Multiple Levels of Cyclin Specificity in Cell-Cycle Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitosis Vs. Meiosis

Mitosis vs. Meiosis In order for organisms to continue growing and/or replace cells that are dead or beyond repair, cells must replicate, or make identical copies of themselves. In order to do this and maintain the proper number of chromosomes, the cells of eukaryotes must undergo mitosis to divide up their DNA. The dividing of the DNA ensures that both the “old” cell (parent cell) and the “new” cells (daughter cells) have the same genetic makeup and both will be diploid, or containing the same number of chromosomes as the parent cell. For reproduction of an organism to occur, the original parent cell will undergo Meiosis to create 4 new daughter cells with a slightly different genetic makeup in order to ensure genetic diversity when fertilization occurs. The four daughter cells will be haploid, or containing half the number of chromosomes as the parent cell. The difference between the two processes is that mitosis occurs in non-reproductive cells, or somatic cells, and meiosis occurs in the cells that participate in sexual reproduction, or germ cells. The Somatic Cell Cycle (Mitosis) The somatic cell cycle consists of 3 phases: interphase, m phase, and cytokinesis. 1. Interphase: Interphase is considered the non-dividing phase of the cell cycle. It is not a part of the actual process of mitosis, but it readies the cell for mitosis. It is made up of 3 sub-phases: • G1 Phase: In G1, the cell is growing. In most organisms, the majority of the cell’s life span is spent in G1. • S Phase: In each human somatic cell, there are 23 pairs of chromosomes; one chromosome comes from the mother and one comes from the father. -

Polo-Like Kinase 1: Target and Regulator of Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome–Dependent Proteolysis Frank Eckerdt1 and Klaus Strebhardt2

Review Polo-Like Kinase 1: Target and Regulator of Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome–Dependent Proteolysis Frank Eckerdt1 and Klaus Strebhardt2 1Department of Pharmacology, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Denver, Colorado and 2Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Medical School, J.W. Goethe-University, Frankfurt, Germany Abstract to the regulation of the APC/C, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that is Polo-like kinase 1 (Plk1) is a key regulator of progression responsible for the timely destruction of various mitotic proteins, through mitosis. Although Plk1 seems to be dispensable for thereby regulating chromosome segregation, exit from mitosis, entry into mitosis, its role in spindle formation and exit from and a stable subsequent G1 phase (3).The APC/C is first activated by the ancillary protein Cdc20, targeting proteins containing a mitosis is crucial. Recent evidence suggests that a major role Cdc20 of Plk1 in exit from mitosis is the regulation of inhibitors of destruction box (D box), like securin.Once APC/C has the anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome (APC/C), such as initiated mitotic exit, Cdc20 itself is degraded and is replaced by Cdh1, allowing the degradation of a wider spectrum of substrates. the early mitotic inhibitor 1 (Emi1) and spindle checkpoint Cdh1 proteins. Thus, Plk1 and the APC/C control mitotic regulators The APC/C complex targets not only D box–containing proteins but also proteins exhibiting a KEN box and/or an A box by both phosphorylation and targeted ubiquitylation to Cdh1 ensure the fidelity of chromosome separation at the meta- (e.g., cyclin B1 and Aurora A). Plk1 itself is an APC/C target. -

