Pediatric Episodic Migraine with Aura: a Unique Entity?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visual Perception in Migraine: a Narrative Review

vision Review Visual Perception in Migraine: A Narrative Review Nouchine Hadjikhani 1,2,* and Maurice Vincent 3 1 Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02129, USA 2 Gillberg Neuropsychiatry Centre, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, 41119 Gothenburg, Sweden 3 Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN 46285, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-617-724-5625 Abstract: Migraine, the most frequent neurological ailment, affects visual processing during and between attacks. Most visual disturbances associated with migraine can be explained by increased neural hyperexcitability, as suggested by clinical, physiological and neuroimaging evidence. Here, we review how simple (e.g., patterns, color) visual functions can be affected in patients with migraine, describe the different complex manifestations of the so-called Alice in Wonderland Syndrome, and discuss how visual stimuli can trigger migraine attacks. We also reinforce the importance of a thorough, proactive examination of visual function in people with migraine. Keywords: migraine aura; vision; Alice in Wonderland Syndrome 1. Introduction Vision consumes a substantial portion of brain processing in humans. Migraine, the most frequent neurological ailment, affects vision more than any other cerebral function, both during and between attacks. Visual experiences in patients with migraine vary vastly in nature, extent and intensity, suggesting that migraine affects the central nervous system (CNS) anatomically and functionally in many different ways, thereby disrupting Citation: Hadjikhani, N.; Vincent, M. several components of visual processing. Migraine visual symptoms are simple (positive or Visual Perception in Migraine: A Narrative Review. Vision 2021, 5, 20. negative), or complex, which involve larger and more elaborate vision disturbances, such https://doi.org/10.3390/vision5020020 as the perception of fortification spectra and other illusions [1]. -

Migraine: Spectrum of Symptoms and Diagnosis

KEY POINT: MIGRAINE: SPECTRUM A Most patients develop migraine in the first 3 OF SYMPTOMS decades of life, some in the AND DIAGNOSIS fourth and even the fifth decade. William B. Young, Stephen D. Silberstein ABSTRACT The migraine attack can be divided into four phases. Premonitory phenomena occur hours to days before headache onset and consist of psychological, neuro- logical, or general symptoms. The migraine aura is comprised of focal neurological phenomena that precede or accompany an attack. Visual and sensory auras are the most common. The migraine headache is typically unilateral, throbbing, and aggravated by routine physical activity. Cutaneous allodynia develops during un- treated migraine in 60% to 75% of cases. Migraine attacks can be accompanied by other associated symptoms, including nausea and vomiting, gastroparesis, di- arrhea, photophobia, phonophobia, osmophobia, lightheadedness and vertigo, and constitutional, mood, and mental changes. Differential diagnoses include cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoenphalopathy (CADASIL), pseudomigraine with lymphocytic pleocytosis, ophthalmoplegic mi- graine, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome, mitochondrial disorders, encephalitis, ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, and benign idiopathic thunderclap headache. Migraine is a common episodic head- (Headache Classification Subcommittee, ache disorder with a 1-year prevalence 2004): of approximately 18% in women, 6% inmen,and4%inchildren.Attacks Recurrent attacks of headache, consist of various combinations of widely varied in intensity, fre- headache and neurological, gastrointes- quency, and duration. The attacks tinal, and autonomic symptoms. Most are commonly unilateral in onset; patients develop migraine in the first are usually associated with an- 67 3 decades of life, some in the fourth orexia and sometimes with nausea and even the fifth decade. -

