History of Minstrelsy, Its Inner Workings and Business

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Spring Newsletter May 2011

Volume 34 Spring Newsletter May 2011 Seldom-Heard Civil then, in September 1861, Elliot was commissioned an officer in the 30th Massachusetts at Camp Chase, Lowell War Tales under the command of General Benjamin F. Butler. Elliott's regiment was among those sent to Ship Island in by Martha Mayo the Gulf of Mexico to begin operations against New Orleans. His diary covers the year of 1862 while in New Come one, come all to a discussion of unusual and seldom Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Vicksburg with detailed heard stories of the Civil War. Our panel will consist of descriptions of his assignments and camp life. A gifted Jack Herlihy, Museum Specialist at the Lowell National artist, the diary features many unique hand-drawn Historical Park; Martha Mayo, librarian and archivist for illustrations of his time on Ship Island and Baton Rouge. LHS; and Attorney Richard P. Howe Jr., Middlesex North Register of Deeds and former Society president. See Calendar of Events on page 6 for location details. A few of the stories to be told include: jjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjjj George J. Fox (1841-1863) – At first Fox was held back from enlisting by his mother, who feared for the safety of her only son. But his belief "that my fathers would be ashamed of me if they were living for not going Part Time Job Opportunity before" compelled Fox to join his cousin David Goodhue Site Coordinator for the Lowell Historical Society. as volunteer in Company C, Massachusetts Sixth ($10/hour, six hour/week with flexible work hours.) Regiment, enlisting for nine months service. -

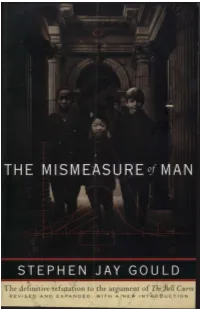

THE MISMEASURE of MAN Revised and Expanded

BY STEPHEN JAY GOULD IN NORTON PAPERBACK EVER SINCE DARWIN Reflections in Natural History THE PANDA'S THUMB More Reflections in Natural History THE MISMEASURE OF MAN Revised and Expanded HEN'S TEETH AND HORSE'S TOES Further Reflections in Natural History THE FLAMINGO'S SMILE Reflections in Natural History AN URCHIN IN THE STORM Essays about Books and Ideas ILLUMINATIONS A Bestiary (with R. W. Purcell) WONDERFUL LIFE The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History BULLY FOR BRONTOSAURUS Reflections in Natural History FINDERS, KEEPERS Treasures amd Oddities of Natural History Collectors from Peter the Great to Louis Agassiz (with R. W. Purcell) THE MISMEASURE OF MAN To the memory of Grammy and Papa Joe, who came, struggled, and prospered, Mr. Goddard notwithstanding. Contents Acknowledgments 15 Introduction to the Revised and Expanded Edition: Thoughts at Age Fifteen 19 The frame of The Mismeasure of Man, 19 Why revise The Mismeasure of Man after fifteen years?, 26 Reasons, history and revision of The Mismeasure of Man, 36 2. American Polygeny and Craniometry before Darwin: Blacks andlndians as Separate, Inferior Species Cfolj 62 A shared context of culture, 63 Preevolutionary styles of scientific racism: monogenism and polygenism, 71 Louis Agassiz—America's theorist of polygeny, 74 Samuel George Morton—empiricist of polygeny, 82 The case of Indian inferiority: Crania Americana The case of the Egyptian catacombs: Crania Aegyptiaca The case of the shifting black mean The final tabulation of 1849 IO CONTENTS Conclusions The American school and -

American Minstrel Show Collection, 1823-1947

AMERICAN MINSTREL SHOW COLLECTION, 1823-1947 Harvard Theatre Collection, Houghton Library, Harvard College Library (USA) Located in the Houghton Library at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, the American Minstrel Show Collection comprises 23 boxes of images of minstrel performers and troupes, playbills and programs of performances, and other miscellaneous materials concerning minstrel shows. A number of performers, troupes and associated practitioners within the collection had either a direct association with Australasia or were indirectly affiliated with the region's minstrel industry. The collection is organised into the following series: I. Images of American minstrel performers and troupes A. Minstrel images, A-Z B. Composite images of minstrels C. Unidentified images of minstrel troupes and individuals II. American minstrel show playbills, A-Z III. Other materials concerning American minstrel shows The images are of individual minstrel performers and troupes, primarily from American minstrel shows ca. 1830s to 1890s. A variety of formats are included: lithographs, photographs, a few etchings and cabinet photographs, printed clippings, photomechanical prints, 1 tintype, and others. Some prints are hand- colored and images depict performers both in character (in "blackface"), as well as in street clothes. For the most part, sheet music in this series is not complete, but are only covers that were collected for the images of the performers. This series also includes other materials such as photomechanical copies of playbills and Charlie Backus broadsides, clippings with images and biographical text, some complete sheet Toured Australia 1855-1856, music, programs, manuscripts, and drawings. 1859-1860 The playbill series includes "true" playbills (long sheets, printed on only one side), printed advertisements, programs (printed on both sides), and programs with sheet music. -

