Impact of Welfare Reform on the Valleys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhondda Cynon Taf - Final Proposals

RHONDDA CYNON TAF - FINAL PROPOSALS 0 1 2 3 Kilometres Scale: 1:49,400 PenderynPenderyn WardWard (704)(704) Penderyn Ward (704) HIRWAUN, PENDERYN AND RHIGOS / HIRWAUN, PENDERYN A'R RHIGOS (4,520) HIRWAUNHIRWAUN (3,832)(3,832) LLWYDCOED Hirwaun Ward LLWYDCOEDLLWYDCOED(1,032) (3,128) (1,032)(1,032) HirwaunHirwaun RHIGOSRHIGOS (688)(688) WardWard RHIGOSRHIGOSRHIGOS (688)(688) PEN-Y-WAUN (3,128)(3,128) (688) (3,128)(3,128) (2,022) PEN-Y-WAUNPEN-Y-WAUN (2,022)(2,022) Aberdare East Ward ABERDARE AND LLWYDCOED / (5,117) ABERDÂR A LLWYDCOED (12,277) Aberdare West Ward ABERDÂRABERDÂR // ABERDAREABERDARE (6,128) (11,245)(11,245) (11,245)(11,245) CWMBACH CWMBACHCWMBACH CWMBACHCWMBACH(3,189) (3,189)(3,189) Aberaman North Ward (3,768) ABERAMAN AND CWMBACH / Mountain Ash East Ward ABERAMAN A CHWMBACH (2,232) (10,320) MOUNTAIN ASH / ABERPENNAR TREHERBERT ABERAMANABERAMAN (7,131)(7,131) (5,408) (4,306) MAERDY YY MAERDYMAERDY // (2,391) Aberaman South Ward MAERDYMAERDY (3,363) ABERPENNARABERPENNAR // (2,391)(2,391) MOUNTAINMOUNTAIN ASHASH (5,408)(5,408) TREHERBERTTREHERBERT (4,306)(4,306) Mountain Ash West Ward (3,176) FERNDALE AND MAERDY / GLYNRHEDYNOG A MAERDY (5,591) PENRHIWCEIBERPENRHIWCEIBER // PENRHIW-CEIBRPENRHIW-CEIBR (4,243)(4,243) GLYNRHEDYNOGGLYNRHEDYNOG // FERNDALEFERNDALE PENRHIWCEIBER / TREORCHY / FERNDALEFERNDALE PENRHIW-CEIBR TREORCI (3,200)(3,200) UpperUpper WardWard (4,243) (5,905) (1,512)(1,512) YNYSYBWLYNYSYBWL AA CHOED-A-CWMCHOED-A-CWM // TREORCITREORCI // YNYSYBWLYNYSYBWL ANDAND COED-Y-CWMCOED-Y-CWM TREORCHYTREORCHY (3,567)(3,567) -

Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS REPORT AND PROPOSALS COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 3. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 4. DRAFT PROPOSALS 5. REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 6. ASSESSMENT 7. PROPOSALS 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT APPENDIX 1 GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDIX 2 EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 3 PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 4 MINISTER’S DIRECTIONS AND ADDITIONAL LETTER APPENDIX 5 SUMMARY OF REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO DRAFT PROPOSALS The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk FOREWORD This is our report containing our Final Proposals for Cardiff City and County Council. In January 2009, the Local Government Minister, Dr Brian Gibbons asked this Commission to review the electoral arrangements in each principal local authority in Wales. Dr Gibbons said: “Conducting regular reviews of the electoral arrangements in each Council in Wales is part of the Commission’s remit. The aim is to try and restore a fairly even spread of councillors across the local population. It is not about local government reorganisation. Since the last reviews were conducted new communities have been created in some areas and there have been shifts in population in others. This means that in some areas there is now an imbalance in the number of electors that councillors represent. -

