Purbeck-Seabird-Survey-2016.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signalling and Beacon Sites in Dorset

THE DORSET DIGGER THE NEWSLETTER OF THE DORSET DIGGERS COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY GROUP No 43 December 2016 Signalling and Beacon Sites in Dorset Richard Hood has kicked off this new project. He needs somemorevolunteerstohelpwith the research Introduction The ability to send or receive a message over a distance to warn of impending attack has been used to mobilise troops for defence since the Roman times. The Romans developed a system using five flags or torches to carry a simple message over short distances. This was usually used in battle to pass information out to army commanders. To carry a simple message further, a bonfire was used set on a high point, usually from a mini fort within vision of one or more other sites. This type of warning system was used during the invasion of Britain, when vexation forts could come under attack from tribes yet to be persuaded of the advantages of Roman living. Near the end of the Roman occupation signal stations were employed on the East and South coasts to warn of Saxon pirates. Roman signal stations on the NE coast of England took the form of mini forts, with a ditch and bank for defence. Black Down in Dorset, excavated by Bill Putnam and re examined by Dorset Diggers in 2016 is of this type. The Saxons appear to have had a system of inter divisible beacon sites to warn of Viking attack from the ninth century onwards. Later, beacons were erected to warn of the approach of the Spanish Armada, followed by a similar, but unused system, to warn of Napoleonic invasion. -

Purbeck-Seabird-Survey-2015.Pdf

1 Date: 6/10/2015 Version: FINAL Recommended Citation: Lake, S. (2015) Purbeck Seabird Survey 2015. Footprint Ecology/National Trust Front cover photo: Nick Hopper 2 Summary Continuing the trend set in 2014, several species of seabird breeding on the Purbeck coast increased in numbers in 2015. This is particularly welcome as the context is often one of long-term and substantial decline. Breeding Guillemot, Razorbill and Herring Gull reached their highest numbers since monitoring began (in the 1960s for auks and 2001 for gulls). Numbers of Fulmar and Cormorant also increased, although they have not returned to the peak numbers of the 1980s, and cormorant productivity remained quite high. The breeding Shag population, which typically fluctuates, also increased following a decline over the past five years. However, Great Black-backed Gull numbers declined, reinforcing the apparently downward trend of this species. Breeding numbers of Kittiwake also declined, and no chicks are thought to have fledged at the colony. The tiny puffin colony remains stable in numbers. Counts of breeding seabirds have been carried out on the Purbeck coast since the mid-1960s. This report presents data from the 2015 survey in the context of trends over the last 50 years. Species such as Razorbill, Guillemot and Puffin are thought to have been considerably more abundant in the first half of the 20th century, while Fulmar colonised and Kittiwake increased markedly during the second half of the 20th century. For a full discussion of previous Purbeck trends please see Lake et al. (2011). Seabirds breeding on the Purbeck coast include Fulmar, Cormorant, Shag, Herring Gull, Great Black- backed Gull, Kittiwake, Guillemot, Razorbill and Puffin. -

Beaches Where Dogs Are Allowed

Beaches where dogs are allowed • 1. Bowleaze Cove • 2. Chesil Beach • 3. Church Ope Cove • 4. Cogden • 5. Durdle Door West • 6. Durdle Door - East • 7. Durley Chine Bournemouth • 8. East Cliff Beach • 9. Eypemouth • 10. Fishermans Walk Bournemouth • 11. Gore Cove • 12. Harbour Lake Poole • 13. Hengistbury West • 14. Hive Beach (Burton Bradstock) • 15. Monmouth Beach Lyme Regis • 16. Mudeford Quay • 17. Mudeford Sandbank • 18. Mupe Bay • 19. Pier Beach Swanage • 20. Ringstead Bay • 21. Rockley Sands Poole • 22. South Beach Studland • 23. Southbourne Bournemouth • 24. St Gabriel’s Mouth • 25. Steamer Point Christchurch • 26. Studland - Knoll Beach • 27. Studland - Shell Bay • 28. White Nothe Please note that some beaches listed as dog friendly may still have certain restricted areas. Check the beach descriptions for further information. Beaches where dogs may be restricted • 1.Alum Chine Bournemouth • 2.Avon Beach Christchurch • 3.Boscombe Pier Bournemouth • 4.Bournemouth Pier • 5.Branksome Chine Poole • 6.Canford Cliffs Poole • 7.Charmouth • 8.Charmouth West • 9.Church Beach Lyme Regis • 10.Friars Cliff Christchurch • 11.Highcliffe • 12.Lyme Regis Beach • 13.Overcombe • 14.Preston Weymouth • 15.Sandbanks Poole • 16.Sandbanks Harbour Poole • 17.Seatown • 18.Shore Road - Sandbanks Poole • 19.Swanage • 20.Swanage North • 21.West Bay East • 22.West Bay West • 23.Weymouth Restrictions for dogs on beaches are generally seasonal with bans taking place between April/May and September. Check the beach descriptions for further information. Beaches where dogs are banned • 1.Shipstal Beach Beaches where we have no information • Castle Cove • Chapman's Pool • Chesil Cove • East Cliff Bournemouth • Greenhill Weymouth • Hengistbury Head Bournemouth • Highcliffe Castle Christchurch • Kimmeridge Bay • Lulworth Cove • Manor Steps Bournemouth • Sandsfoot Castle (Portland Harbour ) • Worbarrow Bay . -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Notes to Accompany the Malvern U3A Fieldtrip to the Dorset Coast 1-5 October 2018