List, Describe, Diagram, and Identify the Stages of Meiosis

Meiosis and Sexual Life Cycles Objective # 1 In this topic we will examine a second type of cell division used by eukaryotic List, describe, diagram, and cells: meiosis. identify the stages of meiosis. In addition, we will see how the 2 types of eukaryotic cell division, mitosis and meiosis, are involved in transmitting genetic information from one generation to the next during eukaryotic life cycles. 1 2 Objective 1 Objective 1 Overview of meiosis in a cell where 2N = 6 Only diploid cells can divide by meiosis. We will examine the stages of meiosis in DNA duplication a diploid cell where 2N = 6 during interphase Meiosis involves 2 consecutive cell divisions. Since the DNA is duplicated Meiosis II only prior to the first division, the final result is 4 haploid cells: Meiosis I 3 After meiosis I the cells are haploid. 4 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ Chromosomes condense. Because of replication during interphase, each chromosome consists of 2 sister chromatids joined by a centromere. ¾ Synapsis – the 2 members of each homologous pair of chromosomes line up side-by-side to form a tetrad consisting of 4 chromatids: 5 6 1 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Prophase I: ¾ During synapsis, sometimes there is an exchange of homologous parts between non-sister chromatids. This exchange is called crossing over. 7 8 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis (2N=6) Prophase I: ¾ the spindle apparatus begins to form. ¾ the nuclear membrane breaks down: Prophase I 9 10 Objective 1, Stages of Meiosis Objective 1, 4 Possible Metaphase I Arrangements: Metaphase I: ¾ chromosomes line up along the equatorial plate in pairs, i.e. -

Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Review Anaphase Bridges: Not All Natural Fibers Are Healthy Alice Finardi 1, Lucia F. Massari 2 and Rosella Visintin 1,* 1 Department of Experimental Oncology, IEO, European Institute of Oncology IRCCS, 20139 Milan, Italy; alice.fi[email protected] 2 The Wellcome Centre for Cell Biology, Institute of Cell Biology, School of Biological Sciences, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH9 3BF, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-02-5748-9859; Fax: +39-02-9437-5991 Received: 14 July 2020; Accepted: 5 August 2020; Published: 7 August 2020 Abstract: At each round of cell division, the DNA must be correctly duplicated and distributed between the two daughter cells to maintain genome identity. In order to achieve proper chromosome replication and segregation, sister chromatids must be recognized as such and kept together until their separation. This process of cohesion is mainly achieved through proteinaceous linkages of cohesin complexes, which are loaded on the sister chromatids as they are generated during S phase. Cohesion between sister chromatids must be fully removed at anaphase to allow chromosome segregation. Other (non-proteinaceous) sources of cohesion between sister chromatids consist of DNA linkages or sister chromatid intertwines. DNA linkages are a natural consequence of DNA replication, but must be timely resolved before chromosome segregation to avoid the arising of DNA lesions and genome instability, a hallmark of cancer development. As complete resolution of sister chromatid intertwines only occurs during chromosome segregation, it is not clear whether DNA linkages that persist in mitosis are simply an unwanted leftover or whether they have a functional role. -

Lte1 Promotes Mitotic Exit by Controlling the Localization of the Spindle Position Checkpoint Kinase Kin4

Lte1 promotes mitotic exit by controlling the localization of the spindle position checkpoint kinase Kin4 Jill E. Falk1, Leon Y. Chan1,2, and Angelika Amon3 David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139 This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2010. Contributed by Angelika Amon, May 17, 2011 (sent for review April 27, 2011) For a daughter cell to receive a complete genomic complement, it is The work by Adames et al. (13) proposed a model in which essential that the mitotic spindle be positioned accurately within the interactions between microtubules and the bud neck inhibit the cell. In budding yeast, a signaling system known as the spindle MEN, but how this could lead to Kin4 activation, if indeed Kin4 is position checkpoint (SPOC) monitors spindle position and regulates activated by spindle misposition, is not known. We previously the activity of the mitotic exit network (MEN), a GTPase signaling proposed a model termed the zone model, which posits that the pathway that promotes exit from mitosis. The protein kinase Kin4 budding yeast cell is divided into a MEN inhibitory zone in the is a central component of the spindle position checkpoint. Kin4 mother cell and a MEN activating zone in the daughter cell and primarily localizes to the mother cell and associates with spindle that a sensor, the GTPase Tem1, moves between them. Tem1 as well as most other components of the MEN reside at pole bodies (SPBs) located in the mother cell to inhibit MEN spindle pole bodies (SPBs; yeast centrosomes). -

