Addressing Challenges in Access to Oncology Medicines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Recurrent Mutational Events in Anorectal Melanoma

Modern Pathology (2017) 30, 286–296 286 © 2017 USCAP, Inc All rights reserved 0893-3952/17 $32.00 Identification of recurrent mutational events in anorectal melanoma Hui Min Yang1,2,6, Susan J Hsiao1,6, David F Schaeffer2, Chi Lai3, Helen E Remotti1, David Horst4, Mahesh M Mansukhani1 and Basil A Horst1,5 1Department of Pathology & Cell Biology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA; 2Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada; 3Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, ON, Canada; 4Pathologisches Institut, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universitaet, Muenchen, Germany and 5Department of Dermatology, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY, USA Anorectal melanoma is a rare disease that carries a poor prognosis. To date, limited genetic analyses confirmed KIT mutations as a recurrent genetic event similar to other mucosal melanomas, occurring in up to 30% of anorectal melanomas. Importantly, a subset of tumors harboring activating KIT mutations have been found to respond to c-Kit inhibitor-based therapy, with improved patient survival at advanced tumor stages. We performed comprehensive targeted exon sequencing analysis of 467 cancer-related genes in a larger series of 15 anorectal melanomas, focusing on potentially actionable variants based on gain- and loss-of-function mutations. We report the identification of oncogenic driver events in the majority (93%) of anorectal melanomas. These included variants in canonical MAPK pathway effectors rarely observed in cutaneous melanomas (including an HRAS mutation, as well as a BRAF mutation resulting in duplication of threonine 599), and recurrent mutations in the tumor suppressor NF1 in 20% of cases, which represented the second-most frequently mutated gene after KIT in our series. -

A Phase I Trial of Tamoxifen with Ribociclib (LEE011) in Adult Patients with Advanced ER+ (HER2 Negative) Breast Cancer

The TEEL Study: A Phase I Trial of Tamoxifen with Ribociclib (LEE011) in Adult Patients with Advanced ER+ (HER2 Negative) Breast Cancer NCT02586675 Version 12.0 September 14, 2016 TEEL Protocol- Tamoxifen +Ribociclib Page 1 TITLE PAGE The TEEL Study: A Phase I trial of Tamoxifen with Ribociclib (LEE011) in adult patients with advanced ER+ (HER2 negative) breast cancer. Protocol: MCC 18332 Chesapeake IRB Pro00015228 Principal Investigator: Co-Investigators: Statistician: Experimental Therapeutics Program H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center 12902 Magnolia Drive Tampa, FL 33612 & Comprehensive Breast Program Moffitt McKinley Outpatient Center 10920 N. McKinley Dr. Tampa, FL 33612 Study Site Contact: Protocol Version 12 Date: September 14, 2016 TEEL Protocol- Tamoxifen +Ribociclib Page 2 TITLE PAGE .............................................................................................................................................. 1 SYNOPSIS ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Patient Population ................................................................................................................................. 5 Type of Study ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Prior Therapy......................................................................................................................................... 5 -

Lenograstim in the Treatment of Severe Neutropenia in Patients Treated with Peg-IFN and Ribavirin

Le Infezioni in Medicina, n. 1, 21-23, 2009 Lavori originali Lenograstim in the treatment of severe neutropenia in Original articles patients treated with Peg-IFN and ribavirin: the experience of a single hepatology unit Trattamento mediante lenograstim della neutropenia grave in corso di terapia con Peg-IFN e ribavirina: esperienza di una singola unità di epatologia Luciano Tarantino1, Annunziata De Rosa2, Orsola Tambaro1, Carmine Ripa1, Marta Celiento3, Antonio Schiano1 1Unità di Epatologia ed Ecointerventistica, Ospedale San Giovanni di Dio, Frattamaggiore, Napoli, Italy; 2AOU “Federico II”, Dipartimento di Malattie Infettive, ASL NA 2, Napoli, Italy; 3AOU “Federico II”, Dipartimento di Chirurgia Generale e Geriatria, ASL NA 2, Napoli, Italy n INTRODUCTION doses of 80 mcg s.c./week of Peg-IFN 2b and 1200 mg/die of ribavirin. We checked quanti- he standard treatment of chronic hepatitis C tative HCV- RNA at 12 and 48 weeks of treat- (ECA C) is pegylated interferon-alpha (Peg- ment. Every two weeks, two days before ad- TIFN ) combined with ribavirin [1]. One of the ministration of the weekly dose of Peg-IFN 2b most frequent causes of suspension of therapy or all patients had blood count and liver enzyme reduction of the doses of Peg-IFN is haemato- tests. Patients with absolute neutrophil counts toxicity, which includes anaemia and/or neu- <900 cells/mmc started on lenograstim (263 tropenia and/or thrombocytopenia [2]. The use µg) 24 hours before administration of Peg- of growth factors (G-CSF) in responder patients IFNα 2b (Figure 1). Indication for administer- allows effective doses of Peg-IFN and RIBA to be ing lenograstim was early viral response kept stable [3]. -

