Two Approaches Have Been Used to Assess the Impact of Tobacco and Alcohol Advertising on Substance Use Behaviour: Econometric Studies and Consumer Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brands, Corporations

Havana Club Bombay Saphire gin Dewar's Scottish Martini Sauza tequila Jacob's Creek Australia Mumm champagne Foster's Miller Castle rum whiskey (only for American market) Courvoisier konjak The Glenlivet 25 year old whiskey Liquor Beer Pilsner Urquell Grey Goose Wine Wine Owning Australia's biggest beer brand vodka (France) And Ready-To-Drinks (RTDs) Representing 60 countries Chives Regal 18 year old Beefeater gin Jim Beam bourbon whiskey Bacardi Foster's Group Bavaria Biggest alcohol company in the world not in the Victoria, Australia Stock market Absolut vodka Martell XO konjak Wine, beer, licquor, alcohol-free beverages Represented in 100 markets with together 200 brands Liquor World's 4th biggest liquor producer Havana club rum SABMiller Liquor 2002 South African Breweries bought American Wine World's 2nd biggest World's 4th biggest wine producer Miller Brewing Company Beam Global Spirits & Wine Wyborowa vodka 2008 takeover Vin&Sprit London Integrated in corporation Fortune Brands Johannesburg Deerfield, Illinois, USA Tanqueray gin Milwaukee, Wisconsin 80 brands in 160 countries Jameson whiskey Pernod Ricard Close cooperation with Molson Coors in USA Malibu Paris owning more than 200 brands Cuervo tequila '75 when two wine producers merged Baileys liquor Ballentine's 21 year old 2005 takeover of Allied Domecq whiskey Kahlua cofee liquor Multinational corporation that still tries to Johnny Walker Whiskey appear as family business Liquor Diageo is world leader in terms of "premium spirits" Möet Hennessey with 9 of the world's 20 biggest liquor brands Harbin Brewery Group Ltd. China's 4th biggest brewery corporation Grupo Modelo Mexico's biggest brewery corporation THE Captain Morgan rum Diageo Brahma GLOBAL London ALCOHOL INDUSTRY '97 when Grand Metropolitan and Guinness merged Smirnof vodka Anheuser-Busch InBev "global priority brands" 2004 Belgian Interbrew and Brazilian Ambev form InBev Beer (Guinness) Ca. -

