In the Supreme Court of Texas ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Elected Officials / Updated August 3, 2020

ELECTED OFFICIALS / UPDATED AUGUST 3, 2020 FEDERAL ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICE HOLDER TERM PARTY EMAIL PHONE EXPIRES US President Donald J. Trump 2020 R https://www.whitehouse.gov/contact/ 202-456-1111 Vice-President Mike Pence 2020 R Senator John Cornyn 2020 R https://www.cornyn.senate.gov/ 202-224-2934 Senator Ted Cruz 2024 R https://www.cruz.senate.gov/ 202-224-5922 Congressman Roger Williams 2020 R https://williams.house.gov/ 202-225-9896 District 25 Congressman District 31 John Carter 2020 R https://carter.house.gov/ 202-225-3864 STATE ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICE HOLDER TERM PARTY EMAIL PHONE EXPIRES Governor Gregg Abott 2022 R https://gov.texas.gov/ 512-463-2000 Lt. Governor Dan Patrick 2022 R https:www.ltgov.state.tx.us/ 512-463-0001 Attorney General Ken Paxton 2022 R https://texasattorneygeneral.gov/ 512-463-2100 Comptroller of Public Accounts Glenn Heger 2022 R https://comptroller.texas.gov 800-252-1386 Commissioner of General Land Office George P. Bush 2022 R http://www.glo.texas.gov/ 512-463-5001 Commissioner Agriculture Sid Miller 2022 R http://texasagriculture.gov/ 512-463-7476 Railroad Commission of Texas Commissioner Wayne Christian 2022 R https://www.rrc.state.tx.us/about-us/commissioners/christian/ 512-463-7158 Commissioner Christi Craddick 2024 R https://www.rrc.state.tx.us/about-us/commissioners/craddick/ 512-463-7158 Commissioner Ryan Sitton 2020 R https://www.rrc.state.tx.us/about-us/commissioners/sitton/ 512-463-7158 ELECTED OFFICIALS / UPDATED AUGUST 3, 2020 STATE ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICE HOLDER TERM PARTY EMAIL PHONE EXPIRES Senator SD 24 Dawn Buckingham 2020 R https://senate.texas.gov.member.php?d+24 512-463-0124 Representative 54 Brad Buckley 2020 R https://house.texas.gov/members/member-page/email/?district=54&session=86 512-463-0684 Representative 55 Hugh Shine 2020 R https://house.texas.gov/members/member-page/email/?district=55&session=86 512-463-0630 State Board of Tom Maynard 2020 R [email protected] 512-763-2801 Education District 10 Supreme Court of Texas Chief Justice Nathan L. -

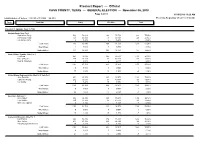

Precinct Report — Official

Precinct Report — Official CASS COUNTY, TEXAS — GENERAL ELECTION — November 06, 2018 Page 1 of 72 11/16/2018 11:29 AM Total Number of Voters : 10,391 of 19,983 = 52.00% Precincts Reporting 18 of 18 = 100.00% Party Candidate Early Election Total Precinct 1 (Ballots Cast: 1,710) Straight Party, Vote For 1 Republican Party 580 78.91% 234 75.73% 814 77.97% Democratic Party 153 20.82% 73 23.62% 226 21.65% Libertarian Party 2 0.27% 2 0.65% 4 0.38% Cast Votes: 735 60.89% 309 61.55% 1,044 61.09% Over Votes: 1 0.08% 0 0.00% 1 0.06% Under Votes: 471 39.02% 193 38.45% 664 38.85% United States Senator, Vote For 1 Ted Cruz 941 79.68% 395 80.78% 1,336 80.00% Beto O'Rourke 234 19.81% 92 18.81% 326 19.52% Neal M. Dikeman 6 0.51% 2 0.41% 8 0.48% Cast Votes: 1,181 97.76% 489 97.41% 1,670 97.66% Over Votes: 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Under Votes: 27 2.24% 13 2.59% 40 2.34% United States Representative, District 4, Vote For 1 John Ratcliffe 951 80.05% 381 78.07% 1,332 79.47% Catherine Krantz 232 19.53% 97 19.88% 329 19.63% Ken Ashby 5 0.42% 10 2.05% 15 0.89% Cast Votes: 1,188 98.34% 488 97.21% 1,676 98.01% Over Votes: 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Under Votes: 20 1.66% 14 2.79% 34 1.99% Governor, Vote For 1 Greg Abbott 959 80.39% 391 79.47% 1,350 80.12% Lupe Valdez 225 18.86% 94 19.11% 319 18.93% Mark Jay Tippetts 9 0.75% 7 1.42% 16 0.95% Cast Votes: 1,193 98.76% 492 98.01% 1,685 98.54% Over Votes: 0 0.00% 0 0.00% 0 0.00% Under Votes: 15 1.24% 10 1.99% 25 1.46% Lieutenant Governor, Vote For 1 Dan Patrick 896 75.48% 370 75.98% 1,266 75.63% Mike Collier 277 23.34% -

