1. Hazard Profile of Myanmar: An Introduction 1.1. Background ...................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Myanmar Overview ......................................................................................................... 2 1.3. Development of Hazard Profile of Myanmar : Process ................................................... 2 1.4. Objectives and scope ....................................................................................................... 3 1.5. Structure of ‘Hazard Profile of Myanmar’ Report ........................................................... 3 1.6. Limitations ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. Cyclones 2.1. Causes and Characteristics of Cyclones in the Bay of Bengal .......................................... 5 2.2. Frequency and Impact .................................................................................................... -

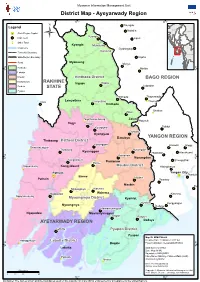

Ayeyarwady Region

Myanmar Information Management Unit District Map - Ayeyarwady Region 95° E 96° E Paungde Legend INDIA Nattalin CHINA .! State/Region Capital Kyangin Main Town Ü Zigon !( Other Town Kyangin Myanaung Coast Line !( Gyobingauk Kanaung Township Boundary THAILAND State/Region Boundary Okpho Road Myanaung Monyo N Kyeintali N ° Hinthada !( ° 8 Minhla 8 1 1 Labutta Maubin Hinthada District BAGO REGION Myaungmya RAKHINE Ingapu Ingapu Pathein STATE Letpadan Pyapon Hinthada Thayarwady Gwa Lemyethna Lemyethna !( Thonse Hinthada Okekan Zalun !( Ngathaingchaung Zalun !( Ahpyauk !( Yegyi Yegyi Kyonpyaw Taikkyi Danubyu Kyonpyaw Danubyu YANGON REGION Thabaung Pathein District Kyaunggon Hmawbi Hlegu Shwethaungyan !( Thabaung Nyaungdon Kyaunggon Htantabin Htaukkyant N N ° Pantanaw ° 7 7 1 Nyaungdon 1 Kangyidaunt Pantanaw Shwepyithar Einme Ngwesaung Kangyidaunt Maubin District !( Hlaingtharya Pathein Yangon City .! .! Thanlyin Einme Maubin Pathein Twantay Maubin Kyauktan Myaungmya Wakema Ngapudaw Wakema Kawhmu Ngayokekaung !( Myaungmya District Kyaiklat Kyaiklat Kungyangon Myaungmya Dedaye Mawlamyinegyun Ngapudaw Mawlamyinegyun Bogale Pyapon AYEYARWADY REGION Dedaye Labutta Pyapon District Pyapon Map ID: MIMU764v04 Hainggyikyun Creation Date: 23 October 2017.A4 N Labutta District N !( ° Bogale Projection/Datum: Geographic/WGS84 ° 6 6 1 1 Labutta Data Sources: MIMU Base Map: MIMU Boundaries: MIMU/WFP Pyinsalu Place Name: Ministry of Home Affairs (GAD) !( Ahmar translated by MIMU !( Email: [email protected] Website: www.themimu.info Kilometers Copyright © Myanmar Information Management Unit 2017. May be used free of charge with attribution. 0 10 20 40 95° E 96° E Disclaimer: The names shown and the boundaries used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.. -

Recent Evolution of the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) Delta and the Impacts of Anthropogenic Activities: a Review and Remote Sensing Survey

GEOMOR-107231; No of Pages 23 Geomorphology 365 (2020) 107231 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Geomorphology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/geomorph Recent evolution of the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) Delta and the impacts of anthropogenic activities: A review and remote sensing survey Dan Chen a, Xing Li a,⁎, Yoshiki Saito b,c, J. Paul Liu d, Yuanqiang Duan a, Shu'an Liu a, Lianpeng Zhang a a School of Geography, Geomatics and Planning, Jiangsu Normal University, Xuzhou 221116, China b Estuary Research Center (EsReC), Shimane University, 1060, Nishikawatsu-Cho, Matsue 690-8504, Japan c Geological Survey of Japan, AIST, Higashi 1-1-1, Tsukuba 305-8567, Japan d Department of Marine, Earth & Atmospheric Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695, USA article info abstract Article history: Intensive studies have been conducted globally in the past decades to understand the evolution of several large Received 21 November 2019 deltas. However, despite being one of the largest tropical deltas, the Irrawaddy (Ayeyarwady) Delta has received rel- Received in revised form 28 April 2020 atively little attention from the research community. To reduce this knowledge gap, this study aims to provide a Accepted 28 April 2020 comprehensive assessment of the delta's evolution and identify its influencing factors using remote sensing images Available online 20 May 2020 from 1974 to 2018, published literature and available datasets on the river, and human impacts in its drainage basin. Our results show that 1) Based on the topographic and geomorphological features, the funnel-shaped Irrawaddy Keywords: fl Delta evolution Delta can be divided into two parts: the upper uvial plain and the lower low-lying coastal plain; 2) The past 44- Shoreline change year shoreline changes show that overall accretion of the delta shoreline was at a rate of 10.4 m/year, and approx- Fluvial geomorphology imately 42% of the shoreline was subjected to erosion from 1974 to 2018. -