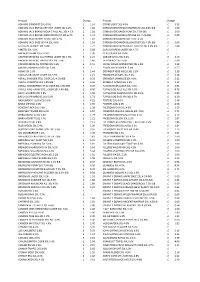

Product Change Product Change ADNAMS SPINDRIFT 30L 4.0

Product Change Product Change ADNAMS SPINDRIFT 30L 4.0% £ 1.14 COORS LIGHT 50L 4.0% £ 3.33 ADNAMS JACK BRAND DRY HOP LAGER 30L 4.2% £ 1.18 CORNISH ORCHARDS FARMHOUSE 20L 4.8% BIB £ 1.00 ADNAMS JACK BRAND MOSAIC PALE ALE 30L 4.1% £ 1.18 CORNISH ORCHARDS PEAR 20L 5.0% BIB £ 1.00 ADNAMS JACK BRAND INNOVATION IPA 30L 6.7% £ 1.42 CORNISH ORCHARDS VINTAGE 20L 7.2% BIB £ 0.98 ADNAMS BLACKSHORE STOUT 30L 4.2% £ 1.07 CORNISH ORCHARDS GOLD 50L 4.5% £ - ADNAMS JACK EASE UP IPA 30L 4.6% £ 1.16 CORNISH ORCHARDS BLUSH CIDER 20L 4.0% BIB £ 1.00 AFFLIGEM BLONDE 30L 6.8% £ 1.72 CORNISH ORCHARDS MULLED CIDER 20L 4.0% BIB £ 1.00 AMSTEL 50L 4.0% £ 2.66 CURIOUS BREW LAGER 30L 4.7% £ - ANCHOR STEAM 19.5L 4.9% £ 2.30 CURIOUS IPA 30L 4.4% £ - ANCHOR BREWING CALIFORNIA LAGER 30L 4.9% £ 2.27 DAB ORIGINAL 50L 5.0% £ 3.46 ANCHOR BREWING LIBERTY ALE 30L 5.9% £ 2.46 DE KONINCK 30L 5.0% £ 2.69 ANCHOR BREWING PORTER 30L 5.6% £ 2.41 DUVEL SINGLE FERMENTED 20L 6.8% £ 2.23 ANGRY ORCHARD CIDER 50L 5.0% £ - ELIOTS SPICY CIDER 3L 5.0% £ 0.57 ASAHI 50L 5.0% £ 3.44 ERDINGER HEFE WEISS 30L 5.3% £ 2.39 ASPALLS DRAUGHT CYDER 50L 5.5% £ 2.27 ERDINGER DUNKEL 30L 5.6% £ 2.28 ASPALL SPADGER STILL CIDER 20L 4.5% BIB £ 0.50 ERDINGER URWEISSE 30L 4.9% £ 2.22 ASPALL CYDERKYN 20L 3.8% BIB £ 0.50 ESTRELLA DAMM 50L 4.6% £ 3.37 ASPALL WOODSPRITE STILL CIDER 20L 5.8% BIB £ 0.50 FLENSBURGER LAGER 50L 4.0% £ 2.84 ASPALL KING HARRY STILL CIDER 20L 7.4% BIB £ 0.50 FLYING DOG PALE ALE 30L 5.5% £ 4.78 BACCHUS KRIEK 20L 5.8% £ 1.68 FLYING DOG RAGING BITCH 30L 8.3% £ 6.80 BACCHUS FRAMBOISE 20L 5.0% -

Lagers, Ales and Ciders

Alcohol Press Ctrl F to Search Ctrl G to find Next Occurence CODE IMAGE DESCRIPTION PACK SELL SPLIT PRICE VAT LAGERS, ALES AND CIDERS BOTTLED LAGER 103176 ASAHI JAPANESE BEER NRB 24 x 330ml 21.99 2 100390 BECKS BIER NRB 24 x 275ml 15.99 2 110766 BIRRA MESSINA SICILIAN BEER NRB 24 x 330ml 21.09 2 108634 BIRRA MORETTII ITALIAN BEER NRB 24 x 330ml 19.69 2 100658 BUDWEISER BEER AMERICAN NRB 24 x 330ml 19.59 2 100657 BUDWEISER BEER BUDVAR CZECH 24 x 330ml 22.69 2 100803 CARLSBERG LAGER SMALL BOTTLES 24 x 330ml 14.99 2 100891 CHANG THAI 5% BEER NRB 24 x 320ml 22.99 2 101220 COBRA BEER NRB 12 x 330ml 19.79 2 106197 CORONA BEER NRB 24 x 330ml 19.99 2 104974 DESPERADO'S 24 x 330ml 28.29 2 111372 DOS EQUIS XX BEER NRB 24 x 330ml 28.39 2 Alcohol Press Ctrl F to Search Ctrl G to find Next Occurence CODE IMAGE DESCRIPTION PACK SELL SPLIT PRICE VAT 102336 EFES BEER NRB TURKISH 24 x 330ml 17.39 2 104766 ESTRELLA DAM LAGER BARCELONA 24 x 330ml 20.59 2 111825 FIX BEER BOTTLES NRB SMALL 20 x 330ml 19.99 2 110760 GROLSCH PREMIUM LAGER SWINGTOP 12 x 450ml 24.29 2 111842 HELLAS PILS BEER BOTTLES NRB SMALL 24 x 330ml 17.99 2 102469 HOLSTEN PILS NRB BEER 24 x 275ml 16.99 2 102644 KEO BEER BOTTLES NRB SMALL 24 x 335ml 24.69 2 100392 KINGFISHER BEER LARGE BOTTLES 12 x 660ml 21.79 2 102686 KINGFISHER BEER NRB 24 x 330ml 19.49 2 105410 MILLER GENUINE DRAUGHT BEER 24 x 330ml 20.99 2 105451 MODELO ESPECIAL MEXICAN LAGER 4.5% 24 x 355ml 26.49 2 111690 MODELO NEGRA MEXICAN LAGER 5.3% 24 x 355ml 27.99 2 107453 MYTHOS BEER BOTTLES NRB LARGE 12 x 500ml 15.09 2 Alcohol -

