Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE EXPLORERS by Richard F. Pourade CHAPTER ONE: BEFORE

THE EXPLORERS By Richard F. Pourade CHAPTER ONE: BEFORE THE EXPLORERS San Diego was a well populated area before the first Spanish explorers arrived. The climate was wetter and perhaps warmer, and the land more wooded than now. The remnant of a great inland lake covered most of Imperial Valley. The San Diego River wandered back and forth over the broad delta it had formed between Point Loma and Old Town, alternately emptying into Mission Bay and San Diego Bay. The natural food supply was so abundant that the state as a whole supported an Indian population far greater than any equal area in the United States. The native population of the southern counties alone must have been at least 10,000. The early maps made of San Diego Bay by the Spanish explorers show the same general configuration as of today, except, of course, for the many changes in the shoreline made by dredging and filling in recent years. The maps, crudely drawn without proper surveys, vary considerably in detail. Thousands of years ago, in the late part of the Ice Age, Point Loma was an island, as were Coronado and North Island. Coronado used to be known as South Island. There was no bay, as we think of it now. A slightly curving coastline was protected by the three islands, of which, of course, Point Loma was by far the largest. What we now know as Crown Point in Mission Bay was a small peninsula projecting into the ocean. On the mainland, the San Diego and Linda Vista mesas were one continuous land mass. -

Naco Steering Committee Appointments Announced Finance

Leadership ♦ Research ♦ Advocacy ♦ Newsletter ♦ Speakers ♦ Counties ♦ Alliances ♦ Calendar ♦ Contact In the August 5, 2016, CSA Update: • NACo Steering Committee Appointments Announced • Finance Directors meet at GFOAz • 2016 Election: Early Voting Has Begun • CSA on the Road • ADWR: Church in Vicksburg in the West Basins Becomes Focal Point in Local Struggles Over Groundwater • This Week in Arizona History… • Upcoming NACo Webinar • Calendar NACo Steering Committee Appointments Announced The National Association of Counties (NACo) released their list of steering committee leadership appointments. 12 Arizona County Supervisors were appointed to NACo leadership positions by President Bryan Desloge, Leon County, Florida. Congratulations to the following Arizona leaders (alphabetical by county): · Supervisor Tom White (Apache) was appointed as a member to both the Veterans and Military Services Committee and the Rural Action Caucus. · Supervisor Liz Archuleta (Coconino) was appointed as a Vice-chair of the Programs and Services Standing Committee and as a member of the Resilient Counties Advisory Board. · Supervisor Matt Ryan (Coconino) was appointed as a member of the Veterans and Military Services Committee. · Supervisor Mandy Metzger (Coconino) was appointed as a member of both the Rural Action Caucus and the Veterans and Military Services Committee. · Supervisor Lena Fowler (Coconino) was appointed as a member of the Rural Action Caucus. · Supervisor Tommie Martin (Gila) was appointed as Chair of the Public Lands Steering Committee and as a member of the Rural Action Caucus. · Supervisor Steve Gallardo (Maricopa) was appointed as a member of the Large Urban County Caucus. · Supervisor Buster Johnson (Mohave) was appointed as a Vice-chair of the Information Technology Standing Committee. -

