Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from JS Bach's

Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Johann Jacob Van Niekerk A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2014 Reading Committee: Giselle Wyers, Chair Geoffrey Boers Shannon Dudley Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2014 Johann Jacob Van Niekerk University of Washington Abstract Messiahs and Pariahs: Suffering and Social Conscience in the Passion Genre from J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) to David Lang’s the little match girl passion (2007) Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Giselle Wyers Associate Professor of Choral Music and Voice The themes of suffering and social conscience permeate the history of the sung passion genre: composers have strived for centuries to depict Christ’s suffering and the injustice of his final days. During the past eighty years, the definition of the genre has expanded to include secular protagonists, veiled and not-so-veiled socio- political commentary and increased discussion of suffering and social conscience as socially relevant themes. This dissertation primarily investigates David Lang’s Pulitzer award winning the little match girl passion, premiered in 2007. David Lang’s setting of Danish author and poet Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Little Match Girl” interspersed with text from the chorales of Johann Sebastian Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (1727) has since been performed by several ensembles in the United States and abroad, where it has evoked emotionally visceral reactions from audiences and critics alike. -

Please Note That Not All Pages Are Included. This Is Purposely Done in Order to Protect Our Property and the Work of Our Esteemed Composers

Please note that not all pages are included. This is purposely done in order to protect our property and the work of our esteemed composers. If you would like to see this work in its entirety, please order online or call us at 800-647-2117. No. 6280|Kyr|Alleluia for Peace|SATB (divisi) Alleluia for Peace for SATB Chorus (divisi) unaccompanied Alleluia! Robert Kyr Dona nobis pacem! Andante q = 60-63 pp distant pp Soprano 1 Soprano 2 Al - le - lu - ia, Al - pp distant pp Alto 1 Alto 2 Al - le - lu - ia, Al - pp distant pp p Tenor 1 Tenor 2 Al - le - lu - ia, al - le - lu - ia, pp distant pp p Baritone Bass Al - le - lu - ia, al - le - lu - ia, Andante q = 60-63 Keyboard (for rehearsal only) * The sounding women’s voices and the sounding men’s voices appear in the treble and bass staves respectively throughout. Robert Kyr Robert Kyr (b. 1952) has composed ten symphonies, three chamber symphonies, three violin concerti, and numerous works for vocal ensembles of all types. Several compact discs of his music are available: Violin Concerto Trilogy (New Albion NA126), Unseen Rain (New Albion NA075), vocal music for Ensemble Project Ars Nova; The Passion According to Four Evangelists (New Albion NA098) for soloists, chorus and orchestra (Back Bay Chorale; Beverly Taylor, conductor); and two discs recorded by Tapestry--Celestial Light: Music by Hildegard von Bingen and Robert Kyr (Telarc 80456), and The Fourth River: The Millennium Revealed (Telarc 80534). He has received commissions through Meet the Composer, National Endowment for the Arts, Paul G. -

N E W S L E T T

Harvard University Department of M usic MUSICnewsletter Vol. 17, No. 1 Winter 2016 The Last First Nights he crowd gathered in Sanders Theatre on the first of December to hear the world Harvard University premiere of Matthew Aucoin’s commis- Department of Music Tsioned work, “Its Own Accord.” Aucoin ’12, 3 Oxford Street piano, and Keir GoGwilt ’13, violin, took the Cambridge, MA 02138 stage. The audience hushed, as they had for the past 22 years, on this final day of class for Professor 617-495-2791 Thomas F. Kelly’s First Nights course. music.fas.harvard.edu The gorgeous interplay of violin and piano filled Sanders, and Kelly sat in the house, smiling. After the last chord on the piano, after the bows and the applause, Kelly took the stage. “I hate to break the spell. But consider this. INSIDE If you weren’t here, you didn’t hear it. For right now, we are the only people in the world who teaching fellows have supported First Nights. For 3 Faculty News have heard this piece.” many, it was their first teaching experience and for 4 Just Vibrations: Cheng Interview First Nights, one of Harvard’s most popular some, it was life-changing. and enduring courses, takes students through the “The most important thing you taught me experience of five premieres in the context of their is to be someone who manifests joy in what he own time and place: Monteverdi's opera L’Orfeo, does,” wrote Willam Bares (PhD 2010), in a note Handel’s Messiah, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, congratulating Kelly on his final class. -

