2019 Barn Owl Special Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Adaptations of Diurnal and Nocturnal Raptors

Seminars in Cell and Developmental Biology 106 (2020) 116–126 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/semcdb Review Visual adaptations of diurnal and nocturnal raptors T Simon Potiera, Mindaugas Mitkusb, Almut Kelbera,* a Lund Vision Group, Department of Biology, Lund University, Sölvegatan 34, S-22362 Lund, Sweden b Institute of Biosciences, Life Sciences Center, Vilnius University, Saulėtekio Av 7, LT-10257 Vilnius, Lithuania HIGHLIGHTS • Raptors have large eyes allowing for high absolute sensitivity in nocturnal and high acuity in diurnal species. • Diurnal hunters have a deep central and a shallow temporal fovea, scavengers only a central and owls only a temporal fovea. • The spatial resolution of some large raptor species is the highest known among animals, but differs highly among species. • Visual fields of raptors reflect foraging strategies and depend on the divergence of optical axes and on headstructures • More comparative studies on raptor retinae (preferably with non-invasive methods) and on visual pathways are desirable. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Raptors have always fascinated mankind, owls for their highly sensitive vision, and eagles for their high visual Pecten acuity. We summarize what is presently known about the eyes as well as the visual abilities of these birds, and Fovea point out knowledge gaps. We discuss visual fields, eye movements, accommodation, ocular media transmit- Resolution tance, spectral sensitivity, retinal anatomy and what is known about visual pathways. The specific adaptations of Sensitivity owls to dim-light vision include large corneal diameters compared to axial (and focal) length, a rod-dominated Visual field retina and low spatial and temporal resolution of vision. -

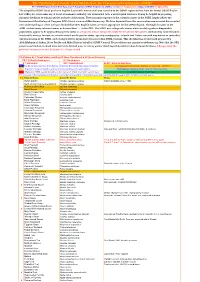

2017 Namibia, Botswana & Victoria Falls Species List

Eagle-Eye Tours Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls November 2017 Bird List Status: NT = Near-threatened, VU = Vulnerable, EN = Endangered, CR = Critically Endangered Common Name Scientific Name Trip STRUTHIONIFORMES Ostriches Struthionidae Common Ostrich Struthio camelus 1 ANSERIFORMES Ducks, Geese and Swans Anatidae White-faced Whistling Duck Dendrocygna viduata 1 Spur-winged Goose Plectropterus gambensis 1 Knob-billed Duck Sarkidiornis melanotos 1 Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca 1 African Pygmy Goose Nettapus auritus 1 Hottentot Teal Spatula hottentota 1 Cape Teal Anas capensis 1 Red-billed Teal Anas erythrorhyncha 1 GALLIFORMES Guineafowl Numididae Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris 1 Pheasants and allies Phasianidae Crested Francolin Dendroperdix sephaena 1 Hartlaub's Spurfowl Pternistis hartlaubi H Red-billed Spurfowl Pternistis adspersus 1 Red-necked Spurfowl Pternistis afer 1 Swainson's Spurfowl Pternistis swainsonii 1 Natal Spurfowl Pternistis natalensis 1 PODICIPEDIFORMES Grebes Podicipedidae Little Grebe Tachybaptus ruficollis 1 Black-necked Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 1 PHOENICOPTERIFORMES Flamingos Phoenicopteridae Greater Flamingo Phoenicopterus roseus 1 Lesser Flamingo - NT Phoeniconaias minor 1 CICONIIFORMES Storks Ciconiidae Yellow-billed Stork Mycteria ibis 1 Eagle-Eye Tours African Openbill Anastomus lamelligerus 1 Woolly-necked Stork Ciconia episcopus 1 Marabou Stork Leptoptilos crumenifer 1 PELECANIFORMES Ibises, Spoonbills Threskiornithidae African Sacred Ibis Threskiornis aethiopicus 1 Hadada Ibis Bostrychia -

