New Man’ and Knight of the Shire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ms Kate Coggins Sent Via Email To: Request-713266

Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Ms Kate Coggins Date: 8th January 2021 Your Ref: Our Ref: FIDP/015776-20 Sent via email to: Enquiries to: Customer Relations request-713266- Tel: (01454) 868009 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Dear Ms Coggins, RE: FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT REQUEST Thank you for your request for information received on 16th December 2020. Further to our acknowledgement of 18th December 2020, I am writing to provide the Council’s response to your enquiry. This is provided at the end of this letter. I trust that your questions have been satisfactorily answered. If you have any questions about this response, then please contact me again via [email protected] or at the address below. If you are not happy with this response you have the right to request an internal review by emailing [email protected]. Please quote the reference number above when contacting the Council again. If you remain dissatisfied with the outcome of the internal review you may apply directly to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO). The ICO can be contacted at: The Information Commissioner’s Office, Wycliffe House, Water Lane, Wilmslow, Cheshire, SK9 5AF or via their website at www.ico.org.uk Yours sincerely, Chris Gillett Private Sector Housing Manager cc CECR – Freedom of Information South Gloucestershire Council, Chief Executive & Corporate Resources Department Customer Relations, PO Box 1953, Bristol, BS37 0DB www.southglos.gov.uk FOI request reference: FIDP/015776-20 Request Title: List of Licensed HMOs in Bristol area Date received: 16th December 2020 Service areas: Housing Date responded: 8th January 2021 FOI Request Questions I would be grateful if you would supply a list of addresses for current HMO licensed properties in the Bristol area including the name(s) and correspondence address(es) for the owners. -

JLAF) for Bath & North East Somerset, Bristol City and South Gloucestershire

Joint Local Access Forum (JLAF) for Bath & North East Somerset, Bristol City and South Gloucestershire March 2018 JLAF: Background Papers Some items on the agenda are addressed verbally at the meeting, therefore, papers are not available for every item on the agenda. B: MAIN BUSINESS B3: ROWIP Joint Rights of Way Improvement Plan 2018-2026 1 JOINT RIGHTS OF WAY IMPROVEMENT PLAN: 2018-2026 Foreword Executive Summary 1) Introduction - The ROWIP Area - Joint Local Access Forum - Approach - Policy Context - ROWIP Changes 2) User Needs - Introduction - Current Patterns of Use - Walkers - Cyclists - Equestrians - Motorised Users - People with Mobility Problems - Low Participation Groups - Minimising User Conflicts - Other Interests 3) Rights of Way in the ROWIP Area - Definitive Maps and Statements - Bridleways and Byways - Extent of the Public Rights of Way Network - The Wider Access Network - Promotion - Modification and Public Path Orders - Maintenance 4) Review of Other Documents and Information - National Picture - Community and Corporate Strategies and the JLTP3 - AONB Management Plans - Other Documents and Information 5) Involving the Public and Assessment Summary - Introduction - Themes - Input into 2018 ROWIP Review 6) Statement of Action - Progress since 2007 - Statement of Action - Implementation, Funding and Partnership Working 7) Conclusion 2 Glossary of Terms Figures 1 The ROWIP area 2 Policy Context 3 Assessment Leading to Action 4 Levels of Path Use by Type 5 Typical Rights of Way Usage 6 Public Rights of Way Network 7 Bridleways and Byways Network 8 Bridleways and Byways Density 9 Access Land and ESS land with Improved Access 10 Promoted Routes Tables 1 Extent of Public Rights of Way 2 Number of Modification Orders Made 2012 to 2017 3 Number of Public Path Orders Made 2012 to 2017 4 Progress on Statement of Action 5 Statement of Action 3 FOREWORD Welcome to the Rights of Way Improvement Plan. -

A Guide to Archive Sources for the History of South Gloucestershire

A guide to archive sources for the history of South Gloucestershire Screenshot from the Know Your Place website (www.kyp.org.uk) showing historic and modern maps of Thornbury Published by Gloucestershire Archives in partnership with South Gloucestershire Council February 2018 (fifth edition) Table of contents How to use this guide .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Introduction .............................................................................................................................................................................................................. 8 Archive provision in South Gloucestershire .......................................................................................................................................................... 8 The City of Bristol and its record keeping ............................................................................................................................................................. 9 The county of Gloucestershire and its recordkeeping ........................................................................................................................................ 12 Church records .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 14 Barton -

