The Cygnus Superbubble Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BRAS Newsletter August 2013

www.brastro.org August 2013 Next meeting Aug 12th 7:00PM at the HRPO Dark Site Observing Dates: Primary on Aug. 3rd, Secondary on Aug. 10th Photo credit: Saturn taken on 20” OGS + Orion Starshoot - Ben Toman 1 What's in this issue: PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE....................................................................................................................3 NOTES FROM THE VICE PRESIDENT ............................................................................................4 MESSAGE FROM THE HRPO …....................................................................................................5 MONTHLY OBSERVING NOTES ....................................................................................................6 OUTREACH CHAIRPERSON’S NOTES .........................................................................................13 MEMBERSHIP APPLICATION .......................................................................................................14 2 PRESIDENT'S MESSAGE Hi Everyone, I hope you’ve been having a great Summer so far and had luck beating the heat as much as possible. The weather sure hasn’t been cooperative for observing, though! First I have a pretty cool announcement. Thanks to the efforts of club member Walt Cooney, there are 5 newly named asteroids in the sky. (53256) Sinitiere - Named for former BRAS Treasurer Bob Sinitiere (74439) Brenden - Named for founding member Craig Brenden (85878) Guzik - Named for LSU professor T. Greg Guzik (101722) Pursell - Named for founding member Wally Pursell -

Discovery of a Pulsar Wind Nebula Candidate in the Cygnus Loop

Discovery of a Pulsar Wind Nebula Candidate in the Cygnus Loop 2 3 S Satoru Katsuda" Hiroshi Tsunemi , Koji Mori , Hiroyuki Uchida" Robert Petre , Shin'ya 1 Yamada , and Thru Tamagawa' ABSTRACT We report on a discovery of a diffuse nebula containing a pointlike source in the southern blowout region of the Cygnus Loop supernova remnant, based on Suzaku and XMM-Newton observations. The X-ray spectra from the nebula and the pointlike source are well represented by an absorbed power-law model with photon indices of 2.2±0.1 and 1.6±0.2, respectively. The photon indices as well as the flux ratio of F nebula/ F po;.,li" ~ 4 lead us to propose that the system is a pulsar wind nebula, although pulsations have not yet been detected. If we attribute its origin to the Cygnus Loop supernova, then the 0.5- 8 keY luminosity of the nebula is computed to be 2.1xlo"' (d/MOpc)2ergss-" where d is the distance to the Loop. This implies a spin-down loss-energy E ~ 2.6 X 1035 (d/MOpc)2ergss-'. The location of the neutron star candidate, ~2° away from the geometric center of the Loop, implies a high transverse velocity of ~ 1850(8/2D ) (d/540pc) (t/lOkyr)- ' kms-" assuming the currently accepted age of the Cygnus Loop. Subject headings: ISM: individual objects (Cygnus Loop) - ISM: supernova remnants - pulsars: general - stars: neutron - stars: winds, outflows - X-rays: ISM 'RlKEN (The Institute of Physical and Chemical Research), 2-1 Hirosawa, Wako, Sailama 351-0198 2Department of EaTth and Space Science, Graduate School of Science, Osaka University, 1-1 Machikaneyama, Thyonaka, Osaka, 60-0043, Japan SDepartment of Applied Physics, Faculty of Engineering, University of Miyazaki, 1-1 Gakuen Klbana-dai Nishi, Miyazaki, 889-2192, Japan ' Department of PhysiCS, Kyoto University, Kitashirakawa-oiwake-clto, Sakyo, Kyoto 606-8502, J apan 'NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Code 662, Greenbelt MD 20771 - 2 - 1. -

A Synchrotron Superbubble in the IC 10 Galaxy: a Hypernova Remnant?