The Pit and the Pendulum: a Cooperative Future for Work in The

Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page i POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES The Pit and the Pendulum Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page ii POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES SERIES Series editor: Ralph Fevre Previous volumes in the series: Paul Chaney, Tom Hall and Andrew Pithouse (eds), New Governance – New Democracy? Post-Devolution Wales Neil Selwyn and Stephen Gorard, The Information Age: Technology, Learning and Exclusion in Wales Graham Day, Making Sense of Wales: A Sociological Perspective Richard Rawlings, Delineating Wales: Constitutional, Legal and Administrative Aspects of National Devolution The Politics and Society in Wales Series examines issues of politics and government, and particularly the effects of devolution on policy-making and implementation, and the way in which Wales is governed as the National Assembly gains in maturity. It will also increase our knowledge and understanding of Welsh society and analyse the most important aspects of social and economic change in Wales. Where necessary, studies in the series will incorporate strong comparative elements which will allow a more fully informed appraisal of the condition of Wales. Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 02/03/04 13:34 Page iii POLITICS AND SOCIETY IN WALES The Pit and the Pendulum A COOPERATIVE FUTURE FOR WORK IN THE WELSH VALLEYS By MOLLY SCOTT CATO Published on behalf of the Social Science Committee of the Board of Celtic Studies of the University of Wales UNIVERSITY OF WALES PRESS CARDIFF 2004 Pit and the Pendulum Prelims.qxd 04/03/04 16:01 Page iv © Molly Scott Cato, 2004 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. -

2020 Flood Survey Report

1 "WE HAVE BEEN FORGOTTEN ABOUT." 2020 FLOOD SURVEY REPORT Commissioned by Leanne Wood MS and Rhondda Cynon Taf Plaid Cymru Councillors regarding flooding in Rhondda Cynon Taf in 2020 Written by C. AMOSS. 2 3 Contents 04 Statement by Leanne Wood MS 05 Introduction 06 Executive Summary 08 Pontypridd Constituency Flooding 16 Rhondda Constituency Flooding 30 Cynon Valley Constituency Flooding 34 Impact and After Effects : Conclusion 37 Recommendations 38 Appendix 4 Statement by Leanne Wood MS In February many people’s lives were turned upside down when Storm Dennis resulted in water entering their homes and businesses. Some people had been flooded before and some were flooded after that day in February, but more havoc was wreaked during that one weather event than had ever been seen in our communities. Scientists have been warning for years that the impacts of the climate crisis will be felt by more people as time goes on. As well as working to combat the causes of the climate crisis, governments – both local and national – have a duty to keep people safe and do whatever is possible to prevent people from being flooded. They should also provide support and do everything in their power to protect people and property in the future. This report analyses the survey responses of those who were flooded in Rhondda Cynon Taf and makes recommendations for action. It also shows the human cost of these floods and the toll it takes on the physical and mental health of many affected – something that has been noticeably absent from the documents produced by the authorities to date. -

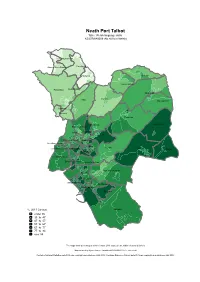

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Lower Brynamman Cwmllynfell Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Ystalyfera Onllwyn Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Trebanos Allt−wen Resolven Aberdulais Glyncorrwg Bryn−coch North Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc North Cimla Pelenna Cymmer Coedffranc Central Neath East Gwynfi Neath South Coedffranc West Briton Ferry West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Aberavon Sandfields West Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 35 35 to 47 47 to 57 57 to 67 67 to 77 77 to 84 over 84 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Lower Brynamman Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Cwmllynfell Onllwyn Ystalyfera Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Allt−wen Trebanos Resolven Aberdulais Bryn−coch North Glyncorrwg Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Coedffranc North Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc Central Neath South Pelenna Gwynfi Cimla Cymmer Neath East Briton Ferry West Coedffranc West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Sandfields West Aberavon Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 4 4 to 5 5 to 7 7 to 9 9 to 12 12 to 14 over 14 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. -

