Public Awareness and Auto-Theft Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Public Awareness and Auto-Theft Prevention: Getting It Right for the Wrong Reason

Security Journal ELSEVIER Security Journal 10 (1998)59-64 Public awareness and auto-theft prevention: getting it right for the wrong reason Richard Wortley*, Rebecca Kane, Frances Gant School of Justice Administration, Griffith University, Brisbane 4111, Australia Received 3 November 1997; revised 26 November 1997; accepted 26 November 1997 Abstract This article reports an evaluation of a public awareness campaign aimed at encouraging the use of car security measures, particularly Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) etching. It was found that the campaign coincided with an immediate reduction in the incidence of auto-theft. However, there did not appear to be any significant change in the behavior of car owners which would account for this reduction. Rather, it seems the reduction in thefts may have come about through an increased perception of risk the campaign generated among potential car thieves. © 1998 Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd. Keywords: Auto-theft prevention; Vehicle identification; Publicity and crime prevention; Police-private sector co-operation 1. Introduction major insurance companies and motorist organiza- tions, developed Project HEAT (Help Eliminate Auto Motor vehicle theft in Australia is widespread, gen- Theft). HEAT was a community awareness campaign erally exceeding figures for foreign industrialized na- whose principle aim was to" encourage the use of tions (Higgins, 1997, p. 4) and over the past decade security devices and, in particular, the etching of the has emerged as one of the nation's fastest growing Vehicle Identification Number (VIN) on car windows. crimes. Domestically, this crime costs the Australian The campaign was state-wide, although there was a community approx. A$l billion annually and, if theft special focus on the south-east corner of the state rates cannot be curbed, costs are destined to inflate in where the population is concentrated and where 73% the future as the cost of automobiles, insurance of all state auto-theft occurs. -

Auto Theft Is BIG Business and Auto Thieves May Want YOUR Vehicle!

Auto Theft is BIG Business and auto thieves may want YOUR vehicle! Protect your vehicle the best you can and join the Watch Your Car Program Most Commonly Stolen Vehicles…Is Yours One of Them? Top 10 Most Commonly Stolen Top 10 Most Commonly Stolen Vehicles for 2008 – Nationwide Vehicles for 2008 – Arizona 1. 1994 Honda Accord 1. 2004 Dodge Ram Pickup 2. 1995 Honda Civic 2. 1994 Honda Accord 3. 1989 Toyota Camry 3. 1995 Honda Civic 4. 1997 Ford F150 4. 1997 Ford F150 Pickup 5. 2004 Dodge Ram Pickup 5. 2003 Ford F250 Pickup 6. 2000 Dodge Caravan 6. 1994 Nissan Sentra 7. 1996 Jeep Cherokee/Grand Cherokee 7. 1990 Toyota Camry 8. 1994 Acura Integra 8. 2006 Ford F350 Pickup 9. 1999 Ford Taurus 9. 2000 Chevrolet 4x2 Pickup 10. 2002 Ford Explorer 10. 2004 Chevrolet Ext Cab 4x2 Pickup Anti-Theft Tips… Professional thieves can steal any car, but make them work for yours. To prevent thefts, the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB) recommends “Layered Protection.” The more layers of protection on your vehicle, the more difficult it is to steal. The number of layers your vehicle needs varies depending on your vehicle and geographic location. Your budget and personal preferences should determine which anti-theft device is best for you. Layer #1 – Common Sense An unlocked vehicle with a key in the ignition is an open invitation to any thief, regardless of which anti- theft device you use. The common sense approach to protection is the simplest and most cost- effective way to thwart would-be thieves. -

AUTO THEFT and WINDOW ETCHING Arizona Automobile Theft Authority Recommends a Layered Approach to Auto Theft Protection