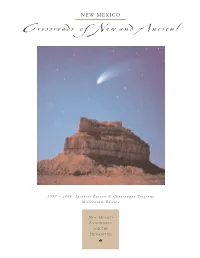

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Interview No. 282

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Combined Interviews Institute of Oral History 12-1976 Interview no. 282 George E. Barnhart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/interviews Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Interview with George E. Barnhart by Carlos Tapia, 1976, "Interview no. 282," Institute of Oral History, University of Texas at El Paso. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Oral History at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Combined Interviews by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOFTEXAS AT EL PASC INSTITUTEOFOR.AL HISTORY II.ITERVIEIdEE: GeorqeE. Barnhart INTERVIEI.IER: CarlosTaPia PROJECT: Class proiect DATEOF II'ITERVIEI'I: DecemberI 976 TERI''6OF USE: Unrestricted TAPENO.: 282 T:IAI'ISCRIPTI.iO.: 282 TRAIISCRISER: DATETRA|'ISCRIBED: BIOGRAPHICALSYiiOPSIS OF INTERVIEI'IEE: 01d-time E] Pasoresident. SUI{I}trRYOF I|'ITER\IIEI,I: j I ett and BioqraPhy;the MexicanRevol ution; Prohbi tion ; J'imGi JudgeRoy Bean' John|.lesleY Hardin; tf," O.pt.ssion; Worldl'lar II; 50 minutes I4 pages 'interview { Oral History with Mr- GeorgeE. Barnhart, interviewedby Carlos Tapia in December1976" ) T: Mr. Barnhar{wherewere you born and when? B: hlestBends, Okl ahoma. T: Whatwas the date? B: We]l, it's supposedto be February24, 1896. Theydidn't keepany records back in themdays. I had to checkback and I got two or three different [dates, but] that's the one I usedto look for a job. -

Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century

Hannigan 1 “Overrun All This Country…” Two New Mexican Lives Through the Nineteenth Century “José Francisco Chavez.” Library of Congress website, “General Nicolás Pino.” Photograph published in Ralph Emerson Twitchell, The History of the Military July 15 2010, https://www.loc.gov/rr/hispanic/congress/chaves.html Occupation of the Territory of New Mexico, 1909. accessed March 16, 2018. Isabel Hannigan Candidate for Honors in History at Oberlin College Advisor: Professor Tamika Nunley April 20, 2018 Hannigan 2 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2 I. “A populace of soldiers”, 1819 - 1848. ............................................................................................... 10 II. “May the old laws remain in force”, 1848-1860. ............................................................................... 22 III. “[New Mexico] desires to be left alone,” 1860-1862. ...................................................................... 31 IV. “Fighting with the ancient enemy,” 1862-1865. ............................................................................... 53 V. “The utmost efforts…[to] stamp me as anti-American,” 1865 - 1904. ............................................. 59 Conclusion .............................................................................................................................................. 72 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................ -

Arizona Historic Preservation Plan 2000

ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONAHistoric Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 ARIZONASTATEPARKSBOARD Chair Executive Staff Walter D. Armer, Jr. Kenneth E. Travous Benson Executive Director Members Renée E. Bahl Suzanne Pfister Assistant Director Phoenix Jay Ream Joseph H. Holmwood Assistant Director Mesa Mark Siegwarth John U. Hays Assistant Director Yarnell Jay Ziemann Sheri Graham Assistant Director Sedona Vernon Roudebush Safford Michael E. Anable State Land Commissioner ARIZONA Historic Preservation Plan UPDATE 2000 StateHistoricPreservationOffice PartnershipsDivision ARIZONASTATEPARKS 5 6 StateHistoricPreservationOffice 3 4 PartnershipsDivision 7 ARIZONASTATEPARKS 1300WestWashington 8 Phoenix,Arizona85007 1 Tel/TTY:602-542-4174 2 http://www.pr.state.az.us ThisPlanUpdatewasapprovedbythe 9 11 ArizonaStateParksBoardonMarch15,2001 Photographsthroughoutthis 10 planfeatureviewsofhistoric propertiesfoundwithinArizona 6.HomoloviRuins StateParksincluding: StatePark 1.YumaCrossing 7.TontoNaturalBridge9 StateHistoricPark StatePark 2.YumaTerritorialPrison 8.McFarland StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark 3.Jerome 9.TubacPresidio StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark Coverphotographslefttoright: 4.FortVerde 10.SanRafaelRanch StateHistoricPark StatePark FortVerdeStateHistoricPark TubacPresidioStateHistoricPark 5.RiordanMansion 11.TombstoneCourthouse McFarlandStateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark StateHistoricPark YumaTerritorialPrisonStateHistoricPark RiordanMansionStateHistoricPark Tombstone Courthouse Contents Introduction 1 Arizona’s -