Land Settlement Reports Burma Akyab District. Amherst District

Land Settlement Reports Burma Akyab District. MF-3960 reel 140. Report on the settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1886-87 [microform]. Rangoon : Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Printing, 1888. V/27/314/223 OCLC # 24160149 MF-3960 reel 141. Report on the settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1887-88 [microform]. Rangoon : Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Printing, 1888. V/27/314/224 OCLC # 24161496 MF-3981 reel 31. Report on the revision settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1901-1902. [microform]. Rangoon : Printed at British Burma Press, 1903. V/27/314/225 OCLC # 24204343. MF-3981 reel 32. Report on the revision settlement operations in the Akyab District, season 1902-1903. [microform]. Rangoon : Printed at the British Burma Press, 1903. V/27/314/226 OCLC # 24204365 MF-3981 reel 33. Report on the summary settlement of three cadastrally surveyed circles in the Akyab District, season 1903-04 [microform] : accompanied by map and four appendices. Rangoon : Office of Superintendent Govt. Printing, 1905. V/27/314/227 OCLC # 24204378 MF-15057 r.1 Report on the revision settlement operations in the Akyab district, season 1913-17. / Smart, Robert Baddington. Rangoon : Office of the Superintendent, Government Printing, Burma, 1918. Contents : 1, General description of the settlement area.--2, The people.--3, Agricultural.--4, Occupancy.--5, The expiring settlement.--6, The new settlement.--7, Miscellaneous remarks and suggestions.--Appendices.--Maps.; Includes notes, resolution and V (9) 4128 = V/27/314/228 OCLC # 85774574 Amherst District. MF-3981 reel 34. Report on the settlement operations in the Amherst District, season 1891-92. -

Socioeconomic Characteristics of Hilsa Fishers in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar Opportunities and Challenges

A position Paper Prepared for the New Perspectives on Climate Resilient Drylands Development Project Socioeconomic characteristics of hilsa fishers in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar Opportunities and challenges Wae Win Khaing, Michael Akester, Eugenia Merayo Garcia, Annabelle Bladon and Essam Yassin Mohammed Country Report Fisheries; Poverty Keywords: December 2018 Sustainable fisheries; ocean; poverty reduction; livelihoods; communities About the authors Wae Win Khaing, Network Activities Group; Michael Akester, WorldFish Myanmar, Eugenia Merayo Garcia, International Institute for Environment and Development; Annabelle Bladon, International Institute for Environment and Development; Essam Yassin Mohammed, International Institute for Environment and Development. Corresponding author email [email protected] Produced by IIED’s Shaping Sustainable Markets group IIED's Shaping Sustainable Markets group works to make sure that local and global markets are fair and can help poor people and nature thrive. Our research focuses on the mechanisms, structures and policies that lead to sustainable and inclusive economies. Our strength is in finding locally appropriate solutions to complex global and national problems. Acknowledgements We would like to thank all participants of the socioeconomic survey that formed the basis of this report – particularly the Ayeyarwady Delta fisherfolk. We thank the Ayeyarwady Region Department of Fisheries, township Department of Fisheries offices, and the Myanmar Fisheries Federation for their support. We also recognise the contributions of WorldFish, the FISH CGIAR Research program, and Bobby Maung and Myo Zaw Aung from the Network Activities Group. Published by IIED, December 2018 Wae Win Khaing, Michael Akester, Eugenia Merayo Garcia, Annabelle Bladon and Essam Yassin Mohammed (editor) (2018) Socioeconomic characteristics of hilsa fishers in the Ayeyarwady Delta, Myanmar: Opportunities and challenges.