Afterschool Programs in West Virginia Improving the Lives of the State’S Children

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Toolkit for Working with the Media

Utilizing the Media to Facilitate Social Change A Toolkit for Working with the Media WEST VIRGINIA FOUNDATION for RAPE INFORMATION and SERVICES www.fris.org 2011 Media Toolkit | 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Media Advocacy……………………………….. ……….. 3 Building a Relationship with the Media……... ……….. 3 West Virginia Media…………………………………….. 4 Tips for Working with the Media……………... ……….. 10 Letter to the Editor…………………………….. ……….. 13 Opinion Editorial (Op-Ed)…………………….. ……….. 15 Media Advisory………………………………… ……….. 17 Press/News Release………………………….. ……….. 19 Public Service Announcements……………………….. 21 Media Interviews………………………………. ……….. 22 Survivors’ Stories and the Media………………………. 23 Media Packets…………………………………. ……….. 25 Media Toolkit | 3 Media Advocacy Media advocacy can promote social change by influencing decision-makers and swaying public opinion. Organizations can use mass media outlets to change social conditions and encourage political and social intervention. When working with the media, advocates should ‘shape’ their story to incorporate social themes rather than solely focusing on individual accountability. “Develop a story that personalizes the injustice and then provide a clear picture of who is benefiting from the condition.” (Wallack et al., 1999) Merely stating that there is a problem provides no ‘call to action’ for the public. Therefore, advocates should identify a specific solution that would allow communities to take control of the issue. Sexual violence is a public health concern of social injustices. Effective Media Campaigns Local, regional or statewide campaigns can provide a forum for prevention, outreach and raising awareness to create social change. This toolkit will enhance advocates’ abilities to utilize the media for campaigns and other events. Campaigns can include: public service announcements (PSAs), awareness events (Take Back the Night; The Clothesline Project), media interviews, coordinated events at area schools or college campuses, position papers, etc. -

TRWE Fox Station Airings: Other Cities Airing TRWE

TRWE Fox Station airings: Fox 5 WNYW New York Fox 8 WVUE New Orleans Saturday 9:00 AM Saturday 11:00 AM on 8.1/ 8.2 10:30 AM Sunday 8:30 AM Fox 11 KTTV Los Angeles Saturday 8:00 AM Fox 7 KTBC Austin Saturday 10:00 AM Fox 32 WFLD Chicago Saturday 9:00 AM Fox 30 KCVU Eureka, California Saturday 11:30 AM Fox 4 KDFW Dallas Saturday 10:00 AM Fox 2, 2.1 KTVU/KICU Oakland Saturday 12:30 PM Fox 26 KRIV Houston Saturday 7:00 AM Fox 11 KMSB Tucson Saturday 8:00 AM Fox 9 KMSP Minneapolis Saturday 10:00 AM & 10:30 AM Fox 23 WPFO Portland Saturday 12:00 PM Fox 35 WOFL Orlando Sunday 10:30 AM Fox KSLR/ KEVU Eugene, OR Saturday 11:00 AM Fox 31 KDVR Denver Saturday 11:00 AM Other Cities Airing TRWE: Fox 50 WRAZ Raleigh Durham CW KWBQ Albuquerque Saturday 9:30 AM Sundays 10:00 AM CBS 7 KIRO Seattle CBS 13 KXD Fairbanks, AK Saturday 9:30 AM Sunday 1/11 4:00 PM Sunday 1/18 1:30 PM WJAL-DT 68, 16.1 Washington, DC Thursday 1/29 3:00 PM Saturday 9:30 AM Sunday 2/1-3/1 3:00 PM My TV24 WUTB Baltimore CBS DT3/DT4 KBJR Duluth, Minnesota Saturday 9:30 AM Saturday 11:30 AM CW 6 KASW Phoenix TV 68, DT 16.1 WJAL Chambersburg, PA 9:00 AM Sundays Saturday 9:30 AM My 21 KRVU Chico, CA Saturday 11:30 AM Journal Broadcasting Stations: ABC 51 KSAW Twin Falls Saturday 11:00 AM Fox 47, 47.1, 47.2 WYSM Lansing Saturday 9:30 AM ABC 6, 6.1,6.2 KIVI Boise, ID Saturday 11:00 AM Fox 4 WFTX Fort Myers Saturday 7:30 AM Equity Media Holdings Stations: All airings on Saturdays @ 9:30 AM Atlanta, GA – WSB-DT Jackson, MS – WJTV-DT Washington, DC – WJAL-DT Tri-Cities, Bristol-Kingsport – WKPT-DT3 Detroit, MI – WXYZ-DT Burlington, VT – WGMU-TV Seattle-Tacoma, WA – KIRO-DT Colorado Springs, CO – KXRM-DT St. -