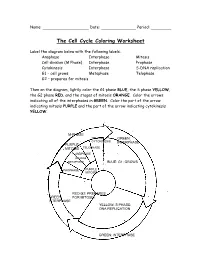

The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet

Name: Date: Period: The Cell Cycle Coloring Worksheet Label the diagram below with the following labels: Anaphase Interphase Mitosis Cell division (M Phase) Interphase Prophase Cytokinesis Interphase S-DNA replication G1 – cell grows Metaphase Telophase G2 – prepares for mitosis Then on the diagram, lightly color the G1 phase BLUE, the S phase YELLOW, the G2 phase RED, and the stages of mitosis ORANGE. Color the arrows indicating all of the interphases in GREEN. Color the part of the arrow indicating mitosis PURPLE and the part of the arrow indicating cytokinesis YELLOW. M-PHASE YELLOW: GREEN: CYTOKINESIS INTERPHASE PURPLE: TELOPHASE MITOSIS ANAPHASE ORANGE METAPHASE BLUE: G1: GROWS PROPHASE PURPLE MITOSIS RED:G2: PREPARES GREEN: FOR MITOSIS INTERPHASE YELLOW: S PHASE: DNA REPLICATION GREEN: INTERPHASE Use the diagram and your notes to answer the following questions. 1. What is a series of events that cells go through as they grow and divide? CELL CYCLE 2. What is the longest stage of the cell cycle called? INTERPHASE 3. During what stage does the G1, S, and G2 phases happen? INTERPHASE 4. During what phase of the cell cycle does mitosis and cytokinesis occur? M-PHASE 5. During what phase of the cell cycle does cell division occur? MITOSIS 6. During what phase of the cell cycle is DNA replicated? S-PHASE 7. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell grow? G1,G2 8. During what phase of the cell cycle does the cell prepare for mitosis? G2 9. How many stages are there in mitosis? 4 10. Put the following stages of mitosis in order: anaphase, prophase, metaphase, and telophase. -

System-Level Feedbacks Control Cell Cycle Progression

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector FEBS Letters 583 (2009) 3992–3998 journal homepage: www.FEBSLetters.org Review System-level feedbacks control cell cycle progression Orsolya Kapuy a, Enuo He a, Sandra López-Avilés b, Frank Uhlmann b, John J. Tyson c, Béla Novák a,* a Oxford Centre for Integrative Systems Biology, Department of Biochemistry, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3QU, UK b Chromosome Segregation Laboratory, Cancer Research UK London Research Institute, 44 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London WC2A 3PX, UK c Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA 24061, USA article info abstract Article history: Repetitive cell cycles, which are essential to the perpetuation of life, are orchestrated by an under- Received 25 June 2009 lying biochemical reaction network centered around cyclin-dependent protein kinases (Cdks) and Revised 27 July 2009 their regulatory subunits (cyclins). Oscillations of Cdk1/CycB activity between low and high levels Accepted 13 August 2009 during the cycle trigger DNA replication and mitosis in the correct order. Based on computational Available online 22 August 2009 modeling, we proposed that the low and the high kinase activity states are alternative stable steady Edited by Johan Elf states of a bistable Cdk-control system. Bistability is a consequence of system-level feedback (posi- tive and double-negative feedback signals) in the underlying control system. We have also argued that bistability underlies irreversible transitions between low and high Cdk activity states and Keywords: Cell cycle thereby ensures directionality of cell cycle progression. -

Regulation of Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Activity During Mitotic Exit and Maintenance of Genome Stability by P21, P27, and P107

Regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase activity during mitotic exit and maintenance of genome stability by p21, p27, and p107 Taku Chibazakura*†, Seth G. McGrew‡§, Jonathan A. Cooper§, Hirofumi Yoshikawa*, and James M. Roberts‡§ *Deparment of Bioscience, Tokyo University of Agriculture, 1-1-1 Sakuragaoka, Setagaya-ku, Tokyo 156-8502, Japan; and ‡Howard Hughes Medical Institute and §Division of Basic Sciences, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA 98019 Communicated by Robert N. Eisenman, Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, WA, February 4, 2004 (received for review October 28, 2003) To study the regulation of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) activity bind to and inactivate mitotic cyclin–CDK complexes (15, 16). during mitotic exit in mammalian cells, we constructed murine cell These CKIs accumulate and persist during mid-M-to-G1 phase ͞ lines that constitutively express a stabilized mutant of cyclin A until they are phosphorylated by Sic1 Rum1-resistant G1 cyclin- (cyclin A47). Even though cyclin A47 was expressed throughout CDKs, which initiates their ubiquitin-dependent degradation at mitosis and in G1 cells, its associated CDK activity was inactivated the G1-to-S phase transition (17–19). Thus, Sic1 and Rum1 after the transition from metaphase to anaphase. Cyclin A47 constitute a switch that controls the transition from a state of low associated with both p21 and p27 during mitotic exit, implicating CDK activity to that of high CDK activity, thereby regulating these proteins in CDK inactivation. However, cyclin A47 was fully mitotic exit and S phase entry. This parallels the activity of ؊/؊ ؊/؊ inhibited during the M-to-G1 transition in p21 p27 fibro- APC-Cdh1, and indeed these two pathways constitute redundant blasts. -

SAMBA, a Plant-Specific Anaphase-Promoting Complex/Cyclosome Regulator Is Involved in Early Development and A-Type Cyclin Stabilization Nubia B

SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome regulator is involved in early development and A-type cyclin stabilization Nubia B. Eloy, Nathalie Gonzalez, Jelle van Leene, Katrien Maleux, Hannes Vanhaeren, Liesbeth de Milde, Stijn Dhondt, Leen Vercruysse, Erwin Witters, Raphaël Mercier, et al. To cite this version: Nubia B. Eloy, Nathalie Gonzalez, Jelle van Leene, Katrien Maleux, Hannes Vanhaeren, et al.. SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/cyclosome regulator is involved in early de- velopment and A-type cyclin stabilization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , National Academy of Sciences, 2012, 109 (34), pp.13853 - 13858. 10.1073/pnas.1211418109. hal-01190736 HAL Id: hal-01190736 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01190736 Submitted on 29 May 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. SAMBA, a plant-specific anaphase-promoting complex/ cyclosome regulator is involved in early development and A-type cyclin stabilization Nubia B. Eloya,b, Nathalie Gonzaleza,b, Jelle Van Leenea,b, Katrien Maleuxa,b, Hannes Vanhaerena,b, Liesbeth De Mildea,b, Stijn Dhondta,b, Leen Vercruyssea,b, Erwin Wittersc,d,e, Raphaël Mercierf, Laurence Cromerf, Gerrit T. -

A Mathematical Model of Mitotic Exit in Budding Yeast: the Role of Polo Kinase

A Mathematical Model of Mitotic Exit in Budding Yeast: The Role of Polo Kinase Baris Hancioglu*¤, John J. Tyson Department of Biological Sciences, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia, United States of America Abstract Cell cycle progression in eukaryotes is regulated by periodic activation and inactivation of a family of cyclin–dependent kinases (Cdk’s). Entry into mitosis requires phosphorylation of many proteins targeted by mitotic Cdk, and exit from mitosis requires proteolysis of mitotic cyclins and dephosphorylation of their targeted proteins. Mitotic exit in budding yeast is known to involve the interplay of mitotic kinases (Cdk and Polo kinases) and phosphatases (Cdc55/PP2A and Cdc14), as well as the action of the anaphase promoting complex (APC) in degrading specific proteins in anaphase and telophase. To understand the intricacies of this mechanism, we propose a mathematical model for the molecular events during mitotic exit in budding yeast. The model captures the dynamics of this network in wild-type yeast cells and 110 mutant strains. The model clarifies the roles of Polo-like kinase (Cdc5) in the Cdc14 early anaphase release pathway and in the G-protein regulated mitotic exit network. Citation: Hancioglu B, Tyson JJ (2012) A Mathematical Model of Mitotic Exit in Budding Yeast: The Role of Polo Kinase. PLoS ONE 7(2): e30810. doi:10.1371/ journal.pone.0030810 Editor: Michael Lichten, National Cancer Institute, United States of America Received October 8, 2011; Accepted December 21, 2011; Published February 23, 2012 Copyright: ß 2012 Hancioglu, Tyson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. -