Trade Mark Invalidity and Revocation Decision 0/523/01

TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF TRADE MARK REGISTRATION Nos: 1295657, 1295658, 1295659, 1328847, 1431537, 2000367, 2000371, 2045198, 2045199, 2052422, 2134017, 2146828, 2149387 & 2159254 IN THE NAME OF UDV NORTH AMERICA INC AND IN THE MATTER OF APPLICATIONS FOR REVOCATION AND DECLARATIONS OF INVALIDITY THERETO UNDER Nos: 11286 TO 11299 BY AKTSIONERNOE OBCHTCHESTVO ZAKRITOGO TIPA “TORGOVY” DOM POTOMKOV POSTAVCHTCHIKA DVORA EGO IMPERATORSKAGO VELITSCHESTVA P.A. SMIRNOVA TRADE MARKS ACT 1994 IN THE MATTER OF Trade Mark Registration Nos: 1295657, 1295658, 1295659, 1328847, 1431537, 2000367, 2000371, 2045198, 2045199, 2052422, 2134017, 2146828, 2149387 & 2159254 in the name of UDV NORTH AMERICA INC AND IN THE MATTER OF Applications for Revocation and Declarations of Invalidity thereto under Nos: 11286 to 11299 by AKTSIONERNOE OBCHTCHESTVO ZAKRITOGO TIPA “TORGOVY” DOM POTOMKOV POSTAVCHTCHIKA DVORA EGO IMPERATORSKAGO VELITSCHESTVA P.A. SMIRNOVA BACKGROUND 1. On 13 December 1999, Aktsionernoe Obchtchestvo Zakritogo Tipa “Torgovy” Dom Potomkov Postavchtchika Dvora Ego Imperatorskago Velitschestva p.a. Smirnova applied to revoke and have declared invalid fourteen registrations standing in the name of UDV North America, Inc. The registered proprietor filed counterstatements in which all of the grounds are denied. The details of the registrations in question, together with the basis of the attack against each are shown later in this decision. Suffice is to say at this point that the principal grounds of attack are similar in respect of each; that similar evidence was filed by both sides in respect of these actions and the submissions by learned Counsel were of a composite nature when the matters came to be heard on 24 and 25 April 2001. -

The Market House Inn - Bridport GOOD FOOD, GOOD BEER, GOOD CHEER Wines & Spirits

T H E M A R K E T H O U S E DRINKS MENU Ales, Lagers & Ciders COPPER ALE 4. 2.10 DORSET PALE 5.30 2.70 DORSET ORCHARDS DORSET GOLD 4.40 2.30 CARLSBERG 4.40 2.30 HAZE 4.70 2.50 IPA 4.20 2.10 BIRRA THATCHERS PALMERS 200 4.50 2.25 MORETTI 5.70 2.90 GOLD 4.80 2.40 TALLY HO! 4.60 2.40 BTL SOL 4.00 THATCHERS DRY 4.90 2.50 GUINESS 5.40 2.80 BTL HEINEKEN 0.0% 3.20 BTL OLD MOUT 5.50 Wines & Spirits WHITES 125 175 250 ROSE 125 175 250 ML ML ML ML ML ML RIO DEL MAR BIG TOP WHITE SAUVIGNON BLANC - 4.50 5.50 7.50 ZINFANDEL - AMERICAN 4.25 5.50 7.75 BCoHttIleL £E2A1N.00 Bottle £22.00 PINOT GRIGIO TERRAZZE CASSAGNAU ROSE - DELLA LUNA - ITALIAN 4.50 6.00 7.50 FRECHN 4.24 5.50 7.50 Bottle £21.00 Bottle £21.00 CASA SILVA CHARDONNAY SEMILLON PROSECCO BY THE BOTTLE - CHILEAN 4.75 6.25 8.00 DURELLO SPUMANTE 750 ML £26.00 Bottle £23.00 LUNETTA PROSECCO 200ML £8.50 CAPE HEIGHTS CHENIN BLANC - SOUTH AFRICAN 4.50 5.50 7.50 RUMS 25ML Bottle £20.00 APPLETON 4.70 REDS 125 175 250 BACARDI 2.70 ML ML ML BORSOA GARNACHA- BALLYS 4.70 SPANISH 4.00 5.00 6.80 CAPTAIN MORGANS 2.70 Bottle £19.00 DIPLOMATICO CAPE HEIGHTS SHIRAZ - 4.70 SOUTH AFRICAN 4.15 5.25 7.00 DOORLYS 4.70 Bottle £19.00 GOSLINGS 4.70 ANDES PEAK MERLOT - CHILEAN 4.50 5.50 7.25 KRAKEN 3.70 Bottle £21.00 LUGGER 4.70 ADOBE ORGANIC PINOT MOUNT GAY 3.20 NOIR - CHILEAN 4.75 6.00 8.25 Bottle £23.00 PUSSERS 4.20 FINCA DE LA NINA SAILOR JERRY 3.20 MALBEC - ARGENTINIAN 5.25 6.50 9.25 Bottle £23.00 17 West Street, Bridport, DT6 3QN - 01308459669 www.themarkethouseinn.co.uk - facebook - The Market House Inn - Bridport -

