The Seven Sins of Thematic Investing Common Implementation Mistakes in Long-Term Equity Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10 for 2020: Creating Impact Through Thematic Investing

10 FOR 2020: CREATING IMPACT THROUGH THEMATIC INVESTING January 2020 Doug Morrow Martin Vezér Director, Manager, Portfolio Research Thematic Research 10 for 2020: Creating impact through thematic investing January 2020 About Sustainalytics Sustainalytics is a leading independent ESG and corporate governance research, ratings and analytics firm that supports investors around the world with the development and implementation of responsible investment strategies. For over 25 years, the firm has been at the forefront of developing high-quality, innovative solutions to meet the evolving needs of global investors. Today, Sustainalytics works with hundreds of the world’s leading asset managers and pension funds who incorporate ESG and corporate governance information and assessments into their investment processes. With 16 offices gloBally, Sustainalytics has more than 600 staff members, including over 200 analysts with varied multidisciplinary expertise across more than 40 industry groups. For more information, visit www.sustainalytics.com. Copyright ©2020 Sustainalytics. All rights reserved. This puBlication contains information developed By Sustainalytics (www.sustainalytics.com), a leading independent ESG and corporate governance research, ratings and analytics firm operating for over 25 years and supporting investors around the world with the development and implementation of responsible investment strategies. The ownership and all intellectual property rights to this puBlication and the information contained herein are vested exclusively in Sustainalytics. The information contained in it may Be used or made availaBle to third parties provided that either it is shared in the form and format disclosed By Sustainalytics or paragraphs and information are quoted unaltered and appropriate citation and acknowledgement is ensured By including reference to the paragraph aBove. -

Thematic Investing for Fund Distributors and Professional Active Is: Investing in the World Ahead Investors Only

Allianz Global Investors Thematic Investing For fund distributors and professional Active is: Investing in the world ahead investors only THEMATIC INVESTING: BE PART OF THE STORY In the days of millennials inheriting the convictions and want to identify longer- Earth and information at the swipe of our term growth opportunities. Typically, fingers, many investors are uninspired by themes are well-known, starting as topics plain vanilla investment products. People of conversation among budget decision want more out of their investments, and makers within companies, and will later this isn’t limited to the size of the return become visible in most people’s personal – it includes the ability to invest in the experience. areas of the economy that are of personal Andreas Fruschki Portfolio Manager interest to them – and moreover for their Themes are best characterised as powerful money to be aligned with their personal and secular shifts, triggered by innovation views of the world. They want to be part or regulation, a narrowing supply-demand of the story. situation or socio-economic factors. Thematic funds aim to identify the winning How is thematic investing themes impacted by these shifts and to allow investors to participate in them. They different? permit anyone who has a view on a theme Thematic funds serve the large market of to take it forward with an investment. investors who have forward-looking Figure 1: Four megatrends rbanisation Technological Resource emographic Innovation Scarcity Social Change Source: Allianz Global Investors. This is for illustrative purposes only. Value. Shared. A key benefit of thematic investing is the structural shifts (megatrends). -

Outcome-Oriented Thematic Investing

T R A N S C R I P T Outcome-oriented thematic investing Chris Peixotto: All right, thanks. And hi, everyone. So my name is Chris Peixotto and I work in our investment product group here at Fidelity. We’re really excited to have Pranay and Zach on the call today. Pranay is the portfolio manager of our Fidelity Infrastructure Fund and Zach is the portfolio manager of our new Fidelity US Low Volatility Equity Fund. But before we turn things to them and have them talk more about their funds and approaches, wanted to just provide some quick background on what is thematic investing and how does outcome-oriented thematic investing fit in. So if we go to slide three to start here, we’ll start with so what is thematic investing. Thematic is really an investment approach that allows you to invest in long-term trends and themes that really align with something that you believe in and with your objective. It tends to be a newer investment approach and really differs from traditional investment frameworks. So some traditional frameworks might be like regional investing, thinking about US versus emerging market exposure, style box investing, thinking about say large-caps versus small-cap stocks, sector investing, thinking about something like the energy sector versus the health care sector. Thematic investing tends 1 to cut across these traditional frameworks to really align with a given idea or opportunity or in this case a specific outcome. As a newer category, we’ve been trying to publish insights and research to really help investors think about thematic investing, understand what it is, and help to think about the role in a portfolio. -

Thematic Investing in the Time of Coronavirus

Thematic Investing In the Time of Coronavirus MASH0321E/S-1544658-1/7 Summary The Coronavirus pandemic has ushered in countless changes in the way we live our daily lives. From an investment perspective, we seek to Adam Ryan generate performance for our clients by gaining targeted exposure to Portfolio Manager and Head of these changes by looking beyond traditional asset class and sector Diversified Strategies, Multi-Asset Strategies & Solutions lenses. We often do this by constructing “baskets” of securities which we have selected to benefit from a particular theme. We see opportunities to capitalise on macroeconomic and microeconomic dislocations through thematic investing over both tactical and strategic time horizons. Capital at risk: The value of investments and the income from them Yasmin Meissner can fall as well as rise and are not guaranteed. Co-Head of Sustainable Investing, Multi Asset Strategies & Solutions Tactical The back-and-forth between lockdown measures taken by governments to reduce the spread of the virus and the easing of those restrictions have been rightly qualified as waves. Such cycles create opportunities for tactical and dynamic investment strategies: • Example 1. New behaviours predominantly observed as a product Arjun Kapur of the first wave of lockdowns Investment Strategist, BlackRock Investment Institute • Example 2. Bounce-back effects resulting from the reopening of economies as vaccines are rolled out Strategic Beyond these short-term cycles, we note that there are longer-term macroeconomic impacts associated with the pandemic, and posit that key trends exacerbated by the pandemic are here to stay. Helene Procoudine-Gorsky We point specifically to a growing consciousness of risk associated Researcher, Multi Asset Strategies & Solutions with climate change and an environment in which fiscal policy plays a determinant role in shaping the recovery and the green transition— both of which reinforce pre-existing ESG momentum. -

Thematic Investing: a Systematic Approach to Finding Disruptive Trends by Ing-Chea Ang April 2021

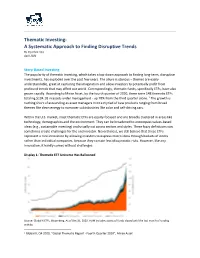

_____________________________________________________________________________________ Thematic Investing: A Systematic Approach to Finding Disruptive Trends By Ing-Chea Ang April 2021 Story-Based Investing The popularity of thematic investing, which takes a top-down approach to finding long-term, disruptive investments, has exploded over the past few years. The allure is obvious – themes are easily understandable, great at capturing the imagination and allow investors to potentially profit from profound trends that may affect our world. Correspondingly, thematic funds, specifically ETFs, have also grown rapidly. According to Mirae Asset, by the fourth quarter of 2020, there were 148 thematic ETFs totaling $104.1B in assets under management - up 78% from the third quarter alone. 1 The growth is nothing short of astounding as asset managers mint a myriad of new products ranging from broad themes like clean energy to narrower subindustries like solar and self-driving cars. Within the U.S. market, most thematic ETFs are equity-focused and are broadly clustered in areas like technology, demographics and the environment. They can be broadened to encompass values-based ideas (e.g., sustainable investing) and usually cut across sectors and styles. These fuzzy definitions can sometimes create challenges for the end investor. Nevertheless, we still believe that these ETFs represent a nice innovation by allowing investors to express macro ideas through baskets of stocks rather than individual companies, because they contain less idiosyncratic risks. However, like any innovation, it hardly comes without challenges. Display 1: Thematic ETF Universe Has Ballooned Source: Global X ETFs, Bloomberg. As of Dec 31, 2020. AUM includes assets of funds closed until the last month of trading activity 1 Global X, Q4 2020, “Global Thematic Report - Fourth Quarter 2020”, Mirae Asset _____________________________________________________________________________________ Deceptively Easy, but Challenges Abound Reaping the rich rewards of thematic investing, however, is easier said than done. -

Thematic Investing

Thematic Investing Transforming World: The 2020s Thematic Investing 11 November 2019 The Decade of Inflection: reaching boiling point We enter the next decade with interest rates at 5,000-year lows, the largest asset bubble in history, a planet that is heating up, and a deflationary profile of debt, disruption and demographics. We will end it with nearly 1bn people added to t h e world, a Equity rapidly ageing population, up to 800mn people facing the threat of job automation and Global the environment on the brink of catastrophic change. At the same time, 3bn more Thematic Investing people will be connected online and global data knowledge will be 32x greater than today. The social, political and economic responses to these challenges, all heading to a boiling point this decade, will overhaul traditional paradigms. We outline BofAML Transforming World’s top 10 themes to help investors navigate this decade ahead. 10 Themes for the Next 10 Years 1) Peak Globalization: the end of unrestricted free movement of labor, goods, and capital around the world. Winners: local markets, real assets; Losers: global markets. 2) Recession: record numbers of FMS investors think the global economy is late-cycle, the bond market bubble is set to unwind and populism is likely to be inflationary. Winners: inflation, real assets, infrastructure; Losers: growth, credit, deflation. 3) Quantitative Failure: monetary policy measures are proving less and less effective Haim Israel >> at boosting corporate and household “animal spirits”. Winners: Keynesianism, gold; Equity Strategist Losers: financial assets, Monetarism. Merrill Lynch (Israel) [email protected] Michael Hartnett 4) Demographics: the number of grandparents will outnumber the world’s children; Chief Investment Strategist every second 5 people enter the EM middle class and Gen Z overtakes Millennials. -

Thematic Investing OK Zoomer: Gen Z Primer

Thematic Investing OK Zoomer: Gen Z Primer Thematic Investing This is a redaction of a report originally published on November 10, 2020. 01 December 2020 Equity Here come the Zillennials! Gen Y is out, Gen Z is in Global They’ve never known a life without Google, 40% prefer hanging out with friends virtually than in real life, they will spend six years of their life on social media and they won’t use credit cards. They’re the ‘clicktivists’: flourishing in a decade of social rights movements, with 4 in 10 in our proprietary BofA survey seeing themselves as ‘citizens of the world'. The Gen Z revolution is starting, as the first generation born into an online world is now entering the workforce and compelling other generations to adapt to them, not vice versa. Thus, about to become most disruptive to economies, markets and social systems. $33tn income by 2030, to pass Millennials by 2031 Gen Z’s economic power is the fastest-growing across all cohorts. This generation’s income will increase c.5x by 2030 to $33tn as they enter the workplace today, reaching 27% of global income and surpassing Millennials the year after. The growing consumer power of Gen Z will be even more powerful taking into account the Great Wealth ‘ Haim Israel >> Transfer’ down the generations. The Baby Boomer and Silent generation US households Equity Strategist Merrill Lynch (Israel) alone are sitting on $78tn of wealth today. Lauma Kalns-Timans >> Equity Strategist 9 in 10 live in EM, while DM suffers from “peak youth” MLI (UK) Gen Z could be EM’s secret weapon. -

Responsible Or Thematic? the True Nature of Sustainability-Themed Mutual Funds

sustainability Article Responsible or Thematic? The True Nature of Sustainability-Themed Mutual Funds Federica Ielasi 1,* and Monica Rossolini 2 1 Department of Economics and Management, University of Florence, 50127 Florence, Italy 2 Department of Business and Law, University of Milano-Bicocca, 20126 Milan, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: federica.ielasi@unifi.it; Tel.: +39-339-8510987 Received: 30 April 2019; Accepted: 10 June 2019; Published: 15 June 2019 Abstract: The aim of the paper is to compare the risk-adjusted performance of sustainability-themed funds with other categories of mutual funds: sustainable and responsible mutual funds that implement different approaches in portfolio selection and management, and thematic funds not committed to responsible investments. The study analyses a sample of about 1000 European mutual open-end funds where 302 are sustainability-themed funds, 358 are other responsible funds, and 341 other thematic funds. Risk-adjusted performance is analyzed for the period 2007–2017 using different methodologies: a single factor Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), a Fama and French (1993) 3-factor model, and a Fama and French (2015) 5-factor model. Our main findings demonstrate that the risk-adjusted performance of ST funds is more closely related to their responsible nature than to their thematic approach. Sustainability-themed mutual funds are more similar to other socially responsible funds than to other thematic funds, as confirmed by performance analysis over time. They are also better than other thematic funds in overcoming financially turbulent periods and currently benefit from SRI regulation and disclosure. Keywords: fund managers; mutual fund; ESG investing; socially responsible funds; thematic funds; sustainability-themed funds 1. -

Thematic Investing Generation Next

Thematic Investing Generation Next - Millennials Primer Primer Equity | 08 July 2015 Global Key takeaways Thematic Investing • Millennials: 2bn aged 18-34Y globally, emerging as #1 source of global income, wealth & spending Sarbjit Nahal >> Equity Strategist • 8 entry points: 1) Tech; 2) Consumers; 3) Food & Drink; 4) Education; 5) Housing; MLI (UK) 6) Financials; 7) Women; 8) Sharing Economy Beijia Ma >> Equity Strategist A Transforming World: Millennials MLI (UK) As part of our work on A Transforming World, we introduce a new people-focused theme in this Primer and a Primer Picks report; we set out the challenges and opportunities offered by Felix Tran >> the Millennials theme. Equity Strategist MLI (UK) Millennials: #1 global and US demographic We define Millennials (aka “Generation Y”) as the demographic cohort born post-1980 (aged 18-34Y). Globally, there are c.2bn Millennials, with 86% living in EMs. In the US, Millennials A Transforming World (c.75mn) are set to overtake the Baby Boomers in 2015 as the largest living generation. While the US Boomer demographic is ageing and shrinking in size (cf. our Silver Dollar report), the Millennials generation continues to grow, driven by immigration, peaking in the US only in 2036E at 81.1mn. #1 income & wealth: $8.3tn by 2025E in the US alone While the Boomers have accumulated wealth and currently lead consumer spending, Millennials are emerging as the new dominant source of both. They are the #1 workforce demographic in the US and account for $1.3tn in direct annual consumer spending, which will grow as their annual income reaches $8.3tn by 2025E in the US alone. -

Thematic Investing

FINANCIAL STANDARD GUIDE TO THEMATIC INVESTING GUIDE SERIES 5 PROUDLY SUPPORTED BY PUBLISHED BY a Rainmaker Information company 01 Cover_Thematic Investing.indd1 1 25/6/09 10:04:26 AM Life Insurance Life Insurance Investments Investments General Insurancence General Insurancence Count emerging trends The more baskets, the safer your eggs before they hatch Improve investment returns by identifying trends early Reduce risk by investing in The key to successful thematic investing is identifying a number of themes trends early and knowing which trends present the best It is possible to achieve long-term out-performance with less risk investment opportunities. Investors in the Zurich Investments than the market by investing in a number of themes that each focus on Global Thematic Share Fund, managed by our strategic investment different investment opportunities. Investors in the Zurich Investments partner Lazard Asset Management, benefit from over 22 years of Global Thematic Share Fund, managed by our strategic investment thematic investment experience and a truly global perspective. partner Lazard Asset Management, benefit from diversification across To learn more, call 1800 004 480 or visit www.zurich.com.au 8–12 themes. To learn more, call 1800 004 480 or visit www.zurich.com.au Here to help your world Here to help your world Zurich Investment Management Limited ABN 56 063 278 400 AFSL 232511 5 Blue St. North Sydney, 2060 (‘Zurich Investments’) is the issuer of the Zurich Investments Zurich Investment Management Limited ABN 56 063 278 400 AFSL 232511 5 Blue St. North Sydney, 2060 (‘Zurich Investments’) is the issuer of the Zurich Investments Global Thematic Share Fund (the ‘Fund’). -

Thematic Investing: What Is It, and How Should Investors Think About It?

Insights Thematic Investing: What Is It, and How Should Investors Think About It? Chris Peixotto, CFA KEY TAKEAWAYS Vice President, Investment Product • Thematic investing allows investors to pursue market exposure to specific ideas or values. Jordan Alexiev, CFA • Fidelity has identified five different types of thematic investing, each with a Portfolio Manager, different overall approach. Global Insitutional Solutions • Within each type, there may be different strategies for reflecting the theme, Sarah Pulsifer, CFA including different approaches to selecting investments. Vice President, Investment Product • Thematic mutual funds and exchange traded funds (ETFs) may provide focused exposure to a theme plus the benefits of professional research and management. Risteard Hogan Chief Investment Officer Introduction “Thematic investing” refers to strategies through which investors can invest in long- term ideas and trends, allowing them to capture potential opportunities created by the impact of economic, technological, and social changes. Approaches based on themes can help investors “personalize” their portfolios to include more investments that align with their focused interests or expectations. It differs from more traditional approaches, such as investing by region (U.S. stocks), market capitalization (small cap), style (growth stocks), or economic sector (consumer discretionary). Instead, thematic investing allows investors to express a view that may cut across market capitalization, sector classification, and region. Although investors often approach thematic investing through stocks, it can include other asset classes (such as bonds or real assets) as well. Thematic investing has been increasing in popularity. Mutual funds and ETFs focused on style, region, sector, or industry exposures still hold the majority of assets, whether those approaches are broad or more specific. -

Thematic Investing

THEMATIC Harnessing the power INVESTING of global megatrends An unconstrained equity fund Investing in global equities using a thematic approach is very different from traditional investment styles. The managers of John Hancock Global Thematic Opportunities Fund identify themes underpinned by secular megatrends set to structurally change the way we live, how society operates, and how business gets done. Stocks representing different themes are selected based on how well the managers believe they’re positioned for the future as it’s redefined by these deep structural changes. Megatrends play out over decades Megatrends are powerful forces that are transforming the future of our world and the global investment landscape. They range from technological paradigm shifts like the network economy to long-term changes in global demographics. High impact Megatrends Trends Microtrends Temporary phenomena 15 years+ Megatrends we’ve identified Pictet currently has identified 14 megatrends, each of which we believe will drive future investment opportunities. The increasing connectedness of business processes and economic activity, enabling the Network economy transfer of knowledge and goods directly from provider to receiver The ability to meet current needs without compromising the ability of future generations to Sustainability meet theirs Knowledge is becoming an economic resource in the way raw materials, labor, and capital Knowledge society have traditionally been as society transitions from the industrial age to the information age Consumers are