AUTO THEFT AND WINDOW ETCHING Arizona Automobile Theft Authority recommends a layered approach to auto theft protection: Layer 1 – Practice Common Sense. Always lock your vehicle and take the keys with you. Never leave your vehicle running and unattended. Park in well-lit areas. Layer 2 – Use Visible and Audible Warning Devices. Enroll in the free watch your car program. Have your vehicle’s VIN etched on windows. Use a steering wheel or brake lock. Install an audible alarm. Layer 3 – Use Immobilizing Devices. Install a kill switch. Use starter, ignition, fuel disablers, or a smart key. Layer 4 – Use a Tracking Device. They emit a signal to police or monitoring stations when vehicles are stolen. These devices are effective in helping law enforcement recover stolen vehicles. Automobile Window Etching V.I.N. etching is the process of permanently etching your vehicle's seventeen (17) digit vehicle identification number on each piece of glass window on the vehicle. Etching your vehicle's V.I.N. serves as a permanent fingerprint of your vehicle. It is considered an effective deterrent against auto theft. When a vehicle is stolen, the thief must change the identity of the vehicle by changing the V.I.N. plate on the dashboard or else risk being discovered by law enforcement. With a new V.I.N. plate, the thief now has a "new" vehicle, but if the V.I.N. is etched on the windows, the thief must dispose of and replace all windows, which is costly and time consuming. As the thief contemplates stealing your car, he/she will notice the glass etching and may move on to an easier target vehicle. -

Clay Modeling, Human Engineering and Aerodynamics in Passenger Car

^ 03 CLAY MODELING, HU>L\N ENGINEERING AND AERODYNAMICS IN PASSENGER CAR BODY DESIGN /^? by AJITKUMAR CHANDRAICANT KAPADIA B.E. (M.E.)> Maharaja Sayajirao University Baroda, India, 1962 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Industrial Engineering KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 1965 Appro/^ed by: 6 |9^5 TABLE OF CONTENTS ^P' INTRODUCTION 1 PURPOSE 3 MODELING OF PASSENGER G\RS 4 Sketches 4 Clay Models 5 APPLICATION OF HUMAN ENGINEERING / Design of Seat and Its Relative Position / 7 Design of Controls and Displays 28 AERODYNAMIC TESTING OF PASSENGER CARS 37 Aerodynamic Drag 40 Internal Flow Requirements 44 External flow pattern 45 Aerodynamic Noise 45 SU14MARY 47 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 50 REFERENCES 51 INTRODUCTION The history of the American automobile began when Dureay's demonstrated his first car in 1893. Horse-carts and chariots were the main vehicles up through the 19th century, but men dreamt of self-propelled highway vehicles. The invention of the internal combustion engine, with its compact size as compared to that of the steam engine helped realize this dream. These self-propelled automobiles were so novel to people that the engi- neers did not worry much about their shape and size. They mainly consisted of the engine and its components, wheels, and a seat on top with a steering device. Later, this seat was replaced by a carriage to accommodate more persons. These early cars were quite high mounted on the axles with open engine, that is, without any hood to cover the engine. -