Spirits & Fabs

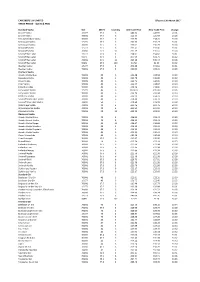

CARLSBERG UK LIMITED Effective 13th March 2017 TRADE PRICES - Spirits & FABs Standard Vodka Size ABV % Case Qty Old Trade Price New Trade Price Change Eristoff Vodka 1.5LTR 37.5 6 £40.34 £40.95 £0.61 Eristoff Vodka 700ML 37.5 6 £21.65 £21.93 £0.28 New Amsterdam Vodka 700ML 37.5 6 £17.97 £18.25 £0.28 Red Square Vodka 1.5LTR 37.5 6 £31.66 £32.27 £0.61 Red Square Vodka 700ML 37.5 6 £16.01 £16.29 £0.28 Romanoff Vodka 1.5LTR 37.5 6 £32.45 £33.06 £0.61 Romanoff Vodka 700ML 37.5 12 £15.19 £15.47 £0.28 Smirnoff Red Label 1.5LTR 37.5 6 £38.01 £38.62 £0.61 Smirnoff Red Label 3 LTR 37.5 4 £77.53 £78.75 £1.22 Smirnoff Red Label 700ML 37.5 12 £19.16 £19.44 £0.28 Smirnoff Red Label 50ML 37.5 120 £1.58 £1.60 £0.02 Vladivar Vodka 1.5LTR 37.5 6 £42.20 £42.81 £0.61 Vladivar Vodka 700ML 37.5 6 £20.03 £20.31 £0.28 Premium Vodka Absolut Vodka Blue 700ML 40 6 £24.28 £24.58 £0.30 Belvedere Vodka 700ML 40 6 £35.70 £36.00 £0.30 Chase Vodka 700ML 40 6 £39.76 £40.06 £0.30 Ciroc Vodka 700ML 40 6 £34.57 £34.87 £0.30 Finlandia Vodka 700ML 40 6 £18.56 £18.86 £0.30 Grey Goose Vodka 1.5LTR 40 6 £109.65 £110.30 £0.65 Grey Goose Vodka 700ML 40 6 £34.74 £35.04 £0.30 Ketel One Vodka 700ML 40 6 £33.93 £34.23 £0.30 Smirnoff Black Label Vodka 700ML 40 6 £28.48 £28.78 £0.30 Smirnoff Blue Label Vodka 700ML 50 7 £28.60 £28.98 £0.38 Stolichnaya Vodka 700ML 40 6 £21.46 £21.76 £0.30 Wyborowa Blue Vodka 700ML 40 6 £21.52 £21.82 £0.30 Zubrowka Vodka 700ML 40 12 £22.20 £22.50 £0.30 Flavoured Vodka Absolut Vodka Citron 700ML 40 6 £26.12 £26.42 £0.30 Absolut Kurant Vodka 700ML 40 6 £26.12 -

