Cost-Benefit Analysis of Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Water

LIVING WITH WATER: LIVING WITH WATER: LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM Living with Water: Lessons from Singapore and Rotterdam documents the journey of two unique cities, Singapore and Rotterdam—one with too little water, and the other with too LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM LESSONS much water—in adapting to future climate change impacts. While the WITH social, cultural, and physical nature of these cities could not be more different, Living with Water: Lessons from Singapore and Rotterdam LIVING captures key principles, insights and innovative solutions that threads through their respective adaptation WATER: strategies as they build for an LESSONS FROM uncertain future of sea level rise and intense rainfall. SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM LIVING WITH WATER: LESSONS FROM SINGAPORE AND ROTTERDAM CONTENTS About the organisations: v • About the Centre for Liveable Cities v • About the Rotterdam Office of Climate Adaptation v Foreword by Minister for National Development, Singapore vi Foreword by Mayor of Rotterdam viii Preface by the Executive Director, Centre for Liveable Cities x For product information, please contact 1. Introduction 1 +65 66459576 1.1. Global challenges, common solutions 1 Centre for Liveable Cities 1.2. Distilling and sharing knowledge on climate-adaptive cities 6 45 Maxwell Road #07-01 The URA Centre 2. Living with Water: Rotterdam and Singapore 9 Singapore 069118 2.1. Rotterdam’s vision 9 [email protected] 2.1.1. Rotterdam’s approach: Too Much Water 9 2.1.2. Learning to live with more water 20 Cover photo: 2.2. A climate-resilient Singapore 22 Rotterdam (Rotterdam Office of Climate Adaptation) and “Far East Organisation Children’s Garden” flickr photo by chooyutshing 2.2.1. -

Kallang River to Be Rejuvenated

Kallang River to Be Rejuvenated On 29 March, the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) launched a new exhibition titled “A River Runs Through It”. This exhibition is a call for public feedback on a preliminary conceptual plan to improve connectivity along the 14kmlong Kallang River, and to revitalise the areas around it. Minister for National Development and Second Minister for Finance Mr Lawrence Wong officiated at the launch of the exhibition. Potential for Rejuvenation Aerial view of possible enhancements along the Kallang River The Kallang River is Singapore’s longest natural river. Originating from Lower Peirce Reservoir, the river passes through many housing and industrial areas such as Ang Mo Kio, Bishan, Toa Payoh, Bendemeer, and Kallang Bahru before merging into the Kallang Basin. Some 800,000 people now live within 2km of the Kallang River. Over the next 20 years, there is potential to introduce another 100,000 dwelling units into the area. Waterfront rejuvenation started in the 1980s in Singapore, following the cleanup of both the Singapore River and the Kallang Basin. Over the past 30 years, the government has focused on the Singapore River, Marina Bay, and the Kallang Basin. The time is ripe to begin discussions about the further rejuvenation of the Kallang River. URA also hopes to upgrade underpasses and to build new ones in the area, including one under Sims Avenue that would help connect Kallang MRT station to the Singapore Sports Hub. Pedestrian crossings at Serangoon Road and Bendemeer Road are also expected to be widened to facilitate cycling. The existing CTE crossing could be widened and deepened for a more conducive environment for active mobility Currently, cyclists travelling along the Kallang River face several obstacles, including an 83step climb with their bicycles up a pedestrian overhead bridge across the PanIsland Expressway (PIE) and a 47 step descent on the other side. -

From Design to Data: Water Quality Monitoring

From Design to Data: Water Quality Monitoring Adapted from Healthy Water, Healthy People Educators Guide – www.projectwet.org Students create a study design, then analyze the data to simulate the process of water quality monitoring. Contents Summary and Objectives.....................................................................................Page 1 Background........................................................................................................Page 1 Warm Up............................................................................................................Page 3 Water Quality Monitoring Parameters....................................................................Page 4 The Activity: Part I...............................................................................................Page 4 The Activity: Part II..............................................................................................Page 5 Wrap Up............................................................................................................Page 6 Assessment & Extensions...................................................................................Page 6 Table Monitoring Goals - Teacher Copy Page.........................................................Page 7 Table Monitoring Worksheet - Student Copy Page..................................................Page 8 Kallang River Worksheet - Student Copy Page.......................................................Page 9 Kallang River Data Set - Student Copy Page.............................................................Page -