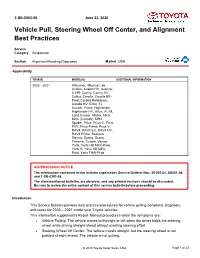

Vehicle Pull, Steering Wheel Off Center, and Alignment Best Practices

T-SB-0063-20 June 23, 2020 Vehicle Pull, Steering Wheel Off Center, and Alignment Best Practices Service Category Suspension Section Alignment/Handling Diagnoses Market USA Applicability YEAR(S) MODEL(S) ADDITIONAL INFORMATION 2002 - 2021 4Rrunner, 4Runner, 86, Avalon, Avalon HV, Avanza, C-HR, Camry, Camry HV, Celica, Corolla, Corolla BR- Prod, Corolla Hatchback, Corolla HV, Echo, FJ Cruiser, Hiace, Highlander, Highlander HV, Hilux, iA, iM, Land Cruiser, Matrix, Mirai, Mirai (Canada), MR2 Spyder, Prius, Prius C, Prius PHV, Prius Prime, Prius V, RAV4, RAV4 EV, RAV4 HV, RAV4 Prime, Sequoia, Sienna, Solara, Supra, Tacoma, Tundra, Venza, Yaris, Yaris HB MEX-Prod, Yaris R, Yaris SD MEX- Prod, Yaris THAI-Prod SUPERSESSION NOTICE The information contained in this bulletin supersedes Service Bulletin Nos. ST005-01, SU001-08, and T-SB-0391-08. The aforementioned bulletins are obsolete, and any printed versions should be discarded. Be sure to review the entire content of this service bulletin before proceeding. Introduction This Service Bulletin provides best practice procedures for vehicle pulling complaint, diagnosis, and repair for 2002 – 2021 model year Toyota vehicles. This information supplements Repair Manual procedures when the symptoms are: Vehicle Pulling: The vehicle moves to the right or left when the driver holds the steering wheel while driving straight ahead without exerting steering effort. Steering Wheel Off Center: The vehicle travels straight, but the steering wheel is not pointed straight ahead. The vehicle is not pulling. © 2020 Toyota Motor Sales, USA Page 1 of 23 T-SB-0063-20 June 23, 2020 Page 2 of 23 Vehicle Pull, Steering Wheel Off Center, and Alignment Best Practices Introduction (continued) Before repairing a vehicle pulling to one side, it is necessary to clearly identify the cause of the pulling condition. -

A Novel Chassis Concept for Power Steering Systems Driven by Wheel Individual Torque at the Front Axle M

25th Aachen Colloquium Automobile and Engine Technology 2016 1 A Novel Chassis Concept For Power Steering Systems Driven By Wheel Individual Torque At The Front Axle M. Sc. Philipp Kautzmann Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Institute of Vehicle System Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany M. Sc. Jürgen Römer Schaeffler Technologies AG & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany Dr.-Ing. Michael Frey Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Institute of Vehicle System Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany Dr.-Ing. Marcel Ph. Mayer Schaeffler Technologies AG & Co. KG, Karlsruhe, Germany Summary The project "Intelligent Assisted Steering System with Optimum Energy Efficiency for Electric Vehicles (e²-Lenk)" focuses on a novel assisted steering concept for electric vehicles. We analysed different suspensions to use with this innovative power steering concept driven by wheel individual drive torque at the front axle. Our investigations show the potential even for conventional suspensions but reveal the limitations of standard chassis design. Optimized suspension parameters are needed to generate steering torque efficiently. Requirements arise from emergency braking, electronic stability control systems and the potential of the suspension for the use with our steering system. In lever arm design a trade-off between disturbing and utilizable forces occurs. We present a new design space for a novel chassis layout and discuss a first suspension design proposal with inboard motors, a small scrub radius and a big disturbance force lever arm. 1 Introduction Electric vehicles are a promising opportunity to reduce local greenhouse gas emissions in transport and increase overall energy efficiency, as electric drivetrain vehicles operate more efficiently compared to conventionally motorized vehicles. The internal combustion engine of common vehicles not only accelerates the vehicle, but also supplies energy to on-board auxiliary systems, such as power-assisted steering, which reduces the driver’s effort at the steering wheel. -

2021 Cadillac XT4 Owner's Manual

21_CAD_XT4_COV_en_US_84533014B_2020OCT27.pdf 1 9/25/2020 1:45:28 PM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K 84533014 B Cadillac XT4 Owner Manual (GMNA-Localizing-U.S./Canada/Mexico- 14584367) - 2021 - CRC - 10/14/20 Introduction model variants, country specifications, Contents features/applications that may not be available in your region, or changes Introduction . 1 subsequent to the printing of this owner’s manual. Keys, Doors, and Windows . 6 Refer to the purchase documentation Seats and Restraints . 36 relating to your specific vehicle to Storage . 84 confirm the features. Instruments and Controls . 90 The names, logos, emblems, slogans, Keep this manual in the vehicle for vehicle model names, and vehicle quick reference. Lighting . 129 body designs appearing in this manual Infotainment System . 136 including, but not limited to, GM, the Canadian Vehicle Owners GM logo, CADILLAC, the CADILLAC Climate Controls . 197 A French language manual can be Emblem, and XT4 are trademarks and/ obtained from your dealer, at Driving and Operating . 203 or service marks of General Motors www.helminc.com, or from: LLC, its subsidiaries, affiliates, Vehicle Care . 281 or licensors. Propriétaires Canadiens Service and Maintenance . 357 For vehicles first sold in Canada, On peut obtenir un exemplaire de ce Technical Data . 370 substitute the name “General Motors guide en français auprès du ” Customer Information . 374 of Canada Company for Cadillac concessionnaire ou à l'adresse Motor Car Division wherever it suivante: Reporting Safety Defects . 384 appears in this manual. Helm, Incorporated OnStar . 387 This manual describes features that Attention: Customer Service Connected Services . 392 may or may not be on the vehicle 47911 Halyard Drive because of optional equipment that Plymouth, MI 48170 Index . -

