Business Case (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

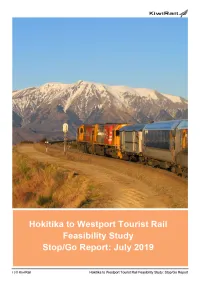

Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 1 1.1. Overview ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2. Key Findings – Markets and Visitor Hubs ......................................................................................................... 1 1.3. Key Findings – Additional Factors to Drive Visitor Growth ............................................................................... 3 1.4. Key Findings – Financial Results ...................................................................................................................... 4 1.5. Sensitivity Analysis ............................................................................................................................................ 7 1.6. Marketing Conclusions ...................................................................................................................................... 7 1.7. Project Operational Risks .................................................................................................................................. 8 1.8. Financial Conclusions ..................................................................................................................................... 10 1.9. Summary Conclusions ................................................................................................................................... -

Rail Network Investment Programme

RAIL NETWORK INVESTMENT PROGRAMME JUNE 2021 Cover: Renewing aged rail and turnouts is part of maintaining the network. This page: Upgrade work on the commuter networks is an important part of the investment programme. 2 | RAIL NETWORK INVESTMENT PROGRAMME CONTENTS 1. Foreword 4 2. Introduction and approval 5 • Rail Network Investment Programme at a glance 3. Strategic context 8 4. The national rail network today 12 5. Planning and prioritising investment 18 6. Investment – national freight and tourism network 24 7. Investment – Auckland and Wellington metro 40 8. Other investments 48 9. Delivering on this programme 50 10. Measuring success 52 11. Investment programme schedules 56 RAIL NETWORK INVESTMENT PROGRAMME | 3 1. FOREWORD KiwiRail is pleased to present this This new investment approach marks a turning point that is crucial to securing the future of rail and unlocking its inaugural Rail Network Investment full potential. Programme. KiwiRail now has certainty about the projected role of rail Rail in New Zealand is on the cusp of in New Zealand’s future, and a commitment to provide an exciting new era. the funding needed to support that role. Rail has an increasingly important role to play in the This Rail Network Investment Programme (RNIP) sets out transport sector, helping commuters and products get the tranches of work to ensure the country has a reliable, where they need to go – in particular, linking workers resilient and safe rail network. with their workplaces in New Zealand’s biggest cities, and KiwiRail is excited about taking the next steps towards connecting the nation’s exporters to the world. -

Planning Committee Meeting Held on 4/02/2020

Memorandum 20 December 2019 To: Planning Committee Independent Māori Statutory Board Subject: The Draft New Zealand Rail Plan From: Ryan Falconer Lead Transport Advisor Contact information: [email protected] Purpose 1. To provide an overview of the background to and content of the Draft New Zealand Rail Plan (the Plan), and analysis of preliminary implications of this Plan for Auckland Council and Auckland Transport. 2. To provide advice on the relevance of the Plan to Auckland and recommend providing informal feedback to the Ministry of Transport in advance of formal engagement in 2020. Summary 3. The Draft National Rail Plan provides context for proposed reform of rail network planning and investment in New Zealand, integrating rail with the balance of the land transport system and establishing a funding basis from the National Land Transport Fund. 4. The Plan is being publicised simultaneously with proposed legislative change (related amendments to the Land Transport Management Act 2003 and Land Transport Act 1988). This proposed legislative change is addressed in a separate Planning Committee memorandum. 5. The Plan emphasises the planning, funding and operations of both Auckland and Wellington’s metropolitan rail networks and prioritises addressing the needs of both passenger and freight traffic. 6. The Government has invited informal comments on the Plan. The Plan will be out for formal public engagement, alongside the Government Policy Statement on Land Transport, in 2020. However, the Government has invited informal feedback on the plan prior to this. Staff propose providing informal feedback to the Ministry of Transport in January in accordance with the points raised in this memorandum. -

LOWER NORTH ISLAND LONGER-DISTANCE ROLLING STOCK BUSINESS CASE PREPARED for GREATER WELLINGTON REGIONAL COUNCIL 2 December 2019