Renaissance & Response January

Renaissance & Response POLYPHONY THEN & NOW JANUARY 21 ° 22 ° 23 AUSTIN, TEXAS 2010-2011 season 1 2 Renaissance & Response POLYPHONY THEN & NOW Early Voices Friday, January 21, 8:00 pm Pre-concert talk at 7:00 pm Craig Hella Johnson Defining Mastery Artistic Director & Conductor Saturday, January 22, 4:00 pm Pre-concert talk at 3:00 pm Robert Kyr Composer-in-Residence A Flowering in Spain Saturday, January 22, 8:00 pm Renaissance & Response is funded in part through Meet the And Then Came Bach Composer’s MetLife Creative Sunday, January 23, 3:00 pm Connections program. Pre-concert talk at 2:00 pm St. Martin’s Lutheran Church 606 W. 15th Street, Austin Season Sustaining Underwriter 3 Supporters Season Sustaining Underwriter Business & Foundation Supporters The Kodosky The The Meadows Russell Hill Rogers Foundation Mattsson-McHale Foundation Fund for the Arts Foundation The Rachael & Ben Vaughan Foundation Public Funding Agencies Conspirare is funded and supported in part by the City of Austin through the Cultural Arts Division, the Texas Commission on the Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts, which believes that a great nation deserves great art. Media Sponsors Leadership support for Meet The Composer’s MetLife Creative Connections program is generously provided by MetLife Foundation. Additional support is provided by The Amphion Foundation, Argosy Foundation Contemporary Music Fund, BMI Foundation, Inc., Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust, Aaron Copland Fund for Music, Inc., The William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, The James Irvine Foundation, Jerome Foundation, mediaThe foundation, National Endowment for the Arts, New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, New York State Council on the Arts, Pennsylvania Council on the Arts and Virgil Thomson Foundation, Ltd. -

Fritz Gearhart, Violin Fritz Gearhart

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-28-2003 Guest Artist Recital: Fritz Gearhart, violin Fritz Gearhart John Owings Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Gearhart, Fritz and Owings, John, "Guest Artist Recital: Fritz Gearhart, violin" (2003). All Concert & Recital Programs. 2951. https://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/2951 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. VISITING ARTISTS SERIES 2003-4 Fritz Gearhart, violin John Owings, piano ) Sonata in A major, Op. 30, No. 1 Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Allegro Adagio molto espressivo Allegretto con Variazioni Sonata No. 2 in D Major, Op. 94a (1944) Sergey Prokofiev (1891-1953) Mod era to Scherzo: Presto Andante Allegro con brio INTERMISSION Variations in the Name of Peace (2003) (Premiere) Robert Kyr (b. 1952) Suite for Violin and Piano William Grant Still (1895-1978) Majestically; Vigorously Slowly and expressive Rhythmically and humorously Hockett Family Recital Hall Tuesday, October 28, 2003 8:15 p.m. The Artists Violinist Fritz Gearhart has performed for audiences from coast to coast. October 26, 2003 marks his sixth appearance in Weill Recital Hall at Carnegie Hall since 1998. Several compact discs featuring Mr. Gearhart have been released in the last few years to rave reviews. A recent sampling from the press: "... a sizzling performance ... "(The Wall Street Journal), " .. -