Avonmouth and Severnside Integrated Development, Infrastructure, And

Bristol City and South Gloucestershire Councils AVONMOUTH AND SEVERNSIDE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT, INFRASTRUCTURE AND FLOOD RISK MANAGEMENT STUDY February 2012 Address: Ropemaker Court, 12 Lower Park row, Bristol, BS1 5BN Tel: 01179 254 393 Email: [email protected] www.wyg.com creative minds safe hands Document Control Project: A066776 Client: SWRDA, Bristol City Council and South Gloucestershire Council Job Number: A066776 File Origin: X: \Projects \A0 60000 -\A066776 - Avonmouth Infrastructure Study \Final Report \April 2012 \A066776 wyg report final feb 2012.doc Document Checking: Prepared by: AS Signed: AS Checked by: ND Signed: ND Verified by: ND Signed: ND Issue Date Status 1 3rd October 2011 Draft 2 22 nd December 2011 Revised Draft 3 10 th February 2011 Final Draft 4 24 th April 2012 Final Issue www.wyg.com creative minds safe hands Contents Page Executive Summary…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................4 1.1 The Opportunity.........................................................................................................................4 1.2 WYG .........................................................................................................................................4 1.3 Location ....................................................................................................................................5 1.4 Infrastructure ............................................................................................................................5 -

South Gloucestershire Council Conservative Group

COUNCIL SIZE SUBMISSION South Gloucestershire South Gloucestershire Council Conservative Group. February 2017 Overview of South Gloucestershire 1. South Gloucestershire is an affluent unitary authority on the North and East fringe of Bristol. South Gloucestershire Council (SGC) was formed in 1996 following the dissolution of Avon County Council and the merger of Northavon District and Kingswood Borough Councils. 2. South Gloucestershire has around 274,700 residents, 62% of which live in the immediate urban fringes of Bristol in areas including Kingswood, Filton, Staple Hill, Downend, Warmley and Bradley Stoke. 18% live in the market towns of Thornbury, Yate, and Chipping Sodbury. The remaining 20% live in rural Gloucestershire villages such as Marshfield, Pucklechurch, Hawkesbury Upton, Oldbury‐ on‐Severn, Alveston, and Charfield. 3. South Gloucestershire has lower than average unemployment (3.3% against an England average of 4.8% as of 2016), earns above average wages (average weekly full time wage of £574.20 against England average of £544.70), and has above average house prices (£235,000 against England average of £218,000)1. Deprivation 4. Despite high employment and economic outputs, there are pockets of deprivation in South Gloucestershire. Some communities suffer from low income, unemployment, social isolation, poor housing, low educational achievement, degraded environment, access to health services, or higher levels of crime than other neighbourhoods. These forms of deprivation are often linked and the relationship between them is so strong that we have identified 5 Priority Neighbourhoods which are categorised by the national Indices of Deprivation as amongst the 20% most deprived neighbourhoods in England and Wales. These are Cadbury Heath, Kingswood, Patchway, Staple Hill, and west and south Yate/Dodington. -

Area 15 Patchway, Filton and the Stokes

Area 15 South Gloucestershire Landscape Character Assessment Draft Proposed for Adoption 12 November 2014 Patchway, FiltonPatchway, and the Stokes Area 15 Patchway, Filton and the Stokes Contents Sketch map 208 Key characteristics 209 Location 210 Physical influences 210 Land cover 210 Settlement and infrastructure 212 Landscape character 214 The changing landscape 217 Landscape strategy 220 Photographs Landscape character area boundary www.southglos.gov.uk 207 Area 15 South Gloucestershire Landscape Character Assessment Draft Proposed for Adoption 12 November 2014 Patchway, FiltonPatchway, and the Stokes •1 â2 è18 •3 •19 •15 •21•16 å13 á14 •17 •7 å8 æ9 â13 å14 ç15 •10 •11 ã12 Figure 46 Patchway, Filton Key å15 Photograph viewpoints and the Stokes \\\ Core strategy proposed new neighbourhood Sketch Map Scale: not to scale 208 www.southglos.gov.uk Area 15 South Gloucestershire Landscape Character Assessment Draft Proposed for Adoption 12 November 2014 Patchway, FiltonPatchway, and the Stokes Area 15 Patchway, Filton and the Stokes The Patchway, Filton and the Stokes character area is an urban built up area, consisting of a mix of residential, N commercial and retail development and major transport corridors, with open space scattered throughout. Key Characteristics ¡ This area includes the settlements of ¡ Open space is diverse, currently including Patchway and Filton plus Bradley Stoke, areas of Filton Airfield much of which is Stoke Gifford, Harry Stoke and Stoke Park. proposed for development, as well as within the railway junction, the courses ¡ Largely built up area, bounded by of Patchway Brook and Stoke Brook, motorways to the north west and north part of historic Stoke Park and remnant east, with railway lines and roads dividing agricultural land. -

