Stanford University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

December 2016 Martin Ruef Curriculum Vitae 344 Soc / Psych Building Office Phone: (919) 660-5792 Duke University Office Fax: (919) 660-5623 Durham, NC 27708-0088 EM: [email protected] EDUCATION: January 1999 Ph.D., Sociology Stanford University June 1994 M.A., Sociology Stanford University May 1990 B.S., Computer Science (Magna Cum Laude) Virginia Tech POSITIONS: 2012-present Jack and Pamela Egan Professor of Entrepreneurship (2013-), Chair (2016-) and Research Professor (2012), Department of Sociology, Duke University 2013-2016 Director (2014-16) and Associate Director (2013-14), Markets and Management Studies, Duke University 2004-2012 Professor (2009-12) and Associate Professor (2004-09), Department of Sociology, Princeton University 2002-2004 Assistant Professor of Organizational Behavior, Graduate School of Business, Stanford University 1999-2002 Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, UNC-Chapel Hill 1998-1999 Postdoctoral Research Scholar, Center for Entrepreneurial Studies, Graduate School of Business, Stanford 1995-1997 Instructor, Department of Sociology, Stanford RESEARCH INTERESTS: Organization Studies, Economic Sociology, Historical / Comparative Sociology, Network Analysis, Sociology of Culture Martin Ruef 2 Curriculum Vitae BOOKS: 2014 Martin Ruef. Between Slavery and Capitalism: The Legacy of Emancipation in the American South. 304pp. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Winner of the 2015 Viviana Zelizer Award (American Sociological Association, Section on Economic Sociology). 2010 Martin Ruef. The Entrepreneurial Group: Social Identities, Relations, and Collective Action. 312pp. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press (paperback edition, 2014). Winner of the 2011 Max Weber Award (American Sociological Association, Section on Organizations, Occupations and Work); Finalist for the 2011 George Terry Award for outstanding contribution to management knowledge (Academy of Management). -

Andrea Cuadra

Andrea Cuadra Department of Information Science Phone: +1 (786) 239 2893 Cornell Tech Email: [email protected] 2 W Loop Rd New York, NY Education † Indicates expected 2018–2022 † Ph.D., Information Science, Cornell University Advisors: Deborah Estrin (chair), Nicola Dell (co-chair), Malte Jung (minor member), Amon Millner (external member) Dissertation title: Inclusive Interaction Design with a focus on Voice Assis- tants for Older Adults 2018–2020 M.Sc., Information Science, Cornell University 2015–2017 M.Sc., Engineering: Product Design, Stanford University Advisors: Bill Burnett and David Kelley Design Garage Project: Increasing Child-Parent Quality Time: identified specific user needs, and designed solutions as part of this year-long design project. Our final deliverable was a published children’s book. 2009–2013 B.Sc., Engineering: Interaction Design, Olin College of Engineering Advisor: Amon Millner Senior Capstone Project: Enhancing the Autodesk 123D Experience for Sec- ondary School Students: delivered bite-size pieces of curriculum to intro- duce 3D modeling software in various academic settings. Grand Challenge Scholar Project: Summer Camp: Motivating Students for Advanced Personalized Learning: founded a sustainability summer camp for 8–12 year-old kids based on hands-on engineering projects and experiments. Internships 2019 Google, Search User Experience Research Intern Mountain View, CA 2018 Google, Chrome User Experience Research Intern San Francisco, CA 2016 Yahoo, Flurry User Experience Research Intern Sunnyvale, CA 2012 -

Cupertino City Manager

www.peckhamandmckenney.com Search Schedule Search City of Cupertino, California Cupertino, of City City Manager City development and maintain • CalPERS 2.7% @ 55 PERS Retirement. strong regional cooperation City pays 6% of the employee Resume filing date .................................June 8, 2012 and partnerships. contribution and the employee pays the Preliminary Interviews .................. .June 11-19, 2012 remaining 2%. Given anticipated future Recommendation of Candidates ...........June 20, 2012 • CalPERS 1959 Survivor Benefit. development in Cupertino, Final Interview Process .............June 29 and 30, 2012 • Choice of health insurance with the it is expected that the Anticipated Start Date ................ September 4, 2012 employee’s premium paid by the City in new City Manager will have the ability to manage addition to portion of family premium. large projects, take a visionary approach, and be These dates have been confirmed, and it is • Fully paid vision, life, and disability recommended that you plan your calendar accordingly. in tune with long-term issues. The City Manager insurance. will be a hands-on manager, sensitive to fiscal • Partially paid dental insurance. responsibility, and utilizing technology in the • Fully paid Employee Assistance Program. best manner for efficient and effective service. • Annual Leaves - 10 to 22 days of vacation annually based on years of service with credit The Recruitment Process The selected candidate will possess proven To apply for this outstanding career leadership and management abilities as well as given for previous employment in the public opportunity, please send your resume and cover letter electronically to: a solid knowledge and understanding of local sector; 12 holidays, 20 hours of floating holiday; government services. -