Education Awards • Honors • Festivals • Fellowships

LUKE CARLSON, PHD CURRICULUM VITAE [email protected] www.LukeCarlsonMusic.com EDUCATION University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA Doctor of Philosophy in Music Composition (2010–2014) Dissertation Composition: The Burnished Tide (for orchestra) Dissertation Essay: Dutilleux’s Orchestra: Perspectives on Orchestration and the Musical Idea Composition studies with Jay Reise, James Primosch, and Anna Weesner Rice University, Houston, TX Master of Music in Composition (2008–2010) Composition studies with Karim Al-Zand and Anthony Brandt University of Oregon, Eugene, OR Bachelor of Music in Composition, magna cum laude, University of Oregon (2004–2007) Composition studies with Robert Kyr and David Crumb AWARDS • HONORS • FESTIVALS • FELLOWSHIPS/GRANTS Awards 2019 Copland House Residency Composition Residency, Cortland, NY, June 2019 First Prize, 2018 Symphony No. One Call for Scores Chamber orchestra commission to be premiered in Baltimore, MD, during the 2020/2021 season Edward T. Cone Composition Institute Performance of The Burnished Tide by the New Jersey Symphony Orchestra, conducted by JoAnn Falletta, July 16, 2015, Richardson Auditorium, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ Winner, Duo Cortona Prize Performance of Sound & Silence by Ari Streisfeld (vln.) and Rachel Calloway (sop.), May 25, 2018 Winner, 2016 MACRO Composition Competition Circuits for classical guitar, prize included giving a theoretical presentation on Circuits at the macro (Music Analysis Creative Research Organization) workshop in Madison, WI, June 17–18, -

School of Music 2013–2014

BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY BULLETIN OF YALE BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Periodicals postage paid New Haven ct 06520-8227 New Haven, Connecticut School of Music 2013–2014 School of Music 2013–2014 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 8 July 25, 2013 BULLETIN OF YALE UNIVERSITY Series 109 Number 8 July 25, 2013 (USPS 078-500) The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, is published seventeen times a year (one time in May and October; three times in June and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and a∞rmatively and September; four times in July; five times in August) by Yale University, 2 Whitney seeks to attract to its faculty, sta≠, and student body qualified persons of diverse back- Avenue, New Haven CT 0651o. Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut. grounds. In accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, any individual on account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, or PO Box 208227, New Haven CT 06520-8227 national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Managing Editor: Kimberly M. Goff-Crews University policy is committed to a∞rmative action under law in employment of Editor: Lesley K. Baier women, minority group members, individuals with disabilities, and covered veterans. PO Box 208230, New Haven CT 06520-8230 Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to the Director of the O∞ce for Equal Opportunity Programs, 221 Whitney Avenue, 203.432.0849. -

Robert Kyr Bio Long 2009

Robert Kyr (b. 1952) has composed twelve symphonies, three chamber symphonies, three violin concerti, and numerous works for vocal ensemble of all types, both unaccompanied and accompanied, including many large-scale works for which he wrote or co-wrote the text, including: A Time for Life (an environmental oratorio, 2007); The Passion according to Four Evangelists (1995); and three choral symphonies—From Creation Unfolding (No. 8, 1998), The Spirit of Time (No. 9, 2000), and Ah Nagasaki: Ashes into Light (No. 10, 2005). Kyr's music has been performed widely around the world and he has been commissioned by numerous ensembles, including Chanticleer (San Francisco), Cappella Romana (Portland), Cantus (Minneapolis), San Francisco Symphony Chorus, New England Philharmonic, Oregon Symphony, Yale Symphony Orchestra, Cleveland Chamber Symphony, New West Symphony (Los Angeles), Harvard-Radcliffe Collegium Musicum, Harvard Glee Club, Radcliffe Choral Society, Yale Camerata, Oregon Repertory Singers, Cappella Nova (Scotland), Revalia (Estonia), Putni (Latvia), Moscow State Chamber Choir (Russia), Ensemble Project Ars Nova, Back Bay Chorale (Boston), and San Francisco Symphony Youth Orchestra among others. Several compact discs of Kyr’s music are currently available on New Albion Records: Unseen Rain (NA 075), a disc of vocal music commissioned and recorded by Ensemble PAN (Project Arts Nova); The Passion according to Four Evangelists (NA 098), commissioned and recorded by the Back Bay Chorale (Boston) under the direction of Beverly Taylor; and Violin Concerto Trilogy (NA 126) recorded by the Third Angle New Music Ensemble with Ron Blessinger and Denise Huizenga, and the composer conducting. In addition, his music has been featured on several compilation discs recorded by women’s vocal ensemble, Tapestry (Laurie Monahan, director): Celestial Light: Music by Hildegard von Bingen and Robert Kyr (Telarc CD 80456); Faces of a Woman (MDG 344-1468); and The Fourth River: The Millennium Revealed (Telarc CD 80534). -