Medical Oncology and Breast Cancer

The Breast Center Smilow Cancer Hospital 20 York Street, North Pavilion New Haven, CT 06510 Phone: (203) 200-2328 Fax: (203) 200-2075 MEDICAL ONCOLOGY Treatment for breast cancer is multidisciplinary. The primary physicians with whom you may meet as part of your care are the medical oncologist, the breast surgeon, and often the radiation oncologist. A list of these specialty physicians will be provided to you. Each provider works with a team of caregivers to ensure that every patient receives high quality, personalized, breast cancer care. The medical oncologist specializes in “systemic therapy”, or medications that treat the whole body. For women with early stage breast cancer, systemic therapy is often recommended to provide the best opportunity to prevent breast cancer from returning. SYSTEMIC THERAPY Depending on the specific characteristics of your cancer, your medical oncologist may prescribe systemic therapy. Systemic therapy can be hormone pills, IV chemotherapy, antibody therapy (also called “immunotherapy”), and oral chemotherapy; sometimes patients receive more than one type of systemic therapy. Systemic therapy can happen before surgery (called “neoadjuvant therapy”) or after surgery (“adjuvant therapy”). If appropriate, your breast surgeon and medical oncologist will discuss the benefits of neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy with you. As a National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Member Institution, we are dedicated to following the treatment guidelines that have been shown to be most effective. We also have a variety of clinical trials that will help us find better ways to treat breast cancer. Your medical oncologist will recommend what treatment types and regimens are best for you. The information used to make these decisions include: the location of the cancer, the size of the cancer, the type of cancer, whether the cancer is invasive, the grade of the cancer (a measure of its aggressiveness), prognostic factors such as hormone receptors and HER2 status, and lymph node involvement. -

PD-1/PD-L1 Targeting in Breast Cancer: the First Clinical Evidences Are Emerging

Supplementary Materials: PD-1/PD-L1 Targeting in Breast Cancer: the First Clinical Evidences are Emerging. A Literature Review Table S1. Interventional studies with anti PD-1 or PDL-1 agents recruiting. Non-intraveinous administrations are indicated between brackets. Estimated Estimated Study Ph. Anti-PD(L)-1 Single (S) or Combination Study title NCT Conditions or disease Enrollement Sponsor Completion Date (n=) Inflammatory and metastatic breast cancer (IBC) 1 Pembrolizumab S MK-3475 for Metastatic Inflammatory Breast Cancer (MIBC) 02411656 35 June 2020 MD Anderson or mTNBC Entinostat, Nivolumab, and Ipilimumab in treating patients Breast carcinoma: HER2 negative, Ipilimumab with solid tumors that are metastatic or cannot be removed by Invasive BC, Metastatic BC 1 Entinostat [PO] 02453620 45 December 2019 NCI Nivolumab surgery or locally advanced or metastatic HER2-NegativeBreast BC stage III, IIIA, IIIB, IIIC, IV Cancer Unresectable solid neoplasm Adjuvant PVX-410 Vaccine and Durvalumab in stage II/III TNBC stage II, III; HLA-A2 positive by Massachusetts 1 Durvalumab PVX-410 [IM] 02826434 20 December 2022 Triple Negative Breast Cancer deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) sequence analysis General Hospit A Study of changes in PD-L1 expression during preoperative Pembrolizumab 1 Nab-paclitaxel treatment with Nab-Paclitaxel and pembrolizumab in Hormone 02999477 HR positive breast cancer 50 January 2023 Dana-Farber Receptor (HR) Positive BC Cisplatine PD1 Antibody + GP as first line treatment for triple negative Fudan 1 JS001 (anti PD1) Gemcitabine -