Essam A. Marouf September 2019 Professional Summary

Essam A. Marouf September 2019 Professional Summary Education Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering (Major) and Computer Science (Minor), Stanford University, Stanford, California, 1975. Dissertation: The Rings of Saturn: Analysis of a Bistatic-Radar Experiment. B.S. and M.S. in Electrical Engineering (Communications), University of Alexandria, Egypt, 1965 and 1968, respectively. Areas of Expertise Digital and statistical signal processing; spectral estimation; signal reconstruction and restoration; electromagnetic wave propagation and scattering; waves in random media; Fourier and statistical optics; inverse scattering; application to planetary exploration using unmanned spacecraft. Professional Positions 2018- : Associate Dean for Graduate Studies & Research, College of Engineering, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. 2014-2017: Associate Dean for Research, College of Engineering, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. 1990- : Professor of Electrical Engineering, College of Engineering, San Jose State University, San Jose, CA. 2005-2006: Visiting Professor, Department of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, CA (on sabbatical leave from San Jose State University). 1998-1999: Senior Visiting Scientist, NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, CA (on sabbatical leave from San Jose State University) 1981-1990: Senior Research Scientist, Space Telecommunications and Radio Science (STAR) Lab, Department of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, CA. 1978-1981: Research Associate, STAR Lab, Department -

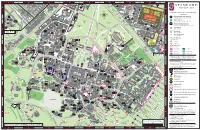

2016-2017 Directory Map with Index 09292016

S AN M AT EO DR M R BRYANT ST D A Y L RAMONA ST TASSO ST W E URBAN LN HERMOSA WY O R O U MELVILLE AV D A L L BUILDING GRID Poplar F-5 Oval, The F/G-8 N Y NeuroscienceQUARRY RD 30 Alta Road K-3 Post Office I-8 PAC 12 Plaza E-12 A B Health Center 08 Panama Mall: Housing Assignments Office H-7 Press Building I-7 Papua New Guinea Sculpture Garden I-6 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Advanced Medicine Center: ASC, Cancer Center C-5/6 Psychiatry B-8 Rehnquist Courtyard J-9 COWPER Anderson Collection D-8 Puichon G-2 Roble Field (on Roble Field Garage) H-5/6 WAVERLEY ST Hoover Sheraton PALO RD Arrillaga Alumni Center F-10 Recycling Center G-13 Rodin Sculpture Garden E-7/8 N Neuroscience Hoover William R. KELLOGG AV Art Gallery G-9 Red Barn I-2 Serra Grove G-7 SANTA RITA AV L Pavilion Hotel VIA PUEBLO Serra Shriram Center Artist's Studio K-3 Redwood Hall F-5 SEQ Courtyard G-6 BRYANT ST Pavilion Hewlett D Health Center L-1A Automotive Innovation Facility F-2 Rogers: The Bridge Peer Counseling Center J-7 Taylor Grove, Chuck E-11/12 EL CAMINO REAL EVERETT HIGH ST Downtown Grove SERRA MALL R Garage Bioengineering & U Teaching Bambi H-5/6 Science Teaching and Learning Center (Old Chemistry Building) F-7 Terman Site H-6 (see INSET 1 W A O Sequoia Barnum Center I-8/9 Sequoia Hall G-7 Toyon Grove D-10/11 LYTTON AVE Palo Alto Westin Chemical Engineering SpilkerHIGH ST E H Center B Barnes G-2 Serra (589 Capistrano Way) J-7 West Oval Grove F/G-8 RAMONA ST at upper left) L EMERSON ST S A C Hotel Hall Bechtel International Center J-7 SHC-LPCH Steam Plant -