Classical Music Reviews & Magazine

Classical Music Reviews & Magazine - Fanfare Magazine - The Joy of Creation: An Interview w... http://www.fanfaremag.com/content/view/53692/10261/ Home Departments Classical Reviews Our Advertisers About Fanfare Contact Us Advertise Here Next Issue Contents Departments - Feature Articles Current Issue Written by Carson Cooman Contents Sunday, 26 January 2014 The Joy of Creation: An Interview with Robert Kyr BY CARSON COOMAN Robert Kyr was born in Ohio in 1952, and his life since has taken him throughout the world in a dizzying array of musical activities. Educated at Yale (B.A.), the Royal College of Music, the Listen to Audio University of Pennsylvania (M. A.), and Harvard (Ph. D.), he is Samples currently professor of composition and theory at the University of Oregon School of Music and Dance. His large composition Subscribers, training program there is renowned and has spawned a number of Enter the ambitious ancillary projects, including the Pacific Rim Gamelan, Fanfare Archive the Oregon Bach Festival Composers Symposium, and several other festivals and endeavors. Kyr is a very prolific composer Subscribers, whose catalog includes many works that are large-scale in their Renew Your dimensions, performing forces, and the topics they address. Subscription Though his musical language is undeniably of the present, his Online inspiration comes most deeply from the past. His contemporary style is quite consonant (and usually modal) in its sonority, but its Time for Life Subscribe to emotional aesthetic owes a great deal more to the rhetoric of early Audio CD Fanfare music than it does to neoromanticism or other consonant strands Cappella Romana Magazine & in the 20th- and 21st-century musical landscape. -

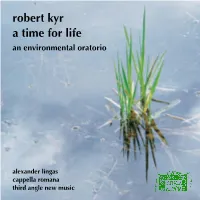

Robert Kyr a Time for Life an Environmental Oratorio

robert kyr a time for life an environmental oratorio alexander lingas cappella romana third angle new music 1 2 3 Robert Kyr (b. 1952) Cappella Romana A TIME FOR LIFE (2007) Alexander Lingas, artistic director An Environmental Oratorio LeaAnne DenBeste, soprano (S1) Stephanie Kramer, soprano (S2) Commissioned by Cappella Romana and inspired by Tuesday Kingsbury, alto (A1) the initiatives of His All-Holiness +BARTHOLOMEW Kristen Buhler, alto (A2) Archbishop of Constantinople-New Rome and Cahen Taylor, tenor (T1) Ecumenical Patriarch. Mark Powell, tenor (T2) Aaron Cain, bass (B1) David Stutz, bass (B2) Part I: Creation 16 x. Supplication V: We Pollute the Air :50 Third Angle New Music 1 i. Prologue :39 17 xi. Witness V: The Joyless Land 4:12 Ron Blessinger, violin & artistic director 2 ii. Proclaiming :35 18 xii. Supplication VI: The Dying Planet :57 Anna Schaum, viola 3 iii. Arriving 2:46 19 xiii. Witness VI: The Sacred Way 5:21 Hamilton Cheifetz, violoncello 4 iv. Praising 2:42 Part III: Remembering 5 v. Trembling 2:01 20 i. Dance of Life 2:51 6 vi. Rejoicing :57 21 ii. Canticle of Life; First Soliloquy 1:08 Part II: Forgetting 22 iii. First Canons :31 7 i. Prologue 2:23 23 iv. Chorale, First Verse 1:07 8 ii. Supplication I: We Ignore Your Word :33 24 v. Second Soliloquy 1:42 9 iii. Witness I: Look and Behold 1:58 25 vi. Chorale, Second Verse 1:13 10 iv. Supplication II: 26 vii. Second Canons :28 We Devour Your Forest :41 27 viii. Third Soliloquy 1:07 11 v. -