A Review on Migraine

Acta Scientific Pharmaceutical Sciences (ISSN: 2581-5423) Volume 3 Issue 1 January 2019 Review Article A Review on Migraine Poojitha Mamindla1*, Sharanya Mogilicherla1, Deepthi Enumula1, Om Prakash Prasad2 and Shyam Sunder Anchuri1 1Department of Pharm-D, Balaji Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Laknepally, Narsampet, Warangal, Telangana, India 2Sri Sri Neurocentre, Hanamkonda, Warangal, Telangana, India *Corresponding Author: Poojitha Mamindla, Department of Pharm-D, Balaji Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Laknepally, Narsampet, Warangal, Telangana, India. Received: November 02, 2018; Published: December 06, 2018 Abstract Headache disorders, characterized by recurrent headache, are among the most common disorders of the nervous system. Mi- graine, the second most common cause of headache and indeed neurologic cause of disability in the world and attacks lasting 4-72 hours, of a pulsating quality, moderate or severe intensity aggravated by routine physical activity and associated with nausea, vomit- ing, photophobia or phonophobia. Migraine has multiple phases: premonitory, aura, headache, postdrome, and interictal. The pri- mary cause of a migraine attack is unknown but probably lies within the central nervous system. Migraine can occur due to various triggering factors and can be managed with both pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment. Migraine attacks are treated therapy, Complementary Treatments, yoga therapy etc. with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), or triptans. Non-pharmacological treatment includes cognitive behavioural Keywords: Migraine; NSAIDS; Therapy Introduction Migraine is a common chronic headache disorder which is char- acterized by the recurrent attacks which lasts from 4-72 hours, Headache disorders, this are characterized by the recurrent with a pulsating quality. Migraine is the commonest cause of head- episodes of headache and are the most common nervous system ache and its intensity includes as mild, moderate and severe, it is disorders. -

The Woman Who Saw the Light R

Cases That Test Your Skills The woman who saw the light R. Andrew Sewell, MD, Megan S. Moore, MD, Bruce H. Price, MD, Evan Murray, MD, Alan Schiller, PhD, and Miles G. Cunningham, MD, PhD How would you Since her first psychotic break 7 years ago, Ms. G sees dancing handle this case? lights and splotches continuously. What could be causing her Visit CurrentPsychiatry.com to input your answers visual hallucinations? and see how your colleagues responded HISTORY Visual disturbances history of migraines. Ms. G has a history of ex- Ms. G, age 30, has schizoaffective disorder and periencing well-formed visual hallucinations, presents with worsening auditory hallucina- such as the devil, but has not had them for tions, paranoid delusions, and thought broad- several years. casting and insertion, which is suspected to be She had 5 to 10 episodes over the last 2 related to a change from olanzapine to aripip- years that she describes as seizures—“an razole. She complains of visual disturbances— earthquake, a huge whooshing noise,” accom- a hallucination of flashing lights—that she panied by heart palpitations that occur with describes as occurring “all the time, like salt- stress, in public, in bright lights, or whenever and-pepper dancing, and sometimes splotch- she feels vulnerable. These episodes are not es.” Her visual symptoms are worse when she associated with loss of consciousness, incon- closes her eyes and in dimly lit environments, tinence, amnesia, or post-ictal confusion and but occur in daylight as well. Her vision is oth- she can stop them with relaxation techniques erwise unimpaired. -