Pattie Party Memorial Plaque Records MS 31

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8n0158f No online items Guide to the Pattie Party Memorial Plaque Records MS 31 Finding aid prepared by Katrina White Collection processed as part of grant project supported by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) with generous funding from The Andrew Mellon Foundation. San Diego History Center Document Collection 1649 El Prado, Suite 3 San Diego, CA, 92101 619-232-6203 May 22, 2012 Guide to the Pattie Party MS 31 1 Memorial Plaque Records MS 31 Title: Pattie Party Memorial Plaque Records Identifier/Call Number: MS 31 Contributing Institution: San Diego History Center Document Collection Language of Material: English Physical Description: 0.25 Linear feet(1 box) Date (inclusive): 1906-1949 Abstract: Collection contains correspondence and other documents pertaining to the Pattie Party, Pattie Party descendants and the plaque commemorating Sylvester Pattie and party on Presidio Hill in San Diego. creator: San Diego Historical Society. Conditions Governing Access This collection is open for research. Conditions Governing Use The San Diego History Center (SDHC) holds the copyright to any unpublished materials. SDHC Library regulations do apply. Processing Information Collection processed by Katrina White on May 22, 2012. Collection processed as part of grant project supported by the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) with generous funding from The Andrew Mellon Foundation. Preferred Citation Pattie Party Memorial Plaque Records, MS 31, San Diego History Center Document Collection, San Diego, CA. Biographical / Historical Notes Sylvester Pattie and his son, James Ohio Pattie, led a trapping expedition to New Mexico in 1824. In 1827, the Patties, along with Nathaniel Pryor, Richard Laughlin, William Pope, Isaac Slover, Jesse Ferguston, James Puter and several others left Santa Fe on a trapping expedition that led into Arizona and California. -

Tours & Treks Summit

2019 Tours & Treks Summit Meet the Team Michael Vincent – Tour Director Alaine Hope – Assistant Tour Coordinator Kelsey Voskamp – Reservations Coordinator Kevin Snow – Historian & Primary Expert Tour Guide Meet the Team Dr. Tom Noel – State Historian Chair & Expert Tour Guide Dr. Andrew Gulliford– Expert Tour Guide History Colorado Volunteers – Judy, Jean, Ellen and Barb. Membership ↘ Membership is here tonight or available via phone at 303-866-3639 ↘ Chat with them if you need to renew or become a member of History Colorado ↘ They can answer any questions about your membership ↘ Only History Colorado members can register for Tours & Treks before January 2019 From the Monte Vista Crane Festival to hikes with state archaeologists, Tours and Treks is supported by you. History Colorado members and donors fund hundreds of hours of historical research and the expertise of educational tour planners -- all of the essential behind- the-scenes work that isn't covered by the price tag of attending a tour. Thank you to our members and donors for making it possible for us to offer these unique experiences to our community. Thank You! Barbara Sweeney – 40 days Janene Bertoncelj – 39 days Cynthia Schuele – 39 days New Booklet Design! Released early January Includes itineraries! Tour or Trek? Tours are two- to six-hour jaunts and include walking and bus tours Treks are usually overnight trips, or they visit areas more than 50 miles from Denver Annual Registration Fee ↘ New in 2019 will be a reduced, one-time, non- refundable, annual registration fee of $5 that goes towards the processing and handling of all History Colorado reservations in the Tours & Treks program. -

National Heritage Areas Congress Has Designated 55 National Heritage Areas (Nhas) to Recognize the Unique National Significance of a Region’S Sites and History