John Mccullough As Man, Actor and Spirit

John McCullough AS Man, Actor and Spirit BY SUSIE C. CLARK Author of "A Look Upward," "Pilate's Query," etc. " Thou art " mighty yet! Thy spirit walks abroad." Julius C&sar WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BOSTON MURRAY AND EMERY COMPANY 1905 VIRGINIUS FA/ . Copyright in 1905 by SUSIE C. CLARK. All rights reserved. INSCRIBED WITH REVERENT LOVE TO THE FA.DELESS MEMORY OF Cental 3nlftt CONTENTS. Chapter I. Introductory 9 II. The Dawn 15 III. The New World 23 IV. The Open Door 29 V. The Golden Gate 39 VI. The Golden Gate (Continued) 53 VII. In Other Fields 61 VIII. McCullough in Boston ' 75 IX. In the Metropolis 92 X. In the Metropolis (Continued) 104 XI. His Greatest Role Ill XII. His Wide Travels 124 XIII. Four Notable Banquets 136 XIV. A Sketch from His Pen 153 XV. Twilight 167 XVI. Sunrise 182 XVII. Impressive Obsequies 200 XVIII. Further Tributes 221 XIX. Final Honors 229 XX. Beyond the Bar 249 XXI. The Next Act in Life's Drama 259 XXII. His Public Work 269 XXIII. Class Work 286 XXIV. As Message Bearer 302 XXV. Reminiscences 310 XXVI. Spiritual Reveries 323 XXVII. Personal 334 XXVIII. The Voice of the Stars. 345 ILLUSTRATIONS. Virginius Frontispiece Coriolanus 82 Spartacus 174 McCullough Memorial 232 Virginius 266 JOHN McCuLLoucH AS MAN, ACTOR AND SPIRIT CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTORY. The harp that once thro' Tara's halls The soul of music shed Now hangs as mute on Tara's walls As if that soul were fled. So sleeps the pride of former days, So glory's thrill is o'er, And hearts that once beat high for praise Now feel that pulse no more." Thomas Moore, Fair Emerald Isle! In verdure clad, thy banks and hills still cheer the eyes of "weary, homesick men far out at sea." Fain would they, as Columbus did of yore, on a Western shore, kneel and kiss thy fair, green sod, which affords the first welcome glimpse of land. -

1 Word Count (Inc. Footnotes): 7,157 Music to Some Consequence

Word count (inc. footnotes): 7,157 Music to some Consequence: Reaction, Reform, Race Philosophers have often been at a loss to explain the secret of the strange power which patriotic tunes seem to exercise over the people . but the mystery is at an end if we are willing to attribute to music the power which I have claimed for it, of pitching high the plane of the emotions, and driving them home with the most efficacious and incomparable energy.1 When the cleric and musical theorist Hugh Reginald Haweis, writing in the 1870s, sought to epitomise his belief in the emotional power of music, he turned to the sphere of national politics. Eighty years earlier, loyalists reacting to the French Revolution turned just as naturally to music: in a much-quoted letter to the activist John Reeves, “A friend to Church and State” maintained that “[A]ny thing written in voice & especially to an Old English tune . made a more fixed Impression on the Minds of the Younger and Lower Class of People, than any written in Prose.”2 Across eight intervening decades these opinions were repeatedly put into practice, as political actors sought to use music “as a powerful secondary agent to deepen and intensify the emotion already awakened by the words of [their creed].”3 Music’s potency was understood to inhere in its ability to arouse and amplify the passions – and though the underlying medical theories shifted over the century, the idea remained: music had a power to mobilise, energise, even effect action by engaging the body and spirit as well as the mind. -