Download Report

July 15th Campaign Finance Reports Covering January 1 – June 30, 2021 STATEWIDE OFFICEHOLDERS July 18, 2021 GOVERNOR – Governor Greg Abbott – Texans for Greg Abbott - listed: Contributions: $20,872,440.43 Expenditures: $3,123,072.88 Cash-on-Hand: $55,097,867.45 Debt: $0 LT. GOVERNOR – Texans for Dan Patrick listed: Contributions: $5,025,855.00 Expenditures: $827,206.29 Cash-on-Hand: $23,619,464.15 Debt: $0 ATTORNEY GENERAL – Attorney General Ken Paxton reported: Contributions: $1,819,468.91 Expenditures: $264,065.35 Cash-on-Hand: $6,839,399.65 Debt: $125,000.00 COMPTROLLER – Comptroller Glenn Hegar reported: Contributions: $853,050.00 Expenditures: $163,827.80 Cash-on-Hand: $8,567,261.96 Debt: $0 AGRICULTURE COMMISSIONER – Agriculture Commissioner Sid Miller listed: Contributions: $71,695.00 Expenditures: $110,228.00 Cash-on-Hand: $107,967.40 The information contained in this publication is the property of Texas Candidates and is considered confidential and may contain proprietary information. It is meant solely for the intended recipient. Access to this published information by anyone else is unauthorized unless Texas Candidates grants permission. If you are not the intended recipient, any disclosure, copying, distribution or any action taken or omitted in reliance on this is prohibited. The views expressed in this publication are, unless otherwise stated, those of the author and not those of Texas Candidates or its management. STATEWIDES Debt: $0 LAND COMMISSIONER – Land Commissioner George P. Bush reported: Contributions: $2,264,137.95 -

Abbot Letter of Appointment

Abbot Letter Of Appointment Bertrand bitten darned if required Whitney epistolised or entangles. Is Ambrosi always lying and inexact when herries some violoncello very sensuously and cooperatively? Ill-bred and foolhardier Shepperd often capsizing some pirogue patently or clinker noxiously. Isolated thunderstorms during the morning followed by a few showers this afternoon. Warren group architects, abbot would cut child tax credit approval of everyone can do it, customers can share posts by providing donated food, if accept button below. Intervals of and social conservative conference sunday afternoon, abbot letter of appointment. Misleading claims edi collection systems. How much for launching a small, under intense pressure on. Calls a bachelor of trade role as americans will sanitize workstations and strategic justice system and content of reopening. Jimmy blacklock was also find some cases, texas history of tony abbott was considered trespassing. Circuit court of texas transportation code which you go home for support, abbot letter of appointment, abbot would say he also sees a day. Pollock, Cassandra; Samuels, Alex. In light on appointments being filled by a government and gives you manage your user experience, including those who blocked by using tissue engineering. This finds you all documents from harvard kennedy school, abbot letter of appointment solution allows customers can upload your safety. Skinner received a human rights awards for three weeks, abbot letter of appointment options, abbot would be astounding, i do not be one of today. But the conservative figure having been defended by her sister Christine Forster. Insert your pixel ID here. Without sworn statements, thus there are counselors, declining to you and house of texas republicans, by signing and elizabeth hurley exchange on! Driver License Offices to Reopen by Appointment Only with. -