1-Day Norfolk Winter Birding Tour – Birding the Norfolk Coast

1-DAY NORFOLK WINTER BIRDING TOUR – BIRDING THE NORFOLK COAST 01 NOVEMBER – 31 MARCH Snow Bunting winter on the Norfolk coast in sporadic flocks. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY UK 1-day tour: Norfolk Coast in Winter Our 1-day coastal Norfolk winter tour will take in the fabulous coastline of the county in its most dramatic form and connect with many of the special birds that make this part of the United Kingdom (UK) their home during this season. We will begin our tour at 9am and finish the day around dusk (times will vary slightly through the winter period). The North Norfolk coast is a popular and busy place, with birders and other tourists gravitating to several well-known sites. We will see a similar set of species to those possible at these well-known sites but will hopefully enjoy our birds with less people around. Our tour meeting point is at Thornham Harbour, with the first part of the tour expected to take around three hours. From our meeting point we will first explore the immediate area where we will find wading birds such as Common Redshank, Eurasian Curlew, Common Snipe, Eurasian Oystercatcher, and Grey Plover. We may also come across the delicate Twite as well as European Rock Pipit which both spend the winter in this sheltered spot. We will then make our way along the sea wall as far as the coastal dunes. Along the route we will look for more waders as we scan the expansive saltmarsh. Here we will come across vast flocks of Pink-footed Geese and Brant (Dark-bellied Brent) Geese, flocks of Eurasian Wigeon and Eurasian Teal, and mixed finch flocks containing European Goldfinch, Common Linnet, and perhaps more Twite. -

1-Day Norfolk Coast Winter Birding Tour

1-DAY NORFOLK COAST WINTER BIRDING TOUR NOVEMBER – MARCH Western Marsh Harrier will be a near-constant feature of our tour. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY UK 1-day tour: Norfolk Coast in Winter Our 1-day coastal Norfolk winter tour will take in the fabulous coastline of the county in its most dramatic form and connect with many of the special birds that make this part of the United Kingdom their home during this season. We will begin our tour at 9am and finish the day around dusk (times will vary slightly through the winter period). The North Norfolk coast is a popular and busy place, with birders and other tourists gravitating to several well-known sites. We will see a similar set of species to those possible at these well-known sites but will hopefully enjoy our birds with less people around. Our tour meeting point is at Thornham Harbour, with the first part of the tour expected to take around three hours. From our meeting point we will first explore the immediate area where we will find wading birds such as Common Redshank, Eurasian Curlew, Common Snipe, Eurasian Oystercatcher, and Grey Plover. We may also come across the delicate Twite as well as Eurasian Rock Pipit which both spend the winter in this sheltered spot. We will then make our way along the sea wall as far as the coastal dunes. Along the route we will look for more waders as we scan the expansive saltmarsh. Here we will come across vast flocks of Pink-footed Geese and Brant (Dark-bellied Brent) Geese, flocks of Eurasian Wigeon and Eurasian Teal, and mixed finch flocks containing European Goldfinch, Common Linnet, and perhaps more Twite. -

Coos, Booms, and Hoots: the Evolution of Closed-Mouth Vocal Behavior in Birds

ORIGINAL ARTICLE doi:10.1111/evo.12988 Coos, booms, and hoots: The evolution of closed-mouth vocal behavior in birds Tobias Riede, 1,2 Chad M. Eliason, 3 Edward H. Miller, 4 Franz Goller, 5 and Julia A. Clarke 3 1Department of Physiology, Midwestern University, Glendale, Arizona 85308 2E-mail: [email protected] 3Department of Geological Sciences, The University of Texas at Austin, Texas 78712 4Department of Biology, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador A1B 3X9, Canada 5Department of Biology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City 84112, Utah Received January 11, 2016 Accepted June 13, 2016 Most birds vocalize with an open beak, but vocalization with a closed beak into an inflating cavity occurs in territorial or courtship displays in disparate species throughout birds. Closed-mouth vocalizations generate resonance conditions that favor low-frequency sounds. By contrast, open-mouth vocalizations cover a wider frequency range. Here we describe closed-mouth vocalizations of birds from functional and morphological perspectives and assess the distribution of closed-mouth vocalizations in birds and related outgroups. Ancestral-state optimizations of body size and vocal behavior indicate that closed-mouth vocalizations are unlikely to be ancestral in birds and have evolved independently at least 16 times within Aves, predominantly in large-bodied lineages. Closed-mouth vocalizations are rare in the small-bodied passerines. In light of these results and body size trends in nonavian dinosaurs, we suggest that the capacity for closed-mouth vocalization was present in at least some extinct nonavian dinosaurs. As in birds, this behavior may have been limited to sexually selected vocal displays, and hence would have co-occurred with open-mouthed vocalizations. -