Bluefield-Beckley-Oak Hill, WV

TV Station WLFB · Analog Channel 40, DTV Channel 40 · Bluefield, WV Expected Change In Coverage: Granted Construction Permit CP (solid): 1000 kW ERP at 391 m HAAT vs. Analog (dashed): 2880 kW ERP at 391 m HAAT Market: Bluefield-Beckley-Oak Hill, WV Cabell Putnam Clay Webster Kanawha Nicholas WV-2 Pocahontas Wayne Lincoln Boone Fayette Lawrence Bath WV-3 Greenbrier Mingo VA-6 Logan Martin Beckley Raleigh Alleghany Wyoming Summers Monroe KY-5 Pike Craig Floyd Mercer Botetourt McDowell Giles Roanoke Salem Buchanan Bluefield Roanoke A40 D40 Blacksburg Montgomery Bland Dickenson Tazewell Pulaski Pulaski Russell Wise VA-5 Wytheville VA-9 Franklin Wythe Floyd Smyth Washington Carroll Scott Abingdon Henry Grayson Patrick Bristol Sullivan Alleghany Mount Airy Johnson NC-13 Ashe Surry Stokes TN-1 NC-5 Rockingham Johnson City Washington Carter Wilkes Watauga 2008 HammettUnicoi & Edison, Inc. Yadkin Forsyth 10 MI 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 40 20 0 KM 20 Coverage gained after DTV transition (no symbol) No change in coverage WLFB CP Station WOAY-TV · Analog Channel 4, DTV Channel 50 · Oak Hill, WV Expected Change In Coverage: Granted Construction Permit CP (solid): 1000 kW ERP at 237 m HAAT, Network: ABC vs. Analog (dashed): 100 kW ERP at 226 m HAAT, Network: ABC Market: Bluefield-Beckley-Oak Hill, WV OH-18 Jackson Wood Vinton Meigs Ritchie Barbour Wirt WV-1 Lewis Buckhannon OH-6 Gilmer Gallia Calhoun Jackson Upshur Mason Roane Braxton WV-2 Randolph Lawrence Putnam Clay Webster Cabell Nitro Kanawha Charleston Nicholas Pocahontas Lincoln Wayne Boone Fayette -

Business Tri-Fold Brochure (Civic Design)

Economy Package HD TV Channels Local Channels WBOY ABC HD………...….507 WSVF FOX..……………502 Channels WBOY NBC HD………...….512 WSVF CBS HD… ……..504 WDTV CBS HD …………….505 WVVA CW.….…………508 WBOY ABC…...7 C-Span 3...…….94 WHSV ABC HD.……………503 WSVF Fox..………….…502 WHSV MeTV HD.…………501 ACC HD. .580 WBOY NBC…..12 Daystar..……..169 A&E HD. 539 Disney Channel HD. .. 585 AMC HD . 656 Disney XD HD. ... .586 WDTV CBS…….5 Hillsong..…….166 Animal Planet HD. .. 537 AT&T SportsNet HD . 513 Nickelodeon HD . .587 WHSV ABC…….3 HSN…………….30 BBC America HD. 565 Discovery Family Channel HD. 590 BBC World News HD . .571 Universal Kids HD. 591 BET HD. 557 C-Span HD.. 592 WHSV MeTV…..1 Juice………….167 Bravo HD. 581 C-Span 2 HD.. 593 C-Span HD. 592 TV Channel Line Up Guide C-Span 2 HD. .. 593 C-Span 3 HD. 594 WGN…………..77 NRBTV……….170 C-Span 3 HD . 594 Fusion HD . 595 CMT HD . 614 Fox News Channel HD.. .596 WMPB PBS….160 Smile of a Child. 168 CNBC HD. 600 Fox Business HD.. 597 Comedy Central HD. 545 CNBC HD . .600 Cooking Channel HD. .. 550 MVPT PBS…..161 SonLife…….….34 Crime & Investigation HD. 574 MSNBC HD . .602 Destination America HD . 570 MTV HD .. 610 WMPT PBS… 162 TBN..…………...32 Discovery Channel HD. ..535 VH1 HD. 612 Discovery Family Channel HD . .590 CMT HD. 614 Disney Channel HD . 585 RFD-TV HD .. .646 WSVF Fox……...2 Enlace....……..165 Disney XD HD. 586 Sportsman Channel HD. .. 650 DIY Network HD. 549 WSVF CBS……..4 EWTV…………..31 E! TV HD . -

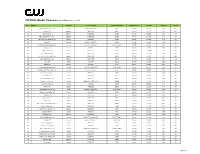

Cwplus Station List 090119.Xlsx

CW PLUS Market Clearance (as of September 1, 2019) Rank Market Time Zone On Air Call Letters Nielsen Call Letters CWPlus TV HH's TV HH's CWPlus % HD/SD 78 Harlingen-Wslco-Brnsvl, TX Central KCWT / KNVO-DT4 KCWT 249,656 351,810 71% HD 93 Savannah, GA Eastern WSAV-DT2 ESAV 328,860 328,860 100% HD 94 Charleston, SC Eastern WCBD-DT2 ECBD 257,322 320,980 80% HD 95 Myrtle Beach-Florence, SC Eastern WWMB-DT2 EWMB 184,596 281,550 66% HD 96 Burlington, VT-Plattsburgh, NY Eastern WPTZ-DT2 EPTZ 198,676 294,020 68% HD 100 Boise, ID Mountain KYUU-LP / KBOI-DT2 KYUU 264,300 264,300 100% HD 101 Fort Smith-Fay-Springdale, AR Central KHBS-DT2 / KHOG-DT2 NHBS / NHOG 281,757 292,160 96% HD 104 Fort Wayne, IN Eastern WISE-DT WISE 249,130 249,130 100% HD 105 Augusta-Aiken, GA Eastern WAGT-DT2 EAGT 192,379 249,090 77% HD 106 Johnstown-Altoona, PA Eastern WJAC-DT4 HJAC 262,840 262,840 100% HD 107 Greenville-New Bern-Wash, NC Eastern WNCT-DT2 ENCT 311,465 285,650 109% HD 108 Springfield-Holyoke, MA Eastern WWLP-DT2 EWLP 237,580 237,580 100% HD 109 Reno, NV Pacific KOLO-DT3 OOLO 263,990 263,990 100% HD 110 Lansing, MI Eastern WLAJ-DT2 ELAJ 230,333 238,990 96% HD 111 Lincoln-Hastings-Kearney, NE Central KCWH-LD / KNHL-DT3 KCWH / ONHL 210,488 263,110 80% SD 112 Tallahassee, FL-Thomasville, GA Eastern WTLF/ WTLH-DT2 WTLF 257,570 257,570 100% HD 113 Peoria-Bloomington, IL Central WEEK-DT3 GHOI 222,210 222,210 100% HD 114 Tyler-Longview, TX Central KYTX-DT2 MYTX 151,749 253,230 60% HD 115 Sioux Falls(Mitchell), SD Central KSFY-DT2 NSFY 252,660 252,660 100% HD 116 Montgomery-Selma, -

March 31, 2011 Here's Who's in the News Today from the U-M Health System, Brought to You by UMHS Public Relations