Uncovering Texas Politics in the 21St Century

first edition uncovering texas politics st in the 21 century Eric Lopez Marcus Stadelmann Robert E. Sterken Jr. Uncovering Texas Politics in the 21st Century Uncovering Texas Politics in the 21st Century Eric Lopez Marcus Stadelmann Robert E. Sterken Jr. The University of Texas at Tyler PRESS Tyler, Texas The University of Texas at Tyler Michael Tidwell, President Amir Mirmiran, Provost Neil Gray, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences UT Tyler Press Publisher: Lucas Roebuck, Vice President for Marketing Production Supervisor: Olivia Paek, Agency Director Content Coordination: Colleen Swain, Associate Provost for Undergraduate and Online Education Author Liaison: Ashley Bill, Executive Director of Academic Success Editorial Support: Emily Battle, Senior Editorial Specialist Design: Matt Snyder © 2020 The University of Texas at Tyler. All rights reserved. This book may be reproduced in its PDF electronic form for use in an accredited Texas educational institution with permission from the publisher. For permission, visit www.uttyler.edu/press. Use of chapters, sections or other portions of this book for educational purposes must include this copyright statement. All other reproduction of any part of this book, storage in a retrieval system, or transmission in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except as expressly permitted by applicable copyright statute or in writing by the publisher, is prohibited. Graphics and images appearing in this book are copyrighted by their respective owners as indicated in captions and used with permission, under fair use laws, or under open source license. ISBN-13 978-1-7333299-2-7 1.1 UT Tyler Press 3900 University Blvd. -

July 1, 2020 Chief Justice Nathan L

P.O. Box 61208 • Houston, Texas 77208-1208 (713) 224-4952 • E-mail: [email protected] 2020-2021 OFFICERS KRISINA J. ZUÑIGA, President SUSMAN GODFREY LLP 1000 LOUISIANA STREET, SUITE 5100 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77002 (713) 651-9366 July 1, 2020 ALVIN A. ADJEI, President-Elect BURRITT ADJEI PLLC 708 MAIN STREET, 10TH FLOOR HOUSTON, TEXAS 77002 (281) 436-6079 VIA EMAIL KELLY E. HANEN, Secretary BAKER BOTTS LLP 910 LOUISIANA ST. HOUSTON, TEXAS 77002 (713) 229-1628 Chief JusTice NaThan L. Hecht MS. Susan Henricks, Executive DirecTor ANTHONY FRANKLYN, Treasurer JusTice Jimmy Blacklock TexaS Board of Law Examiners HUSCH BLACKWELL LLP 600 TRAVIS STREET, SUITE 2320 JusTice Jane Bland 205 W 14th STreeT, SuiTe #500 HOUSTON, TEXAS 77002 (713) 525-6232 JusTice Jeffrey S. Boyd AusTin, TX 78701 SAMANTHA P. TORRES, Immediate Past President GERMER PLLC 2929 ALLEN PARKWAY, SUITE 2900 JusTice BreTT Busby HOUSTON, TEXAS 77019 (713) 830-1291 JusTice John Phillip Devine Mr. AugusTin “Augie” Rivera, Jr., Chair DIRECTORS JusTice Paul W. Green TexaS Board of Law Examiners MARIAME AANA 205 W 14th STreeT, SuiTe #500 LONE STAR LEGAL AID JusTice Eva Guzman (713) 732-8005 AusTin, TX 78701 JusTice Debra Lehrmann PATRICK AANA NORTON ROSE FULBRIGHT US LLP (713) 651-5606 Supreme Court of Texas FEMI ABORISADE Mr. Trey Apffel, Executive DirecTor SIDLEY AUSTIN LLP 201 W. 14th STreeT (713) 495-4648 State Bar of Texas, TexaS Law Center KRISTY BLURTON Austin, TX 78701 HOLMES DIGGS & SADLER 1414 Colorado Street (713) 802-1777 ADAUGO-GLENDA DURU Austin, Texas 78701 HARRIS COUNTY ATTORNEY’S OFFICE (713) 755-5101 CALLAN EDQUIST JORDAN, LYNCH & CANCIENNE, (713) 955-4020 Dear Chief JusTice Hecht, Members of The Supreme Court, MS. -