LOWER NORTH ISLAND LONGER-DISTANCE ROLLING STOCK BUSINESS CASE PREPARED FOR GREATER WELLINGTON REGIONAL COUNCIL 2 December 2019 This document has been prepared for the benefit of Greater Wellington Regional Council. No liability is accepted by this company or any employee or sub-consultant of this company with respect to its use by any other person. This disclaimer shall apply notwithstanding that the report may be made available to other persons for an application for permission or approval to fulfil a legal requirement. QUALITY STATEMENT PROJECT MANAGER PROJECT TECHNICAL LEAD Doug Weir Doug Weir PREPARED BY Doug Weir, Andrew Liese CHECKED BY Jamie Whittaker, Doug Weir, Deepa Seares REVIEWED BY Jamie Whittaker, Phil Peet APPROVED FOR ISSUE BY Doug Weir WELLINGTON Level 13, 80 The Terrace, Wellington 6011 PO Box 13-052, Armagh, Christchurch 8141 TEL +64 4 381 6700 REVISION SCHEDULE Authorisation Rev Date Description No. Prepared Checked Reviewed Approved by by by by 1 27/07/18 First Draft Final DW, AL JW JW DW 2 24/10/18 Updated First Draft Final DW JW JW DW Revised Draft Final (GWRC 3 05/08/19 DW DW PP DW Sustainable Transport Committee) 3 20/08/19 Updated Revised Draft Final DW DS PP DW Amended Draft Final 4 26/09/19 DW DW PP DW (GWRC Council) 5 02/12/19 Final DW DW PP DW Stantec │ Lower North Island Longer-Distance Rolling Stock Business Case │ 2 December 2019 Status: Final │ Project No.: 310200204 │ Our ref: 310200204 191202 Lower North Island Longer-Distance Rolling Stock Busines Case - Final.docx Executive Summary Introduction This business case has been prepared by Stantec New Zealand and Greater Wellington Regional Council (GWRC), with input from key stakeholders including KiwiRail, Transdev, Horizons Regional Council and the NZ Transport Agency (NZTA), and economic peer review by Transport Futures Limited. -

Bay of Plenty Region Passenger and Freight Rail FINAL Report May 2019

1 | P a g e Bay of Plenty Passenger and Freight Rail Phase 1 Investigation Report May 2019 Contents Page Contents Page ......................................................................................................................................... 2 1.0 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 2.0 Overall Findings and Future Opportunities ................................................................................. 6 2.1 Overall Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 2.2 Future Opportunities ............................................................................................................ 10 3.0 Bay of Plenty Passenger and Freight Rail Investigation 2019 ................................................... 13 3.1 Phase 1 Investigation ............................................................................................................ 13 3.2 Stakeholders / Partners ........................................................................................................ 13 3.3 New Zealand Transport Agency Business Case Approach .................................................... 14 3.4 Bay of Plenty Rail Strategy 2007 ........................................................................................... 14 4.0 National Strategy and Policy Settings ...................................................................................... -

Document 2 Contributors

DOCUMENT 2 CONTRIBUTORS Architects and Builders: Health: Barnaby Bennett, Architect Northland DHB Harnett Building Tiaho Trust NZ Institute of Building Maoridom: Arts: Elizabeth Ellis and Patu Hohepa Hamish Keith Hihiaua Cultural Centre Trust, Richard Drake Barnaby Weir, Musician Maori Advisory Panel, Elizabeth Ellis Jenny Bennett Group, Artists Te Huinga, Pita Tipene Paul McLaney, Mushroom Music Steve Moase, Artist and Musician Sport: Dianne Swann - Musician Activ8 Business: Northland Football League Sport Northland Advantage Business Northland Andrew Garratt, Human Resources Manager Stats and Surveys: Northland Chamber of Commerce Golden Kiwi Holdings Holiday Park Stats Northland Economic Action Group Legacy of Hundertwasser in Kawakawa Sir Michael Hill Survey report for Cruise NZ Webb Ross Lawyers Te Taitokerau Teachers Survey Whangarei Economic Development Group Latest Media Release Cruise NZ_ 30-09-2014 Whangarei CBD Hospitality Group Photgraphic Parking Survey_C King World of Decor Burning Issues Gallery - Jan Twentyman Tourism: Northland Branch Hospitality NZ Jane Scripps, B&B manager Marsden Woods Inskip Smith - Lawyers Positively Wellington Shorestone - Consultants Sir Bob Harvey Hospitality Northland Top Ten Holiday Park, Kevin and Linda Lloyd Tourism Bay of Plenty Education: Tourism N.Z. Adrian Smith, Principals Association Whangarei Visitors Group Julia Parry, Teacher Tourism Industry Association People Potential Pompellier College students Under 40’s: Whangarei Boys High School Board of Trustees Ben Tomason Group Taleesha -