Headache Medicine: a Crossroads of Otolaryngology, Ophthalmology, and Neurology

FEATURE STORY NEURO-OPHTHALMOLOGY Headache Medicine: a Crossroads of Otolaryngology, Ophthalmology, and Neurology Numerous symptoms can suggest both ophthalmological and neurological disorders. BY PAUL G. MATHEW, MD, FAHS rimary headaches are a set of complex pain disor- part of the diagnostic criteria for migraine, in a study of ders that can have a heterogeneous presentation. 786 migraine patients (625 women, 61 men), 56% of the Some of these presentations can often involve subjects experienced autonomic symptoms, but these symptoms that suggest otolaryngological and symptoms tended to be bilateral.2 Pophthalmological diagnoses. In this second installment In addition to pain around the orbit, migraines can of a two-part series, the symptoms and diagnoses that also commonly involve blurry vision,3 which tends to overlap between ophthalmology and neurology will be occur during the headache phase of the migraine and addressed (please see the March 2014 issue of Cataract increases as the intensity of the pain peaks. Blurry vision & Refractive Surgery Today for the otolaryngology install- should not be confused with migraine visual aura. Visual ment of this series). The two main complaints that auras by definition are fully reversible, homonymous patients present with for ophthalmology consultations visual symptoms that can involve positive features are eye pain and visual disturbances. When ophthalmo- (scintillating scotomas, fortification spectrum) and/or logical evaluations including slit-lamp examinations and negative features (areas of visual loss). Visual auras typi- tonometry are unremarkable, other diagnostic possibili- cally last from 5 to 60 minutes and can be accompanied ties should be considered. by other aura phenomena in succession such as sensory or speech disturbances.1 A major misconception about MIGRAINE AND CLUSTER HEADACHE migraine aura is that it must occur prior to the onset The numerous causes of eye pain include blepharitis, of the headache. -

Basilar Migraines and Retinal Migraines

P1: KWW/KKL P2: KWW/HCN QC: KWW/FLX T1: KWW GRBT050-62 Olesen- 2057G GRBT050-Olesen-v6.cls August 3, 2005 19:44 ••Chapter 62 ◗ Basilar Migraines and Retinal Migraines Marcelo Bigal and K. Michael A. Welsh Although the second edition of the International Classifica- graine is a symptom profile that suggests posterior fossa in- tion of Headache Disorders (1), preserved the basic classi- volvement. fication of migraine without aura, the classification of mi- Basilar-type migraine was first brought to attention by graine with aura and it subtypes, as well as rarer forms of Bickerstaff (6), after seeing a teenager whose aura symp- migraine, were considerably restructured. Given the range toms were long lasting, bilateral, and very prominent. of disorders that present with features of migraine, a sys- Shortly after, the same clinician saw an elderly man, with tematic approach to the less common disorders that are aura symptoms that rapidly progressed into coma and part of the migraine spectrum is essential to good clini- death. Autopsy showed thrombosis in the basilar artery. cal management and to research (2,3). In this chapter we After collecting data on 34 patients, Bickerstaff postulated review two of these headaches, basilar-type migraine, a that “some prodromal symptoms ... are not in the ter- migraine with aura subtype, and retinal migraine, a rarer ritory of the internal carotid, but of the basilar artery. form of migraine. The premonitory symptoms are different and reflect brain- stem dysfunction. Symptoms consist of bilateral loss or disturbance of vision, ataxia, dysarthria, vertigo, tinnitus, BASILAR-TYPE MIGRAINE and bilateral peripheral dysesthesias, followed by occipi- tal headache. -

Ÿþp R E F a C

9 Preface The present document represents a major effort. The work has been going on for almost three years, and has involved not only the committee members, but also the many members of the 12 subcommittees. The work in the committee and subcom- mittees has been open, so that all interim documents have been available to any- body expressing an interest. We have had a two-day meeting on headache classifi- cation in March 1987 open to everybody interested. At the end of the Third Interna- tional Headache Congress in Florence September 1987 we had a public meeting where the classification was presented and discussed. A final public meeting was held in San Diego, USA. February 20 and 21,1988 as a combined working session for the committee and the audience. Despite all effort, mistakes have inevitably been made. They will appear, when the classification is being used and will have to be corrected in future editions. It should also be pointed out that many parts of the document are based on the ex- perience of the experts of the committees in the absence of sufficient published evi- dence. It is expected however that the existence of the operational diagnostic criteria published in this book will generate increased nosographic and epidemio- logic research activity in the years to come. We ask all scientists who study headache to take an active part in the testing and further development of the classification. Please send opinions, arguments and reprints to the chairman of the classification committee. It is planned to publish the second edition of the classification in 1993. -

Current Perspective on Retinal Migraine

vision Review Current Perspective on Retinal Migraine Yu Jeat Chong 1, Susan P. Mollan 1 , Abison Logeswaran 2, Alexandra B. Sinclair 3,4 and Benjamin R. Wakerley 3,4,* 1 Birmingham Neuro-Ophthalmology, Ophthalmology Department, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham B15 2TH, UK; [email protected] (Y.J.C.); [email protected] (S.P.M.) 2 Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London EC1V 2PD, UK; [email protected] 3 Department of Neurology, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham B15 2TH, UK; [email protected] 4 Metabolic Neurology Group, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Retinal migraine was first formally described in 1882. Various terms such as “ocular migraine” and “ophthalmic migraine” have since been used interchangeably in the literature. The lack of a consistent consensus-based definition has led to controversy and potential confusion for clinicians and patients. Retinal migraine as defined by the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) has been found to be rare. The latest ICHD defined retinal migraine as ‘repeated attacks of monocular visual disturbance, including scintillation, scotoma or blindness, associated with migraine headache’, which are fully reversible. Retinal migraine should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion, which requires other causes of transient monocular visual loss to be excluded. The aim of this narrative review is to summarize the literature on retinal migraine, including: epidemiology and risk factors; proposed aetiology; clinical presentation; and management strategies. It is potentially a misnomer as its proposed aetiology is different from our current understanding of the mechanism of migraine Keywords: retinal migraine; ocular migraine; ophthalmic migraine; migraine aura Citation: Chong, Y.J.; Mollan, S.P.; Logeswaran, A.; Sinclair, A.B.; Wakerley, B.R. -

Complicated Migraines Alyssa E

Complicated Migraines Alyssa E. Blumenfeld, MS,* M. Cristina Victorio, MD,† and Frank R. Berenson, MD‡ Migraines are a common paroxysmal disorder that may present with a multitude of neurologic symptoms. Migraines have been re-categorized in the most recent edition of the International Classification of Headache Disorders. In this article, we review the literature on hemiplegic migraines, alternating hemiplegia of childhood, migraine with brainstem aura, retinal migraine, ophthalmoplegic migraine, Alice in Wonderland syndrome, and acute confusional migraine. We also discuss the principal clinical features, diagnostic criteria, and treatment options for these disorders. Semin Pediatr Neurol 23:18-22 C 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Introduction Hemiplegic Migraine The International Classification of Headache Disorders ICHD 3β defines hemiplegic migraine as a form of (ICHD) is the progressively changing classification system migraine with aura that includes motor weakness. This of headache disorders, which physicians use to properly diagnosis is made when the aura consists of fully diagnose headache conditions. Complicated migraine, reversible motor weakness and visual, sensory, and now classified by ICHD third edition (beta version) speech or language symptoms.2 Hemiplegic migraine is (ICHD 3β) as migraine with aura, is an imprecise term classified as its own migraine sub form because patients used to define types of migraine, which present with with this condition present with differences in genetic and significant neurologic deficits -

Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion in Retinal

perim Ex en l & ta a l ic O p in l h t Cisiecki et al., J Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2019, 10:4 C h f a Journal of Clinical & Experimental o l m l a o n l o r g u y o J Ophthalmology ISSN: 2155-9570 Case Report Open Access Branch Retinal Artery Occlusion in Retinal Migraine: A Case Report Slawomir Cisiecki1,2, Karolina Boninska1,2* and Maciej Bednarski1,2 1Dr K Jonscher Municipal Medical Centre, Lodz, Poland 2Medical Center “Julianow”, Sowinskiego 46, Lodz, Poland *Corresponding author: Karolina Boninska, Medical Center “Julianow”, Sowinskiego 46, Lodz, Poland, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: July 17, 2019; Accepted date: July 30, 2019; Published date: August 6, 2019 Copyright: © 2019 Cisiecki S, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Permanent consequences of retinal migraine are rare. We present a case of branch retinal artery occlusion (BRAO) in the course of ocular migraine in a 29-year old woman. Scotoma; in the visual field persist in 6-month follow-up. During the time of observation, visual acuity in the affected left eye remained 5/8.0 (0.1 logMAR). After being diagnosed with migraine, the patient in this case remains under neurological and ophthalmologic care. Keywords: Branch retinal artery occlusion, Retinal migraine; Another examination performed in this case was automated Scotoma perimetry, conducted with the Frey AP-300 perimeter. -

Visual Migraines to Be Worried About Visual Migraines to Be Worried About

Dr Jo-Anne Pon Consultant Ophthalmologist and Oculoplastic Surgeon Southern Eye Specialists Christchurch 12:15 - 12:30 Visual Migraines to be Worried About Visual Migraines To Be Worried About Jo-Anne Pon Ophthalmologist Mr CS (57yo) • Right visual field loss RE only • Headaches – Like looking through water – Gets them intermittently (yrs) – Shimmering – Not severe – Lasted 60mins – No assoc nausea or need to lie down – Associated with headache – Assoc with tiredness • Started day before visual symptoms • lasted 48hrs • General ache/tension – Visual sx’s resolved • No further episodes • No history of migraine Mr CS • Normal ocular examination Management? • Neuro-imaging? • HVF 30-2 - normal • No investigations • Didn’t return with symptoms Outline • Visual Migraine symptoms – Typical – Red flags/ who needs neuro-imaging • Patterns of transient vision loss Perspective • Migraine with visual symptoms - • Which ones to worry about? common • Very few • Lifetime prevalence in general population 18% • Moorfields/St Thomas study – over 23 years, 9 cases • 1-3% of general population or – Literature 31 cases 1/3 of migraineurs will present 1950 to 2009 (59yrs) c/o visual aura International Classification of Headache Disorders – 3 (ICHD-3) • Prodromal phase • Aura • Headache • Postdromal phase Typical visual aura of migraine Biphasic aura 1. Positive visual phenomenon • Fortification spectra (Teichopsia) • Scintillations (flashing lights) • C-shape or semicircle surrounding scotoma 2. Negative symptoms minutes later • Blank scotoma • Hemianopia -

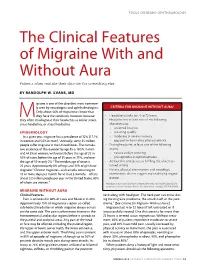

The Clinical Features of Migraine with and Without Aura Patients Often Mistake Their Disorder for Something Else

FOCUS ON NEURO-OPHTHALMOLOGY The Clinical Features of Migraine With and Without Aura Patients often mistake their disorder for something else. BY RANDOLPH W. EVANS, MD igraine is one of the disorders most common- ly seen by neurologists and ophthalmologists. CRITERIA FOR MIGRAINE WITHOUT AURAa Only about 56% of migraineurs know that they have the condition, however, because • Headache attacks last 4 to 72 hours. Mthey often misdiagnose their headaches as ocular strain, • Headache has at least two of the following sinus headaches, or stress headaches. characteristics: • unilateral location EPIDEMIOLOGY • pulsating quality In a given year, migraine has a prevalence of 12% (17.1% • moderate or severe intensity in women and 5.6% in men).1 Annually, some 35 million • aggravation by routine physical activity people suffer migraine in the United States. The cumula- • During headache, at least one of the following tive incidence of this disorder by age 85 is 18.5% in men occurs: and 44.3% in women, with onset before the age of 25 in • nausea and/or vomiting 50% of cases, before the age of 35 years in 75%, and over • photophobia and phonophobia the age of 50 in only 2%.2 The median age of onset is • At least five attacks occur fulfilling the aforemen- 25 years. Approximately 8% of boys and 11% of girls have tioned criteria. migraine.3 Chronic migraine—with attacks occurring on • History, physical examination, and neurologic 15 or more days per month for at least 3 months—affects examination do not suggest any underlying organic about 3.2 million people per year in the United States, 80% disease.