Forging Ahead

FY2019 Annual Report FORGING AHEAD DELIVERING WORLD-CLASS PRIMARY CARE FORGING AHEAD The National Healthcare Group Polyclinics’ (NHGP) Annual Report FY2019, titled ‘Forging Ahead’, showcases our journey in delivering quality primary care. To provide care that is world-class, we must be prepared to challenge old ideas and break new ground. The paper-cutting imagery on the cover and throughout the Annual Report depicts how NHGP has navigated through the intricacies and complexities of primary healthcare, forged ahead in the face of challenges, and found breakthroughs as part of this journey. On the cover, the burst of colours and the blooming petals portray the collaborative synergy of our staff and partners as well as our constant drive to meet the growing needs of Singapore’s population. This journey of constant growth and discovery has made NHGP a leader in advancing Family Medicine and transforming primary healthcare for the benefit of all Singaporeans. CONTENTS OUR VISION To be the leading health-promoting institution that helps advance Family Medicine and transform 04 06 08 primary healthcare in Singapore. GROUP CEO’S MESSAGE CEO’S MESSAGE NHGP SENIOR MANAGEMENT OUR MISSION We will improve health and reduce illness through 10 18 24 patient-centred quality primary healthcare that is accessible, seamless, comprehensive, appropriate and cost-effective in an CHAPTER 1 CHAPTER 2 CHAPTER 3 environment of continuous learning and relevant research. Combatting a Developing Population Charting Our Way Global Pandemic Health Forward OUR VALUES 32 36 People-Centredness Compassion CHAPTER 4 CHAPTER 5 We value diversity, respect each other We care with love, humility Advancing Towards a Enhancing Our and encourage joy in work. -

853M Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

853M bus time schedule & line map 853M Upp East Coast Ter View In Website Mode The 853M bus line (Upp East Coast Ter) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Upp East Coast Ter: 5:40 AM - 11:25 PM (2) Yishun Int: 6:00 AM - 11:17 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 853M bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 853M bus arriving. Direction: Upp East Coast Ter 853M bus Time Schedule 71 stops Upp East Coast Ter Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:40 AM - 11:25 PM Monday Not Operational Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Int (59009) Tuesday Not Operational Yishun Ctrl 1 - Opp Blk 932 (59669) 30A Yishun Central 1, Singapore Wednesday Not Operational Yishun Ctrl 2 - Yishun Community Hosp (59619) Thursday Not Operational 100 Yishun Central, Singapore Friday Not Operational Yishun Ave 2 - Blk 608 (59059) Saturday Not Operational 612 Yishun Street 61, Singapore Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Khatib Stn (59049) Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Sports Hall (59039) 853M bus Info Direction: Upp East Coast Ter Lentor Ave - Aft Yishun Ave 1 (59029) Stops: 71 Trip Duration: 117 min Lentor Ave - Aft Sg Seletar Bridge (59019) Line Summary: Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Int (59009), Yishun Ctrl 1 - Opp Blk 932 (59669), Yishun Ctrl 2 - Lentor Ave - Opp Bullion Pk Condo (55269) Yishun Community Hosp (59619), Yishun Ave 2 - Blk 608 (59059), Yishun Ave 2 - Opp Khatib Stn (59049), Lentor Ave - Opp Countryside Est (55259) Yishun Ave 2 - Yishun Sports Hall (59039), Lentor Ave - Aft Yishun Ave 1 (59029), Lentor Ave - Aft Sg Seletar Bridge (59019), Lentor Ave -