PRIOR AUTHORIZATION CRITERIA for APPROVAL Initial Evaluation Target Agent(S) Will Be Approved When ONE of the Following Is Met: 1

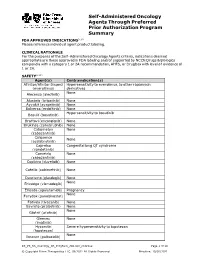

Self-Administered Oncology Agents Through Preferred Prior Authorization Program Summary FDA APPROVED INDICATIONS3-104 Please reference individual agent product labeling. CLINICAL RATIONALE For the purposes of the Self -Administered Oncology Agents criteria, indications deemed appropriate are those approved in FDA labeling and/or supported by NCCN Drugs & Biologics compendia with a category 1 or 2A recommendation, AHFS, or DrugDex with level of evidence of 1 or 2A. SAFETY3-104 Agent(s) Contraindication(s) Afinitor/Afinitor Disperz Hypersensitivity to everolimus, to other rapamycin (everolimus) derivatives None Alecensa (alectinib) Alunbrig (brigatinib) None Ayvakit (avapritinib) None Balversa (erdafitinib) None Hypersensitivity to bosutinib Bosulif (bosutinib) Braftovi (encorafenib) None Brukinsa (zanubrutinib) None Cabometyx None (cabozantinib) Calquence None (acalabrutinib) Caprelsa Congenital long QT syndrome (vandetanib) Cometriq None (cabozantinib) Copiktra (duvelisib) None Cotellic (cobimetinib) None Daurismo (glasdegib) None None Erivedge (vismodegib) Erleada (apalutamide) Pregnancy None Farydak (panobinostat) Fotivda (tivozanib) None Gavreto (pralsetinib) None None Gilotrif (afatinib) Gleevec None (imatinib) Hycamtin Severe hypersensitivity to topotecan (topotecan) None Ibrance (palbociclib) KS_PS_SA_Oncology_PA_ProgSum_AR1020_r0821v2 Page 1 of 19 © Copyright Prime Therapeutics LLC. 08/2021 All Rights Reserved Effective: 10/01/2021 Agent(s) Contraindication(s) None Iclusig (ponatinib) Idhifa (enasidenib) None Imbruvica (ibrutinib) -

Infection Prevention in Outpatient Oncology Settings CDC Offers Tools to Fight Back Against Infections Among Cancer Patients

Infection prevention in outpatient oncology settings CDC offers tools to fight back against infections among cancer patients. By aLICE y. GUh, MD, MPh, LiSa c. RICHARDSOn, MD, MPh, AND ANGeLa DUnBAR, BS espite advances in oncology care, infections remain a major www.preventcancerinfections.org 1-3 cause of morbidity and mortality among cancer patients. 1. What? PREPARE: Watch Out for Fever! You should take your temperature any time you blood cell count is likely to be the lowest since in that you are a cancer patient undergoing When? feel warm, flushed, chilled or not well. If you get a this is when you’re most at risk for infection chemotherapy. If you have a fever, you might temperature of 100.4°F (38°C) or higher for more (also called nadir). have an infection. This is a life threatening Several factors predispose cancer patients to developing infec- than one hour, or a one-time temperature of 101° • Keep a working thermometer in a convenient condition, and you should be seen in a short F or higher, call your doctor immediately, even if location and know how to use it. amount of time. it is the middle of the night. DO NOT wait until the • Keep your doctor’s phone numbers with you at office re-opens before you call. all times. Make sure you know what number to call when their office is open and closed. tions, including immunosuppression from their underlying You should also: • If you have to go to the emergency room, it's • Find out from your doctor when your white important that you tell the person checking you • If you develop a fever during your chemotherapy treatment it is a medical emergency. -

Mutant Cancers 2 3 Heinz Hammerlindl1*, Dinoop Ravindran Menon1*, Sabrina Hammerlindl1, Abdullah Al

Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on December 1, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2118 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Hammerlindl et. al 1 Acetylsalicylic Acid Governs the Effect of Sorafenib in RAS Mutant Cancers 2 3 Heinz Hammerlindl1*, Dinoop Ravindran Menon1*, Sabrina Hammerlindl1, Abdullah Al 4 Emran1, Joachim Torrano1, Katrin Sproesser3, Divya Thakkar1, Min Xiao3, Victoria G. 5 Atkinson5, Brian Gabrielli4, Nikolas K. Haass2, Meenhard Herlyn3, Clemens Krepler3, Helmut 6 Schaider1,2† 7 8 1Dermatology Research Centre, The University of Queensland, The University of 9 Queensland Diamantina Institute, Translational Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia; 10 2The University of Queensland, The University of Queensland Diamantina Institute, 11 Translational Research Institute, Brisbane, Australia; 12 3The Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, PA, U.S.A.; 13 4Mater Medical Research Institute, The University of Queensland, Translational Research 14 Institute, Brisbane, Australia; 15 5Division of Cancer Services, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia; 16 *These authors contributed equally to the study 17 18 Running title: 19 Combined aspirin and sorafenib for RAS-mutant cancer therapy 20 21 Key words: 22 Melanoma, Lung Cancer, NRAS, Sorafenib, Aspirin, RAS, ERK, AMPK 23 24 25 26 27 28 1 Downloaded from clincancerres.aacrjournals.org on September 24, 2021. © 2017 American Association for Cancer Research. Author Manuscript Published OnlineFirst on December 1, 2017; DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2118 Author manuscripts have been peer reviewed and accepted for publication but have not yet been edited. Hammerlindl et. al 1 2 Grant Support 3 This work was funded by the Epiderm Foundation (H.S.), the Princess Alexandra Hospital 4 Research Foundation (PARSS2016_NearMiss) (H.S.), NIH grants PO1 CA114046, P50 5 CA174523, and the Dr. -

Welcome to the Department of Oncology-Pathology

Photo: H. Flank WELCOME TO THE DEPARTMENT OF ONCOLOGY-PATHOLOGY Photo: S. Ceder Photo: Erik Cronberg Photo: H. Flank Photo: E. H. Cheteh & S. Ceder t. Solna JohanOlof Wallins väg Wallins JohanOlof SKALA Solregnsvägen 0255075 100 125 m Solna kyrkväg Solnavägen Prostvägen 1 Prostvägen DEPARTMENT OF Fogdevreten ONCOLOGY-PATHOLOGY Prostvägen Granits väg Science for Life Laboratory We are a part of Karolinska Institutet, where we work with cancer research and offer Solna kyrkväg educational programs at undergraduate, Master and doctoral levels. Uniting more Tomtebodavägen than 30 research groups, the department´s broad focus on cancer combines basic, translational and clinical research, ranging from mechanisms of cancer development and biomarkers to development of new technologies for precision cancer medicine. Spårområde Karolinska vägen Thus, our goals are, based on fundamental discoveries, to identify and implement Nobels väg Tomtebodavägen cancer biomarkers supporting early diagnosis and improved personalized therapy, Widerströmska building and to drive drug discovery via innovative clinical trials. Further, we engage in edu-Tomtebodavägen cation of next generation scientist and healthcare professionals in these areas.P Our research teams are mainly located at two research buildings, Bioclinicum and Science for Life Laboratories (SciLifeLab), Solna, and at hospital buildings including Pathology unit and New Karolinska Hospital (NKS), Stockholm. In addition, few Scheeles väg Theorells väg research groups form satellites in Södersjukhuset, Karolinska hospital in Huddinge 3 and at Cancercentrum Karolinska, Solna. Karolinska vägen Scheeles väg Retzius väg Nobels väg Biomedicum Solnavägen Science for Life laboratories Individual research groups are part of both the department of Oncology-Pathology and Tomtebodavägen the SciLifeLabs national infrastructure. -