Meiosis I and Meiosis II; Life Cycles

Meiosis I and Meiosis II; Life Cycles Meiosis functions to reduce the number of chromosomes to one half. Each daughter cell that is produced will have one half as many chromosomes as the parent cell. Meiosis is part of the sexual process because gametes (sperm, eggs) have one half the chromosomes as diploid (2N) individuals. Phases of Meiosis There are two divisions in meiosis; the first division is meiosis I: the number of cells is doubled but the number of chromosomes is not. This results in 1/2 as many chromosomes per cell. The second division is meiosis II: this division is like mitosis; the number of chromosomes does not get reduced. The phases have the same names as those of mitosis. Meiosis I: prophase I (2N), metaphase I (2N), anaphase I (N+N), and telophase I (N+N) Meiosis II: prophase II (N+N), metaphase II (N+N), anaphase II (N+N+N+N), and telophase II (N+N+N+N) (Works Cited See) *3 Meiosis I (Works Cited See) *1 1. Prophase I Events that occur during prophase of mitosis also occur during prophase I of meiosis. The chromosomes coil up, the nuclear membrane begins to disintegrate, and the centrosomes begin moving apart. The two chromosomes may exchange fragments by a process called crossing over. When the chromosomes partially separate in late prophase, until they separate during anaphase resulting in chromosomes that are mixtures of the original two chromosomes. 2. Metaphase I Bivalents (tetrads) become aligned in the center of the cell and are attached to spindle fibers. -

A Novel Function for HSF1-Induced Mitotic Exit Failure and Genomic Instability Through Direct Interaction Between HSF1 and Cdc20

Oncogene (2008) 27, 2999–3009 & 2008 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9232/08 $30.00 www.nature.com/onc ORIGINAL ARTICLE A novel function for HSF1-induced mitotic exit failure and genomic instability through direct interaction between HSF1 and Cdc20 YJ Lee1, HJ Lee1, JS Lee2, D Jeoung3, CM Kang1, S Bae1, SJ Lee2, SH Kwon4, D Kang4 and YS Lee1 1Division of Radiation Effect, Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, Seoul, Republic of Korea; 2Division of Radiation Cancer Research, Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Sciences, Seoul, Korea; 3College of Natural Sciences, Kangwon National University, Chunchon, Korea and 4Korea Basic Science Institute, Chunchon Center, Chunchon, Korea Although heat-shock factor (HSF) 1 is a known highly aneuploid, however, the molecular mechanisms transcriptional factor of heat-shock proteins, other path- underlying the development of aneuploidy have not wayslike production of aneuploidy and increasedprotein been fully defined, although mutations in mitotic stability of cyclin B1 have been proposed. In the present checkpoint genes have been identified in a subset of study, the regulatory domain of HSF1 (amino-acid human cancers and cell lines (Lengauer et al., 1997; sequence 212–380) was found to interact directly with Cahill et al., 1998). the amino-acid sequence 106–171 of Cdc20. The associa- Enhanced heat-shock protein (HSP) expression in tion between HSF1 and Cdc20 inhibited the interaction response to various stimuli is regulated by heat-shock between Cdc27 and Cdc20, the phosphorylation of Cdc27 factors (HSFs), the functional relevance of which is now and the ubiquitination activity of anaphase-promoting emerging.