Singapore's Abc Waters

Singapore’s ABC Waters Programme 活力,美丽,清洁的新加坡水环境计划 SINGAPORE’S ABC WATERS THE BLUE MAP OF SINGAPORE 新加坡的蓝图 17 reservoirs 水库 32 rivers 河流 7,000 km of waterways and drains 公里的水路与排水 ABC WATERS PROGRAMME ABC 水域计划 Launched in 2006 2006 ACTIVE 活力的 BEAUTIFUL 美丽的 CLEAN 清洁的 New Recreational Spaces Integration of waters Improved Water Quality 新休闲空间 with urban landscape 改进水体水质 水与城市景观一体化 Typical concrete waterways 典型混凝土排水水路 Copyright © Centre for Liveable Cities Early attempts at beautifying waterbodies 美化水体的早期尝试 Sungei Api Api 阿比阿比河 Pang Sua Pond 榜耍塘 Copyright © Centre for Liveable Cities ABC WATERS PROJECTS ABC 水域项目 SUNGEI API API AND SUNGEI TAMPINES KALLANG RIVER (POTONG PASIR) – ROCHOR CANAL SUNGEI PUNGGOL Source: PUB, Singapore’s water agency ABC Waters @ Bishan Ang Mo Kio Park Before 整治前 ABC Waters @ Bishan Ang Mo Kio Park Completed 2012 整治后 2012 Integrating the design with the surroundings 设计与环 境相结合 Meditative atmosphere: Proximity to Lower serene zone Dog run, bicycle and skates Peirce Reservoir: rental in the old Bishan tranquil and quiet link Park: active recreation to the Central zone Catchment Nature Ponds in the old Reserve Bishan Park: improved and integrated with the cleansing biotope Pond Gardens River Plains 河道平原 水塘花园 Availability of space allows for the river to boldly meander into the park Source: PUB, Singapore’s water agency ABC Waters @ Kallang River – Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park Soil bioengineering techniques Rip Rap w/ Cuttings 其他植被 Gabion Wall 石笼网墙 Reed Roll 芦苇 Reed Roll 芦苇 KALLANG RIVER @ BISHAN-ANG MO KIO PARK 石笼网,植被层,木框架挡土墙 -

Participating Merchants

PARTICIPATING MERCHANTS PARTICIPATING POSTAL ADDRESS MERCHANTS CODE 460 ALEXANDRA ROAD, #01-17 AND #01-20 119963 53 ANG MO KIO AVENUE 3, #01-40 AMK HUB 569933 241/243 VICTORIA STREET, BUGIS VILLAGE 188030 BUKIT PANJANG PLAZA, #01-28 1 JELEBU ROAD 677743 175 BENCOOLEN STREET, #01-01 BURLINGTON SQUARE 189649 THE CENTRAL 6 EU TONG SEN STREET, #01-23 TO 26 059817 2 CHANGI BUSINESS PARK AVENUE 1, #01-05 486015 1 SENG KANG SQUARE, #B1-14/14A COMPASS ONE 545078 FAIRPRICE HUB 1 JOO KOON CIRCLE, #01-51 629117 FUCHUN COMMUNITY CLUB, #01-01 NO 1 WOODLANDS STREET 31 738581 11 BEDOK NORTH STREET 1, #01-33 469662 4 HILLVIEW RISE, #01-06 #01-07 HILLV2 667979 INCOME AT RAFFLES 16 COLLYER QUAY, #01-01/02 049318 2 JURONG EAST STREET 21, #01-51 609601 50 JURONG GATEWAY ROAD JEM, #B1-02 608549 78 AIRPORT BOULEVARD, #B2-235-236 JEWEL CHANGI AIRPORT 819666 63 JURONG WEST CENTRAL 3, #B1-54/55 JURONG POINT SHOPPING CENTRE 648331 KALLANG LEISURE PARK 5 STADIUM WALK, #01-43 397693 216 ANG MO KIO AVE 4, #01-01 569897 1 LOWER KENT RIDGE ROAD, #03-11 ONE KENT RIDGE 119082 BLK 809 FRENCH ROAD, #01-31 KITCHENER COMPLEX 200809 Burger King BLK 258 PASIR RIS STREET 21, #01-23 510258 8A MARINA BOULEVARD, #B2-03 MARINA BAY LINK MALL 018984 BLK 4 WOODLANDS STREET 12, #02-01 738623 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL NEX, #B1-30/31 556083 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD, #01-11 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 120 PASIR RIS CENTRAL, #01-11 PASIR RIS SPORTS CENTRE 519640 60 PAYA LEBAR ROAD, #01-40/41/42/43 409051 PLAZA SINGAPURA 68 ORCHARD ROAD, #B1-11 238839 33 SENGKANG WEST AVENUE, #01-09/10/11/12/13/14 THE -