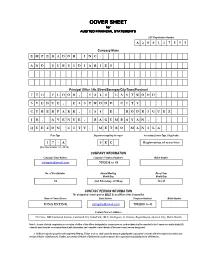

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS

COVER SHEET for AUDITED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS SEC Registration Number A 2 0 0 1 1 7 5 9 5 Company Name EMPERADORINC. ANDSUBSIDIARIES Principal Office ( No./Street/Barangay/City/Town)Province) 7TH FLOOR, 1880 EASTWOOD AVENUE,EASTWOODCITY CYBERPARK, 188 E. RODRIGUEZ JR.AVENUE,BAGUMBAYAN, QUEZONCITY,METROMANILA Form Type Department requiring the report Secondary License Type, If Applicable 1 7 - A S E C Registration of securities (For December 31, 2015) COMPANY INFORMATION Company's Email Address Company's Telephone Number/s Mobile Number [email protected] 7092038 to 41 No. of Stockholders Annual Meeting Fiscal Year Month/Day Month/Day 24 3rd Monday of May 12/31 CONTACT PERSON INFORMATION The designated contact person MUST be an Officer of the Corporation Name of Contact Person Email Address Telephone Number/s Mobile Number DINA INTING [email protected] 7092038 to 41 Contact Person's Address 7th Floor, 1880 Eastwood Avenue, Eastwood City CyberPark, 188 E. Rodriguez, Jr. Avenue, Bagumbayan, Quezon City, Metro Manila Note 1: In case of death, resgination or cessation of office of the officer designated as contact person, such incident shall be reported to the Commission within thirty (30) calendar days from the occurrence thereof with information and complete contact details of the new contact person designated. 2: All Boxes must be properly and completely filled-up. Failure to do so shall cause the delay in updating the corporation's records with the Commission and/or non- receipt of Notice of Deficiencies. Further, non-receipt of Notice of Deficiencies shall not excuse the corporation from liability for its deficiencies. -

Gurdaspur Punjab Kings Whisky 180 35 2 Ab Grains Spirits Pvt

Sr. No. WHOLESALE_VEND_NAME BRAND_NAME SIZE_CODE MRP 1 AB GRAINS SPIRITS PVT. LTD. - GURDASPUR PUNJAB KINGS WHISKY 180 35 2 AB GRAINS SPIRITS PVT. LTD. - GURDASPUR PUNJAB KINGS WHISKY 375 65 3 AB GRAINS SPIRITS PVT. LTD. - GURDASPUR PUNJAB KINGS WHISKY 750 130 4 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI AUBERGE PREMIUM VODKA GR APPLE 180 100 5 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI AUBERGE PREMIUM VODKA GR APPLE 375 200 6 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI AUBERGE PREMIUM VODKA GR APPLE 750 400 7 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGGLER BL SCOTCH WHISKY 750 1050 8 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGL. XXX MATURED RUM 180 60 9 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGL. XXX MATURED RUM 375 120 10 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI OLD SMUGL. XXX MATURED RUM 750 240 11 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI WHITE & BLUE PREMIUM WHISKY 180 100 12 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI WHITE & BLUE PREMIUM WHISKY 375 205 13 ALCOBREW DIST (I) PVT LTD. - DERABASSI WHITE & BLUE PREMIUM WHISKY 750 410 14 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA GREEN APPLE 180 145 15 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA GREEN APPLE 750 580 16 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA ORANGE 180 145 17 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORB. VODKA ORANGE 750 580 18 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 60 45 19 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 90 70 20 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 180 135 21 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 375 275 22 ALLIED BLEND&DIST P LTD - AURANGABAD WODKA GORBATSCHOW VODKA 750 550 23 A-ONE WINERIES - SANGRUR ORIGINAL CH RARE DEL WHISKY 180 50 24 A-ONE WINERIES - SANGRUR ORIGINAL CH RARE DEL WHISKY 375 100 25 A-ONE WINERIES - SANGRUR ORIGINAL CH RARE DEL WHISKY 750 200 26 BACARDI INDIA PRIVATE LTD. -