March 31, 2011 Here's who's in the news today from the U-M Health System, brought to you by UMHS Public Relations. Follow the links below to read or view newspaper, magazine, TV, radio and Web stories about our faculty, staff, students and patients. Project # of Articles Print Online Soc. Media B'cast Newswires Monthly reports 492 36 414 14 28 0 Project: Monthly reports Type Date Headline City State Audience Publication / Journalist 3/31/2011 Promising new treatment for childhood leukemia (Natalya Lyubynska) Science Daily Rockville MD 1,418,402 n/a 3/30/2011 New Cancer Drug 8:30 AM WKBD Detroit Southfield MI 3,367 n/a 3/30/2011 New Cancer Drug 8:00 AM WKBD Detroit Southfield MI 3,367 n/a 3/30/2011 New Cancer Drug 6:30 AM WWJ Detroit Southfield MI 4,838 n/a 3/30/2011 New Cancer Drug 6:20 AM WDIV Detroit Detroit MI 12,186 n/a 3/30/2011 Pain and heartache are bound together in our brains Chicago Tribune Chicago IL 2,500,000 Melissa Healy 3/30/2011 > Beaumont in Royal Oak named No. 1 hospital in Detroit by U.S. News & World Report Crains Detroit Business Detroit MI 13,200 3/30/2011 > Report: University of Michigan cut employee prescription-drug costs by $57 million over eight years Crains Detroit Business Detroit MI 13,200 3/30/2011 Japanese Authorities Consider Harvesting Backup Bone Marrow Before Sending Nuclear Plant Workers In Popular Science New York NY 584,000 Rebecca Boyle 3/30/2011 Top-selling Ann Arbor dealership Varsity Ford celebrates 30th anniversary Ann Arbor Business Review Ann Arbor MI 198,012 3/30/2011 Four Loko returns minus caffeine; U-M report touts cuts in employee prescription drug costs AnnArbor.com n/a n/a 50,000 3/30/2011 Some Women Worry More About Cancer Recurrence Than Others (Nancy Janz) BusinessWeek New York NY 6,200,000 n/a 3/29/2011 New Cancer Drug 5:10 PM WDIV Detroit Detroit MI 12,186 n/a 3/29/2011 New Cancer Drug 12:25 PM WDIV Detroit Detroit MI 12,186 n/a 3/29/2011 New cancer drug heads to clinical trials (Shaomeng Wang) Science Daily Rockville MD 1,418,402 n/a 3/29/2011 Breast cancer worries Latinas more (Nancy K. -

Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move Call

TV Broadcasters’ Impact on West Virginia Broadcasters have an impact of $5.78 billion annually on West Virginia’s economy. 12,390 Jobs 15 Commercial TV Stations Call Channel Affiliate Market Timeframe of Move WAZT-CD 10 Independent Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WAZW-CD 0 Independent Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WETA-TV 26 Public Television Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WFPT 62 Public Television Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WHAG-TV 25 Heroes & Icons Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WPXW-TV 66 ION Media Networks Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WRC-TV 4 NBC Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WWPB 31 Public Television Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 9: March 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WWPX-TV 60 ION Media Networks Washington, DC (Hagerstown, MD) (7) Phase 9: March 14, 2020 - May 1, 2020 WBYD-CD 35 Shopping Networks Pittsburgh, PA (23) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WGPT 36 Public Television Pittsburgh, PA (23) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WINP-TV 16 ION Media Networks Pittsburgh, PA (23) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WKHU-CD 60 Cozi TV Affiliation Pittsburgh, PA (23) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 WMVH-CD 26 Cozi TV Affiliation Pittsburgh, PA (23) Phase 4: June 22, 2019 - August 2, 2019 -