Play-Guide Sunshine-Boys-FNL.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS ABOUT ATC 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE PLAY 2 SYNOPSIS 2 MEET THE CREATOR 2 MEET THE CHARACTERS 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAY 4 COMMENTS ON THE PLAYWRIGHT 6 THE HISTORY OF VAUDEVILLE 7 FamOUS VAUDEVILLIANS 9 A VAUDEVILLE EXCERPT: WEBER AND FIELDS 11 MEDIA TRANSITIONS: THE END OF AN ERA 12 REFERENCES IN THE PLAY 13 DISCUSSION QUESTIONS AND ACTIVITIES 19 The Sunshine Boys Play Guide written and compiled by Katherine Monberg, ATC Literary Assistant. Discussion questions and activities provided by April Jackson, Education Manager, Amber Tibbitts and Bryanna Patrick, Education Associates Support for ATC’s education and community programming has been provided by: APS John and Helen Murphy Foundation The Maurice and Meta Gross Arizona Commission on the Arts National Endowment for the Arts Foundation Bank of America Foundation Phoenix Office of Arts and Culture The Max and Victoria Dreyfus Foundation Blue Cross Blue Shield Arizona PICOR Charitable Foundation The Stocker Foundation City of Glendale Rosemont Copper The William l and Ruth T. Pendleton Community Foundation for Southern Arizona Stonewall Foundation Memorial Fund Cox Charities Target Tucson Medical Center Downtown Tucson Partnership The Boeing Company Tucson Pima Arts Council Enterprise Holdings Foundation The Donald Pitt Family Foundation Wells Fargo Ford Motor Company Fund The Johnson Family Foundation, Inc Freeport-McMoRan Copper & Gold Foundation The Lovell Foundation JPMorgan Chase The Marshall Foundation ABOUT ATC Arizona Theatre Company is a professional, not-for-profit -

Old Time Banjo

|--Compilations | |--Banjer Days | | |--01 Rippling Waters | | |--02 Johnny Don't Get Drunk | | |--03 Hand Me down My Old Suitcase | | |--04 Moonshiner | | |--05 Pass Around the Bottle | | |--06 Florida Blues | | |--07 Cuckoo | | |--08 Dixie Darling | | |--09 I Need a Prayer of Those I Love | | |--10 Waiting for the Robert E Lee | | |--11 Dead March | | |--12 Shady Grove | | |--13 Stay Out of Town | | |--14 I've Been Here a Long Long Time | | |--15 Rolling in My Sweet Baby's Arms | | |--16 Walking in the Parlour | | |--17 Rye Whiskey | | |--18 Little Stream of Whiskey (the dying Hobo) | | |--19 Old Joe Clark | | |--20 Sourwood Mountain | | |--21 Bonnie Blue Eyes | | |--22 Bonnie Prince Charlie | | |--23 Snake Chapman's Tune | | |--24 Rock Andy | | |--25 I'll go Home to My Honey | | `--banjer days | |--Banjo Babes | | |--Banjo Babes 1 | | | |--01 Little Orchid | | | |--02 When I Go To West Virginia | | | |--03 Precious Days | | | |--04 Georgia Buck | | | |--05 Boatman | | | |--06 Rappin Shady Grove | | | |--07 See That My Grave Is Kept Clean | | | |--08 Willie Moore | | | |--09 Greasy Coat | | | |--10 I Love My Honey | | | |--11 High On A Mountain | | | |--12 Maggie May | | | `--13 Banjo Jokes Over Pickin Chicken | | |--Banjo Babes 2 | | | |--01 Hammer Down Girlfriend | | | |--02 Goin' 'Round This World | | | |--03 Down to the Door:Lost Girl | | | |--04 Time to Swim | | | |--05 Chilly Winds | | | |--06 My Drug | | | |--07 Ill Get It Myself | | | |--08 Birdie on the Wire | | | |--09 Trouble on My Mind | | | |--10 Memories of Rain | | | |--12 -

Wisconsin Circus Woes and the Great Dan Rice

200318_EP 5/20/05 10:57 AM Page 18 W ISCONSIN M AGAZINE OF H ISTORY Missouri Historical Society Courtesy of the author In this daguerreotype portrait taken in 1848, Rice’s eyes reveal intelligence and a penchant for mischief; both were crucial to creating clever commentaries As this February on current events. 1860 courier for Wisconsin Circus Woes Dan Rice’s Great Show attests, his audiences got the and the Great Dan Rice usual circus fare of “Educated Mules,” “Anecdote Song and By David Carlyon Story,” and an “Unequaled Troupe,” as well as ircus is regularly told in tales of sweetness and light, and Wisconsin’s cele- a grand spectacle, brated past fills that sentimental bill. In the 1870s, Dan Castello and William “The Magic Ring.” CC. Coup started a show in Racine before heading east to call on P. T. Bar- num, not yet a circus man, to ask for the use of his name to create Barnum & Bailey. Glory—and stories—followed. In the 1880s, the Ringling brothers emerged from Baraboo, and storied glory followed them too. Of course, not all is glorious. Fred Dahlinger Jr. and Stuart Thayer’s Badger State Showmen gives a taste of the tribula- tions that attend circuses, as does Milton J. Bates’s article, “The Wintermutes’ Gigan- tic Little Circus,” which appeared in the Autumn 2003 issue of this magazine. Trouble 18 S UMMER 2005 200318_EP 5/12/05 8:45 PM Page 19 W ISCONSIN M AGAZINE OF H ISTORY hit especially hard in the nineteenth century. Self-anointed Taylor—circuses didn’t have “band chariots” in 1848—nor arbiters of morality condemned the circus, accidents on the lot did “on the bandwagon” start with him. -