A Strategic Overview of the Silicon Valley Ecosystem: Towards Effectively “Harnessing” the Ecosystem

A Strategic Overview of the Silicon Valley Ecosystem: Towards Effectively “Harnessing” the Ecosystem 8. University-Industry, University-Government Ties Kenji E. Kushida Universities are a critical component of the Silicon Valley ecosystem, serving as a multifaceted focal point for the exchange of human capital, ideas, technologies, and more. As such, Japanese companies that can effectively make use of universities for the variety of functions they can offer stand to benefit and become more effectively integrated into the Silicon Valley ecosystem. To do so, the first step is understanding the role of universities. The relationship between the government, universities and industries is often misunderstood as unidirectional, with the government encouraging innovations at universities by providing funding and the universities producing new ideas that are commercialized by industry. The reality observed in Silicon Valley, however, is more complex and multi-directional. The efforts for innovation are more often driven by individual researchers at universities rather than the government agencies or university administration, and initial ideas for innovation often comes from industries. The university-industries ties that contribute to the Silicon Valley ecosystem are multifaceted, diverse, and not easily captured by a single set of metrics. This in itself has caused much confusion for actors wishing to learn about Silicon Valley, not only from those outside the US, but in US media portrayals as well. This is partly because of the close relationship between the multifaceted university-government ties that anchor much of the university-industry ties. The core research universities are Stanford University and the University of California. Among the University of California schools UC Berkeley and UC San Francisco Medical Center are within the broader Silicon Valley ecosystem, with UC Davis also playing an important role, particularly in agricultural science. -

Alexander W. Bloedel

ALEXANDER W. BLOEDEL CONTACT Department of Economics [email protected] Stanford University https://web.stanford.edu/~abloedel/ 579 Jane Stanford Way +1 (203) 807-2858 Stanford, CA 94305-6072 EDUCATION PhD in Economics, Stanford University, 2021 (expected). BS in Economics, BA in Physics, Minor in Math, Duke University, 2014. REFERENCES Prof. Ilya Segal (Primary) Prof. Paul Milgrom Economics Department, Stanford University Economics Department, Stanford University +1 (650) 724-4905 +1 (650) 723-3397 [email protected] [email protected] Prof. B. Douglas Bernheim Economics Department, Stanford University +1 (650) 723-3397 [email protected] RESEARCH AND TEACHING FIELDS Primary fields: Microeconomic Theory, Information Economics, Mechanism Design. Secondary fields: Decision Theory, Behavioral Economics. JOB MARKET PAPER “The Cost of Optimally Acquired Information” (with Weijie Zhong) This paper develops a theory for the expected cost of optimally acquired information when information can be acquired sequentially and there is no explicit cost of delay. We study the “reduced-form” Indirect Cost functions for information generated by sequential minimization of a “primitive” Direct Cost function. The class of Indirect Costs is characterized by a recursive condition called Sequential Learning- Proofness. This condition is inconsistent with Prior Invariance: Indirect Costs must depend on the decision-maker’s prior beliefs. We show that Sequential Learning-Proofness provides partial optimality foundations for the Uniformly Posterior Separable (UPS) cost functions used in the rational inattention literature: a cost function is UPS if and only if it is an Indirect Cost that (i) satisfies a mild regularity condition or, equivalently, (ii) is 1 generated (only) by Direct Costs for which the optimal sequential strategy involves observing only Gaussian diffusion signals. -

Stanford University

Stanford University 20 Stanford University 20.1 Agency Overview Founded in 1891, Stanford is a private university that is governed by a Board of Trustees and a University president. The University is comprised of more than 70 undergraduate departments and seven professional graduate schools. As of 2015, the total student, faculty, and staff population is 29,523. Stanford University’s campus extends over 8,180 contiguous acres in both Santa Clara and San Mateo counties. As of 2015, the University’s unincorporated area in Santa Clara County spans 6.28 square miles. The University also owns approximately 1.81 square miles of land in the incorporated City of Palo Alto as shown in Figure 45. LAFCO of Santa Clara County Cities Service Review 283 Figure 45. Stanford University Existing Boundaries Stanford University 20.1.1 University Population and Transportation The University’s population of 28,139 is broken down by students, faculty, and staff in Table 208. Table 208. University Population University Population 2015 Students Undergraduate 7,018 Graduate 9,118 Faculty (professoriate) 2,118 Staff1 9,885 Total population 28,139 Source: Stanford Facts: 2015 1Staff totals do not include employees with the Stanford Linear Accelerator The University has implemented a comprehensive transportation demand management (TDM) program, intended to shift commuter behavior away from single-occupancy vehicles to alternate modes. The TDM Program was established as part of Stanford’s General Use Permit, which is described in Section 20.1.2. One of the TDM program’s key goals is to keep peak hour (defined as the one-hour period with the highest volume of traffic between 7:00 a.m. -