Inside This Month

october 2011 INSIDE THIS MONTH Volume 39 Issue 10 The No.1 choice for global drinks buyers ISC SPECIAL SUPPLEMENT LISTING ALL TROPHY AND MEDAL WINNERS PRE-MIXED DRINKS THERE'S MONEY IN THE MIX TEQUILA POSITIVE VIBES CAT THAT GOT Máté Csatlós, THE winner of the UK MONIN CREAM Cup 2011 ! NEW ERA FOR LIQUEURS? Drinks International 285 x 230.indd 1 29/09/11 17:50 Contents Agile Media Ltd, Zurich House, East Park, Crawley, West Sussex RH10 6AS +44(0) 1293 590040 drinksint.com 40 18 Onwards and upwards... aving survived the TFWA Cannes onslaught, it is now a question of what are we Hgoing to do this side of Christmas? I am joking of course. The DI team 30 would kill me if I were to perpetrate the idea that we are all sitting around compiling our Christmas lists. News Features Nevertheless, the Tax Free World Association 05 business News 18 cream Liqueurs exhibition is such a momentous event for everyone 08 travel retail News Healthy and low fat cream liqueurs? in the travel retail category that it takes some coming 10 What’s New Surely not? Hamish Smith reports down from. Everyone enjoyed the long days and higher temperatures, but one can assume it will move back to 28 Pre-mixed Drinks October next year as the resort will undoubtedly prefer to Analysis They are coming in under the radar. up occupancy rates in the quieter autumnal months. 14 Profile:Salvatore at Playboy Fortunately Lucy Britner has spotted them There was the usual plethora of travel retail exclusive Salvatore Calabrese has the bar at the launches aimed primarily at the rich – The Macallan recently opened Playboy Club. -

Offers PF12 SUNDAY 23RD AUGUST - SATURDAY 12TH SEPTEMBER 2020

GREAT DEALS | GREAT SERVICE | EVERYDAY Offers PF12 SUNDAY 23RD AUGUST - SATURDAY 12TH SEPTEMBER 2020 Hellmann’s Mayonnaise Kellogg’s Cereal TOP LICENSED DEALS Real Corn Flakes 8 x 430ml 6 x 550g Smirnoff Red Vodka 6 x 70cl Santa Loretta £10.99 £10.69 Prosecco 270639 988383 6 x 75cl £58.49 271580 £32.99 145104 PM £2.75 PM £2.99 Retail £8.99 PM £14.79 POR 50.0% POR 40.4% POR 26.6% POR 20.9% Walkers Taste Rockstar Energy San Miguel Icons Crisps VAS 24x330ml VAS 15 x 65g 12 x 500ml £14.49 £7.29 £7.35 889162 113135/113134/ 272176/272177/272175/ 113133/113132 271540/996985 PM £1 PM £1.29 Retail £22 POR 41.7% POR 43.0% POR 21.0% PAGESEE 28 Get Holsten Pils 24x275ml Hinched £11.99 this Summer 124074 Retail £19 @MrsHinchHome POR 24.3% Corona Extra Budweiser Carlsberg Pilsner Carlsberg Pilsner 10x330ml 10x440ml 2 x 10x440ml 18x440ml £7.49 £6.99 £11.99 £9.69 998941 271931 272193 998921 Retail £12.99 Retail £11 Retail £10 Retail £14 POR 30.8% POR 23.7% POR 28.1% POR 16.9% HELPING YOUR BUSINESS GROW WITH GREAT ADVICE AND FANTASTIC IDEAS 2 Great 50% Plus POR Deals Kellogg’s Nutri-Grain McVitie’s Jaffa Cakes Breakfast Breaks Bar 12 x 122g Raisin 24 x 45g £7.49 £6.99 272772 996828 local CHEAPER ON GO LOCAL PM 59p PM £1.29 POR 50.6% POR 51.6% San Pellegrino Classic Taste Juice Burst Jacob’s Snacks Mentos Pure Fresh Gum Aranciata/Limonata Orange/Apple/ VAS Spearmint/Fresh Mint/ 4 x 6x330ml Mango/Strawberry & Apple 30 x 50g Bubble Fresh/Tropical £9.49 12 x 500ml £10.35 24 x Pack 272216/272215 731148/671963/ £4.99 575476/855220/ £4.85 997205/997223/ 273095/273094/ -