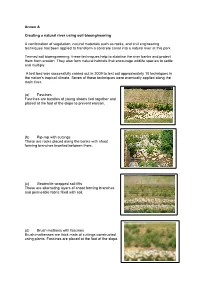

Annex a Creating a Natural River Using Soil Bioengineering

Annex A Creating a natural river using soil bioengineering A combination of vegetation, natural materials such as rocks, and civil engineering techniques has been applied to transform a concrete canal into a natural river at this park. Termed soil bioengineering, these techniques help to stabilise the river banks and protect them from erosion. They also form natural habitats that encourage wildlife species to settle and multiply. A test bed was successfully carried out in 2009 to test out approximately 10 techniques in the nation’s tropical climate. Seven of these techniques were eventually applied along the main river. (a) Fascines Fascines are bundles of young shoots tied together and placed at the foot of the slope to prevent erosion. (b) Rip-rap with cuttings These are rocks placed along the banks with shoot forming branches inserted between them. (c) Geotextile wrapped soil-lifts These are alternating layers of shoot forming branches and permeable fabric filled with soil. (d) Brush mattress with fascines Brush mattresses are thick mats of cuttings constructed using plants. Fascines are placed at the foot of the slope. (e) Reed rolls These are geotextile fabrics that are planted with vegetation and soil and secured using wood stakes. (f) Gabions These are structurally-stable steel wire baskets filled with rocks. They are stacked on top of one another to provide instant erosion control and river bank protection. (g) Geotextile with plantings Commonly used for erosion control purposes, plantings are covered by a permeable fabric. These are applied further inland. Annex B Safety comes first A river monitoring and warning system with water level sensors, warning lights, sirens and audio announcements are in place to provide early warning in the event of impending heavy rain or rising water levels. -

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange

Participating Merchants Address Postal Code Club21 3.1 Phillip Lim 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 A|X Armani Exchange 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 391 Orchard Road, #B1-03/04 Ngee Ann City 238872 290 Orchard Rd, 02-13/14-16 Paragon #02-17/19 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, B2-15/16/16A The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Armani Junior 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-62 018972 Bao Bao Issey Miyake 2 Orchard Turn, ION Orchard #03-24 238801 Bonpoint 583 Orchard Road, #02-11/12/13 Forum The Shopping Mall 238884 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-61 018972 CK Calvin Klein 2 Orchard Turn, 03-09 ION Orchard 238801 290 Orchard Road, 02-33/34 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-17A 018972 Club21 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 Men 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Club21 X Play Comme 2 Bayfront Avenue, #B1-68 The Shoppes At Marina Bay Sands 018972 Des Garscons 2 Orchard Turn, #03-10 ION Orchard 238801 Comme Des Garcons 6B Orange Grove Road, Level 1 Como House 258332 Pocket Commes des Garcons 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 DKNY 290 Orchard Rd, 02-43 Paragon 238859 2 Orchard Turn, B1-03 ION Orchard 238801 Dries Van Noten 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Emporio Armani 290 Orchard Road, 01-23/24 Paragon 238859 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-16 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 Giorgio Armani 2 Bayfront Avenue, B1-76/77 The Shoppes at Marina Bay Sands 018972 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Issey Miyake 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Marni 581 Orchard Road, Hilton Hotel 238883 Mulberry 2 Bayfront Avenue, 01-41/42 018972 -

One Party Dominance Survival: the Case of Singapore and Taiwan

One Party Dominance Survival: The Case of Singapore and Taiwan DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Lan Hu Graduate Program in Political Science The Ohio State University 2011 Dissertation Committee: Professor R. William Liddle Professor Jeremy Wallace Professor Marcus Kurtz Copyrighted by Lan Hu 2011 Abstract Can a one-party-dominant authoritarian regime survive in a modernized society? Why is it that some survive while others fail? Singapore and Taiwan provide comparable cases to partially explain this puzzle. Both countries share many similar cultural and developmental backgrounds. One-party dominance in Taiwan failed in the 1980s when Taiwan became modern. But in Singapore, the one-party regime survived the opposition’s challenges in the 1960s and has remained stable since then. There are few comparative studies of these two countries. Through empirical studies of the two cases, I conclude that regime structure, i.e., clientelistic versus professional structure, affects the chances of authoritarian survival after the society becomes modern. This conclusion is derived from a two-country comparative study. Further research is necessary to test if the same conclusion can be applied to other cases. This research contributes to the understanding of one-party-dominant regimes in modernizing societies. ii Dedication Dedicated to the Lord, Jesus Christ. “Counsel and sound judgment are mine; I have insight, I have power. By Me kings reign and rulers issue decrees that are just; by Me princes govern, and nobles—all who rule on earth.” Proverbs 8:14-16 iii Acknowledgments I thank my committee members Professor R. -

