Somatic Movement and Embodiment Are Terms That Are Used to Describe the Phenomena of Movement As Experienced from Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

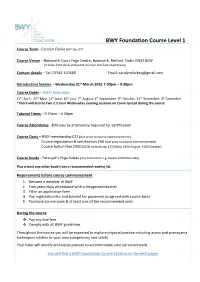

BWY Foundation Course Level 1

BWY Foundation Course Level 1 Course Tutor - Carolyn Clarke BWY Dip: DCT Course Venue – Babworth Court Yoga Centre, Babworth, Retford, Notts DN22 8EW (2 miles from A1 & accessible on main line East coast trains) Contact details – Tel: 07561 107660 Email: [email protected] Introductory Session – Wednesday 31st March 2021 7.00pm – 9.30pm Course Dates – 2021- Saturdays 17th April: 22nd May: 12th June: 10th July: 7th August: 4th September: 9th October: 13th November: 4th December *There will also be two 2.5 hour Wednesday evening sessions on Zoom spread during the course Tutorial Times – 9.45am – 4.30pm Course Attendance - 80% course attendance required for certification Course Costs – BWY membership £37 (due prior to course commencement) Course registration & certification £60 (due prior to course commencement) Course tuition fees £500 (£100 on booking: £150 May: £150 August: £100 October) Course books - Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (any translation e.g. Swami Satchidananda) Plus a least one other book from a recommended reading list Requirements before course commencement 1. Become a member of BWY 2. Two years class attendance with a recognised teacher 3. Fill in an application form 4. Pay registration fee and tutorial fee payments as agreed with course tutor 5. Purchase course book & at least one of the recommended ones During the course v Pay any due fees v Comply with all BWY guidelines Throughout the course you will be expected to explore physical practice including asana and pranayama techniques relative to your own competency and safety. Your tutor will modify and adjust posture to accommodate your personal needs. You will find a BWY Foundation Course Syllabus on the next pages BRITISH WHEEL OF YOGA SYLLABUS - FOUNDATION COURSE 1 The British Wheel of Yoga Foundation Course 1 focuses on basic practical techniques and personal development taught in the context of the philosophy that underpins Yoga. -

Asana Sarvangasana

Sarvângâsana (Shoulder Stand) Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 18, 2006 © 2004 by International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. Benagh, Barbara. Salamba sarvangasana (shoulderstand). Yoga Journal, Nov 2001, pp. 104-114. Cole, Roger. Keep the neck healthy in shoulderstand. My Yoga Mentor, May 2004, no. 6. Article available online: http://www.yogajournal.com/teacher/1091_1.cfm. Double shoulder stand: Two heads are better than one. Self, mar 1998, p. 110. Ezraty, Maty, with Melanie Lora. Block steady: Building to headstand. Yoga Journal, Jun 2005, pp. 63-70. “A strong upper body equals a stronger Headstand. Use a block and this creative sequence of poses to build strength and stability for your inversions.” (Also discusses shoulder stand.) Freeman, Richard. Threads of Universal Form in Back Bending and Finishing Poses workshop. 6th Annual Yoga Journal Convention, 27-30 Sep 2001, Estes Park, Colorado. “Small, subtle adjustments in form and attitude can make problematic and difficult poses produce their fruits. We will look a little deeper into back bends, shoulderstands, headstands, and related poses. Common difficulties, injuries, and misalignments and their solutions [will be] explored.” Grill, Heinz. The shoulderstand. Yoga & Health, Dec 1999, p. 35. ___________. The learning curve: Maintaining a proper cervical curve by strengthening weak muscles can ease many common pains in the neck. -

Rudolf Laban in the 21St Century: a Brazilian Perspective

DOCTORAL THESIS Rudolf Laban in the 21st Century: A Brazilian Perspective Scialom, Melina Award date: 2015 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 Rudolf Laban in the 21st Century: A Brazilian Perspective By Melina Scialom BA, MRes Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of Dance University of Roehampton 2015 Abstract This thesis is a practitioner’s perspective on the field of movement studies initiated by the European artist-researcher Rudolf Laban (1879-1958) and its particular context in Brazil. Not only does it examine the field of knowledge that Laban proposed alongside his collaborators, but it considers the voices of Laban practitioners in Brazil as evidence of the contemporary practices developed in the field. As a modernist artist and researcher Rudolf Laban initiated a heritage of movement studies focussed on investigating the artistic expression of human beings, which still reverberates in the work of artists and scholars around the world. -

Course Details the British Wheel of Yoga (BWY)