Financial Year 2014-2015 Supplier Name Label Name No of Bottles LPL BL Offer Price Carlsberg India Pvt

Financial Year 2014-2015 Supplier Name Label Name No of Bottles LPL BL Offer Price Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Carlsberg All Malt Pr.Beer(Modified)(330) 24 0 7.92 754.07 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Carlsberg All Malt Pr.Beer(Modified)(650) 12 0 7.8 558.98 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Carlsberg All Malt Premium Can Beer(500) 24 0 12 897.9 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Tuborg Strong Premium Beer(650) 12 0 7.8 370.49 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Tuborg Strong Premium Can Beer(500) 24 0 12 607.25 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Carlsberg Elephant Strong Super Premium Beer(650) 12 0 7.8 523.17 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Carlsberg Elephant Strong Super Premium Can Beer(500) 24 0 12 897.9 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Tuborg Green Beer(650) 12 0 7.8 370.49 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Tuborg Green Beer(330) 24 0 7.92 550.58 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Tuborg Booster Strong Premium Beer(650) 12 0 7.8 457.7 Carlsberg India Pvt. Ltd. Carlsberg Elephant Extra Strong Super Premium Beer(650) 12 0 7.8 610.29 Denzong Breweries Pvt. Ltd. Denzong-9000-Strong-Beer(650)(NEW) 12 0 7.8 441.5 Denzong Breweries Pvt. Ltd. Jungle-King-12000-Real-Strong-Beer(650)(NEW) 12 0 7.8 441.5 Denzong Breweries Pvt. Ltd. Dansberg 15000 Super Strong Beer(650) 12 0 7.8 441.5 Denzong Breweries Pvt. Ltd. Dansberg Diet Super Strong Beer(650) 12 0 7.8 441.5 Devans Modern Breweries Ltd. -

From £9.00 Soft Drinks: COCKTAILS

COCKTAILS: £9.35 Kinky Martini: Absolut Vanilla, Fresh Strawberries, Coconut Cream, Strawberry Liqueur Cosmopolitan: Absolut Citron, Cointreau, Cranberry Juice Mai Tai: Bacardi, Myers, Wray & nephew, apricot liqueur, triple sec, pineapple juice Berried Alive: Vodka, strawberry & raspberry liqueur topped up with prosecco Long Island Ice Tea: Vodka, Tequila, Gin, Triple Sec, Bacardi, Lemon Juice, Pepsi Beers: £4.65 COCKTAIL JUGS: £29.70 Stella Artois Lynchburg Lemonade: Jack Daniels, Cointreau, Sol lemon juice, topped up with lemonade Asahi Sex on the beach: Vladivar vodka, peach schnapps, cranberry & orange juice Budweiser ‘66 Mai Tai: Bacardi, Myers, Wray & nephew, apricot Becks liqueur, triple sec, pineapple juice Peroni Long Island Ice Tea: Vodka, Tequila, Gin, Triple Carlsberg Sec, Bacardi, Lemon Juice, Pepsi House Spirits & Mixers: £8.50 All spirits served as a double measure (50ml) Shots: £7.70 including mixer Southern Monkey: banana liqueur, Bayleys, Southern Comfort Flat Red Line: White sambuca, tequila, Tabasco B52: Kahlua, Baileys, Grand Marnier Deluxe Spirits: from £9.00 All spirits served as a double measure (50ml) including mixer Soft Drinks: Sodas £2.65 Juices £3.85 Hildon Water Large (still or sparkling) £4.00 Small Still Water £1.65 Monster Energy Drink £4.40 All prices include 10% service charge All prices include 10% service charge CHAMPAGNES: Bottle BOTTLE SERVICE: Ace of Spades £685 Ciroc Vodka £143 Louis Roederer Cristal £450 Belvedere Vodka £132 Krug Grande Cuvee £400 Grey Goose Vodka £132 Don Perignon £300 Absolut