Ifford to the South and Bradley Stoke to the North

West of England Full Business Case Programme: Early Investment Scheme: Great Stoke Roundabout Capacity Improvement Originated Reviewed Authorised Date 1 Version 1.5 VH 2 Version1.6 TA VH 3 Version 1.7 TA VH 4 Version 1.8 RG 19/7/19 5 Version 1.9 TA RG 22/7/19 Version 2.0 VH Executive Summary Great Stoke Roundabout is located in South Gloucestershire on the boundary of Stoke Gifford to the south and Bradley Stoke to the north. It is on the edge of the Bristol urban area close to residential, industrial and commercial areas. There are a number of developments close by in the North Fringe such as Cribbs Patchway New Neighbourhood (CPNN), Horizon 38, Charlton Hayes, Harry Stoke New Neighbourhood and Haw Wood. The North Fringe of Bristol is a major economic hub within the region, which is continuing to expand with the Filton Enterprise Area (FEA) being identified in the West of England Spatial Plan (JSP) as a key strategic employment location. It is also a key component to the region’s housing strategy, with approximately 7,700 dwellings committed in the South Gloucestershire Core Strategy (CS) as part of the CPNN and Harry Stoke developments. The roundabout currently experiences delays to traffic during the peak periods and is forecast to become progressively worse as the local developments are implemented leading to increased levels of congestion. This junction is therefore expected to considerably restrict traffic movements from a key transport interchange at Bristol Parkway and the access to the economic centre of South Gloucestershire within the Bristol North Fringe. -

Urban Localities Review of Potential

South Gloucestershire Urban Localities: Review of Potential Description, Context and Principles November 2017 URB AN S O U T H G L O U C E S T E R S H I R E BRISTOL Contact details: Bath Office: 23a Sydney Buildings, Bath BA2 6BZ Phone: 01225 442424 Bristol Office: 25 King Street, Bristol BS1 4PB Phone: 0117 332 7560 Website: www.nashpartnership.com Email: [email protected] Twitter: @nashPLLP File Reference 16053_U07_001 Date of Issue November 2017 Revision G Status Final Prepared by Mel Clinton, Edward Nash and Leigh Dennis Design by Julie Watson Authorised by Mel Clinton File Path 16053_U07_001_Review of Potential Report 2 Contents Executive Summary 4 1 Introduction 9 2 The Localities 11 3 Strategic Context 18 4 Planning and Transport Policy Framework 47 5 The Story of Place 59 6 Principles for Development and Change 76 APPENDICES 80 Appendix 1: Socio-Economic Summary Profiles by Locality Appendix 2: Socio-Economic Analysis Census Data Used to Inform Appendix 3: Ownership in the Localities by Housing Associations 3 Executive Summary Introduction Hanham and Environs Yate Station and Environs South Gloucestershire Council is one of the four West of England authorities (Bristol All of these, with the exception of Yate, directly adjoin the Bristol City Council City Council, Bath and North East Somerset Council and North Somerset Council) administrative area, forming the north and east fringe of the wider urban area. working on a Joint Spatial Plan for the period 2016-2036. This will set out a framework for strategic development as the context for the Local Plans of each authority. -

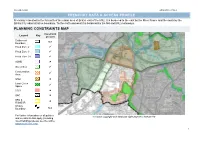

Frenchay Data & Access Profile

November 2020 Urban Place Profiles FRENCHAY DATA & ACCESS PROFILE Frenchay is located to the far north of the urban area of Bristol east of the M32. It is bordered to the east by the River Frome and the south by the Bristol City administrative boundary. To the north and west it is bordered by the M4 and M32 motorways. PLANNING CONSTRAINTS MAP Constraint Legend Key present Settlement N/A Boundary Flood Zone 2 Flood Zone 3 Flood Zone 3B AONB Green Belt Conservation Area SAM Local Green Space SSSI SAC SPA & RAMSAR Unitary Boundary N/A For further information on all policies © Crown copyright and database right 2020 OS 100023410 and constraints that apply (including listed buildings) please see the online adopted policies map. 1 November 2020 Urban Place Profiles KEY DEMOGRAPHIC STATISTICS POPULATION & HOUSEHOLD Population Additional Households dwellings Total 0-4 5-15 16-64 65+ 2011 completed 2011 Census since 1,965 100 199 1,116 550 Census 2011* 2018 MYE 2,038 68 260 1,146 563 880 248 % change 4% -31% 31% 3% 2% 2011 to 2018 *Based on residential land survey data 2011 CENSUS ECONOMIC ACTIVITY Economically No. Unemployed % Unemployed Active Frenchay 892 32 3.6% South Gloucestershire 143,198 5,354 3.7% Total 2011 CENSUS COMMUTER FLOWS The following section presents a summary of the commuter flows data for each area. The number of ‘resident workers’ and ‘workplace jobs’ are identified and shown below. Key flows between areas are also identified ‐ generally where flows are in excess of 5% Jobs Workers Job/Worker Ratio 4,920 870 5.7 According to 2011 Census travel to work data there were around 900 ‘working residents’ living in the area. -

Infrastructure Delivery Plan (March 2014)