Format for Informal Cabinet Meetings

RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL CABINET 25th MARCH 2021 HIGHWAYS, TRANSPORTATION AND STRATEGIC PROJECTS SUPPLEMENTARY CAPITAL PROGRAMME 2021/22 REPORT OF THE GROUP DIRECTOR, PROSPERITY, DEVELOPMENT & FRONTLINE SERVICES IN DISCUSSION WITH THE LEADER OF THE COUNCIL, CLLR A MORGAN Author: Roger Waters, Service Director Frontline Services. Tel 01443 494702 1. PURPOSE OF THE REPORT 1.1 Further to the approval of the Council’s Three-Year Capital Programme 2021/22 - 2023/24 on 10th March 2021 at Council, this report sets out the detailed capital programme for Highways, Transportation and Strategic Projects. 2. RECOMMENDATIONS It is recommended to: 2.1 Note and approve the Supplementary Capital Programme for Highways, Transportation and Strategic Projects as detailed within this report. 2.2 Note that the current allocations are part of a 3-year capital programme and delegate authority to the Group Director, in consultation with the Leader of the Council and the Director of Finance and Digital Services, to extend activity to deliver additional projects during the financial year, where capacity exists for accelerated delivery in accordance with the purpose of the wider programme, or to suspend programmes/projects and reallocate funding to optimise delivery. 3. BACKGROUND 3.1 This report has been developed to identify commitments for RCT capital funding. The programme is impacted by a number of external factors that cannot be fully assessed at this time and this relates to both physical issues and funding. 3.2 COVID19 will continue to impact on our ability to deliver projects and programmes. Construction activity has continued to be sanctioned by Government and has evolved and adapted in the face of social distancing challenges, supply chain issues and workforce availability. -

Agenda 21 Strategy T for Neath Port Talbot

A AF N N E E W D A D Agenda 21 Strategy T for Neath Port Talbot A 1 G 2 E N D A The Plan One of the first things that became which they live, not any sort of wider apparent from the consultation administrative area. meetings was the marked differences between our communities. If problems Each of these Fora would meet are to be dealt with as local people quarterly in their “patch” facilitated would like, they cannot all be lumped by officers from the Local Authority together and dealt with across the and the Council for Voluntary Service. County in one way from centralised The forum would consist of residents offices. This therefore requires new who had attended the public mechanisms to be put into place (i) to consultation meetings, members of the listen and (ii) to deliver on a more local Community Councils, school locally sensitive system. The Agenda representatives, local Councillors, 21 Plan will be integrated into the members of local voluntary Community Strategy for Neath Port organisations indeed any local person Talbot. Guidance on the preparation who wishes to actively improve their and implementation of this new community. Any existing fora or statutory duty will be issued by the similar community groupings already National Assembly for Wales during meeting, would not be competed with the Spring of 2001. The Authority will but hopefully be involved and seek ways of addressing community enhanced. involvement and integrating this into the working of the Council, in order The remit of the forum would be to that it and its partners may be more consider the Agenda of issues that aware of and responsive to local have been collected for their particular community aspirations and issues. -

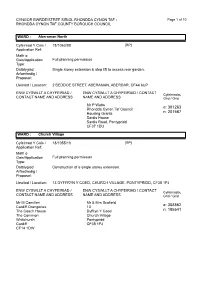

Weekly-List-Published-05-October

CYNGOR BWRDEISTREF SIRIOL RHONDDA CYNON TAF - Page 1 of 10 RHONDDA CYNON TAF COUNTY BOROUGH COUNCIL WARD : Aberaman North Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/1063/08 [RP] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Single storey extension & step lift to access rear garden. Arfaethedig / Proposal: Lleoliad / Location: 2 BEDDOE STREET, ABERAMAN, ABERDAR, CF44 6UP ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / CONTACT Cyfeirnodau CONTACT NAME AND ADDRESS NAME AND ADDRESS Grid / Grid Mr P Watts e: 301263 Rhondda Cynon Taf Council Housing Grants n: 201567 Sardis House Sardis Road, Pontypridd CF37 1DU WARD : Church Village Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/1055/10 [RP] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Construction of a single storey extension. Arfaethedig / Proposal: Lleoliad / Location: 13 DYFFRYN Y COED, CHURCH VILLAGE, PONTYPRIDD, CF38 1PJ ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / CONTACT Cyfeirnodau CONTACT NAME AND ADDRESS NAME AND ADDRESS Grid / Grid Mr M Camilleri Mr & Mrs Scofield e: 308862 Cardiff Orangeries 13 The Coach House Dyffryn Y Coed n: 185541 The Common Church Village Whitchurch Pontypridd Cardiff CF38 1PJ CF14 1DW Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/1059/10 [RP] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Single storey rear extension. Arfaethedig / Proposal: Lleoliad / Location: 1 PEN-YR-EGLWYS, CHURCH VILLAGE, PONTYPRIDD, CF38 1UA ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / ENW CYSWLLT A CHYFEIRIAD / CONTACT Cyfeirnodau CONTACT NAME AND ADDRESS NAME AND ADDRESS Grid / Grid Mr Paul Rees Mr J Burnell e: 308169 3 Heol-y-Parc 1 Pen-yr-Eglwys Efail Isaf Church Village n: 186427 Pontypridd Pontypridd CF38 1AN CF38 1UA WARD : Cilfynydd Cyfeirnod Y Cais / 18/0708/10 [JE] Application Ref: Math o Gais/Application Full planning permission Type: Datblygiad Change of use of land to extend garden curtilage (retrospective) (Amended Plans Arfaethedig / Received 14/09/18). -

Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales

LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS REPORT AND PROPOSALS COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF LOCAL GOVERNMENT BOUNDARY COMMISSION FOR WALES REVIEW OF ELECTORAL ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE COUNTY BOROUGH OF RHONDDA CYNON TAF REPORT AND PROPOSALS 1. INTRODUCTION 2. SUMMARY OF PROPOSALS 3. SCOPE AND OBJECT OF THE REVIEW 4. DRAFT PROPOSALS 5. REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO THE DRAFT PROPOSALS 6. ASSESSMENT 7. PROPOSALS 8. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 9. RESPONSES TO THIS REPORT APPENDIX 1 GLOSSARY OF TERMS APPENDIX 2 EXISTING COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 3 PROPOSED COUNCIL MEMBERSHIP APPENDIX 4 MINISTER’S DIRECTIONS AND ADDITIONAL LETTER APPENDIX 5 SUMMARY OF REPRESENTATIONS RECEIVED IN RESPONSE TO DRAFT PROPOSALS The Local Government Boundary Commission for Wales Caradog House 1-6 St Andrews Place CARDIFF CF10 3BE Tel Number: (029) 2039 5031 Fax Number: (029) 2039 5250 E-mail [email protected] www.lgbc-wales.gov.uk FOREWORD This is our report containing our Final Proposals for Rhondda Cynon Taf County Borough Council. In January 2009, the Local Government Minister, Dr Brian Gibbons asked this Commission to review the electoral arrangements in each principal local authority in Wales. Dr Gibbons said: “Conducting regular reviews of the electoral arrangements in each Council in Wales is part of the Commission’s remit. The aim is to try and restore a fairly even spread of councillors across the local population. It is not about local government reorganisation. Since the last reviews were conducted new communities have been created in some areas and there have been shifts in population in others. -

Additional Information on Flying Start from the Deputy

Table 1: Estimate of number of children aged 0 to 3 in income benefit households in each Welsh LSOA, sorted by the estimated proportion of 0-3s in income benefits households for each Local Authority cumulative estimated total of 0-3s number of 0- Number of 0- in Income proportion 3s in 3s from Benefit cumulative of 0-3s in Lower Income Small Area Households total of 0-3s, Income Super Office of National Benefit Population by Local by Local Benefit Output Area Statistics Name Lower Super Output Area Name Local Authority Name Households Estimate Authority Authority Households W01001457 Blaenau Gwent 004D Ebbw Vale North 2 Blaenau Gwent 60 80 60 80 71.6% W01001473 Blaenau Gwent 003B Sirhowy 2 Blaenau Gwent 40 65 100 145 64.1% W01001479 Blaenau Gwent 006D Tredegar Central and West 2 Blaenau Gwent 50 85 150 230 58.7% W01001459 Blaenau Gwent 007D Ebbw Vale South 1 Blaenau Gwent 25 50 175 280 50.2% W01001453 Blaenau Gwent 008D Cwmtillery 1 Blaenau Gwent 40 80 215 365 48.9% W01001469 Blaenau Gwent 005F Nantyglo 3 Blaenau Gwent 30 65 245 430 47.7% W01001471 Blaenau Gwent 001E Rassau 2 Blaenau Gwent 35 75 280 505 47.3% W01001441 Blaenau Gwent 001B Beaufort 2 Blaenau Gwent 30 65 315 570 46.8% W01001447 Blaenau Gwent 002B Brynmawr 2 Blaenau Gwent 50 110 365 680 45.4% W01001480 Blaenau Gwent 003E Tredegar Central and West 3 Blaenau Gwent 25 55 385 735 43.7% W01001474 Blaenau Gwent 003C Sirhowy 3 Blaenau Gwent 20 50 410 785 42.0% W01001456 Blaenau Gwent 004C Ebbw Vale North 1 Blaenau Gwent 25 60 430 845 41.3% W01001466 Blaenau Gwent 009C Llanhilleth -