Workshop Participants and Reviewers and Contributors

Appendix F Workshop Participants and Reviewers and Contributors Cost-Effectiveness of Educational Technology Workshop, Dec. 9, 1986 David Cohen, Workshop Chairman Michigan State University East Lansing, MI Henry Becker Henry Levin David Stern The Johns Hopkins University Stanford University University of California, Berkeley Baltimore, MD Stanford, CA Berkeley, CA Edward Cavin Cecil McDermott Herbert Walberg Center for Naval Analyses Instructional Microcomputer Project University of Illinois Alexandria, VA in Arkansas Classrooms Chicago, IL Richard Clark Arkansas Department of Education University of Southern California Little Rock, AR Los Angeles, CA Stanley Pogrow Sheila Cory University of Arizona Chapel Hill-Carrboro City Schools Tucson, AZ Chapel Hill, NC W. Curtiss Priest James Kulik Center for information Technology University of Michigan and Society Ann Arbor, MI Lexington, MA The Educational Software Market Workshop, Aug. 6, 1987 Marc Tucker, Workshop Chairman Carnegie Forum on Education and the Economy Washington, DC Ellen Bialo Kathleen Hurley W. Curtiss Priest interactive Educational Systems Mindscape, Inc. Center for Information Technology Design, Inc. Northbrook, IL and Society New York, NY Lexington, MA Dwight Johnson William Gattis The Home School Paul Reese Radio Shack Education Division San Diego, CA Ralph Bunche Elementary School Tandy Corp. New York, NY Walter Koetke Wendy Harris Scholastic, Inc. Allan L. Rogers Department of Education New York, NY San Diego County Office of State of California Education Howard Merriman Sacramento, CA San Diego, CA Columbus Public Schools Brian Hawkins Columbus, OH Judy Salpeter Brown University Classroom Computer Learning Charles Philipp Providence, RI San Rafael, CA Montgomery County Public Schools Rockville, MD 242 243 Jay Sivin Julie Vargas Anne Wujcik Interactive Educational System West Virginia University TALMIS, Inc. -

2010-11 Stanford University Parking and Circulation

*$#.)(5& +,"--.-/("# %2 $(+%$$7(2% # $ (" 2 - " ! /4.-2"()* % & & 1 " - * * $ 1 & 6 /%$$-!112("# / 8&1%$-+$()* ) & (" * - $%( " 4-.#$%).*'(2% 1 %16&$("# & 84&*1-()* ' () 0.22&$8.$&2(%2 " * 1 8%$01-*()* 5 81%$)*("# + $ ,"!*,1%-$("# ) +1%.--$(&- 0$&#.&&$("# ,"%7$%("# "%61%(%2 +1&&$/$("# +1%-$&&(%2 21!-.-/(&- "&.+$(&- ,"%#"%2("# 8&1%$-+$(&- Downtown 1 5"%*%.2/$("# ,10$%("# 5%"2 $#$%$**("# )"-*"(+%4:("# 0"&&$*(+* 5"4&)$-(&- Palo Alto /.&0"-()* +"06%.2/$("# 5"%7.-)1-("# % 7.5&.-/()* !.-2)1%(!' 2 $&(+"0.-1(%$"& &'**1-("# '"&$(%2 7 0"'(6%1!-("# $ +")*&$(!' $ + % 1 ,$%01)"(!' ! 5.-$()* + "22.)1-("# 5 !.&)1-()* )"91-(!' !$%*,("# $ 6'%1-()* !.-2)1%(2% % 5%.-+$*1-(%2 () ,"%%.$*()* %1)$8.$&2(!' ! 4-.#$%).*'(("# * " "%61%(%2 & 0 Palo Alto !"#$%&$'()* &$ 0.22&$("# . " *+ Transit &.-+1&-("# 2 , Center ,157.-)("# % $& & ,"0.&*1-("# ) 5$"%(&- (& )+1**()* "- MacArthur - (0 +&".%$ " Park * 5 7.-/)&$'("# $1 & 0 ,1 (2 )"-2(,.&&(%2 Stanford 6%'"-*()* 6 % " 51&.*:$%(2% " Shopping *"))1()* %* ' , ,$%01)"(!' ! % Center 4%6"-(&- .& ) 2 &# * )"-(0"*$1(2%11 %"01-"()* 0$&#.&&$("# .$ 2 & ! & $ - 2% % , $ 4 ;4"%%'(%2 ) " $0$%)1-()* 7 & $ )"-*"(%.*"("# Sheraton 7$&&1//("# *, Hotel 2 +1**1-()* 1 2 3 ' 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 % " COWPER William R. ! 6 WAVERLEY ST #."(54$6&1 Westin ,./,()* $ 6 Hotel Hewlett Serra )$%%"(0"&& ) Downtown Hoover Pavilion $06"%+"2$%1(%2 * EVERETT Applied Teaching EL CAMINO REAL BRYANT ST Grove $%( ,16"%*()* HIGH ST Palo Alto Classic Residence (see INSET 1 Arboretum !$&&)("#$ 1%+,"%2(((&- Center A L-1 Childen's ,10$%("#Physics Center -