South Gloucestershire Infrastructure Delivery Plan March 2014 Infrastructure Delivery Statement – Supporting Explanation Planning for infrastructure to meet existing deficiencies and future growth is a high priority for the Council. It therefore continues to work closely with its development partners, the West of England Partnership (4UAs) and other statutory and non-statutory organisations to identify and bring forward new and improve existing infrastructure. The information shown in the following matrix reflects the current position at the time of writing [March 2014] based on information available to the Council. The IDP is thus subject to continual update and review as new information becomes available. It is proposed therefore that it is a 'living document'. The IDP matrix should be read in conjunction with the supporting Evidence Appendices. The following tables give a broad indication of the planned provision, cost and need for infrastructure in South Gloucestershire (to 2027). It sets out planned infrastructure to meet existing deficiencies where information is available, plus that required to meet growth as set out in the South Gloucestershire Local Plan 2006 & Core Strategy (Dec 2013). It thereby indicates requirements for additional infrastructure which would not have been necessary but for the implementation of the proposed development. Where available, items contained within existing S106 agreements for major development sites (or agreements in advanced states of negotiation) have been reflected. For clarity these major sites are Emersons Green Science Park, Charlton Hayes, Harry Stoke, Emersons Green East, Park Farm –Thornbury, North Yate New Neighbourhood & University of the West of England. These sites may from time to time, be subject to change due to negotiation and viability testing instigated by the respective developers. -

The Skidmore and Scudamore Families of Frampton Cotterell, Gloucestershire 1650-1915

Skidmore (Scudamore) Families of Frampton Cotterell Linda Moffatt © 2015 THE SKIDMORE AND SCUDAMORE FAMILIES OF FRAMPTON COTTERELL, GLOUCESTERSHIRE 1650-1915 by Linda Moffatt © 2015 1st edition 2012, published at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com 2nd edition 2015, published at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com This is a work in progress. The author is pleased to be informed of errors and to receive additional information for consideration for future updates at [email protected] This file was last updated by Linda Moffatt on 8 March 2016. DATES Prior to 1752 the year began on 25 March (Lady Day). In order to avoid confusion, a date which in the modern calendar would be written 2 February 1714 is written 2 February 1713/4 - i.e. the baptism, marriage or burial occurred in the 3 months (January, February and the first 3 weeks of March) of 1713 which 'rolled over' into what in a modern calendar would be 1714. Civil registration was introduced in England and Wales in 1837 and records were archived quarterly; hence, for example, 'born in 1840Q1' the author here uses to mean that the birth took place in January, February or March of 1840. Where only a baptism date is given for an individual born after 1837, assume the birth was registered in the same quarter. BIRTHS, MARRIAGES AND DEATHS Databases of all known Skidmore and Scudamore bmds can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com PROBATE A list of all known Skidmore and Scudamore wills - many with full transcription or an abstract of its contents - can be found at www.skidmorefamilyhistory.com in the file Skidmore/Scudamore One-Name Study Probate. -

ROY PREDDY FUNERAL DIRECTORS 2 Cossham Street, Mangotsfield BS16 9EN (0117) 9562834

Focal Point, January 2015 ROY PREDDY FUNERAL DIRECTORS 2 Cossham Street, Mangotsfield BS16 9EN (0117) 9562834 We are at your service 24 hours a day We will help and guide you every step of the way We will guide you through our choice of funeral plans We can help and advise you choose a memorial We are members of the National Association of Funeral Directors Our other Bristol businesses can similarly help you - Roy Preddy - Kingswood (0117) 9446051 TB & H Pendock - Hambrook (0117) 9566774 Stenner & Hill - Shirehampton (0117) 9823188 R. Davies & Son - Westbury-on-Trym (0117) 9628954 R. Davies & Son - Horfield (0117) 9424039 R. Davies & Son - Bishopsworth (0117) 9641133 Whitchurch FS - Whitchurch (01275) 833441 Part of Dignity Ltd, a British Company 1 Focal Point, November 2017 2 Focal Point, November 2017 We can offer various sizes of adverts in Focal Point to suit your needs. Contact the editor on 932 5037 or email [email protected] 3 Focal Point, November 2017 4 Focal Point, November 2017 5 Focal Point, November 2017 6 6 FocalS M Point, Wilkins November Electrical 2017 Services FREE QUOTES COMPETITIVE RATES FULLY INSURED SIX-YEAR WARRANTY OVER 20 YEARS’ EXPERIENCE • Testing & inspection • Extra sockets/lights • Landlord certs (EICR) • Cooker/shower installation • Fault finding/repairs • Smoke alarms Mobile: 0771 218 9118 Email: [email protected] 7 Focal Point, November 2017 8 Focal Point, November 2017 USEFUL CONTACTS Bitton AFC Bitton Gardening Club (Western League Premier Division) St Mary’s Church