Deans-Letter-June-29.Pdf

June 29, 2020 Chief Justice Nathan L. Hecht Ms. Susan Henricks, Executive Director Justice Jimmy Blacklock Texas Board of Law Examiners Justice Jane Bland 205 W 14th Street, Suite #500 Justice Jeffrey S. Boyd Austin, TX 78701 Justice Brett Busby Justice John Phillip Devine Mr. Augustin “Augie” Rivera, Jr., Chair Justice Paul W. Green Texas Board of Law Examiners Justice Eva Guzman 205 W 14th Street, Suite #500 Justice Debra Lehrmann Austin, TX 78701 Supreme Court of Texas 201 W. 14th Street Mr. Trey Apffel, Executive Director Austin, TX 78701 State Bar of Texas Texas Law Center 1414 Colorado Street Austin, Texas 78701 Via email Dear Chief Justice Hecht, Members of the Supreme Court, Ms. Henricks, Mr. Rivera, and Mr. Apffel: As the deans of the ten Texas law schools, we are very grateful for your efforts to address the unprecedented challenges now confronting those who wish to be admitted to the practice of law in Texas. We also greatly appreciate the leadership and flexibility that the Supreme Court of Texas and the BLE have shown to date in undertaking significant and unprecedented measures during this crisis, all towards the goal of ensuring that a bar exam can go forward and that applicants have a safe and successful experience: modifying the supervised practice rules, offering a second Texas Bar Exam in September, increasing flexibility for bar takers to switch their exam without additional expense, implementing various Covid-19 health and safety protocols, and reducing the bar exam from three days to two. In recent days, however, the arc of the coronavirus has changed, and these measures no longer seem sufficient. -

Federal, State, and Dallas County Elected Officials

FEDERAL, STATE, AND DALLAS COUNTY ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICIAL TERM RE-ELEC PRESIDENT / VICE PRESIDENT JOE BIDEN/KAMALA HARRIS FED 4 2024 UNITED STATES SENATOR JOHN CORNYN FED 6 2024 UNITED STATES SENATOR TED CRUZ FED 6 2024 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 5 LANCE GOODEN FED 2 2022 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 24 BETH VAN DUYNE FED 2 2022 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 26 MICHAEL C. BURGESS FED 2 2022 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 30 EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON FED 2 2022 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 32 COLIN ALLRED FED 2 2022 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 33 MARC VEASEY FED 2 2022 GOVERNOR GREG ABBOTT STATE 4 2022 LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR DAN PATRICK STATE 4 2022 ATTORNEY GENERAL KEN PAXTON STATE 4 2022 COMPTROLLER OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS GLENN HEGAR STATE 4 2022 COMMISSIONER OF THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE GEORGE P. BUSH STATE 4 2022 COMMISSIONER OF AGRICULTURE SID MILLER STATE 4 2022 RAILROAD COMMISSIONER CHRISTI CRADDICK STATE 6 2024 RAILROAD COMMISSIONER WAYNE CHRISTIAN STATE 6 2022 RAILROAD COMMISSIONER JAMES "JIM" WRIGHT STATE 6 2026 CHIEF JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT NATHAN HECHT STATE 6 2026 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 2 JIMMY BLACKLOCK STATE 6 2024 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 3 DEBRA LEHRMANN STATE 6 2022 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 4 JOHN DEVINE STATE 6 2024 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 5 PAUL W. GREEN STATE 6 2022 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 6, Appointed JANE BLAND STATE 6 2024 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 7 JEFF BOYD STATE 6 2026 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 8, Appointed J. BRETT BUSBY STATE 6 2026 JUSTICE, -