Duke University 2002-2003

bulletin of Duke University 2002-2003 The Fuqua School of Business University’s Mission Statement James B. Duke’s founding Indenture of Duke University directed the members of the University to “provide real leadership in the educational world” by choosing indi- viduals of “outstanding character, ability and vision” to serve as its officers, trustees and faculty; by carefully selecting students of “character, determination and application;” and by pursuing those areas of teaching and scholarship that would “most help to de- velop our resources, increase our wisdom, and promote human happiness.” To these ends, the mission of Duke University is to provide a superior liberal educa- tion to undergraduate students, attending not only to their intellectual growth but also to their development as adults committed to high ethical standards and full participa- tion as leaders in their communities; to prepare future members of the learned profes- sions for lives of skilled and ethical service by providing excellent graduate and professional education; to advance the frontiers of knowledge and contribute boldly to the international community of scholarship; to promote an intellectual environment built on a commitment to free and open inquiry; to help those who suffer, cure disease and promote health, through sophisticated medical research and thoughtful patient care; to provide wide ranging educational opportunities, on and beyond our campuses, for traditional students, active professionals and life-long learners using the power of in- formation technologies; and to promote a deep appreciation for the range of human dif- ference and potential, a sense of the obligations and rewards of citizenship, and a commitment to learning, freedom and truth. -

Stanford University Department of Public Safety Forms

Stanford University Department of Public Safety Forms Please print the necessary form, complete all requested information and add any supporting documentation. Return it to Stanford University Department of Public Safety: By Fax: 650‐725‐8485 By Campus ID Mail: Department of Public Safety Mail Code 7240 (Please allow time for mail delivery) By U.S. Mail: Stanford University Department of Public Safety Records Unit 711 Serra St. Stanford, CA 94305‐7240 (Please allow time for mail delivery) By delivery in person: Department of Public Safety 711 Serra Street Stanford, CA 94305‐7240 (Directly behind the gas station on campus) If you have any questions call the SUDPS Records Unit at 650‐723‐9633 STANFORD UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY PROCEDURE FOR CONTESTING PARKING CITATIONS All parking citations issued by members of the Stanford University Department of Public Safety (SUDPS) on Stanford University grounds are issued under the authority of Santa Clara County. SUDPS in conjunction with Santa Clara County Office of Parking Violations has implemented an Administrative Review procedure for contesting parking citations in accordance with Assembly Bill 408 (effective July 1, 1993). AB 408 established a three step process for contesting parking violations: an ADMINISTRATIVE REVIEW, an ADMINISTRATIVE HEARING, and an appeal to the SMALL CLAIMS DIVISION of the MUNICIPAL COURT. If you wish to appeal a parking citation you must, within twenty one (21) days of the date of issuance of the citation, or fourteen (14) days from the date of the mailing of the Notice of Delinquent Violation, request either an administrative review or hearing. If you do not make your request within the appropriate period of time, the law specifies that you lose your right to appeal the citation.