Robert Kyr Paradiso: Transformation and Transfiguration

Acknowledgments Recorded October 10 and 11, 2016 at the Leighton Concert Hall of the Robert Kyr DeBartolo Performing Arts Center, University of Notre Dame. Paradiso: Daniel Stein and Carmen-Helena Téllez, Producers; Gregory Geehern, Transformation assistant producer; William Maylone, Sound Engineer; Cover Art by Chantelle Snyder, after Gustave Doré; Photography by Rebecca Stutzman. and This CD project is possible with support from the University of Notre Transfiguration Dame’s Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts (ISLA). Support for the commission of Paradiso was granted by the Ann Stookey An Oratorio based on Fund for New Music (http://annstookeyfund.org/). Dante’s Divine Comedy Robert Kyr’s Paradiso was part of Journeying la Divina Commedia: Desert, Libretto by Robin Discovery, Song, a sacred music drama conceptualized by Anton Juan, Kirkpatrick Robin Kirkpatrick and Carmen-Helena Téllez for the series of Sacred Music Drama Projects at the University of Notre Dame, with sponsorship by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, and further support from the Devers Program in Dante Studies, and the Film, Television and Theatre Depart- ment at the University of Notre Dame. Notre Dame Vocale and the Sacred Music Drama Project are research projects of Carmen-Helena Téllez residing in the Sacred Music Program at Notre Dame (https://sacredmusicdrama.nd.edu/). Arwen Myers, soprano WWW.ALBANYRECORDS.COM TROY1754 ALBANY RECORDS U.S. Fernando Araujo, baritone 915 BROADWAY, ALBANY, NY 12207 TEL: 518.436.8814 FAX: 518.436.0643 Notre Dame Vocale ALBANY RECORDS U.K. BOX 137, KENDAL, CUMBRIA LA8 0XD Carmen-Helena Téllez, conductor TEL: 01539 824008 © 2018 ALBANY RECORDS MADE IN THE USA DDD WARNING: COPYRIGHT SUBSISTS IN ALL RECORDINGS ISSUED UNDER THIS LABEL. -

Circle of Breath March 2Nd and 3Rd, 2013

Circle of Breath March 2nd and 3rd, 2013 Program Order Reincarnations Samuel Barber (1910–1981) Mary Hynes Anthony O’Daly The Coolin Harmonium Chamber Singers The Lovers Barber I. Body of a woman Baritone Chamber Orchestra version by Robert Kyr, 2012 II. Lithe girl, brown girl Men, Chamber Singers Women III. In the hot depth of this summer Women IV. Close your eyes Chorus, Greg Voinier, Ben Schroeder V. The Fortunate Isles Chorus, Greg Paradis, Mickey McGrath VI. Sometimes Baritone VII. We have lost even this twilight Chorus VIII. Tonight I can write Baritone IX. Cemetery of kisses Chorus Baritone: Greg Voinier (Saturday), Mark Moliterno (Sunday) INTERMISSION A Prayer Among Friends (World Premiere) Martin A. Sedek (b. 1985) Rachel Clark, Emilie Bishop, Ken Short, Eric Roper Coronation Mass, K. 317 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756–1791) Kyrie Marilyn Kitchell, Greg Jung Gloria Laura Winslow, Megan French, Matt Shurts, Ted Roper Credo Laura Winslow, Megan French, Matt Shurts, Ted Roper Sanctus/Osanna Benedictus Marilyn Kitchell, Beth Shirley, Joe Keefe, John Lamb Agnus Dei Marilyn Kitchell Dona Nobis Pacem Marilyn Kitchell, Beth Shirley, Greg Jung, John Lamb Violin I: Ruth Zumstein Violin II: Rebecca Harris Viola: Jordan Tarantino (violin in Mozart) Cello: Marnie Kaller Bass: Jim Buchanan Harp: Merynda Adams Flute: Virginia Schulze-Johnson Oboe: Adrienne Blossey Clarinet: Dorothy Duncan Basson: Andrea Herr Horn: Lee Ann Newland, Ann Mendoker Trumpet: Andrew Filipone, Thomas Siebenhuhener Trombone: Kristin Siebenhuhener Piano: Joan Tracy Percussion: Adrienne Ostrander Samuel Barber’s career was an early and long-lived success, from his student days at Curtis and being championed by Toscanini, to the constant popularity of the youthful Adagio for Strings, until his fall from grace with his opera Anthony and Cleopatra in 1966.