Notes to accompany the Malvern U3A Fieldtrip to the Dorset Coast 1-5 October 2018 SUMMARY Travel to Lyme Regis; lunch ad hoc; 3:00 pm visit Lyme Regis Museum for Monday 01-Oct Museum tour with Chris Andrew, the Museum education officer and fossil walk guide; Arrive at our Weymouth hotel at approx. 5-5.30 pm Tuesday 02 -Oct No access to beaches in morning due to tides. Several stops on Portland and Fleet which are independent of tides Visit Lulworth Cove and Stair Hole; Poss ible visit to Durdle Door; Lunch at Wednesday 03-Oct Clavell’s Café, Kimmeridge; Visit to Etches Collection, Kimmeridge (with guided tour by Steve Etches). Return to Weymouth hotel. Thur sday 04 -Oct Burton Bradstock; Charmouth ; Bowleaze Cove Beaches are accessible in the morning. Fri day 05 -Oct Drive to Lyme Regis; g uided beach tour by Lyme Regis museum staff; Lunch ad hoc in Lyme Regis; Arrive Ledbury/Malvern in the late afternoon PICK-UP POINTS ( as per letter from Easytravel) Monday 1 Oct. Activity To Do Worcester pick-up Depart Croft Rd at 08.15 Barnards Green pick-up 08.45 Malvern Splash pick-up 08.50 Colwall Stone pick-up 09.10 Pick-ups and travel Ledbury Market House pick-up 09.30 to Lyme Regis Arrive Lyme Regis for Lunch - ad hoc 13.00 – 14.00 Visit Lyme Regis Museum where Chris Andrew from the Museum staff will take us for a tour of 15.00 to 16.30 the Geology Gallery. Depart Lyme Regis for Weymouth 16.30 Check in at Best Western Rembrandt Hotel, 17.30 Weymouth At 6.15pm , we will meet Alan Holiday , our guide for the coming week, in the Garden Lounge of the hotel prior to dinner. -

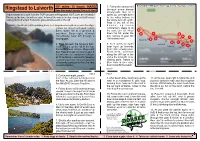

Ringstead to Lulworth Cove.Cdr

1 1 Download the FREE Sports Tracker app, to keep a log of your activities 10 / 2 miles : 4 /2 hours : HARD 7. Follow the narrow trail Ringstead to Lulworth Notes: Steep climbs & descents! Close to cliff edges! through some dense undergrowth, then as it I have started this walk from the TOP car park at Ringstead, NOT down at the beach! opens up, turn right down Driving up the lane, do not turn right, follow all the way to the top, along the flat & over a to the valley bottom. In cattle grid into the field. Follow the gravel track & park on the left. the valley, turn left, uphill. Pass to the left of the 1. Walk to the far end of the parking area, to a large wooden gate & go over the style. h o u s e , u p s o m e Follow the gravel track past Falcon rudimentary steps & at Barn, down hill to a junction & the road, turn left. Head 1 p o s t b o x . B e a r r i g h t . A l m o s t down the hill, under the 2 13 12 immediately, bear left through a tree canopy & past the Obelisk 11 10 kissing gate. "millionaires row". 4 White Nothe 3 9 5 6 2. Pass between the house & barn, 8. As it opens up again Bat's Head 7 8 head straight up the hill to the top. bear right up towards Durdle Door Stair Hole Fantastic views across Weymouth Stair Hole viewing point. -

Lulworth Cove Circular Via Tyneham and Durdle Door Lulworth Cove Circular – Wool Station Start and Finish

Lulworth Cove Circular via Tyneham and Durdle Door Lulworth Cove Circular – Wool Station Start and Finish 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 24th July 2019 Current status Document last updated Tuesday, 27th August 2019 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2008-2019, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Lulworth Cove Circular via Tyneham and Durdle Door Start & Finish: Lulworth Cove bus stop Lulworth Cove bus stop, map reference SY 822 800, is 178 km south west of Charing Cross, 16m above sea level and in Dorset. Length: 22.2 km (13.8 mi). Cumulative ascent/descent: 974m. For a shorter walk and an Alternative Start or Finish at Wool Station, see below Walk options. -