OHV Deaths Report

# Decedent Name News Source Reporter News Headline Hyperlink 1 Williquette Green Bay Press Gazette.com Kent Tumpus Oconto man dies in ATV crash Jan. 22 https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/local/oconto-county/2021/02/02/oconto-county-sheriff-man-dies-atv-accident/4340507001/ 2 Woolverton Idaho News.com News Staff 23-yr-old man killed in UTV crash in northern Idaho https://idahonews.com/news/local/23-year-old-man-killed-in-atv-crash-in-northern-idaho 3 Townsend KAIT 8.com News Staff 2 killed, 3 injured in UTV crash https://www.kait8.com/2021/01/25/killed-injured-atv-crash/ 4 Vazquez KAIT 8.com News Staff 2 killed, 3 injured in UTV crash https://www.kait8.com/2021/01/25/killed-injured-atv-crash/ 5 Taylor The Ada News.com News Staff Stonewall woman killed in UTV accident https://www.theadanews.com/news/local_news/stonewall-woman-killed-in-utv-accident/article_06c3c5ab-f8f6-5f2d-bf78-40d8e9dd4b9b.html 6 Unknown The Southern.com Marily Halstead Body of 39-yr-old man recovered from Ohio River https://thesouthern.com/news/local/body-of-39-year-old-man-recovered-from-ohio-river-after-atv-entered-water-saturday/article_612d6d00-b8ac-5bdc-8089-09f20493aea9.html 7 Hemmersbach LaCrosse Tribune.com News Staff Rural Hillsboro man dies in ATV crash https://lacrossetribune.com/community/vernonbroadcaster/news/update-rural-hillsboro-man-dies-in-atv-crash/article_3f9651b1-28de-5e50-9d98-e8cf73b44280.html 8 Hathaway Wood TV.com News Staff Man killed in UTV crash in Branch County https://www.woodtv.com/news/southwest-michigan/man-killed-in-utv-crash-in-branch-county/ -

Exhibit J Purchase Agreement and Disclosure Schedules

Exhibit J FILED Purchase Agreement and Disclosure Schedules 6-03-15 04:59 PM CONFIDENTIAL A1506005 Execution Version PURCHASE AND SALE AGREEMENT BY AND AMONG CEQUEL CORPORATION, ALTICE US HOLDING I S.A R.L., ALTICE US HOLDING II S.A R.L., ALTICE S.A., the Sellers parties hereto and CEQUEL III, LLC May 19, 2015 Confidential & Proprietary Subject to General Order 66-C and Public Utilities Code § 583 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ARTICLE I DEFINITIONS ............................................................................................................4 1.1 Definitions................................................................................................................4 1.2 Cross-Reference of Other Definitions ...................................................................18 ARTICLE II PURCHASE AND SALE ........................................................................................22 2.1 The Closing ............................................................................................................22 2.2 Sale and Purchase of Purchased Shares; Repurchase of Repurchased Shares .....................................................................................................................22 2.3 Downstream Merger; Post-Closing Purchaser Reorganization .............................23 2.4 Management Agreement ........................................................................................24 2.5 Closing Deliveries ..................................................................................................24 -

Tvstudy Analysis for W23de, Lima, Oh (Channel 17) Application Facility

TVSTUDY ANALYSIS FOR W23DE, LIMA, OH (CHANNEL 17) APPLICATION FACILITY tvstudy v2.2.5 (4uoc83) Database: localhost, Study: w23de01 #3485, Model: Longley-Rice Study build station data: LMS TV 2018-09-05 Proposal: W23DE01 D17 LD APP LIMA, OH File number: w23de01 Facility ID: 74373 Station data: User record Record ID: 3133 Country: U.S. Build options: Protect pre-transition records not on baseline channel Search options: Baseline record excluded if station has CP Stations potentially affected by proposal: IX Call Chan Svc Status City, State File Number Distance No WFWC-CD D16 DC CP FORT WAYNE, IN BLANK0000025862 89.0 km No WCUH-LD D16 LD LIC FORT WAYNE, IN BLANK0000008063 70.0 No WCUH-LD D16 LD CP FORT WAYNE, IN BLANK0000008088 79.5 No WDNI-CD D16 DC CP INDIANAPOLIS, IN BLANK0000034782 193.0 No WPBI-LD D16 LD LIC LAFAYETTE, IN BLANK0000016458 228.6 No WEID-LD D16 LD LIC SOUTH BEND, IN BLDTL20141105ADE 187.1 No WSMH D16 DT LIC FLINT, MI BLCDT20090804ABG 273.8 No W16DO-D D16 DC LIC CLEVELAND, OH BLANK0000001124 219.6 Yes WOSU-TV D16 DT CP COLUMBUS, OH BLANK0000033620 125.9 Yes WPTD D16 DT LIC DAYTON, OH BLEDT20090923ACN 116.0 No W16DM-D D16 LD CP LIMA, OH BNPDTL20100609AFI 36.2 No WOOH-LP D16 LD APP ZANESVILLE, OH BDFCDTT20060330ADJ 208.7 No WLCF-LD D17 LD CP DECATUR, IL BLANK0000029606 406.9 No WAND D17 DT LIC DECATUR, IL BLCDT20130709ABN 403.9 Yes WEIJ-LD D17 LD APP FORT WAYNE, IN BLANK0000054397 92.7 Yes WODP-LD D17 LD APP FORT WAYNE, IN BLANK0000052702 89.0 No WYIN D17 DT LIC GARY, IN BLEDT20040206AAA 277.4 No WISH-TV D17 LD LIC INDIANAPOLIS, -