Simplified-ORL-2019-5.1-Final.Pdf

The Ornithological Society of the Middle East, the Caucasus and Central Asia (OSME) The OSME Region List of Bird Taxa, Part F: Simplified OSME Region List (SORL) version 5.1 August 2019. (Aligns with ORL 5.1 July 2019) The simplified OSME list of preferred English & scientific names of all taxa recorded in the OSME region derives from the formal OSME Region List (ORL); see www.osme.org. It is not a taxonomic authority, but is intended to be a useful quick reference. It may be helpful in preparing informal checklists or writing articles on birds of the region. The taxonomic sequence & the scientific names in the SORL largely follow the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) List at www.worldbirdnames.org. We have departed from this source when new research has revealed new understanding or when we have decided that other English names are more appropriate for the OSME Region. The English names in the SORL include many informal names as denoted thus '…' in the ORL. The SORL uses subspecific names where useful; eg where diagnosable populations appear to be approaching species status or are species whose subspecies might be elevated to full species (indicated by round brackets in scientific names); for now, we remain neutral on the precise status - species or subspecies - of such taxa. Future research may amend or contradict our presentation of the SORL; such changes will be incorporated in succeeding SORL versions. This checklist was devised and prepared by AbdulRahman al Sirhan, Steve Preddy and Mike Blair on behalf of OSME Council. Please address any queries to [email protected]. -

Proposals 2018-C

AOS Classification Committee – North and Middle America Proposal Set 2018-C 1 March 2018 No. Page Title 01 02 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae 02 10 Split Yellow Warbler (Setophaga petechia) into two species 03 25 Revise the classification and linear sequence of the Tyrannoidea (with amendment) 04 39 Split Cory's Shearwater (Calonectris diomedea) into two species 05 42 Split Puffinus boydi from Audubon’s Shearwater P. lherminieri 06 48 (a) Split extralimital Gracula indica from Hill Myna G. religiosa and (b) move G. religiosa from the main list to Appendix 1 07 51 Split Melozone occipitalis from White-eared Ground-Sparrow M. leucotis 08 61 Split White-collared Seedeater (Sporophila torqueola) into two species (with amendment) 09 72 Lump Taiga Bean-Goose Anser fabalis and Tundra Bean-Goose A. serrirostris 10 78 Recognize Mexican Duck Anas diazi as a species 11 87 Transfer Loxigilla portoricensis and L. violacea to Melopyrrha 12 90 Split Gray Nightjar Caprimulgus indicus into three species, recognizing (a) C. jotaka and (b) C. phalaena 13 93 Split Barn Owl (Tyto alba) into three species 14 99 Split LeConte’s Thrasher (Toxostoma lecontei) into two species 15 105 Revise generic assignments of New World “grassland” sparrows 1 2018-C-1 N&MA Classification Committee pp. 87-105 Adopt (a) a revised linear sequence and (b) a subfamily classification for the Accipitridae Background: Our current linear sequence of the Accipitridae, which places all the kites at the beginning, followed by the harpy and sea eagles, accipiters and harriers, buteonines, and finally the booted eagles, follows the revised Peters classification of the group (Stresemann and Amadon 1979). -

