Interface Between State and Society in Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: an Annotated Bibliography by R

Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels in Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography by R. Lee Hadden Topographic Engineering Center November 2005 US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Alexandria, VA 22315-3864 Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats, and Tunnels In Afghanistan Form Approved REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing this collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden to Department of Defense, Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports (0704-0188), 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to any penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. PLEASE DO NOT RETURN YOUR FORM TO THE ABOVE ADDRESS. 1. REPORT DATE 30-11- 2. REPORT TYPE Bibliography 3. DATES COVERED 1830-2005 2005 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER “Adits, Caves, Karizi-Qanats and Tunnels 5b. GRANT NUMBER In Afghanistan: An Annotated Bibliography” 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER HADDEN, Robert Lee 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION REPORT US Army Corps of Engineers 7701 Telegraph Road Topographic Alexandria, VA 22315- Engineering Center 3864 9.ATTN SPONSORING CEERD / MONITORINGTO I AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. -

Alessandro Monsutti Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva

Local Power and Transnational Resources: An Anthropological Perspective on Rural Rehabilitation in Afghanistan Alessandro Monsutti Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva Program in Agrarian Studies Colloquium Yale University, March 27, 2009 Le bateau ivre The Drunken Boat […] […] La tempête a béni mes éveils maritimes. The storm made bliss of my sea-borne awakenings. Plus léger qu’un bouchon j’ai dansé sur les flots Lighter than a cork, I danced on the waves Qu’on appelle rouleurs éternels de victimes, Which men call eternal rollers of victims, Dix nuits, sans regretter l’œil niais des falots! For ten nights, without once missing the foolish eye of the harbor lights! Plus douce qu’aux enfants la chair des pommes sures, L’eau verte pénétra ma coque de sapin Sweeter than the flesh of sour apples to children, Et des taches de vins bleus et des vomissures The green water penetrated my pinewood hull Me lava, dispersant gouvernail et grappin. And washed me clean of the bluish wine-stains and the splashes of vomit, Et dès lors, je me suis baigné dans le Poème Caring away both rudder and anchor. De la Mer, infusé d’astres, et lactescent, Dévorant les azurs verts; où, flottaison blême And from that time on I bathed in the Poem Et ravie, un noyé pensif parfois descend; Of the Sea, star-infused and churned into milk, Devouring the green azures; where, entranced in pallid […] flotsam, A dreaming drowned man sometimes goes down; Mais, vrai, j’ai trop pleuré! Les Aubes sont navrantes. Toute lune est atroce et tout soleil amer: […] L’âcre amour m’a gonflé de torpeurs enivrantes. -

Compilation of Country of Origin Information on Afghanistan, January 2004

Compilation of Country of Origin Information on Afghanistan, January 2004 I General Information 1. Voter Registration By the first week of January 2004, 274,964 Afghans were registered in the eight main cities. This includes 215,781 men and 59,183 women. The current rate of registration is far below the rate necessary to complete registration for elections next year. It is necessary therefore that registration teams have access to all areas of the country. This week’s figures show that Jalalabad continues to lead the turnout of Afghans registering with 29 percent of the total number of voters registered in all cities. In terms of women’s participation, Bamyan continues to have the highest proportion of women registering, with 43 percent of the total 23,403 voters registered. This figure is followed by Herat, where 29 percent of registered voters are women. 2. Loya Jirga Afghanistan's Loya Jirga has agreed on a new constitution that aims to bring stability and unity to the nation. The aim of the document is to unify the diverse Afghan nation and to prepare the ground for elections later this year. It envisages a powerful presidency - in line with the wishes of current leader Hamid Karzai - and two vice-presidents. The constitution is designed to consolidate an ethnically diverse state. The constitution also provides for women having guaranteed representation in the new parliament, as well as a powerful presidency. Agreement was reached after three weeks of heated debate that exposed the country's fragile ethnic relations. 3. General Security As a result of increased insecurity for UN and NGO staff in the South, South-East and East of Afghanistan, UNHCR has temporarily suspended the facilitation of returns from Pakistan. -