Report 08-102 Metro Passenger Train Derailment, Sylvia Park, 14 April 2008

Report 08-102 Metro passenger train derailment, Sylvia Park, 14 April 2008 (incorporating inquiries 08-104 and 08-107) Diesel motor fires on board metro passenger trains, 3 June 2008 and 25 July 2008 The Transport Accident Investigation Commission is an independent Crown entity established to determine the circumstances and causes of accidents and incidents with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. Accordingly it is inappropriate that reports should be used to assign fault or blame or determine liability, since neither the investigation nor the reporting process has been undertaken for that purpose. The Commission may make recommendations to improve transport safety. The cost of implementing any recommendation must always be balanced against its benefits. Such analysis is a matter for the regulator and the industry. These reports may be reprinted in whole or in part without charge, providing acknowledgement is made to the Transport Accident Investigation Commission. Final Report Rail Inquiry 08-102 Metro passenger train derailment, Sylvia Park, 14 April 2008 (incorporating inquiries 08-104 and 08-107) Diesel motor fires on board metro passenger trains, 3 June 2008 and 25 July 2008 Approved for publication: August 2011 Transport Accident Investigation Commission About the Transport Accident Investigation Commission The Transport Accident Investigation Commission (Commission) is an independent Crown entity responsible for inquiring into maritime, aviation and rail accidents and incidents for New Zealand, and co-ordinating and co-operating with other accident investigation organisations overseas. The principal purpose of its inquiries is to determine the circumstances and causes of occurrences with a view to avoiding similar occurrences in the future. -

Kaipara North Dairy Factory Source Material: Former Dairy Factory, Whakapirau (((Image Source: Liz Clarkliz Clark 200920092009)))

HISTORIC HERITAGE SITE NRC IDNRC ID 040404 Appendix: Background Information for Kaipara North Dairy Factory Source Material: Former dairy factory, Whakapirau (((image source: Liz ClarkLiz Clark 200920092009))) Source Material: Former dairy factory, WhakapirauWhakapirauWhakapirau. Note originally a wooden jetty structure ran along the face of the building, and has been obscured or demolished and a metalled road made up (((image(image source: Liz ClarkLiz Clark 200820082008)2008))) 1 HISTORIC HERITAGE SITE NRC IDNRC ID 040404 Appendix: Background Information for Kaipara North Dairy Factory Source Material: FFFormer dairy factory, Whakapirau. Note the main roof is apparently of corrugated asbestos/fibrolite type material, and the original louvre vents are absent, indicating the main building may have been reroofed in the past (((image(image source: Liz Clark 200820082008)2008))) Source Material: Former dairy factory, Whakapirau (((image source: Liz ClarkLiz Clark 200820082008))) 2 HISTORIC HERITAGE SITE NRC IDNRC ID 040404 Appendix: Background Information for Kaipara North Dairy Factory Source Material: Former dairy factory, Whakapirau (((image source: Liz ClarkLiz Clark 200920092009))) Source Material: Former dairy factory, Whakapirau (image source: Liz Clark 2009) 3 HISTORIC HERITAGE SITE NRC IDNRC ID 040404 Appendix: Background Information for Kaipara North Dairy Factory Source Material: Former dairy factory, Whakapirau (image source: Lifestyler http://www.kaiparalifestyler.co.nz/Of_Interest.cfm?NewsID=5892, posted 201320132013)2013))) Source Material:Material:Material: Former Dairy Factory Whakapirau, 1904 (source: http://maungaturotomemories.blogspot.co.nz/2010/01/northhttp://maungaturotomemories.blogspot.co.nz/2010/01/north----kaiparakaiparakaiparakaipara----cocococo---- operativeoperativeoperative-operative---dairy.htmldairy.htmldairy.htmldairy.html,, accessed 29/03/206) 4 HISTORIC HERITAGE SITE NRC IDNRC ID 040404 Appendix: Background Information for Kaipara North Dairy Factory Source Material: BlackBlackBlackwell, F B. -

Hearing Transcript Day 21.Pdf

TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS BOARD OF INQUIRY MacKays to Peka Peka Expressway Proposal HEARING at KAPITI COAST on 10 JANUARY 2013 BOARD OF INQUIRY: Sir John Hansen (Chairperson) Environment Commissioner David Bunting (Board Member) Ms Glenice Paine (Board Member) Mr Mark Apeldoorn (Board Member) Page 1897 [9.31 am] CHAIRPERSON: Thank you. Just before we call Mr Gross and Mr Gray, 5 Commissioner Bunting has indicated that he worked in the same organisation as Mr Gray many years ago. He identified that to the Board beforehand and, just for the record, we are satisfied there is no conflict of interest involved. So Mr Gross and Mr Gray if you would come forward please. 10 MR GROSS: Sir John, commissioners, my name is Michael Gross, I am currently chairperson of the Wellington District of the New Zealand Automobile Association. I have a background in local government, I chaired various local, regional and national bodies of local government 15 during the 1980s and 1990s and was spokesman for the New Zealand Local Government Association on transport issues at that time. After I exited local government in 1995 I was the establishment chair of the Transfund board and chaired that organisation for seven of its 20 nine years until policy changes saw it re-amalgamated with the Safety Authority and later, of course, morphed into the New Zealand Transport Agency as we have today. I have with me Mr Alex Gray who is an engineer who has spent a 25 career in major infrastructure projects around the Wellington region and he will largely present our submission. -