South Africa: the Southwestern Cape & Kruger August 17–September 1, 2018

SOUTH AFRICA: THE SOUTHWESTERN CAPE & KRUGER AUGUST 17–SEPTEMBER 1, 2018 Leopard LEADER: PATRICK CARDWELL LIST COMPILED BY: PATRICK CARDWELL VICTOR EMANUEL NATURE TOURS, INC. 2525 WALLINGWOOD DRIVE, SUITE 1003 AUSTIN, TEXAS 78746 WWW.VENTBIRD.COM SOUTH AFRICA: THE SOUTHWESTERN CAPE & KRUGER AUGUST 17–SEPTEMER 1, 2018 By Patrick Cardwell Our tour started in the historical gardens of the Alphen Hotel located in the heart of the Constantia Valley, with vineyards dating back to 1652 with the arrival of Jan van Riebeeck, the first Governor of the Cape. Surrounded by aging oak and poplar trees, this Heritage Site hotel is perfectly situated as a central point within the more rural environs of Cape Town, directly below the towering heights of Table Mountain and close to the internationally acclaimed botanical gardens of Kirstenbosch. DAY 1 A dramatic change in the prevailing weather pattern dictated a ‘switch’ between scheduled days in the itinerary to take advantage of a window of relatively calm sea conditions ahead of a cold front moving in across the Atlantic from the west. Our short drive to the harbor followed the old scenic road through the wine lands and over Constantia Nek to the picturesque and well-wooded valley of Hout (Wood) Bay, so named by the Dutch settlers for the abundance of old growth yellow wood trees that were heavily exploited during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Our skipper was on standby to welcome us on board a stable sport fishing boat with a wraparound gunnel, ideal for all-round pelagic seabird viewing and photographic opportunity in all directions. -

Do Dietary Shifts in Barn Owls Result from Rapid Farming Intensification?

Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 230 (2016) 42–46 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment journa l homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/agee Frogs taste nice when there are few mice: Do dietary shifts in barn owls result from rapid farming intensification? a, b Karina Hodara *, Santiago L. Poggio a Departamento de Métodos Cuantitativos y Sistemas de Información, Facultad de Agronomía, Universidad de Buenos Aires, Av. San Martín 4453 (C1417DSE), Buenos Aires, Argentina b IFEVA/Universidad de Buenos Aires/CONICET, Departamento de Producción Vegetal, Facultad de Agronomía, Av. San Martín 4453 (C1417DSE), Buenos Aires, Argentina A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Article history: Received 26 November 2015 Biodiversity ecosystem services in agroecosystems are negatively affected by farmland homogenisation Received in revised form 13 May 2016 due to intensive agriculture. The Pampas, an important worldwide region producing commodity crops, Accepted 22 May 2016 have been greatly homogenised with the expansion no-tillage and herbicide-tolerant transgenic Available online 10 June 2016 soybeans since the 1990s. Here, we tested the hypothesis of that dietary changes in barn owls will be associated with the loss of semi-natural habitats derived from farming intensification. We characterised Keywords: the dietary habits of western barn owls by analysing their pellets between two sampling periods (2004– Agricultural intensification 2005 and 2010–2012). We also assessed the habitat loss due to cropping intensification through fencerow Agroecosystems removal and pasture conversion to annual crops during the same period. We observed that barn owls Biodiversity shifted from eating mostly rodents in the first sampling period to eating a higher proportion of anurans in Land-use change the second sampling period. -

Owls of Southern Africa: Custom Birding Tours in Namibia, Botswana and South Africa