^ NATIONAL PARK SERVICE National Heritage Areas Congress has designated 55 National Heritage Areas (NHAs) to recognize the unique national significance of a region’s sites and history. Through local and regional partnerships with the National Park Service (NPS), these large lived-in landscapes connect heritage conservation with recreation and economic development. NHAs may be managed A site of the Journey Through Hallowed Ground National Heritage by federal commissions, nonprofit groups, Area, Harper’s Ferry National Historical Park in West Virginia tells a diverse, multi-layered history. Some of the stories the universities, and state agencies or municipal park interprets includes John Brown’s attack on slavery, Harriet authorities, guided by a management plan Tubman’s heroic efforts on Underground Railroad, the arrival of the first successful American railroad, the largest surrender of approved by the Secretary of the Interior. Through Federal troops during the Civil War, and the education of former slaves in one of the earliest integrated schools in the United this partnership strategy, heritage areas combine States. historic preservation, cultural and natural resource PHOTO BY FRANK KEHREN conservation, local and regional preservation planning, and heritage education and tourism. FY 2022 Appropriations Request Background National Heritage Areas are Please support $32 million for National Heritage Areas in the FY partnerships among the National 2022 Interior Appropriations bill. Park Service, states, and local communities, in which the NPS APPROPRIATIONS BILL: Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies supports state and local conservation AGENCY: National Park Service through federal recognition, seed ACCOUNT: National Recreation and Preservation money, and technical assistance. ACTIVITY: Heritage Partnership Programs/National Heritage Areas NHAs are designated by individual legislation with specific provisions Recent Funding History: for operation unique to the area’s FY 2019 Enacted Funding: $20.321 million specific resources and desired goals. -

2016 PEIR, Draft December 2015

3.5 CULTURAL RESOURCES This section of the Program Environmental Impact Report (PEIR) describes cultural resources in the SCAG region, discusses the potential impacts of the proposed 2016 Regional Transportation Plan/Sustainable Communities Strategy (“2016 RTP/SCS,” “Plan,” or “Project”) on cultural resources, identifies mitigation measures for the impacts, and evaluates the residual impacts. Cultural resources were evaluated in accordance with Appendix G of the 2015 State California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) Guidelines. Cultural resources within the SCAG region were evaluated at a programmatic level of detail, in relation to the general plans of the six counties and 191 cities within the SCAG region; review of general information characterizing the paleontological resources that have been reported from the SCAG region and review of Dibblee maps of geology and soils; general information characterizing prehistoric and historic human occupation within the SCAG region; general sensitivity of the SCAG region with respect to Native American Sacred sites and tribal cultural resources available through coordination with the Native American Heritage Commission (NAHC) and direct outreach to tribal governments within the SCAG region, including two Native American consultation workshops hosted by SCAG during preparation of the 2016 RTP/SCS and related PEIR; and review of known cemeteries in the SCAG region; a review of related literature germane to the SCAG region; as well as a review of SCAG’s 2012 RTP/SCS PEIR.1 Cultural resources within the SCAG region are recorded in the paleontological fossils; archeological sites and artifacts, historic sites, artifacts, structures and buildings; and the built environment. There is a rich record of archived fossils that are estimated to represent over 500 million years.2 The archaeological record provides evidence of over thousands of years of human occupation. -

Post-Apocalyptic Naming in Cormac Mccarthy's the Road

“Maps of the World in Its Becoming”: Post-Apocalyptic Naming in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road Ashley Kunsa West Virginia University In The Road(2006), Cormac McCarthy’s approach to “naming differently” establishes the imaginative conditions for a New Earth, a New Eden. The novel diverges from the rest of McCarthy’s oeuvre, a change especially evident when the book is set against Blood Meridian because their styles and concomitant worldviews differ so strikingly. The style of The Road is pared down, elemental: it triumphs over the dead and ghostly echoes of the abyss and, alternately, over relentless ironic gesturing. And it is precisely in The Road’s language that we discover the seeds of the work’s unexpectedly optimistic worldview. The novel is best understood as a linguistic journey toward redemption, a search for meaning and pattern in a seemingly meaningless world — a search that, astonishingly, succeeds. Further, I posit The Road as an argument for a new kind of fiction, one that survives after the current paradigm of excess collapses, one that returns to the essential elements of narrative. Keywords: apocalypse / Cormac McCarthy / New Earth / The Road / style ormac McCarthy’s Pulitzer Prize–winning tenth novel The Road (2006) gives us a vision of after: after the world has come to disaster, after any tan- Cgible social order has been destroyed by fire or hunger or despair. McCarthy here surrenders his mythologizing of the past, envisioning instead a post-apoca- lyptic future in which human existence has been reduced to the basics.1 Though the book remains silent on the exact nature of the disaster that befell the planet some ten years prior, the grim results are clear. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history.