Statement on Public Transport for Palmerston North

STATEMENT ON PUBLIC TRANSPORT FOR PALMERSTON NORTH JUNE 2011 About this Strategy The Palmerston North City Council Public Transport Position Statement was prepared in 2011 to assist the Council with formulating its submission on the Horizons Regional Council draft Regional Public Transport Plan (2012 – 2022). The document was adopted by the Palmerston North City Council in June 2011. Credits: Published by Palmerston North City Council Bus photo on page 4 Horizons Regional Council Cover, Design & Layout Print Synergy Capital Connection photo courtesy of KiwiRail CONTENTS SUMMARY 5 BACKGROUND 7 OPTIONS FOR IMPROVING PUBLIC TRANSPORT 9 CAPITAL CONNECTION RAIL SERVICE 11 ECONOMIC IMPLICATIONS 12 PUBLIC TRANSPORT RECOMMENDATIONS 13 FUTURE PUBLIC TRANSPORT? 14 SUMMARY The City Council adopted the The development of an effective public transport system is fundamental to the Council achieving this 5 Sustainable City Strategy in vision. To achieve this aspiration there will need to 2010, which reflects the be a number of changes over time, including: Council’s 2009 – 2019 1. Increasing the frequency long-term plan goal that: of city bus services 2. Extending the hours of [ Summary ] operation of bus services Palmerston North is a leading 3. Improving bus routes city in the quest to become environmentally sustainable. 4. Expanding the Capital Connection rail service 5. Council parking policy supporting public transport 6. Identifying new and innovative ways to ensure public transport is NORTH FOR PALMERSTON affordable for everyone in the city. 7. To ensure joined-up policy and implementation a joint working party between the City Council and Horizons Regional Council is established to investigate possible enhancements to city and regional bus services. -

Nzca 262 Between Opua Coastal Preservation I

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF NEW ZEALAND I TE KŌTI PĪRA O AOTEAROA CA119/2017 [2018] NZCA 262 BETWEEN OPUA COASTAL PRESERVATION INCORPORATED Appellant AND FAR NORTH DISTRICT COUNCIL First Respondent MINISTER OF CONSERVATION Second Respondent D C SCHMUCK Third Respondent Hearing: 13 February 2018 (further submissions received 6 March 2018) Court: Winkelmann, Brown and Gilbert JJ Counsel: T H Bennion and E A Whiley for Appellant JGA Day for First Respondent B R Arapere and WMC Randal for Second Respondent J A Browne and C H Prendergast for Third Respondent Judgment: 20 July 2018 at 11.30 am Reissued: 20 November 2018 Effective date of Judgment: 20 July 2018 JUDGMENT OF THE COURT A The appeal is allowed. B The Minister’s decision of 5 June 2015 to consent to the easements is quashed, save in respect of easements A3 and E. OPUA COASTAL PRESERVATION INCORPORATED v FAR NORTH DISTRICT COUNCIL [2018] NZCA 262 [20 July 2018] C The first and third respondents are jointly and severally liable to pay the appellant one set of costs for a standard appeal on a band A basis and usual disbursements. We certify for two counsel. D Costs in the High Court are remitted back to that Court for determination. ____________________________________________________________________ REASONS OF THE COURT (Given by Winkelmann J) Table of Contents Para No. Introduction [1] Factual background [4] The boatyard business [5] The land becomes an esplanade reserve [12] 1999: First application for easements [15] 2000: Resource management consents [17] 2003–2004: Further applications -

Rock'n'dine and Dance Fishing Limits

JUNE 2016 Fishing limits - Is it Fair? Rock'n'dine and dance A question has been raised. It was on the night The Kauri Museum held Is it fair? Recreational fishing quotas are different on Northland's west coast their fundraising event for Totara House that compared to the east. Is there over-fishing in the Kaipara? Do eastcoasters Matakohe Hall rocked til midnight! While an come over to the Kaipara because they can take more fish per day compared overnight storm raged outside, around 150 locals to what they are permitted on 'their side'? braved cold wind and rain to turn out in force. Accordingly, Paparoa Press spoke with some local recreational fishing people Inside, the canapes, served by The Friends of from around the Kaipara and their comments are recorded here. the Museum and mains and dessert by Country Caterers was superb. Fisherman one Fishermen two & three Once the band got going, the crowd (many Q. How do you feel about Regulations should be of the older generation) soon warmed up the fact that east coast the same everywhere with dancing! Shane and the Shazams (Alister recreational fishermen to prevent confusion. Taylor and his fellow musical old-rockers) had are only allowed to The lower limit is fine everyone twisting, jiving and singing along to all catch seven snapper per and most fishermen the rock'n'roll songs you could imagine. Think person where as Kaipara in the Kaipara self The Beatles, Cliff Richards, Buddy Holly and The fisherman are allowed regulate and actually Rolling Stones. to catch ten? only catch what they A.