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–?? (2007) Printed 28 October 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) A synchrotron superbubble in the IC 10 Galaxy: a hypernova remnant? T. A. Lozinskaya1⋆ and A. V. Moiseev2 1Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Universitetskii pr. 13, Moscow, 119991 Russia 2Special Astrophysical Observatory, Nizhnii Arkhyz, Karachaevo-Cherkesia, 369167 Russia Accepted 2007 June 29. Received 2007 June; in original form 2007 June 4 ABSTRACT The nature of the synchrotron superbubble in the IC 10 galaxy is discussed using the results of our investigation of its ionized gas structure, kinematics, and emission spectrum from observations made with the 6-m telescope of the Special Astrophysical Observatory of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and based on our analysis of the radio emission of the region. The hypernova explosion is shown to be a more plausi- ble mechanism of the formation of the synchrotron superbubble compared with the earlier proposed model of multiple supernova explosions. A compact remnant of this hypernova may be identified with the well known X-ray binary X-1 – an accreting black hole. Key words: ISM: bubbles – ISM: kinematics and dynamics – supernova remnants galaxies: individual: IC 10. 1 INTRODUCTION. and observations with a scanning Fabry–Perot interferom- eter (FPI) in the Hα line. We report the detailed results The synchrotron superbubble in the IC 10 galaxy was discov- of our observations in a separate paper (Lozinskaya et al. ered by Yang & Skillman (1993). They associated it with the 2007). In this Letter we summarize the main results of these explosion of about ten supernovae. The synchrotron nature observations and the ensuing conclusions. -

XMM-Newton Observation of the Northeastern Limb of the Cygnus Loop Supernova Remnant

XMM-Newton Observation of the Northeastern Limb of the Cygnus Loop Supernova Remnant Norbert Nemes Graduate School of Science, Osaka University, 1-1 Machikaneyama-cho, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, Japan 04 February 2005 Osaka University Abstract We have observed the northeastern limb of the Cygnus Loop supernova remnant with the XMM-Newton observatory, as part of a 7-pointing campaign to map the remnant across its diameter. We performed medium sensitivity spatially resolved X-ray spectroscopy on the data in the 0.3-3.0 keV energy range, and for the first time we have detected C emission lines in our spectra. The background subtracted spectra were fitted with a single temperature absorbed non-equilibrium (VNEI) model. We created color maps and plotted the radial variation of the different parameters. We found that the heavy element abundances were depleted, but increase toward the edge of the remnant, exhibiting a jump structure near the northeastern edge of the field of view. The depletion suggests that the plasma in this region represents the shock heated ISM rather than the ejecta, while the radial increase of the elemental abundances seems to support the cavity explosion origin. The temperature decreases in the radial direction from 0:3keV to about 0:2keV , however, this ∼ ∼ decrease is not monotonic. There is a low temperature region in the part of the field of view closest to the center of the remnant, which is characterized by low abundances and high NH values. Another low temperature region characterized by low NH values but where the heavy element abundances suddenly jump to high values was found at the northeastern edge of the field of view. -

Pos(MULTIF15)020 Al

Suzaku Highlights of Supernova Remnants PoS(MULTIF15)020 Satoru Katsuda∗† Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), 3-1-1 Yoshinodai, Chuo, Sagamihara, Kanagawa 252-5210, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Hiroshi Tsunemi Department of Earth and Space Science, Osaka University, 1-1 Machikaneyama-cho, Toyonaka, Osaka 560-0043, Japan E-mail: [email protected] Suzaku was the Japanese 5th X-ray astronomy satellite operated from 2005 July 10 to 2015 Au- gust 26. Its key features are high-sensitivity wide-band X-ray spectroscopy available with both the X-ray imaging CCD cameras and the non-imaging collimated hard X-ray detector. A number of interesting scientific discoveries have been achieved in various fields. Among them, I will focus on results on supernova remnants. The topics in this paper include (1) revealing distributions of supernova ejecta, (2) establishing over-ionized plasmas by discoveries of radiative-recombination continua, (3) constraining progenitors of Type Ia SNRs from Mn/Cr and Ni/Fe line ratios, and (4) searching for X-ray counterparts from unidentified HESS sources. These results are of high sci- entific importance in physics of supernova explosions, non-equilibrium plasmas, and cosmic-ray acceleration. XI Multifrequency Behaviour of High Energy Cosmic Sources Workshop, 25-30 May 2015 Palermo, Italy ∗Speaker. †A footnote may follow. © c CopyrightCopyright owned owned by the author(s) under the terms of the Creative Creative Commons License Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International. http://pos.sissa.it/ Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). -