Covid Management of Liquid Oncology Patients

CELLICONE VALLEY ‘21: THE FUTURE OF CELL AND GENE THERAPIES COVID MANAGEMENT OF LIQUID ONCOLOGY PATIENTS Abbey Walsh, MSN, RN, OCN – Clinical Practice Lead, Outpatient Infusion Therapy Angela Rubin, BSN, RN, OCN – Clinical Nurse III, Outpatient Infusion Therapy May 6th, 2021 Disclosures: ‣ Both presenters have disclosed no conflicts of interests related to this topic. 2 Objectives: ‣ Describe the evolution of COVID management for oncology patients being treated in ambulatory care. ‣ Identity the role of EUA monoclonal antibody treatments for COVID + oncology patients. ‣ Review COVID clearance strategies: past and present. ‣ Explain Penn Medicine's role in COVID vaccinations for oncology patients. ‣ Explain COVID – 19 special care considerations for oncology patients: • Emergency Management • Neutropenic Fevers/Infectious Work-ups • Nurse-Driven Initiatives • Cancer Center Initiatives to enhance patient safety and infection risk 3 Evolution of COVID Management for Oncology Patients in Ambulatory Care Late March – Early April 2020: COVID Testing Strategies “COLD” Testing “HOT” Testing • Assume these patients are COVID Negative. • Actively COVID + or suspicious for COVID/PUI • No need for escort in and out of the building (Patient under investigation) • Maintain Droplet Precautions: • Require RN/CNA escort in and out of building. • Enhanced PPE for COVID swab only • Enhanced precautions: • Patients who are asymptomatic but require • (Enhanced) Droplet + Contact COVID testing: • Upgrade to N95 during aerosolizing • Pre-admission procedures • Pre-procedural • (PUIs)-COVID testing indicated because of: New Symptoms, Recent Travel, Recent known exposure to Covid + individual • Examples: Port placement, starting radiation treatment, CarT therapy, Stem • Example: Liquid oncology patient arrives Cell/Bone Marrow Transplant patients for chemo treatment, but reports new cough and fevers up to 101 over the last • Exlcusion: pre-treatment outpatient anti- few days. -

Management of Multiple Myeloma: the Changing Paradigm

Management of Multiple Myeloma: The Changing Paradigm Relapsed/Refractory Disease Jeffrey A. Zonder, MD Karmanos Cancer Institute Objectives • Discuss use of standard myeloma therapies when used as therapy after relapse • Consider patient and disease factors which might impact therapy decisions. • Describe off-label options for patients who are not protocol candidates. Line ≠ Line ≠ Line ≠ … POLICE LINE – DO NOT CROSS POLICE LINE – DO NOT CROSS POLICE LINE – DO NOT CROSS POLICE LINE – DO NOT CROSS POLI LINE – DO NOT Define “Line” • A pre-defined course of therapy utilizing agents either simultaneously or sequentially – Len/Dex – Len/Dex ASCT – Vel/Dex ASCT Len/Dex – VDT-PACE ASCT TD ASCT VPT-PACE LD • Pts who have had the same # of “lines” of Rx may have had vastly different amounts of Rx What Is Relapsed/Refractory Disease? • Relapsed: recurrence after a response to therapy • Refractory: progression despite ongoing therapy What Do We Know About the Pt’s Myeloma? • What prior therapy has been used? • How well did it work? • Did the myeloma progress on active therapy? • High-risk cytogenetics/FISH/GEP? What Do We Know About the Patient? • Age • Other medical problems – Diabetes – Blood Clots • Lasting side effects from past therapies – Peripheral Neuropathy • Personal preferences and values Choosing Therapy for Relapsed/Refractory Myeloma Proteasome IMiDs Anthracyclines Alkylators Steroids HDACs Antibodies Inhibitors Thalidomide Bortezomib Doxil Melphalan Dex Panobinostat Elotuzumab Lenalidomide Carfilzomib Cytoxan Pred Vorinostat -

Spotlight on Ixazomib: Potential in the Treatment of Multiple Myeloma Barbara Muz Washington University School of Medicine in St

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2016 Spotlight on ixazomib: Potential in the treatment of multiple myeloma Barbara Muz Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Rachel N. Ghazarian Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Monica Ou Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Micha J. Luderer Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Hubert D. Kusdono Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Muz, Barbara; Ghazarian, Rachel N.; Ou, Monica; Luderer, Micha J.; Kusdono, Hubert D.; and Azab, Abdel K., ,"Spotlight on ixazomib: Potential in the treatment of multiple myeloma." Drug Design, Development and Therapy.2016,10. 217-226. (2016). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/5207 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Barbara Muz, Rachel N. Ghazarian, Monica Ou, Micha J. Luderer, Hubert D. Kusdono, and Abdel K. Azab This open access publication is available at Digital Commons@Becker: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/5207 Journal name: Drug Design, Development and Therapy Article Designation: Review Year: 2016 Volume: