A Report on an Evaluation of Mother Based Early Learning and Parent + (MTELP+) Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Analysis (28 May, 2020)

News Analysis (28 May, 2020) drishtiias.com/current-affairs-news-analysis-editorials/news-analysis/28-05-2020/print USA Offers Mediation Between India and China Why in News Recently, the USA President has offered to mediate between India and China over the Indo- China border standoff. The offer has come in the backdrop of the ongoing standoff between India and China along the Line of Actual Control (LAC). Background Currently, India and China faces standoff at least four points along the LAC, including Pangong Tso lake, Demchok and Galwan Valley in Ladakh and Naku La in Sikkim. The tensions between two countries escalated along the LAC after China ordered the military to scale up battle preparedness and asked it to resolutely defend the country’s sovereignty. Subsequently, India has also increased its presence on the boundary with China in North Sikkim, Uttarakhand, Arunachal Pradesh, along with Ladakh. So far, at least six rounds of talks have been held between Indian and Chinese military commanders in Ladakh on the ground but have failed to achieve a breakthrough. Key Points 1/14 Offer by USA: The USA President has informed both India and China that the United States is willing and able to mediate or arbitrate their raging border dispute. It is the first time that the USA made such an offer to India and China, referring to the LAC situation as a “raging border dispute”. In the past, the USA had offered to mediate between India and Pakistan over Kashmir but it was rejected by India. India had cleared its position stating that the issue can only be discussed bilaterally. -

OFFICE of the TAHASILDAR, RAIKIA KANDHAMAL Memo No L)4\

OFFICE OF THE TAHASILDAR, RAIKIA 'l'cl: o68.17-z647oo KANDHAMAL L.Nu. ....1..+,Y1... Email: tahasildarraikia @g:latLq.tr4 Date 10.()8.2o21 To The Deputy Dircctor, (Advertisement) Cum- Deputy Secretary to Govt. I & P.R. Deptt., Odisha, Bhubaneswar. Sub: - Publication of Advertisement for 5 years lease of Sairat Sources under Raikia Tahasil for the year 2O2l-22 to 2025-26 S ir, ln enclosing herer,"'ith the advertiseeement of Sairat Sources under Raikia Tahasil of Kandhamal District, I am to request you for publication of the same at an early date in one odiya daily news paper paper having circulation in Kandhamal District for 2 consccutive days for wide publicity. The Soft copy of the advertisement is also submitted through on line to the e- mail ID ipr.advt(ri,email.com with copy to iprnews(rlrgmail.com. A copy of the advertisement may kindly be supplied to this oflice for reference. Encl: As above Yours faithfully Tahasilda.r. Rakia . Memo No l)4\ Date 10.08.202 1 V' rrltldr' l11trr] Copy e ong with cop1, o1 enclosers submltted t" th5t'dlq#eoq\tandhamal, Phulbani/ Sub-Collector, Balliguda for information and necessary action. Copy along nith copy of advertisement forwarded to the D.I.O, NIC, Kar-rdhamal, Phulbani for information ald uploading of the same in District Websrte. Copy along with copy of advertisement forwarded to the D.l.P.R.O, Kaldhamal, Phulbani for information arrd co-ordinate the above matter. l, (, , , $!frFjl@*i'nari' ' ^rl ll . ' irli''. oaQa ardq t6'q, olo6al , 6nr- ooctte ASIQQ tr6or nger6e, gov 6etG aroc -2004 ( a'66tqo atae -2016) <ogrer qs{srlrod ac,6r6 6ose eora 6aroraa6 60, 6,$qrn 6nt aegio orra6ar aa'Qn e, rd! taq aqas 8o nq tOa E or aa 96o s edar fr6' q6g 6oc,r 6ose aqo ar6 q,06rg 6eeroe org arqra aerro aa6 I e,ro oC .(er a6,qre aqaE" fra oqora oar e,r6erq or{o6 , eosq, 6firr website: www.kandhamal.nic.in 60 aofiq aee 6qr qflg ordqoeqeer 6q qroerorertq'orcivrmQeer sq 6fr66 sorerreo16r a6oreree t oq'Qnore, eraGar i : :oq":lP ,t., rgs,q8&flgtFBr ,'-n i,t Dt 1At",iA I. -

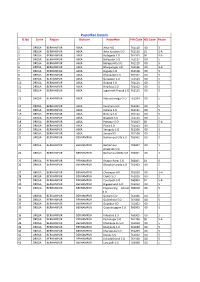

Post Offices of Odisha Circle Covered Under "Core Operation"

Postoffice Details Sl.No Circle Region Division Postoffice PIN Code ND Code Phase 1 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Aska H.O 761110 00 3 2 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Aska Junction S.O 761110 01 5-A 3 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Badagada S.O 761109 00 5-A 4 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Ballipadar S.O 761117 00 5 5 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Bellagunhta S.O 761119 00 5 6 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Bhanjanagar HO 761126 00 3-A 7 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Buguda S.O 761118 00 5 8 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Dharakote S.O 761107 00 5 9 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Gangapur S.O 761123 00 5 10 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Gobara S.O 761124 00 5 11 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Hinjilicut S.O 761102 00 5 12 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Jagannath Prasad S.O 761121 00 5 13 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Kabisuryanagar S.O 761104 00 5 14 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Kanchuru S.O 761101 00 5 15 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Kullada S.O 761131 00 5 16 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Nimina S.O 761122 00 5 17 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Nuagam S.O 761111 00 5 18 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Pattapur S.O 761013 00 5-A 19 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Pitala S.O 761103 00 5 20 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Seragada S.O 761106 00 5 21 ORISSA BERHAMPUR ASKA Sorada SO 761108 00 2 22 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Berhampur City S.O 760002 00 5 23 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Berhampur 760007 00 5 University S.O 24 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Berhampur(GM) H.O 760001 00 3 25 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Bhapur Bazar S.O 760001 03 6 26 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Bhatakumarada S.O 761003 00 5 27 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Chatrapur HO 761020 00 3-A 28 ORISSA BERHAMPUR BERHAMPUR Chikiti S.O 761010 00 5 -

District Statistical Hand Book, Kandhamal, 2018

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA DISTRICT STATISTICAL HAND BOOK KANDHAMAL 2018 DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS AND STATISTICS, ODISHA ARTHANITI ‘O’ PARISANKHYAN BHAWAN HEADS OF DEPARTMENT CAMPUS, BHUBANESWAR PIN-751001 Email : [email protected]/[email protected] Website : desorissa.nic.in [Price : Rs.25.00] ସଙ୍କର୍ଷଣ ସାହୁ, ଭା.ପ.ସସ ଅର୍ଥନୀତି ଓ ପରିସଂ孍ୟାନ ଭବନ ନିର୍ଦ୍ଦେଶକ Arthaniti ‘O’ Parisankhyan Bhawan ଅର୍େନୀତି ଓ ପରିସଂଖ୍ୟାନ HOD Campus, Unit-V Sankarsana Sahoo, ISS Bhubaneswar -751001, Odisha Director Phone : 0674 -2391295 Economics & Statistics e-mail : [email protected] Foreword I am very glad to know that the Publication Division of Directorate of Economics & Statistics (DES) has brought out District Statistical Hand Book-2018. This book contains key statistical data on various socio-economic aspects of the District and will help as a reference book for the Policy Planners, Administrators, Researchers and Academicians. The present issue has been enriched with inclusions like various health programmes, activities of the SHGs, programmes under ICDS and employment generated under MGNREGS in different blocks of the District. I would like to express my thanks to Sri P. M. Dwibedy, Joint Director, DE&S, Bhubaneswar for his valuable inputs and express my thanks to the officers and staff of Publication Division of DES for their efforts in bringing out this publication. I also express my thanks to the Deputy Director (P&S) and his staff of DPMU, Kandhamal for their tireless efforts in compilation of this valuable Hand Book for the District. Bhubaneswar (S. Sahoo) July, 2020 Sri Pabitra Mohan Dwibedy, Joint Director Directorate of Economics & Statistics Odisha, Bhubaneswar Preface The District Statistical Hand Book, Kandhamal’ 2018 is a step forward for evidence based planning with compilation of sub-district level information. -

High Court of Orissa : Cuttack

HIGH COURT OF ORISSA : CUTTACK DIRECT RECRUITMENT FROM THE BAR - 2018 ADVERTISEMENT NO. 1/2018 DATE OF WRITTEN EXAMINATION :- 16.12.2018 (SUNDAY) CENTRE OF EXAMINATION :- CAMBRIDGE SCHOOL, CANTONMENT ROAD, CUTTACK SCHEDULE OF EXAMINATION : 1ST SITTING (PAPER –I) 2ND SITTING (PAPER – II) 10.30 A.M – 12.30 P.M 2.00 P.M – 4.00 P.M. LIST OF ELIGIBLE CANDIDATES ASSIGNED WITH ROLL NOS. TO APPEAR AT THE WRITTEN EXAMINATION Sl. Name of the Father’s Name Permanent Present Address Roll Number No. applicant / Husband’s Address Name 1. SUMITA RAJ Surendra At/Po- Boudh At/Po- Boudh 001 Kumar Raj Town (Poda Town (Poda Pada), PS/Dist - Pada), PS/Dist - Boudh Boudh 2. SRIYAPATI Late Uddhaba At/Po- Bakingia, CDA, Sector - 7, 002 PRADHAN Pradhan PS- Raikia, Dist- Plot No.-E/278, Kandhamal Markat Nagar, Cuttack 3. TAPAN Narasingha At- At- Plot No.- 4c- 003 KUMAR JENA Jena Samanta Athagarhpatna, 1365, Sector - 11, SAMANTA Dist- Ganjam, Dist- Cuttack, Odisha, PIN- Odisha - 753015 761105 4. P. Late P. At- Khosallpur, C/O- Badan 004 PADMAVATI Punnaram PO- Sunguda, Sahoo, At- Alisha Via- Dharmasala, Bazar, PO- Dist- Cuttack Chandini Chowk, PS- Lalbag, Dist- Cuttack, PIN- 753002 1 5. PUSPANJALI W/O- Prasanta At- Atoda, PO- At- Atoda, PO- 005 PANDA Kumar Patpur, PS- Patpur, PS- Panigrahi Jagatpur, Dist- Jagatpur, Dist- Cuttack, PIN- Cuttack, PIN- 754200 754200 6. MD. AMIRUL Abdul Sakur At- Padampur, At- Padampur, 006 HUSSAIN PO/PS- Jashipur, PO/PS- Jashipur, Dist- Mayurbhanj Dist- Mayurbhanj 7. PRASANT Srikant Chhayapath Lane, Chhayapath Lane, 007 PATTANAIK Pattanaik Ratanpur Road, Ratanpur Road, Nayagarh, PIN- Nayagarh, PIN- 752069 752069 8. -

UGC HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT CENTRE SAMBALPUR UNIVERSITY 1. REFRESHER COURSE in CHEMISTRY (From 03.07.2014 to 23.07.2014)

UGC HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT CENTRE SAMBALPUR UNIVERSITY 1. REFRESHER COURSE IN CHEMISTRY (From 03.07.2014 to 23.07.2014) Sl. Name, Designation & College Address of the participants No. 1. RAJESH KUMAR SAHOO Lecturer in Chemistry, B. J. B. Jr. College, Bhubaneswar- 751001 2. BHAGABAT BHUYAN Jr. Lecturer in Chemistry, F. M. Junior College, Balasore- 756001 3. SUJATA SAHU Lecturer in Chemistry, Betnoti College, Betnoti, Mayurbhanj-757025 4. BASANTA KUMAR BHOI Lecturer in Chemistry, Nilamani Mahavidyalaya, Rupsa, Balasore-756028 5. BISHNU CHARAN BEHERA Lecturer in Chemistry, M. G. Mahavidyalaya, Baisinga, Mayurbhanj- 757028 6. DEBA PRASANNA MOHANTY Lecturer in Chemistry, V. N. (Auto) College, Jajpur Road, Jajpur, 755019 7. DR. NILANCHALA PATEL Lecturer in Chemistry, Govt. (Auto) College, Rourkela, Sundargarh 8. RANJAN KUMAR PRADHAN Lecturer in Chemistry, V. Deb. College, Jeypore, Koraput- 764004 9. V. RAMESWAR RAJU Lecturer in Chemistry, Science College, Hinjilicut, Ganjam- 761102 10. SADASIBA MISHRA Lecturer in Chemistry, Panchayat College, Kalla, Deogarh- 768110 11. SADASHIBA NAYAK Lecturer in Chemistry, Saheed Memorial College, Manida, Mayurbhanj- 757020 12. DR. BRUNDABAN NAYAK Lecturer in Chemistry, People’s College, Buguda, Ganjam- 761118 13. DR. RAMAKRISHNA D. S. Lecturer in Chemistry, VSSUT, Burla- 768018 14. ASHOK PADHAN Lecturer in Chemistry, Attabira College, Attabira, Bargarh- 768027 15. DR. ARUNA KUMAR MISRA Lecturer in Chemistry, Rayagada (Auto) College, Rayagada 16. SUMANTA KUMAR PATEL, Lecturer in Chemistry, Kuchinda College, Kuchinda, Sambalpur 17. JYOTIRMAYEE PANIGRAHI Lecturer in Chemistry, Talcher (Auto) College, Talcher, Angul 18. SMITA RANI SAHOO Lecturer in Chemistry, Parjang College, Parjang 19. DR. MANORAMA SENAPATI Lecturer in Chemistry, N.S.B. Mahavidyalaya, Nuvapada, Ganjam 20. -

Sushrita Pattanaik

SUSHRITA PATTANAIK Career Objective : To be a good journalist Educational Qualification : B.A., Hon.- Education, Nachuni Maha- vidyalaya, Nachuni, Utkal University, 2013. Professional Qualification : Master in Journalism and Mass Communica- tion, IMS, Utkal University, 2015 Experiecne : 45 days experience as internship trainee in media sector. Personal Details Father’s Name : Sri Sarat Chandra Pattanaik Date of Birth : 14th Jan. 1993 Sex : Female Present Address : At/Po - Nachuni, Dist. - Khurda Phone (Mobile / Land) : 8342048858 E-mail : [email protected] Religion : Hindu Marital Status : Single Language Known : Odia, English & Hindi Interest & Activities : Reading story books [1] GAYATRI PRADHAN Career Objective : To be a good Journalist. Educational Qualification : B.A., Hon.- Education, Nachuni Mahavidyalaya, Nachuni, Utkal University, 2013. Professional Qualification : Master in Journalism and Mass Communica- tion, IMS, Utkal University, 2015 Experiecne : 45 days experience as internship trainee in media sector. Personal Details Father’s Name : Sri Manguli Pradhan Date of Birth : 1st Jan. 1993 Sex : Female Present Address : At/Po: Pariorad, Via - Tangi, Dist- Khurda, Pin -752023 Phone (Mobile / Land) : 7205778009 E-mail : [email protected] Religion : Hindu Marital Status : Single Language Known : Odia, English & Hindi Interest & Activities : Reading Books [2] RAJ KUMAR MOHANTY Career Objective : To be a good journalist. Educational Qualification : B.Com., G. C. College, Ramachandrapur, Utkal University, 2013. -

ANSWERED ON:10.04.2017 Digital Study Material Patole Shri Nanabhau Falgunrao

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:5771 ANSWERED ON:10.04.2017 Digital Study Material Patole Shri Nanabhau Falgunrao Will the Minister of HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT be pleased to state: (a) the details of mobile apps and websites launched under Digital India initiative by the Government to make the study material available online to students; (b) the details of the scheme named 'Saransh' launched by the Government for the CBSE students; (c) the details of the facilities made available to the parents for the comparative information regarding the performance of students at district, State and National level; and (d) the time-limit set up for the use of technology to bring transparency in school education system and reduce the burden of examinations and the details thereof? Answer MINISTER OF STATE IN THE MINISTRY OF HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT (SHRI UPENDRA KUSHWAHA) (a) The Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD) has created a website, namely, swayam (www.swayam.gov.in) and swayam mobile app for iPhone Operating System (iOS), Android and Windows Platform to make study material available online to students. In addition, the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) has also launched a web portal and a mobile app, namely, e-Pathshala (http://epathshala.nic.in & http://epathshala.gov.in), which provides access to textbooks and other resources developed by the NCERT. The Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) has started e-CBSE website and mobile apps to make the study material of CBSE available online to students. (b) With a vision of "Improving children's education by enhancing interaction between schools as well as parents and providing data driven decision support system to assist them in taking best decisions for their children's future", the CBSE has developed an in- house decision support system called 'SARANSH'. -

Orissa Communal Violence

Date wise incidents of riot… from 19.08.08 to 17.09.08 Date Time Place Subject /incident The threatening letter Reached Chakapada Ashram, 19.0808 Chakapada posted date: 09/08/08. the letter bears to keep off himself from all sorts of violence, and keep peace. 22.08.08 Swami Laxmananada reached in evening at Chakapada ashram. Tumudibanhda Sawamiee Reported at Tumudibadha Police station about the letter and of his security. Around 7 pm armed militants entered to the Jaleshpata Ashram (Shankaracharya Shanskruta 23.08.08 Jalespata ashram Kanyashram), including Swamijee 5 person were killed by bullet. On 8 pm police force reached to the ashram. One hand-written letter was found written by CPI Jalespata Ashram Mauwadi where they have mentioned why they have done it. The vehicle carrying HM sisters near Ainthapally in Sambalpur Sambalpur, a prayer chapel at Tentuliapadar in Sundargarh was also burned and destroyed. Section 144 of ICP is declared in all over Kandhamal 24.08.08 Kandhamal district. High alert in State. CM requested to all to maintain and keep Peace. Kothagoda Sister were on the way of G Udayagiri, towords Berhampur, they were pulled out from the G. Udayagiri vehicle. Vehicle was then set on fire and the driven was severely beaten up. Orissa In different places Road blocked and shops were off in Orissa. One man, a handicapped believer namely Rasananda Pradhan at Rupagaon, was burnt alive. He could not run to the forest when others rushed and saved Rupagaon their lives. As his two legs doesn't function, he could not run and save himself when radicals out of rampage set ablaze that whole village, 25 houses together damaged at midnight. -

Schedule of Tender for External Electrification Work of Sdpo , Rairakhol in the Dist

THE ODISHA STATE POLICE HOUSING & WELFARE CORPORATION LTD. JANPATH, BHUBANESWAR-22. Tel: 0674 2541545; Fax: 0674 2541543; E-mail : [email protected] Web: ophwc.nic.in BID REFERENCE NO: - 04/ 2016-17/ELECT/ OPHWC SCHEDULE OF TENDER FOR EXTERNAL ELECTRIFICATION WORK OF SDPO , RAIRAKHOL IN THE DIST. OF SAMBALPUR. SOLD TO : M/S __________________________________________ __________________________________________ MONEY RECEIPT NO : ___________________________________________ DATE : ___________________________________________ [SIGNATURE OF ISSUING OFFICER] THE ODISHA STATE POLICE HOUSING & WELFARE CORPORATION LTD. JANPATH, BHUBANESWAR-22. Tel: 0674 2541545; Fax: 0674 2541543; E-mail : [email protected] Web: ophwc.nic.in TENDER CALL NOTICE BID REFERENCE NO: - 04/ 2016-17/ELECT/ OPHWC 1. Sealed tender in the prescribed form with detailed Tender Call Notice for execution of External Electrification work of different projects are invited in single cover system from the enlisted H.T. Electrical Contractors/Firms under O.P.H.W.C., Bhubaneswar including supply of materials as per the specification. Tender to be submitted separately for each project. Period Cost of of Sl.No Name of the Project Estimated Cost EMD Eligibility tender paper complet Range including vat ion External Electrification work of Upto 10 New Police Transit lakh & 1 House, Gopalpur in Rs.6,23,222.00 Rs.6,232.00 Rs.4,200.00 90 days above the Dist. of Ganjam.(Pol-2011- 6652) LT Extension to 1-D,2- Upto 10 E & 6-F type Qtr. at lakh & 2 Gadi Fire Station in the Rs.1,35,325.00 Rs.1353.00 Rs.630.00 90 days Dist. of Bhadrak.(CA- above 7943,7943A,7943B) External Electrification Upto 10 work of Office-cum- lakh & 3 residence of SDPO at G. -

Ground Water Year Book 2016-2017

Government of India CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD Ministry of Water Resources & Ganga Rejuvenation GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK 2016-2017 South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar September 2017 F O R E W O R D Groundwater is a major natural replenishable resource to meet the water requirement for irrigation, domestic and industrial needs. It plays a key role in the agrarian economy of the state. Though richly endowed with various natural resources, the state of Orissa has a long way to go before it can call itself developed. Being heavily dependent on rain fed agriculture; the state is very often exposed to vagaries of monsoon like flood and drought. The importance of groundwater in mitigating the intermittent drought condition of a rain-fed economy cannot be overemphasized. To monitor the effect caused by indiscriminate use of this precious resource on groundwater regime, Central Ground Water Board, South Eastern Region, Bhubaneswar has established about 1606 National Hydrograph Network Stations (NHNS) (open / dug wells) and 89 purpose built piezometres under Hydrology Project in the state of Orissa. The water levels are being monitored four times a year. Besides, to study the change in chemical quality of groundwater in time and space, the water samples from these NHNS are being collected once a year (Pre-monsoon) and analysed in the Water Quality Laboratory of the Region. The data of both water level and chemical analysis are being stored in computers using industry standard Relational Database Management System (RDBMS) like Oracle and MS SQL Server. This is very essential for easy retrieval and long-term sustainability of data. -

JUNE-2020 CA Monthly Civil Services Magazine.Pdf

CIVIL SERVICES MONTHLY JUNE 2020 Civil Services Board (CSB) Suspend sex test rules Amendments to the Essential Commodities Act National Productivity Council (NPC) ‘Country of Origin’ must on GeM platform Periodic Labour Force Survey Extreme Helium Star (EHe) Global Partnership on Artificial Intelligence (GPAI) Deep Submergence Rescue Vehicle (DSRV) Complex Assessment of Climate Change over the Indian Region CIVIL FOR ONE STOPSERVICES SOLUTION Haldwani Bio-Diversity Park Festival of Raja Parba Global Education Monitoring Report 2020 India won non-permanent member of UNSC in 2021-22 India bans Chinese Apps Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA) Yojana July-2020 INDEX PRELIMS POLITY AND GOVERNANCE Petition on nation’s name 1 Attorney General reappointed 2 Civil Services Board (CSB) 2 Suspend sex test rules 3 Gairsain 3 ECONOMY Amendments to the Essential Commodities Act 4 PM formalization of Micro Food Processing Enterprises (PM FME) Scheme 6 National Productivity Council (NPC) 7 PM SVANidhi 8 Animal Husbandry Infrastructure Development Fund (AHIDF) 10 ‘Country of Origin’ must on GeM platform 11 World Investment Report 2020 12 Indian Gas Exchange (IGX) 13 PK Mohanty Committee 15 SOCIETY AND HEALTH Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana 17 COVAXIN 17 Scheme for Promotion of Academic and Research Collaboration (SPARC) 18 Navigating the new normal 19 Annual TB Report 2020 20 YUKTI 2.0 21 FabiFlu 22 Aarogyapath 23 Periodic Labour Force Survey 24 SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY 25 International Asteroid Day 26 Ananya, disinfectant spray 27