Hubble Revisits the Veil Nebula 2 April 2021

Image: Hubble revisits the Veil Nebula 2 April 2021 this stellar violence, the shockwaves and debris from the supernova sculpted the Veil Nebula's delicate tracery of ionized gas—creating a scene of surprising astronomical beauty. The Veil Nebula is also featured in Hubble's Caldwell Catalog, a collection of astronomical objects that have been imaged by Hubble and are visible to amateur astronomers in the night sky. Provided by NASA Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA, Z. Levay This image taken by the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope revisits the Veil Nebula, which was featured in a previous Hubble image release. In this image, new processing techniques have been applied, bringing out fine details of the nebula's delicate threads and filaments of ionized gas. To create this colorful image, observations were taken by Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 instrument using five different filters. The new post-processing methods have further enhanced details of emissions from doubly ionized oxygen (seen here in blues), ionized hydrogen, and ionized nitrogen (seen here in reds). The Veil Nebula lies around 2,100 light-years from Earth in the constellation of Cygnus (the Swan), making it a relatively close neighbor in astronomical terms. Only a small portion of the nebula was captured in this image. The Veil Nebula is the visible portion of the nearby Cygnus Loop, a supernova remnant formed roughly 10,000 years ago by the death of a massive star. That star—which was 20 times the mass of the Sun—lived fast and died young, ending its life in a cataclysmic release of energy. -

Monthly Observer's Challenge

MONTHLY OBSERVER'S CHALLENGE Compiled by: Roger Ivester, North Carolina & Sue French, New York September 2020 Report #140 The Veil Nebula in Cygnus Sharing Observations and Bringing Amateur Astronomers Together Introduction The purpose of the Observer's Challenge is to encourage the pursuit of visual observing. It's open to everyone who's interested, and if you're able to contribute notes, and/or drawings, we’ll be happy to include them in our monthly summary. Visual astronomy depends on what's seen through the eyepiece. Not only does it satisfy an innate curiosity, but it allows the visual observer to discover the beauty and the wonderment of the night sky. Before photography, all observations depended on what astronomers saw in the eyepiece, and how they recorded their observations. This was done through notes and drawings, and that's the tradition we're stressing in the Observer's Challenge. And for folks with an interest in astrophotography, your digital images and notes are just as welcome. The hope is that you'll read through these reports and become inspired to take more time at the eyepiece, study each object, and look for those subtle details that you might never have noticed before. This month's target The Veil Nebula has long been modeled as the remnant of a supernova explosion that occurred within an interstellar cavity created by the progenitor star. However, a recent study by Fesen, Weil, and Cisneros (2018MNRAS.481.1786F ) using multi-wavelength emission maps indicates that the large-scale structure of the Veil Nebula is due to interaction of the remnant with local interstellar clouds. -

A Basic Requirement for Studying the Heavens Is Determining Where In

Abasic requirement for studying the heavens is determining where in the sky things are. To specify sky positions, astronomers have developed several coordinate systems. Each uses a coordinate grid projected on to the celestial sphere, in analogy to the geographic coordinate system used on the surface of the Earth. The coordinate systems differ only in their choice of the fundamental plane, which divides the sky into two equal hemispheres along a great circle (the fundamental plane of the geographic system is the Earth's equator) . Each coordinate system is named for its choice of fundamental plane. The equatorial coordinate system is probably the most widely used celestial coordinate system. It is also the one most closely related to the geographic coordinate system, because they use the same fun damental plane and the same poles. The projection of the Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere is called the celestial equator. Similarly, projecting the geographic poles on to the celest ial sphere defines the north and south celestial poles. However, there is an important difference between the equatorial and geographic coordinate systems: the geographic system is fixed to the Earth; it rotates as the Earth does . The equatorial system is fixed to the stars, so it appears to rotate across the sky with the stars, but of course it's really the Earth rotating under the fixed sky. The latitudinal (latitude-like) angle of the equatorial system is called declination (Dec for short) . It measures the angle of an object above or below the celestial equator. The longitud inal angle is called the right ascension (RA for short). -