The Parliamentary Constituencies and Assembly Electoral Regions (Wales) Order 2006

STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2006 No. 1041 REPRESENTAION OF THE PEOPLE, WALES REDISTRIBUTION OF SEATS The Parliamentary Constituencies and Assembly Electoral Regions (Wales) Order 2006 Made - - - - - 11th April 2006 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) £5.50 STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 2006 No. 1041 REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE, WALES REDISTRIBUTION OF SEATS The Parliamentary Constituencies and Assembly Electoral Regions (Wales) Order 2006 Made - - - - 11th April 2006 Coming into force in accordance with article 1(2) At the Court at Windsor Castle, the 11th day of April Present, The Queen’s Most Excellent Majesty in Council The Boundary Commission for Wales (“the Commission”) have, in accordance with section 3(1) of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986(a), submitted to the Secretary of State a report dated 31st January 2005(b) showing the parliamentary constituencies into which they recommend, in accordance with that Act, that Wales should be divided. That report also shows, as provided for by paragraph 7(2) of Schedule 1 to the Government of Wales Act 1998(c), the alterations in the electoral regions of the National Assembly for Wales which the Commission recommend(d). A draft Order in Council together with a copy of the Commission’s report was laid before Parliament by the Secretary of State to give effect, without modifications, to the recommendations contained in the report, and each House of Parliament has by resolution approved that draft. Now, therefore, Her Majesty, is pleased, by and with the advice of Her Privy Council, to make the following Order under section 4 of the Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986: (a) 1986 c.56. -

Week Ending 7Th June 2021

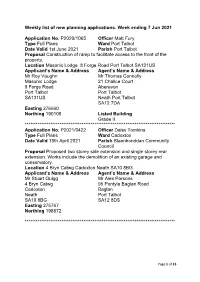

Weekly list of new planning applications. Week ending 7 Jun 2021 Application No. P2020/1065 Officer Matt Fury Type Full Plans Ward Port Talbot Date Valid 1st June 2021 Parish Port Talbot Proposal Construction of ramp to facilitate access to the front of the property. Location Masonic Lodge 8 Forge Road Port Talbot SA131US Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr Roy Vaughn Mr Thomas Connolly Masonic Lodge 21 Chalice Court 8 Forge Road Aberavon Port Talbot Port Talbot SA131US Neath Port Talbot SA12 7DA Easting 276660 Northing 190108 Listed Building Grade II ********************************************************************************** Application No. P2021/0422 Officer Daisy Tomkins Type Full Plans Ward Cadoxton Date Valid 15th April 2021 Parish Blaenhonddan Community Council Proposal Proposed two storey side extension and single storey rear extension. Works include the demolition of an existing garage and conservatory. Location 4 Bryn Catwg Cadoxton Neath SA10 8BG Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr Stuart Quigg Mr Alex Parsons 4 Bryn Catwg 95 Pentyla Baglan Road Cadoxton Baglan Neath Port Talbot SA10 8BG SA12 8DS Easting 275767 Northing 198872 ********************************************************************************** Page 1 of 13 Application No. P2021/0466 Officer Helen Bowen Type Listed Building Consent Ward Neath North Date Valid 27th April 2021 Parish Neath Town Council Proposal Listed building consent for overboard counter, installation for partition, removal of signing station and new floor box. Location 3 Windsor Road Neath SA11 1LN Applicant’s Name & Address Agent’s Name & Address Mr Ben French Mr Richard Sedgeley 62-76 Park Street Axis Architecture Southwark Talbot Chambers, London 2-6 North Church SE1 9DZ Sheffield S1 2DH Easting 275181 Conservation Area Name: Neath Town Centre Northing 197468 Listed Building Grade II ********************************************************************************** Application No.