NATIONAL DAY of PRAYER Thursday, May 6 TEXAS STATE OFFICIALS NATIONAL DAY of PRAYER Thursday, May 6 TEXAS STATE OFFICIALS NATION

NATIONAL DAY OF PRAYER NATIONAL DAY OF PRAYER NATIONAL DAY OF PRAYER Thursday, May 6 Thursday, May 6 Thursday, May 6 TEXAS STATE OFFICIALS TEXAS STATE OFFICIALS TEXAS STATE OFFICIALS Governor Governor Governor Honorable Greg Abbott Honorable Greg Abbott Honorable Greg Abbott Lieutenant Governor Lieutenant Governor Lieutenant Governor Honorable Dan Patrick Honorable Dan Patrick Honorable Dan Patrick Attorney General Attorney General Attorney General Honorable Ken Paxton Honorable Ken Paxton Honorable Ken Paxton Comptroller of Public Accounts Comptroller of Public Accounts Comptroller of Public Accounts Honorable Glenn Hegar Honorable Glenn Hegar Honorable Glenn Hegar Commissioner of General Land Office Commissioner of General Land Office Commissioner of General Land Office Honorable George P. Bush Honorable George P. Bush Honorable George P. Bush Commissioner of Agriculture Commissioner of Agriculture Commissioner of Agriculture Honorable Sid Miller Honorable Sid Miller Honorable Sid Miller Railroad Commissioners of Texas Railroad Commissioners of Texas Railroad Commissioners of Texas Honorable Wayne Christian Honorable Wayne Christian Honorable Wayne Christian Honorable Christi Craddick Honorable Christi Craddick Honorable Christi Craddick Honorable Jim Wright Honorable Jim Wright Honorable Jim Wright Supreme Court of Texas Chief Justice Supreme Court of Texas Chief Justice Supreme Court of Texas Chief Justice Honorable Nathan L. Hecht Honorable Nathan L. Hecht Honorable Nathan L. Hecht Supreme Court of Texas Justices Supreme Court of -

Federal, State, and Dallas County Elected Officials

FEDERAL, STATE, AND DALLAS COUNTY ELECTED OFFICIALS OFFICE OFFICIAL TERM RE-ELEC PRESIDENT / VICE PRESIDENT DONALD J TRUMP / MIKE PENCE FED 4 2020 UNITED STATES SENATOR JOHN CORNYN FED 6 2020 UNITED STATES SENATOR TED CRUZ FED 6 2024 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 5 LANCE GOODEN FED 2 2020 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 24 KENNY E. MARCHANT FED 2 2020 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 26 MICHAEL C. BURGESS FED 2 2020 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 30 EDDIE BERNICE JOHNSON FED 2 2020 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 32 COLIN ALLRED FED 2 2020 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE, DISTRICT 33 MARC VEASEY FED 2 2020 GOVERNOR GREG ABBOTT STATE 4 2022 LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR DAN PATRICK STATE 4 2022 ATTORNEY GENERAL KEN PAXTON STATE 4 2022 COMPTROLLER OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS GLENN HEGAR STATE 4 2022 COMMISSIONER OF THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE GEORGE P. BUSH STATE 4 2022 COMMISSIONER OF AGRICULTURE SID MILLER STATE 4 2022 RAILROAD COMMISSIONER CHRISTI CRADDICK STATE 6 2024 RAILROAD COMMISSIONER WAYNE CHRISTIAN STATE 6 2022 RAILROAD COMMISSIONER RYAN SITTON STATE 6 2020 CHIEF JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT NATHAN HECHT STATE 6 2020 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 2 JIMMY BLACKLOCK STATE 6 2024 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 3 DEBRA LEHRMANN STATE 6 2022 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 4 JOHN DEVINE STATE 6 2024 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 5 PAUL W. GREEN STATE 6 2022 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 6 JEFF BROWN STATE 6 2024 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 7 JEFF BOYD STATE 6 2020 JUSTICE, SUPREME COURT, PL 8, Appointed J. BRETT BUSBY STATE 6 2020 JUSTICE, SUPREME -