Ringstead Bay, Dorset

RINGSTEAD BAY, DORSET INTRODUCTION TO RINGSTEAD BAY THE GEOLOGY Thank you for enrolling on our fossil hunting The geology at Ringstead Bay is complex and the site is event at Ringstead Bay. frequently used by colleges and universities for field studies. This beautiful site is right on the Jurassic The main rock type in the tall, slumped cliffs is Kimmeridge Coast of Dorset and provides the fossil Clay, which is the source of many fossils. Depending on collector with opportunities to potentially beach conditions, the Ringstead Coral Bed is sometimes acquire a range of fossils from a variety of exposed, with a good range of fossils. High in the cliffs are rocks that are found here. the folded and faulted strata of the Portland Limestone Formation and the basal part of the Purbeck Formation. The site is an excellent, safe location for Fossils from these frequently appear in slipped masses or in families with older children and depending on fallen blocks at beach level. conditions, can provide bivalves and gastropods, brachiopods, coral, ammonites, Further east, the dramatic headland of White Nothe displays belemnites, echinoids and occasional marine rocks from the Upper Greensand and from both the Grey reptile bone. All provide evidence of a time Chalk Subgroup (formerly called the Lower Chalk) and the when Britain was mostly submerged beneath White Chalk Subgroup (formerly known as the Middle and tropical seas and where small islands Upper Chalk). Fossils here include echinoids, ammonites, supported the diverse life forms that existed brachiopods and bivalves. at this time. Westwards from the bay, towards Bran Point, the older The Kimmeridge Clay is the main rock type at Corallian rocks of 155 to 150 million years ago can be seen this location, with older Corallian-aged rocks as reefs and rockpools of very hard rock, packed with the to the west and younger Cretaceous Chalk at bivalve, Myophorella clavellata. -

The Geology Durdle Door, Dorset Chalk Stratigraphy, Sedimentology and Tectonic Structure New Marker Beds

Wessex OUGS Field Guide to Durdle Door, Dorset, May 2018 The Geology Durdle Door, Dorset Chalk stratigraphy, sedimentology and tectonic structure New marker beds Durdle Cove, Dorset looking west over Scratchy Bottom and Swyre Head to Bat’s Head. The line of caves at the foot of the cliff in Durdle Cove is formed on the Durdle Cove Thrust (see also Rowe 1901, Plate III, pp. 16-17). Open University Geological Society Wessex Group Field Excursion Sunday 13th May 2018 Leaders: Rory Mortimore and Jeremy Cranmer Field guide prepared by Rory Mortimore www.chalkrock.com Based on the paper Late Cretaceous stratigraphy, sediments and structure: gems of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset, England just going into press in the Proceedings of the Geologists’ Association, 2018. 1 Wessex OUGS Field Guide to Durdle Door, Dorset, May 2018 Wessex OUGS Field Trip Durdle Door, Durdle Cove, Scratchy Bottom and Bat’s Head Late Cretaceous stratigraphy, sediments and structure: gems of the Jurassic Coast of Devon and Dorset, England Introduction Extraordinary, long-distance litho-marker beds such as the Lewes and Shoreham Tubular Flints and associated marl seams and fossils (Fig.2), recognised in cliff exposures and cliff-fall boulders, are keys to unlocking the stratigraphy and tectonic structures in the Late Cretaceous (Fig.1) of the Jurassic Heritage Coast. Durdle Cove is a special gem exposing the Lewes and Seaford Chalk stratigraphy where these and new marker beds are identified and where sediments and tectonic structures provide clues to timing of movements that produced a Late Cretaceous pericline which grew into a Miocene monocline along the line of the underlying Purbeck Reverse Fault. -

Biodiversity Audit 2021

Dorset Biodiversity Audit 2021 By Dorset Environmental Records Centre For the Dorset Local Nature Partnership Dorset Environmental Records Centre At DERC we have been collating data on the wildlife of Dorset since 1976. DERC is an independent charity supported by the Dorset Wildlife Trust, Dorset Council, BCP Council, Dorset County Museum and the Environment Agency. Our role is to work to improve the data available on Dorset’s wildlife and habitats. Much of this information comes from voluntary recorders, DERC surveys, ecological consultants and the recording groups in Dorset. Our thanks to them all. If you have any comments on the Audit or information on Dorset species, the staff at DERC would be pleased to hear from you. Please contact DERC, c/o Dorset History Centre, Bridport Road, Dorset, DT1 1RP (01305) 225081 [email protected] www.derc.org.uk - 1 - Contents Page List of tables and figures 3 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 4 The Framework of the Audit 6 Strategic Nature Areas 7 Ecological Networks 9 Natural Capital & Ecosystem Services mapping 10 Habitat Accounts 11 Theme: Forestry & Woodland Lowland mixed deciduous woodland 12 Lowland beech and yew 13 Wet woodland 14 Wood pasture and parkland 15 Theme: Agriculture Hedgerows 16 Traditional orchards 17 Arable field margins 18 Lowland meadows 19 Lowland calcareous grassland 20 Lowland dry acid grassland 21 Lowland heathland 22 Purple moor-grass & rush pasture 23 Theme: Freshwater Coastal and floodplain grazing marsh 24 Lowland fens 25 Lowland fens – valley mires 26 Reedbeds 27 Rivers 28 Ponds 29 Oligotrophic and mesotrophic lakes 30 Open mosaic habitats on previously 31 developed land Theme: Coastal Maritime cliff and slope 32 Coastal vegetated shingle 33 Coastal sand dunes 34 Coastal salt-marsh 35 Saline lagoons 36 Glossary 37 Abbreviations 39 The Audit is supplemented by a Species Audit. -