Jaghori – Wahdat – Harakat – Westernised Returnees – Shia Muslims – Apostates – Hazaras – State Protection – Employment

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: AFG31828 Country: Afghanistan Date: 7 June 2007 Keywords: Afghanistan – Kabul – Taliban – Angori – Jaghori – Wahdat – Harakat – Westernised returnees – Shia Muslims – Apostates – Hazaras – State protection – Employment This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. In which areas of Afghanistan are the Taliban currently active, in particular in Jaghori or nearby? 2. How far away is Angori from the nearest Pushtun areas? 3. Which political party or group currently controls Jaghori, in particular the Angori region? 4. Please briefly describe the background to the formation and current status of the Wahdat and Harakat parties. If Wahdat is in control, do its members target Harakat members? 5. What is the current situation in the Angori region of Jaghori for people who are members of the Harakat party? 6. What is the latest country information on the treatment of Westernised returnees to Afghanistan? 7. Is there any evidence that a Shia Muslim who no longer believes in religion would face harm in Afghanistan generally, and in the Angori region of Jaghori and in Kabul in particular? 8. Is the Taliban currently active in Kabul? Does the Taliban or any other group currently target adversely Hazaras in Kabul? Please detail. 9. Is there any effective state protection in Afghanistan generally and in Kabul in particular? 10. -

Taleban Attacks on Khas Uruzgan, Jaghori and Malestan (II): a New and Violent Push Into Hazara Areas

Taleban Attacks on Khas Uruzgan, Jaghori and Malestan (II): A new and violent push into Hazara areas Author : Ali Yawar Adili Published: 29 November 2018 Downloaded: 29 November 2018 Download URL: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/wp-admin/post.php The Taleban attacks on Hazara areas in Uruzgan and Ghazni were unprecedented in their reach and led to massive displacement. The attacks indicated a clear shift in the Taleban’s behaviour towards the Hazara areas, stimulating various hypotheses about their motives. In this second part of a series of two dispatches, AAN’s Ali Yawar Adili and Martine van Bijlert (with input from Thomas Ruttig, Fazal Muzhari and Ehsan Qaane) provide in-depth background and analysis of the attacks and their consequences. They conclude that the Taleban had long been planning to advance into the Hazara areas to expand territorial control and increase their revenues. The Taleban attacks on the Hazara areas in districts within Uruzgan and Ghazni provinces were unprecedented – at least in recent times – in terms of the number of incursions, the number of casualties and the level of coordination (three areas at more or less the same time). The initial attack on the largely self-governing Hazara enclave in the northeast of Khas Uruzgan was in response to a visit by notorious commander Abdul Hakim Shujai (more about him below) – and possibly his behaviour towards Pashtuns while he was there. At the same time, it came in the context of increased pressure by the Taleban on the Hazara population in areas that had so far largely been left alone. -