Breaching the Eddington Limit in the Most Massive, Most Luminous Stars

Mass Loss from (Hot) Massive Luminous Stars Stan Owocki Bartol Research Institute Department of Physics & Astronomy University of Delaware Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Massive Stars in the Whirlpool Galaxy Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Henize 70: LMC SuperBubble Wind-Blown Bubbles in ISM Some key scalings: Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Henize 70: LMC SuperBubble Wind-Blown Bubbles in ISM Some key scalings: WR wind bubble NGC 2359 Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Henize 70: LMC SuperBubble Wind-Blown Bubbles in ISM Some key scalings: WR wind bubble NGC 2359 Superbubble in the Large Magellanic Cloud Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Pistol Nebula Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Eta Carinae Wednesday, January 12, 2011 P-Cygni Line Profile Line-scattering in massive winds Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Observed wind line profiles Resonance line-scattering Recombination line O-star P-Cygni profile WR-star emission profile −v∞ +v −v∞ ∞ Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Basic Mass Loss Properties i 2 Mass Loss rate M = 4πρvr Terminal speed Velocity law v(r) v∞ 8 Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Massive-Star Mass Loss i M 1. OB Winds M ~ 10−9 − 10−6 yr v∞ 1000 − 3000 km / s – opt. thin τ c < 1 2. Wolf-Rayet Winds i M M ~ 10−6 − 10−5 yr – opt. thick τ c > 1 v∞ 1000 − 3000 km / s 3. Luminous Blue Variable (LBV) Eruptions i 1 −5 M -very opt. thick τ c M ~ 10 − 1 !! yr v∞ 50 − 1000 km / s Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Q: What can drive such extreme mass loss?? Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Q: What can drive such extreme mass loss?? A: The force of light! Wednesday, January 12, 2011 -

Modelling Supernova Remnant Kinematics and X-Ray Emission: Some Examples

Modelling Supernova Remnant kinematics and X-ray emission: Some Examples. Margarita Rosado Instituto de Astronomía UNAM Collaborators: • Pablo Velázquez, Ary Rodríguez González (ICN-UNAM) • Jorge Reyes Iturbide (IT Santiago Tianguistengo) • Patricia Ambrocio-Cruz (UAEH) • Mónica Sánchez-Cruces (ESFM-IPN) I. The Kinematics: By means of a FP Interferometer (i.e. the PUMA) One gets millions of Halpha or [SII] profiles over the field. From Valdez- Gutiérrez et al. 2001 OAN: San Pedro Mártir, B.C. Mexico PUMA INTERFEROMETER PUMA parameters - Detector CCD 1024x1024 – FP scanning steps 48 – Finesse 24 – Spectral resolution 47.3 km s-1 – Plate scale 0.59 arcsec pix -1 – Filters Hα [SII] – Central lambda a 6570 6720 – Interference order 330 332 – Free spectral range b 847 931 – Sampling step c 17.6 19.4 – Calibration line a Hα (6562.7) Ne (6717.04) a) in units of angstroms, b) in km s -1, c) in km s -1 channel -1 Doppler Effect Iso-velocity contours in our Galaxy Rotation curve of our Galaxy (also from Bland & Blitz ) The kinematics of SNRs is a powerful tool that we can use to estimate the DISTANCE, and other important parameters of those objects. The Galactic SNR CTB 109 and the quest for its distance: Radio Einstein X-rays continuum, and CO CO and HI From Gregory & Falman (1980), Tatematsu et al. (1987), Kothes et al. (2002, 2006) While in the optical: Hurford & Fesen (1995) Sánchez -Cruces et al. (2017) 2D [SII]/Hα line-ratios of the optical filaments è a radiative shock Typical [SII] velocity profiles of two regions: è SNR CTB 109 IS IN THE PERSEUS ARM è THIS SNR HOSTING A MAGNETAR HAS RATHER TYPICAL INITIAL ENERGY II. -