Course Details me to observe your posture work and see how you interact within a group. The British Wheel of Yoga (BWY) Diploma Course is designed to train I will also set you some written work to give you a real flavour of the committed yoga practitioners to be safe and effective teachers of yoga. course. At this stage you are still not committing yourself to the course The course is in four modules: and will need to seriously consider whether you intend to progress further. All students wishing to join the course must join BWY and pay the course Unit 1 Anatomy and physiology related to yoga practice, stress and relaxation, nutrition, deposit prior to the commencement of the first course day. basic breathing and the setting up of a yoga class. Selected practices. Course Set Books Unit 2 Prana, pranayama, mudras, bandhas, chakras, Hatha Yoga Pradipika and All students are required to own the set books: observation and analysis in teaching. Selected practices An Anatomy and Physiology text. Unit 3 Yoga philosophy, concentration, meditation, mantra, issues of health and safety in Yoga Sutras of Patanjali teaching and first aid. Selected practices. Hatha Yoga Pradipika Bhagavad Gita Unit 4 Professional studies and practical aspects of teaching yoga postures. Selected practices. The Major Upanishads Adult Learning, Adult Teaching Daines, Daines and Graham The course will consist of monthly meetings 9.30am – 4.30pm and two Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha Swami Satyananda weekend residentials over 3 years. Students are required to continue regular attendance at a weekly class with a BWY teacher; follow home There are a number of translations of the texts and information will be study and home practice schedules; to complete written work and to given at the Introductory Day about the books to be used during the prepare presentations and mini teaching sessions to be given during course. -

Aikido: a Martial Art with Mindfulness, Somatic, Relational, and Spiritual Benefits for Veterans

Spirituality in Clinical Practice © 2017 American Psychological Association 2017, Vol. 4, No. 2, 81–91 2326-4500/17/$12.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/scp0000134 Aikido: A Martial Art With Mindfulness, Somatic, Relational, and Spiritual Benefits for Veterans David Lukoff Richard Strozzi-Heckler Sofia University, Palo Alto, California Strozzi Institute, Oakland, California Aikido is a martial art that originated in Japan and incorporates meditation and breathing techniques from Zen Buddhism. Like all martial arts, it requires mindful concentration and physical exertion. In addition, it is a compassion practice that also provides a spiritual perspective and includes social touch. These components make Aikido a unique form of mindfulness that has the potential to be particularly appealing to veterans coming from a Warrior Ethos tradition who are used to rigorous somatic training. Mindfulness practices have shown efficacy with veterans, and the self- compassion, spiritual, and social touch dimensions of Aikido also offer benefits for this population, many of whom are struggling with these issues. Several pilot Aikido programs with veterans that show promise are described. Keywords: mindfulness, veterans, PTSD, spirituality, martial arts Aikido, like all martial arts, requires mindful spiritual dimensions in his martial art and de- concentration and physical exertion. In addi- scribed it as “The Way of Harmony.” tion, it is a compassion practice that provides a Aikido emphasizes working with a partner, spiritual perspective and social human touch. rather than sparring, grappling, or fighting Aikido emerged in twentieth-century Japan fol- against an opponent in competitive tourna- lowing an evolution of martial arts over hun- ments. Aikido techniques neutralize and control dreds of years from a system of fighting arts attackers instead of violently defeating them. -

Yoga and Psychology and Psychotherapy

Yoga and Psychology and Psychotherapy Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 27, 2006 © 2004 by International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. “How is the field of psychotherapy to become progressively more informed by the infinite wisdom of spirit? It will happen through individuals who allow their own lives to be transformed—their own inner source of knowing to be awakened and expressed.” —Yogi Amrit Desai NOTE: See also the “Counseling” bibliography. For eating disorders, please see the “Eating Disorders” bibliography, and for PTSD, please see the “PTSD” bibliography. Books and Dissertations Abegg, Emil. Indishche Psychologie. Zürich: Rascher, 1945. [In German.] Abhedananda, Swami. The Yoga Psychology. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1960, 1983. “This volume comprises lectures delivered by Swami Abhedananda before a[n] . audience in America on the subject of [the] Yoga-Sutras of Rishi Patanjali in a systematic and scientific manner. “The Yoga Psychology discloses the secret of bringing under control the disturbing modifications of mind, and thus helps one to concentrate and meditate upon the transcendental Atman, which is the fountainhead of knowledge, intelligence, and bliss. “These lectures constitute the contents of this memorial volume, with copious references and glossaries of Vyasa and Vachaspati Misra.” ___________. True Psychology. Calcutta: Ramakrishna Vedanta Math, 1982. “Modern Psychology does not [address] ‘a science of the soul.’ True Psychology, on the other hand, is that science which consists of the systematization and classification of truths relating to the soul or that self-conscious entity which thinks, feels and knows.” Agnello, Nicolò. -