Car Thieves Take the Bait Car Thieves

Car Thieves Take the Bait April 24, 2007 SHARE THIS DOWNLOAD TO PDF Modesto, CA Records Dramatic Vehicle Theft Reduction; Las Vegas, NV Now Ranks as Country's Number One Metro Area With Highest Theft Rate NICB - National Insurance Crime Bureau Contact: Frank Scafidi 916.979.7025 [email protected] Des Plaines, IL, April 24, 2007 - The National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB) reported today that after three consecutive years as the area with the worst per capita vehicle theft rate in the nation, Modesto, CA has fallen into the number five position-a dramatic improvement. Taking over the "Number One Hot Spot" is Las Vegas, NV. As in 2005, the western United States still ranks as the area of the country with the highest auto theft rates. All of the nation's top ten areas are in the west with five of them in California. For 2006, the ten metropolitan statistical areas with the highest vehicle theft rates are: 1. Las Vegas/Paradise, NV 2. Stockton, CA 3. Visalia/Porterville, CA 4. Phoenix/Mesa/Scottsdale, AZ 5. Modesto, CA 6. Seattle/Tacoma/Bellevue, WA 7. Sacramento/Arden-Arcade/Roseville, CA 8. Fresno, CA 9. Yakima, WA 10. Tucson, AZ According to Hot Spots, its annual report on auto theft rates, NICB reviewed data supplied by the National Crime Information Center (NCIC) for each of the nation's 361 Metropolitan Statistical Areas (MSAs). MSAs are designated by the Office of Management and Budget and may include areas surrounding a specific city. The rate is determined by the number of vehicle theft offenses per 100,000 inhabitants using the 2005 U.S. -

FORMULA STEERING WHEEL User Manual

FORMULA STEERING WHEEL User Manual Formula Steering Wheel User manual Release 1.02 To the owner of Formula Steering wheel The new Formula Steering Wheel belongs to the last generation of AIM dashes for car racings and provides the driver with an high technology steering wheel with an innovative design. With anodised chassis, ergonomically shaped, hand-woven suede covered the Formula Steering Wheel has a real “racing look”. Thanks to AIM ECT (Easy Connection Technology), the connection with AIM products and external expansion modules comes in a click. Formula Steering Wheel allows to monitor RPM, speed, engaged gear, lap (split) times and custom sensors. Formula Steering Wheel, moreover, is configurable with Race Studio 2 software, that can be freely downloaded from www.aim-sportline.com. www.aim-sportline.com 2 Formula Steering Wheel User manual Release 1.02 INDEX Chapter 1 – Characteristics and part number ........................................................ 4 1.1 – Part Number ............................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter 2 – How to connect Formula Steering wheel to EVO .............................. 5 2.1 – Connection with EVO3 Pro ....................................................................................................... 5 2.2 – Connection with EVO3 Pista/EVO4 .......................................................................................... 5 2.3 – Connection with other AIM peripherals .................................................................................. -