List of Bright Nebulae Primary I.D. Alternate I.D. Nickname

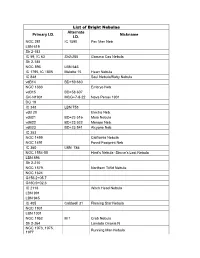

List of Bright Nebulae Alternate Primary I.D. Nickname I.D. NGC 281 IC 1590 Pac Man Neb LBN 619 Sh 2-183 IC 59, IC 63 Sh2-285 Gamma Cas Nebula Sh 2-185 NGC 896 LBN 645 IC 1795, IC 1805 Melotte 15 Heart Nebula IC 848 Soul Nebula/Baby Nebula vdB14 BD+59 660 NGC 1333 Embryo Neb vdB15 BD+58 607 GK-N1901 MCG+7-8-22 Nova Persei 1901 DG 19 IC 348 LBN 758 vdB 20 Electra Neb. vdB21 BD+23 516 Maia Nebula vdB22 BD+23 522 Merope Neb. vdB23 BD+23 541 Alcyone Neb. IC 353 NGC 1499 California Nebula NGC 1491 Fossil Footprint Neb IC 360 LBN 786 NGC 1554-55 Hind’s Nebula -Struve’s Lost Nebula LBN 896 Sh 2-210 NGC 1579 Northern Trifid Nebula NGC 1624 G156.2+05.7 G160.9+02.6 IC 2118 Witch Head Nebula LBN 991 LBN 945 IC 405 Caldwell 31 Flaming Star Nebula NGC 1931 LBN 1001 NGC 1952 M 1 Crab Nebula Sh 2-264 Lambda Orionis N NGC 1973, 1975, Running Man Nebula 1977 NGC 1976, 1982 M 42, M 43 Orion Nebula NGC 1990 Epsilon Orionis Neb NGC 1999 Rubber Stamp Neb NGC 2070 Caldwell 103 Tarantula Nebula Sh2-240 Simeis 147 IC 425 IC 434 Horsehead Nebula (surrounds dark nebula) Sh 2-218 LBN 962 NGC 2023-24 Flame Nebula LBN 1010 NGC 2068, 2071 M 78 SH 2 276 Barnard’s Loop NGC 2149 NGC 2174 Monkey Head Nebula IC 2162 Ced 72 IC 443 LBN 844 Jellyfish Nebula Sh2-249 IC 2169 Ced 78 NGC Caldwell 49 Rosette Nebula 2237,38,39,2246 LBN 943 Sh 2-280 SNR205.6- G205.5+00.5 Monoceros Nebula 00.1 NGC 2261 Caldwell 46 Hubble’s Var. -

Feedback by Massive Stars and the Emergence of Superbubbles

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. krause+2013_ESB_II_v10 c ESO 2018 January 3, 2018 Feedback by massive stars and the emergence of superbubbles II. X-ray properties Martin Krause1, 2,⋆, Roland Diehl1, 2, Hans Böhringer1, 2, Michael Freyberg1, and Daniel Lubos1 1 Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstr. 1, 85741 Garching, Germany 2 Excellence Cluster Universe, Technische Universität München, Boltzmannstrasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany Received March 24, 2014; accepted ? ABSTRACT Context. In a previous paper we investigated the energy transfer of massive stars to the interstellar medium as a function of time and the geometrical configuration of three massive stars via 3D-mesh-refining hydrodynamics simulations, following the complete evolution of the massive stars and their supernovae except non-thermal processes . Aims. In order to compare our results against observations we derive thermal X-ray properties of the interstellar medium from our simulations and compare them to observations of superbubbles in general, to the well-studied nearby Orion-Eridanus superbubble and to the diffuse soft X-ray emission of nearby galaxies. Methods. We analysed our ISM simulation results with the help of spectra for plasma temperatures between 0.1 and 10 keV and computed the spectral evolution and the spatio-temporal distribution of the hot gas. Results. Despite significant input of high temperature gas from supernovae and fast stellar winds, the resulting thermal X-ray spectra are generally very soft, with most of the emission well below 1 keV. We show that this is due to mixing triggered by resolved hydrodynamic instabilities. Supernovae enhance the X-ray luminosity of a superbubble by 1-2 orders of magnitude for a time span of about 0.1 Myr; longer if a supernova occurs in a larger superbubble and shorter in higher energy bands.