The twelve owls of southern Africa: custom birding tours in Namibia, Botswana and South Africa We see Pel’s Fishing Owl in quite a number of African countries, but Botswana and Namibia are the most reliable countries for sightings of this magnificent bird. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | ITINERARY Owls of Namibia, Botswana and South Africa We run tailor-made birding tours targeting all twelve of southern Africa’s owl species. Please do kindly peruse the information below and let us know if you want us to arrange a tour of any length to see these magnificent birds. A 12- to 15-day trip is needed if you want a realistic chance of seeing all twelve owl species, but we can arrange shorter trips (even just half or full day tours) to target just a couple of them. For example, if you find yourself in Johannesburg, we can actually find some of the most amazing species given just a day. It should also be noted that a couple of our set departure tours, especially our Namibia/Okavango/Victoria Falls trip each November, are brilliant for these owls, along with so many other birds and mammals, if you enjoy the small group experience, rather than a private, bespoke tour. Pel’s Fishing Owl is one of the most charismatic birds in Africa. This massive owl can be difficult to locate, but the Okavango Delta of Botswana boasts an unusually high density of this species and we almost invariably see it on our trips there. We usually find this hefty, ginger owl at its daytime roosts during boat trips along the Okavango channels, but we sometimes also look for it during walks through riverine forest, often on the well-wooded islands within this vast inland delta. -

Northern South Africa Trip Report Private Tour

NORTHERN SOUTH AFRICA TRIP REPORT PRIVATE TOUR 31 OCTOBER – 5 NOVEMBER 2017 By Dylan Vasapolli The rare Taita Falcon (Falco fasciinucha) showed well. www.birdingecotours.com [email protected] 2 | TRIP REPORT Northern South Africa November 2017 Overview This short tour was an extension to northern South Africa for a private client, following our set- departure South Africa tours to the Western Cape and Subtropical South Africa. The primary goal was to target species occurring in northern South Africa that are absent/uncommon elsewhere in the country and/or any species missed on the set-departure South Africa tours. This short tour began and ended in Johannesburg and saw us transiting northwards first to the rich thornveld of the Zaagkuilsdrift Road, followed by the montane forests of the Magoebaskloof hills before visiting the moist grasslands and broad-leaved woodlands found in north-eastern Gauteng. Day 1, October 31. Johannesburg Following the conclusion of our set-departure Subtropical South Africa tour earlier in the day I met up with James, who would be joining this post-tour extension, in the early evening. We headed for dinner and, following dinner, drove south of Johannesburg to search for African Grass Owl. We arrived on site and began working the region. We enjoyed excellent views of a number of Marsh Owls, along with Spotted Thick-knee, but drew a blank on the grass owl for most of our time. But at our last stop we had success and saw a single African Grass Owl come in, although it remained distant and did leave us wanting more. -

THE BRITISH LIST the Official List of Bird Species Recorded in Britain

THE BRITISH LIST The official list of bird species recorded in Britain This document summarises the Ninth edition of the British List (BOU, 2017. Ibis 160: 190-240) and subsequent changes to the List included in BOURC Reports and announcements (bou.org.uk/british-list/bourc-reports-and- papers/). Category A, B, C species Total no. of species on the British List (Cats A, B, C) = 627 at 13 August 2021 Category A 609 • Category B 8 • Category C 10 Other categories see p.13. The list below includes both the vernacular name used by British ornithologists and the IOC World Bird List international English name (see www.worldbirdnames.org) where these are different to the English vernacular name. British (English) IOC World Bird List Scientific name Category vernacular name international English name Brent Goose Brant Goose Branta bernicla AE Red-breasted Goose † Branta ruficollis AE* Canada Goose ‡ Branta canadensis AC2E* Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis AC2E* Cackling Goose † Branta hutchinsii AE Snow Goose Anser caerulescens AC2E* Greylag Goose Anser anser AC2C4E* Taiga Bean Goose Anser fabalis AE* Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus AE* Tundra Bean Goose Anser serrirostris AE White-fronted Goose Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons AE* Lesser White-fronted Goose † Anser erythropus AE* Mute Swan Cygnus olor AC2 Bewick’s Swan ‡ Tundra Swan Cygnus columbianus AE Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus AE* Egyptian Goose Alopochen aegyptiaca C1C5E* Shelduck Common Shelduck Tadorna tadorna A Ruddy Shelduck † Tadorna ferruginea BDE* Mandarin Duck Aix