Zabul Province

Zabul Province - Reference Map ! ! nm ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sar Now Roz nm ! ! Kata Mahmodak nm nm ! Algho ! Yowlekak Hashim Sar Dana Khoneyan ! ! Mahr ! ! ! Bulagh ! Korolagh Kawchaqir Khers Ali Abad ! Ashtor ! Sar Malto Laila ! Nala ! Algak Ghajor Nakhshi ! Gho Jada ! ! Nala Chambar ! Ghat ! Shahid Gor Kash ! Mir Khan ! Baz Jailam ! Yolangak ! Qabjoy ! nm ! Mastak Sang (1) Qarkhchi Sorkh Daba ! ! ! Paitab ! Lar ! Ali Khail Pasni ! ! Huta Dahan ! nm Seya nm Sang Talawa ! ! nm Khan Pusht Mar Qoul ! Hulya ! Chehl Jowali Balagh Kar Baly Bakht Awch Markashk Ahangaran ! ! Yaso Khail Bala Bardar ! Haroon Miro ! ! Karez Karez Shakha Qoul Dahan Kasht nm Sorkh ! ! Katori nm Chal (2) ! ! (2) ! Kalan ! Kala Kalay Mohammad nm nm nmnm ! Sango nm Qoul ! ! ! Manteka nm Sabz Chob Payen Yakhak nm Seya Shamaly ! Moryani ! Khalo Neyazi ! Khail ! Neyazi Kala nm ! Bedana Buta Qouzi Talkhak ! ! Abad Chob Jaghuri Bai ! ! ! Chambar ! Wazir ! Tar Nowa ! ! Kalay nm Toot ! Khosh Qoul ! ! Darona ! ! v® ! Giro (2) ! ! Adin ! ! Watma nm Jek ! Surkhbini ! Sabz nm Qash Bodana ! Qar Gardan Sang ! !! Shash Burj Karaiz (1) ! Baba Gulak ! Chambar Dahi (2) nm Khalo Khail Hulya Khail Bar Nowroz Khail Tarinan ! nm Khushqul Sar Qoul !! ! ! ! Qoubi ! Zahid Khakraiz ! Loni nm ! Bazar ! Paige ! Zawara nm ! Khachi Khurdak ! Qabel To ! ! Karaiz Abdul Warqa ! Khail Khado Sufla ! ! Chambar ! Chaka (4) Zardi ! ! ! Qoul Dera ! ! Balagh Ghat ! Khalo Mussa Kent nm ! Jaka (1) nm nm ! Raigak Kandal ! ! Now Bala Akhound Khail ! Bashir Jaangalak nm ! ! ! Seya Qarkhachi Patra ! nm ! Shah ! Baghal -

Mines and Mineral Occurrences of Afghanistan

Mines and Mineral Occurrences of Afghanistan Compiled by G.J. Orris1 and J.D. Bliss1 Open-File Report 02-110 2002 Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY 1USGS, Tucson, Arizona TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ……………………………………………………..……... 3 DATA SOURCES, PROCESSING, AND ACCURACY ………………... 3 DATA ………………………………………………………………………….... 5 REFERENCES ………..………………………………………………………....8 APPENDIX A: Afghanistan Mines and Mineral Occurrences.. 11 TABLES Table 1. Provinces of Afghanistan .......................................................... 7 Table 2. Commodity Codes ..................................................................... 8 2 INTRODUCTION This inventory of more than 1000 mines and mineral occurrences in Afghanistan was compiled from published literature and the files of project members of the National Industrial Minerals project of the U.S. Geological Survey. The compiled data have been edited for consistency and most duplicates have been deleted. The data cover metals, industrial minerals, coal, and peat. Listings in the table represent several levels of information, including mines, mineral showings, deposits, and pegmatite fields. DATA SOURCES, PROCESSING, AND ACCURACY Data on more than 1000 Afghanistan deposits, mines, and occurrences were compiled from published literature and digital files of the project members of the National Industrial Minerals project of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). The data include information on metals, nonmetals, construction materials, coal, and peat. Three previous compilations of Afghanistan mineral resources were the dominant sources used for this effort. In 1995, the United Nation's Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific published a summary of the geology and mineral resources of Afghanistan as part of their Atlas of Mineral Resources series. -