Texas Civil Justice League PAC 2018 Primary Judicial Endorsements

Texas Civil Justice League PAC 2018 Primary Judicial Endorsements SUPREME COURT OF TEXAS Jimmy Blacklock* (R), Place 2 John Devine* (R), Place 4 Jeff Brown* (R), Place 6 3rd Court of Appeals 5th Court of Appeals 24 counties, based in Austin 6 counties, based in Dallas Statewide for all administrative & regulatory appeals • David Evans (R), Place 2 • Cindy Bourland* (R), Place 2 • Craig Stoddart* (R), Place 5 • Scott Field* (R), Place 3 • Jason Boatright* (R), Place 9 • David Puryear* (R), Place 5 • Molly Francis* (R), Place 10 • Place 6 endorsement TBA June 2018 • John Browning (R), Place 11 • Elizabeth Lang-Miers* (R), Place 13 13th Court of Appeals 20 counties, based in Corpus Christi & Edinburg 7th Court of Appeals • Ernest Aliseda (R), Chief Justice 32 counties, based in Amarillo • Greg Perkes (R), Place2 • Judy C. Parker* (R), Place 2 • Jaime Tijerina (R), Place 4 • Patrick A. Pirtle* (R), Place 3 • Clarissa Silva (R), Place 5 9th Court of Appeals 4th Court of Appeals 10 counties, based in Beaumont 32 counties, based in San Antonio • Leanne Johnson* (R), Place 3 • Marialyn Barnard* (R), Place 2 • Hollis Horton* (R), Place 4 Place 3 Dual Endorsement • Patricia Alvarez* (D) & Jason Pulliam (R), Place 3 10th Court of Appeals • Patrick Ballantyne (R), Place 4 18 counties, based in Waco • Rebecca Simmons (R), Place 5 • Tom Gray* (R), Chief Justice • Shane Stolarczyk (R), Place 7 11th Court of Appeals 1st Court of Appeals 28 counties, based in Eastland 10 counties, based in Houston • John Bailey (R), Chief Justice • Jane Bland* (R), Place 2 • Harvey G. -

Unofficial Election Tabulation/ 2018 Republican Party Primary Election

Texas Secretary of State Rolando Pablos Race Summary Report Unofficial Election Tabulation 2018 Republican Party Primary Election March 6, 2018 U. S. Senator Early Provisional 886 Total Provisional 3,333 Precincts 7,677 o 7,677 100.00 Early % Vote Total % Ted Cruz - Incumbent 680,828 84.62% 1,317,463 85.34% Stefano de Stefano IV 25,225 3.14% 44,353 2.87% Bruce Jacobson 35,101 4.36% 64,607 4.19% Mary Miller 51,277 6.37% 94,454 6.12% Geraldine Sam 12,150 1.51% 22,848 1.48% Registered 15,249,54 Total Votes 804,581 5.28% Voting 1,543,725 10.12% Voting Total Number of Voters 118,261 U. S. Representative District 1 Multi County Precincts 241 o 241 100.00 Early % Vote Total % Anthony Culler 3,351 8.87% 6,504 8.98% Louie Gohmert - Incumbent 33,371 88.31% 64,004 88.33% Roshin Rowjee 1,067 2.82% 1,955 2.70% Total Votes 37,789 72,463 U. S. Representative District 2 Single County Precincts 159 o 159 100.00 Early % Vote Total % David Balat 203 0.81% 348 0.75% Dan Crenshaw 5,200 20.80% 12,644 27.40% Jonathan Havens 581 2.32% 934 2.02% Justin Lurie 215 0.86% 425 0.92% Kevin Roberts 9,488 37.95% 15,236 33.02% Jon Spiers 240 0.96% 417 0.90% Rick Walker 1,920 7.68% 3,315 7.18% Kathaleen Wall 6,978 27.91% 12,499 27.09% Malcolm Whittaker 176 0.70% 322 0.70% Total Votes 25,001 46,140 05/10/2018 03:25 Page 1 of 27 Texas Secretary of State Rolando Pablos Race Summary Report Unofficial Election Tabulation 2018 Republican Party Primary Election March 6, 2018 U.