Master Thesis Document Schwartz

Copyright by Ray Eliot Schwartz 2006 Exploring the Space Between: The Effect of Somatic Education on Agency and Ownership Within a Collaborative Dance-Making Process by Ray Eliot Schwartz, B.F.A., C.B.M.C.P. Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts University of Texas at Austin May 2006 Exploring the Space Between: The Effect of Somatic Education on Agency and Ownership Within a Collaborative Dance-Making Process Approved by Supervising Committee: _____________________________ Kent DeSpain _____________________________ Jill Dolan _____________________________ David Justin ______________________________ Kristen Neff Acknowledgements I would like to thank my many dance colleagues and teachers. In particular: the faculty and students of the North Carolina School of the Arts 1984-1987, the faculty and students of Virginia Commonwealth University’s Department of Dance and Choreography 1987-1992, the faculty and students of The University of Texas at Austin 2003-2006, Martha Myers, Nancy Stark Smith, Mike Vargas, Donna Faye Burchfield, Laura Faure, Phillip Grosser, Rob Petres, Sardono Kusumo, Ramli Ibrahim, Liz Lerman, Lucas Hoving, Steve Paxton, Chris Aiken, Andrew Harwood, K.J. Holmes, Kathleen Hermesdorff, Sandy and Denny Sorenson, Deborah Thorpe, Sarah Gamblin, the members of Steve’s House Dance Collective, the Zen Monkey Project, them, and Sheep Army/Elsewhere Dance Theater. Their collective wisdom, as it -

Somatics Studies and Dance GLENNA BATSON DSC, PT, MA with the IADMS DANCE EDUCATORS’ COMMITTEE, 2009

RESOURCE PAPER FOR DANCERS AND TEACHERS Somatics Studies and Dance GLENNA BATSON DSC, PT, MA WITH THE IADMS DANCE EDUCATORS’ COMMITTEE, 2009. INTRODUCTION 2 HISTORY 2 KEY CONCEPTS 3 NOVEL LEARNING CONTEXTS 4 SENSORY ATTUNEMENT 4 AUGMENTED REST 5 SOMATIC PRACTICES IN DANCE TECHNIQUE 6 IDEOKINESIS 6 THE FELDENKRAIS METHOD® 7 ALEXANDER TECHNIQUE 8 BODY-MIND CENTERING 9 FURTHER SUBSTANTIATION 10 STUDY AND CERTIFICATION 10 FURTHER THOUGHTS 10 ADDITIONAL RESOURCES 11 REFERENCES 11 1. INTRODUCTION “I think, therefore I move” Thomas Hanna Since the 1970s, a growing number of dancers have sought additional training in mind- body techniques loosely called “somatic studies,” or simply, “somatics.”1 Once considered esoteric and far removed from daily technique class, somatics is now a household word in a dancer’s training. University dance programs worldwide now offer substantive somatic studies2 and degree programs,3 and community studios offer extensive study and certification in various practices.4,5 2. HISTORY Somatic studies also have been referred to as body therapies, bodywork, body-mind integration, body-mind disciplines, movement awareness, and movement (re) education.6 The origins of western somatic education are rooted in a philosophical revolt against Cartesian dualism.7,8 In the European Gymnastik movement of the late 19th century, for example, somatic pioneers Francois Delsarte, Emile JaquesDalcroze, and Bess Mensendieck sought to replace the reigning ideology of rigor in physical training with a more “natural” approach based on listening -

The British Wheel of Yoga

The British Wheel of Yoga BWY Guidelines for Teaching Yoga in Pregnancy Purpose: The purpose of the document is to give safely guidelines to teachers who may have a pregnant woman in their general classes. Let your students know that if they become pregnant you need to be informed (in confidence, of course). Pregnant women are generally advised not to attend a general yoga class before 15 weeks gestation, when the pregnancy is considered to be established. Safe Yoga practice in the first trimester would comprise gentle breathing, relaxation and meditation. Direct women to a dedicated Pregnancy Yoga class where possible, especially if they are joining a yoga class for the first time. Ensure that a pregnant woman in your class has informed her health professional about her attendance at a Yoga class. Although Yoga will help with any anxiety, all medical conditions need to be dealt with by the medical profession. Every pregnancy is unique. We need to encourage pregnant students to learn to listen to their bodies. How they feel is often their best guide to what they can and cannot do. Students may need to modify a pose or rest at any time. Blood sugar levels can dip more frequently in pregnancy. Although one is advised not to eat before doing Yoga, pregnant women may need to have a light snack before class. Ligaments and tendons may soften during pregnancy due to hormonal changes. Those who are very flexible (often experienced yogis, gymnasts, dancers) should avoid overstretching and hyperextension of the joints. Students may need to bend their knees when moving in and out of asymmetric poses to protect the SI joints. -