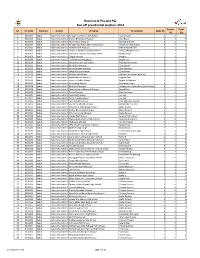

Final List of Pcs and Pss Run-Off Presidential Election, 2014

Final List of PCs and PSs Run-off presidential election, 2014 Female Total No PC Code Province District PC Name PC locatioin Male PS PS PSs 1 0101001 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan High School Asakzai lane 3 3 6 2 0101002 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mullah Mahmood Mosque Shur Bazar 3 3 6 3 0101003 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Akhir-e-Jada Mosque Maiwand Street 2 2 4 4 0101004 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Ashiqan-wa-Arefan Secondary School Se Dokan Chandawaul 3 3 6 5 0101005 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Pakhtaferoshi Mosque Pakhta forushi lane 2 3 5 6 0101006 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Daqeqi-e-Balkhi Secondary School Saraji, Ahangari Lane 3 3 6 7 0101007 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Mastoora-e-Ghoori Seconday School Babay Khudi 3 3 6 8 0101008 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Eidgah Mosque Abdgah 3 3 6 9 0101009 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Fatiha-Khana-e-Baghqazi Baghe Qazi 2 2 4 10 0101010 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Aisha-e-Durani High School Pule baghe Umumi 3 2 5 11 0101011 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Bibi Sidiqa Mosque Chendawul 2 1 3 12 0101012 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Sar-e-Gardana Mosque Sare Gardana 1 1 2 13 0101013 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Takya-Khana-e-Omomi Chendawul 3 2 5 14 0101014 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Khawja Safa Mosqe Asheqan wa Arefan Bala Joy 1 1 2 15 0101015 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Baghbankocha Mosque Baghbanlane 2 1 3 16 0101016 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Onsuri-e-Balkhi School Baghe Ali Mardan 3 2 5 17 0101017 Kabul Kabul-city district 01Imam Baqir Mosqe Hazaraha village 2 1 3 18 0101018 Kabul -

Afghanistan Topographic Maps with Background (PI42-10)

# # Sare Gulbina Bereshchenjoy # Fadzelkhe#l # Sawzsang # Nokarkhel SewakaLatek Glikhel Shinyah(1) Kot Sangin # # # Turgha # # # # # # # # # Kuz Sokhta Mushak Haydar Kalay Alibek Dara Doab ## Khwaja rawshan # Mirka# # Topur # # Mirsaleh # # # Sharifkhel Ahmadkhel Kodalak # Syahzamin # Shew Qowl # Miana # Manjarkhel Qal'eh-ye Belanda # # # Shali # Ramzi Qureh # # Safyan # # Negah Qal'a-i Surkh # Sufikhel # # Now Juy # Juy Zarin # # Asyab Darband Hasanbeg Sha # Syahsangak # # # # # # Hasankhel # # Peshkor KodayAlayarkhel Mirzabek # Bergi # # Byanan # # # Sra Kala # # # Bulaqrah # Woni Sufl Shahjoy Navor Sham Mar Bolagh # Gulmori Perong Karizak # China # # J # # # Qal'a-i Dasht # Manjway Sokhta Celgeray Zara Kala # Shater Dahane Yakhshi # # # Mianah Bed # Kolukh # Yawez Kashmur Zamuch # # Sokhtaqol # Lwar # # 67°30' # # Wersek 40' 50' 68°00' 10' 20' 30' # 40' Arab Kheyl # 50' 69°00' Payk Barikak Ghar Kuza Kala # # # 34°00' # # Sando # Kameran Khel Olsenak Sangshanda # # Markaze Saydabad # 34°00' # # # Kotaye Magh#ul Kachogha Hamzakhel # # # Nasirkhel Zangar Kala Kamar # # # Qarya-i Amir Sare Bed Sare Korya Ocha Pakpulagh Musakhel # Payendakhel Jamedkhel Pul # # # Karakat Dehe Mirdad Kunjghatu # Khwajagan # Gada'i Baraki Barak # Nawqal'a # # # Matar Ranjay Khel Durrani Wulyatak # Tajbeki Kalay #S # Yekhshi Khurd # # Wosikhel # # Gheghanqol # Badam Kala # JarchyanMohabbatkhel Saydabad Shagulkhel Ghawchqol Kushi Barik # # Ebrahihimkhel # Yekhshi Kalan Bokan # Nawer Joy # # Shadipuch # Sarsang # # # Tagaw # Qaderkhel Yamikhel # Taqi # Chehelgari(Selgari)