Spatial Variability of the Purbeck-Wight Fault Zone - a Long-Lived Tectonic Element in the Southern UK

*Manuscript Click here to view linked References Spatial variability of the Purbeck-Wight Fault Zone - a long-lived tectonic element in the southern UK. 1Westhead, R.K, 1McCarthy, D., 2Collier, J. S. and 3Sanderson, D.J. 1British Geological Survey, The Lyell Centre, Research Avenue South, Edinburgh, EH14 4AP, UK. [email protected] (Corresponding author) 2Department of Earth Science and Engineering, Imperial College London, RSM Building, Prince Consort Road, London, SW7 2BP, UK. 3Faculty of Engineering and the Environment, University of Southampton, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK. Keywords: Inversion, tectonics, Alpine, Purbeck, Weymouth, Lyme Abstract New seamless onshore to offshore bedrock (1:10k scale) mapping for the Lyme Bay area is used to resolve the westward termination of the Purbeck-Wight Fault Zone (PWFZ) structure, comprising one of the most prominent, long-lived (Variscan-Cimmerian-Alpine) structural lineaments in the southern UK. The study area lies south of the Variscan Frontal Thrust and overlays the basement Variscide Rhenohercynian Zone, in a region of dominant E-W tectonic fabric and a secondary conjugate NW-SE/NE-SW fabric. The PWFZ comprises one of the E-W major structures, with a typical history including Permian to early Cretaceous growth movement (relating to basement Variscan Thrust reactivation) followed by significant Alpine (Helvetic) inversion. Previous interpretations of the PWFZ have been limited by the low resolution (1:250k scale) of the available offshore BGS mapping, and our study fills this gap. We describe a significant change in structural style of the fault zone from east to west. In the Weymouth Bay area, previous studies demonstrate the development of focussed strain associated with the PWFZ, accompanied by distributed strain, N-S fault development, and potential basement uplift in its hangingwall. -

Coastal Access Weymouth Bay Natural England’S Draft Proposals: Overview

www.naturalengland.org.uk Coastal Access Weymouth Bay Natural England’s Draft Proposals: Overview Coastal Access Report | Weymouth Bay Map A: Key map A352 Winfrith Newburgh Osmington Chaldon Herring A353 Holworth Nottington Overcombe Osmington Mills 15 11 12 13 West Lulworth 14 Ringstead A354 10 Bay 17 16 Durdle Weymouth Door Beach Lulworth WEYMOUTH Cove 9 B3156 8 N 0 1 2 3 4 Km Wyke Regis 7 © Crown copyright and database right 2010. Portland All rights reserved. Chesil Harbour × Natural England Licence No.100022021 Beach 6 5 Extent of draft proposals West 4 Bay Fortuneswell Start of stretch - Rufus Castle 3 2 Finish of stretch - Lulworth Cove A354 Extent of proposals in each chapter Easton 1 8 Southwell Roads, rivers and settlements A Roads B Roads Portland Bill Minor Roads Rivers Settlement Chapter number and title 1 Rufus Castle to Grove 10 Alexandra Gardens to Overcombe Corner 2 Grove to High Angle Battery 11 Overcombe Corner to Redcliff Point 3 High Angle Battery to the Merchant’s Incline 12 Redcliff Point to Black Head 4 The Merchant’s Incline 13 Black Head to Osmington Mills 5 The Merchant’s Incline to Hamm Beach 14 Osmington Mills to Ringstead 6 Hamm Beach 15 Ringstead to White Nothe 7 Rodwell Trail 16 White Nothe to Durdle Door 8 Sandsfoot Castle to Newton’s Cove 17 Durdle Door to Lulworth Cove 9 Newton’s Cove to Alexandra Gardens 2 Coastal Access | Weymouth Bay | Natural England’s Draft Proposals | Overview Advice on reading the report Our report is published on our website as a series of separate documents: Overview This document is called the Overview.