Prime Somatics Think • Move • Feel • Live

SOMATIC SYSTEMS INSTITUTE S 1 Prime Somatics think • move • feel • live CLINICAL SOMATIC EDUCATION TM PROFESSIONAL TRAINING PROGRAM PROGRAM PROSPECTUS FULL CERTIFICATION PROGRAM CONTENTS CONTENTS Greetings from the Director . 3 About Prime Somatics . 4 Greetings from the Director . 3 ThomasAbout HannaPrime Somatics. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 4 . 5 ProfessionalThomas Hanna Praise .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 . 5 SSIProfessional History & MissionPraise . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 5 . 6 PraiseSSI Historyfor Prime & SomaticsMission .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 . 6 StudentPraise Testimonialsfor Prime Somatics . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 6 . 7 CurriculumStudent Testimonials . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 7. 9 StudentCurriculum Support . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 9. 9 Student Support . 9 Certification . 10 Certification . 10 Society Membership . 10 Society Membership . 10 SocietySociety Benefits Benefits . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10. 10 StudentStudent Benefits Benefits . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 10 . 10 FacultyFaculty & &Director Director . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 11. 11 Campus/HousingCampus/Housing . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 12. 12 CONTACT INFORMATION Somatic Systems Institute 32 Masonic Street Northampton, MA 01060-3038 (877) 586.2555 or (413) 586.2555 for more information, including schedules & tuition — or to apply to the training program — visit us today at somatics.org/training S 1 Prime Somatics think • move • feel • live Dear Prospective Student, On behalf of the entire faculty at the Somatic Systems -

Exploring the Integration of Somatic Concepts Into the Teaching and Learning of Ballet

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Sensing and Shaping from Within: Exploring the Integration of Somatic Concepts into the Teaching and Learning of Ballet THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS in Dance by Alana Rae Isiguen Thesis Committee: Professor Loretta Livingston, Chair Professor Mary Corey Professor Tong Wang 2015 © 2015 Alana Rae Isiguen TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS iii ABSTRACT OF THESIS iv CHAPTER ONE: From Balanchine to Bartenieff: My Path Incorporating Somatic Thought into Ballet Beginnings 1 Ballet Pedagogy: How We Teach and Learn, and Looking Forward 4 Optimal Setting for Somatic Introductions? 5 Thesis Research and Project 7 CHAPTER TWO: Somatic Foundations What are “somatics”? 10 The Alexander Technique 11 Laban Movement Analysis/Bartenieff Fundamentals 13 Ideokinesis 15 Insights from Injury 17 CHAPTER THREE: Looking at the Role of Somatics in Undergraduate Dance Curricula A Brief Overview of Dance in Higher Education in America 19 Somatic Offerings within BFA Conservatory Dance Programs 20 Making Connections from Somatics to Dance Technique 23 CHAPTER FOUR: Creating a Pedagogical Framework Breath and Kinesthesia 27 Connectivity 29 Intention and Initiation 31 Experiential Anatomy 32 CHAPTER FIVE: Research Project with Undergraduate Students 35 Teaching and Learning with Breath and Kinesthesia 36 Discovering Connectivity 37 Finding Intention and Initiation 40 Exploring Anatomy Through Movement 42 CHAPTER SIX: Conclusions Time 45 Empowerment 46 Community 47 Final Thoughts 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY 50 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my thesis committee chair, Professor Loretta Livingston. Every step of the way your insights into academic writing and wealth of knowledge have soundly guided me. -

DANCE SCIENCE and SOMATICS in TRAINING and PERFORMANCE by HANNAH KAY ANDERSEN a THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Danc

DANCE SCIENCE AND SOMATICS IN TRAINING AND PERFORMANCE by HANNAH KAY ANDERSEN A THESIS Presented to the School of Music and Dance and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts June 2017 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Hannah Kay Andersen Title: Dance Science and Somatics in Training and Performance This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Fine Arts degree in the School of Music and Dance by: Dr. Steven J. Chatfield Chairperson Sherrie Barr Member Sarah Ebert Member Shannon Mockli Member and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Hannah Kay Andersen iii THESIS ABSTRACT Hannah Kay Andersen Master of Fine Arts School of Music and Dance June 2017 Title: Dance Science and Somatics in Training and Performance This mixed methods investigation analyzes the effect of a novel somatics training program on dance skills. Fourteen dancers were divided into treatment and control groups. The treatment group participated in an eight-week workshop on the use of the spine utilizing sensory experiences, mini-lectures, and dance exercises. During entry and exit, all dancers learned two phrases by video containing the same motor-patterns with contrasting choreographic intents; Phrase A fluid, sustained and slow, Phrase B, dynamically enhanced. Participants performed each phrase for the camera, to be scored by a judging panel. Descriptive statistical analysis of judging data suggests the workshop positively affected their execution of skills in Phrase A, over B.