Controls Near the Steering Wheel

Controls Near the Steering Wheel The two levers on the steering VEHICLE HEADLIGHTS/ HAZARD WARNING WINDSHIELD column contain controls for driving STABILITY TURN SIGNALS LIGHTS WIPERS/WASHERS features you use most often. The left ASSIST SYSTEM lever controls the turn signals, OFF SWITCH headlights, and high beams. The CRUISE right lever controls the windshield CONTROL washers and wipers. The switch for the hazard warning lights is on the dashboard to the right of the steering column. The controls under the left air vent are for the cruise control, instrument panel brightness and the VSA System. The switches for the rear window defogger and fog lights are under the audio system. INSTRUMENT The steering wheel adjustment PANEL switch on the side of the steering BRIGHTNESS column allows you to tilt and HORN FOG LIGHTS telescope the steering wheel. STEERING WHEEL REAR WINDOW ADJUSTMENTS DEFOGGER Instruments and Controls Controls Near the Steering Wheel Headlights If you leave the lights on with the ignition switch in ACCESSORY (I) or LOCK (0), you will hear a reminder chime when you open the driver's door. On cars with automatic lighting When the light switch is in either of these positions, the Lights On indicator comes on as a reminder. This light remains on if you leave the light switch on and turn the ignition switch to ACCESSORY (I) or LOCK (0). The rotating switch on the left lever To change between low beams and controls the lights. Turning this high beams, pull the turn signal lever switch to the position turns on until you hear a click, then let go. -

Instruction Manual

ADVANCED FHSS RADIO CONTROL SYSTEM INSTRUCTION MANUAL WARNING and SAFETY PRECAUTION The following terms are used throughout the product literature to indicate various levels of poten- tial harm when operating this product. CAUTION: Procedures, which if not be properly followed, is able to create a possibility of physical property damage AND or possibility of injury. ATTENTION: Read the ENTIRE instruction manual to become familiar with the features of the product before operating. Fail to operate the product correctly can result in damage to the product, personal property and cause serious injury. ATTENTION: This is a sophisticated hobby product and NOT a toy. It must be operated with cau- tion and common sense and requires some basic mechanical ability. Fail to operate this Product in a safe and responsible manner could result in injury or damage to the product or other property. This product is not intended for use by children without direct adult supervision. Do not attempt to disassemble, use with incompatible components or augment product in any way without the approval of Varioprop. This manual contains instructions for safety, operation and maintenance. It is essential to read and follow all the instructions and warnings in the manual, prior to assembly, setup or use, in order to operate correctly and avoid damage or serious injury. Age Recommendation: Not for Children under 14 years. This is not a toy. SPECIFICATIONS • 2CH Transmitter with 2-channel S2R receiver. • The device has an integrated 2.4GHz antenna. • 7: 3 and 5: 5 Throttle regulator, reverse switches for throttle and steering. • Steering DUAL RATE (D/R). -

Eyes on the Road, Hands on the Wheel: Thumb-Based Interaction Techniques for Input on Steering Wheels Iván E

Eyes on the Road, Hands on the Wheel: Thumb-based Interaction Techniques for Input on Steering Wheels Iván E. González,1* Jacob O. Wobbrock,2 Duen Horng Chau,1 Andrew Faulring1 and Brad A. Myers1 1 Human-Computer Interaction Institute 2 The Information School School of Computer Science University of Washington Carnegie Mellon University Mary Gates Hall, Box 352840 Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Seattle, WA 98195-2840 {ieg, dchau, faulring, bam}@cs.cmu.edu [email protected] ABSTRACT The increasing quantity and complexity of in-vehicle systems creates a demand for user interfaces which are suited to driving. The steering wheel is a common location for the placement of buttons to control navigation, entertainment, and environmental systems, but what about a small touchpad? To investigate this question, we embedded a Synaptics StampPad in a computer game steering wheel and evaluated seven methods for selecting from a list of over 3000 street names. Selection speed was meas- ured while stationary and while driving a simulator. Results show that the EdgeWrite gestural text entry method is about 20% to 50% faster than selection-based text entry or direct list-selection methods. They also show that methods with slower selection speeds generally resulted in faster driving speeds. However, with EdgeWrite, participants were able to maintain their speed and avoid incidents while selecting and driving at the same time. Al- though an obvious choice for constrained input, on-screen key- boards generally performed quite poorly. CR Categories: H.5.2. Information interfaces and presentation: User interfaces — Input devices and strategies. Figure 1. The first author performing input on a small touchpad with his right thumb during simulated driving.