Meeting the State's Need for Safe, Smooth and Efficient Mobility

3000 Connecticut Ave., NW, Suite 208 ● Washington, DC 20008 ● 202.466.6706 ● tripnet.org West Virginia Transportation by the Numbers: Meeting the State’s Need for Safe, Smooth and Efficient Mobility Television News Coverage - February 2017 February 16 February 20 WVNS-TV (CBS) (Bluefield) - West Virginia Tonight WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - WVVA News at 6 WVNS-DT2 (FOX) (Bluefield) - FOX 59 News WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - WVVA News at 11 WOWK-TV (CBS) (Charleston) - West Virginia Tonight WVFX-TV (FOX) (Clarksburg) - WVFX News at 10:00 WOWK-TV (CBS) (Charleston) - 13 News at 6pm WDTV-TV (CBS) (Clarksburg) - NewsChannel 5 at 11 WCHS (ABC) (Charleston) - Eyewitness News at 6 WVAH-TV (FOX) (Charleston) - Eyewitness News at 10 February 21 WOWK-TV (CBS) (Charleston) - 13 News at 5 WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - WVVA Early News Today WBOY-TV (NBC) (Clarksburg) - West Virginia Tonight WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - WVVA News Today WSAZ-TV (NBC) (Huntington) WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - WVVA News Today WHAG-TV (Washington) - West Virginia Tonight News WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - WVVA News Today WTRF-TV (CBS) (Wheeling) - 7News at 5am WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - Today WTRF-TV (CBS) (Wheeling) - 7News at 5am WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - Today's Take WTRF-TV (CBS) (Wheeling) - 7News at 6am WVVA (NBC) (Bluefield) - WVVA News at Noon WTRF-TV (CBS) (Wheeling) - 7News at 6am WDTV-TV (CBS) (Clarksburg) - Daybreak Early Edition WTRF-TV (CBS) (Wheeling) - CBS This Morning WDTV-TV (CBS) (Clarksburg) - Daybreak Early Edition WTRF-TV (CBS) (Wheeling) - CBS This Morning WDTV-TV (CBS) (Clarksburg) -

As-Filed Petition for Special Relief WDTV WVFX.Pdf

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Monongalia County, W. Va. and Preston ) MB Docket No. 12-1 County, W. Va. ) CSR-_____________ ) Petition for Special Relief for ) Modification of the Television Market of ) Stations WDTV and WVFX with ) Respect to DISH Network and ) DIRECTV ) ) To: Chief, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF Edward Hawkins Monongalia County Commission 243 High Street, Room 202 Morgantown, WV 26505 Craig Jennings Commissioner Preston County 106 W Main St #202 Kingwood, WV 26537 September 25, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY. ................................................................................ 1 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................................ 3 A. Congress Intended the STELAR Satellite Market Modification Process to Rectify “Orphan County” Situations like Monongalia and Preston Counties ................................. 3 III. WDTV AND WVFX MEET THE STATUTORY TEST FOR MARKET MODIFICATION ......................................................................................................................... 5 A. Carriage of WDTV and WVFX is Technically and Economically Feasible for DIRECTV and DISH Network ................................................................................................ 5 B. Factor 2: WDTV and WVFX Provide Extensive Local Programming to the Counties ....................................................................................................................................