Sweets for Sweets

Sweets for SWEETHEARTS Winter wonderland | Radiating heat | Discovering your craft February 2015 foxcitiesmagazine.com Celebrating the Place We Call Home. foxcitiesmagazine.com Publishers Marvin Murphy Ruth Ann Heeter Managing Editor Ruth Ann Heeter [email protected] Associate Editor Amy Hanson [email protected] Editorial Interns Jessica Morgan Mia Sato Reid Trier Haley Walters Art Director Jill Ziesemer Graphic Designer Julia Schnese Account Executives Courtney Martin [email protected] Maria Stevens [email protected] Administrative Assistant/Distribution Nancy D’Agostino [email protected] Printed at Spectra Print Corporation Stevens Point, WI FOX CITIES Magazine is published 11 times annually and is available for the subscription rate of $18 for one year. Subscriptions include our annual Worth the Drive publication, delivered in July. For more information or to learn about advertising opportunities, call (920) 733-7788. © 2015 FOX CITIES Magazine. Unauthorized duplication of any or all content of this publication is prohibited and may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the publisher. FOX CITIES Magazine P.O. Box 2496 Appleton, WI 54912 Facebook.com/foxcitiesmagazine Please pass along or recycle this magazine. February 2015 CONTENTS Features COVER STORY ARTS & CULTURE 14 Winter wonderland Recreation clubs make the most of the cold By Amy Hanson AT HOME 18 Radiating heat Flooring options fend off winter’s freeze 22 By Amy Hanson WEDDINGS: Sweets for sweethearts FOOD & DINING Candy bars bring confections to wedding receptions By Amy Hanson 26 Discovering your craft Local breweries offer handcrafted, flavorful options foxcitiesmagazine.com By Reid Trier Take a look at our new look Are you a fan of FOX CITIES Magazine? Well, now you can get even more of the arts, Departments culture and dining content that you look forward to each month on our brand-new website. -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, som e thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of com puter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMI EDWTN BOOTH .\ND THE THEATRE OF REDEMPTION: AN EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF JOHN WTLKES BOOTH'S ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHANI LINCOLN ON EDWIN BOOTH'S ACTING STYLE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Michael L. -

Polish American and Additional Entry Offices

POLONIA CONGRATULATES POLISH PRESIDENTPOLISH IN NEW AMERICAN YORK — JOURNAL PAGE 3 • NOVEMBER 2015 www.polamjournal.com 1 PERIODICAL POSTAGE PAID AT BOSTON, NEW YORK NEW BOSTON, AT PAID PERIODICAL POSTAGE POLISH AMERICAN OFFICES AND ADDITIONAL ENTRY DEDICATED TO THE PROMOTION AND CONTINUANCE OF POLISH AMERICAN CULTURE JOURNAL REMEMBERING PULASKI AND “THE BIG BURN” ESTABLISHED 1911 NOVEMBER 2015 • VOL. 104, NO. 11 | $2.00 www.polamjournal.com PAGE 16 POLAND MAY SUE AUTHOR GROSS •PASB TILE CAMPAIGN UNVEILING•“JEDLINIOK” TOURS THE EASTERN UNITED STATES HEPI FĘKSGIWYŃG! • A LOOK AT POLAND’S LUTHERANS • FR. MAKA ENLISTS IN NAVY • NOVEMBER HOLIDAYS DO WIDZENIA OR WITAMY AMERIKA? • FATHER LEN’S POLISH CHRISTMAS LEGACY • WIGILIA FAVORITES MADE EASY Newsmark Makes First US Visit Fired Investigator Says US SUPPLY BASES IN POLAND. Warsaw and Washing- House Probe Is Partisan ton have reached agreement on the location of fi ve U.S. WASHINGTON — A The move military supply bases in Poland. The will be established former investigator for the d e - e m - in and around existing Polish military bases Łask, Draws- House Select Committee on phasized ko Pomorskie, Skwierzyna, Ciechanów and Choszczno. PHOTO: RADIO POLSKA Benghazi says he was unlaw- o t h e r Tanks, armored combat vehicles and other military equip- fully fi red in part because he agencies ment will form part of NATO’s quick-reaction spearhead. sought to conduct a compre- involved Siting the storage bases in Poland is expected to facilitate hensive probe into the deadly with the swift mobilization in the event of an attack. The project attacks on the U.S.