13 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

13 bus time schedule & line map 13 Upp East Coast Ter View In Website Mode The 13 bus line (Upp East Coast Ter) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Upp East Coast Ter: 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM (2) Yio Chu Kang Int: 5:30 AM - 11:09 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 13 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 13 bus arriving. Direction: Upp East Coast Ter 13 bus Time Schedule 64 stops Upp East Coast Ter Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:45 AM - 11:29 PM Monday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 - Yio Chu Kang Int (55509) Tuesday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Opp Blk 646 (55209) Wednesday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Bef Ang Mo Kio Lib (54059) Thursday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Courts Ang Mo Kio (54049) Friday 5:35 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6, Singapore Saturday 5:45 AM - 11:29 PM Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Bef Al-Muttaqin Mque (54039) 5140 Ang Mo Kio Avenue 6, Singapore Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Blk 307a (54019) 307A Ang Mo Kio Avenue 1, Singapore 13 bus Info Direction: Upp East Coast Ter Marymount Rd - Blk 254 (53169) Stops: 64 Trip Duration: 99 min Bishan St 22 - Blk 245 (53379) Line Summary: Ang Mo Kio Ave 8 - Yio Chu Kang Int 245 Bishan Street 22, Singapore (55509), Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Opp Blk 646 (55209), Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Bef Ang Mo Kio Lib (54059), Ang Bishan St 22 - Opp Bishan Nth Shop Mall (53389) Mo Kio Ave 6 - Courts Ang Mo Kio (54049), Ang Mo 230 Bishan Street 23, Singapore Kio Ave 6 - Bef Al-Muttaqin Mque (54039), Ang Mo Kio Ave 6 - Blk 307a (54019), Marymount -

1 Participating Merchants Address/Website Postal Code

PARTICIPATING ADDRESS/WEBSITE POSTAL MERCHANTS CODE 430 UPPER CHANGI ROAD #01-47/48/49 EAST VILLAGE 487048 16 ENG GOR STREET #01-05/08 79717 12 KALLANG AVENUE APERIA #01/51 339511 442, ORCHARD ROAD B1-01-11 238879 896 DUNEARM ROAD #02-01 SIME DARBY CENTRAL 589472 1 SENGKANG SQUARE #B1-25 COMPASS ONE 545078 176 ORCHARD ROAD #B1-09/10 CENTRE POINT 238843 21 TAMPINES NORTH DRIVE 2 #03-01 528765 5 STRAITS VIEW #B2-15/16, MARINA ONE, THE HEART 18935 41 SUNSET WAY #01-01A CLEMENTI ARCADE 597071 1 FUSIONOPOLIS WAY #B2-03 CONNEXIS 138632 101 THOMSON ROAD #B1-52 307591 NO 238 THOMSON ROAD #01-28/29 307683 293 HOLLAND ROAD #01-01 JELITA SHOPPING CENTRE 278628 211 HOLLAND AVENUE #01-02,04,05 HOLLAND 278967 SHOPPING CTR 154 WEST COAST ROAD B1-19, WEST COAST PLAZA 127371 501 BUKIT TIMAH ROAD CLUNY COURT #01-02 259760 80 MARINE PARADE ROAD #B1-84 PARKWAY PARADE 449269 5 STADIUM WALK #B1-01/05 LEISURE PARK 397693 10 TAMPINES CENTRAL 1 TAMPINES 1 #B1-01/02 529536 464-486 JALAN ASAS UPPER BUKIT TIMAH ROAD 678077 NO 1 WOODLANDS SQUARE #B1-31/32/33 CAUSEWAY COLD STORAGE 738099 POINT 1 MARITIME SQUARE #01-48 TO 50 99253 20 GREENWOOD AVE 289215 930 YISHUN AVENUE 2 #B1-11 TO 16 NORTHPOINT 769098 SHOPPING CENTRE 383 BUKIT TIMAH RD #01-09A ALOCASSIA APARTMENT 259727 23 SERANGOON CENTRAL #B2-44/45 NEX 556083 1 SELETAR ROAD #01-11 GREENWICH V 807011 1 COVE AVENUE SENTOSA ARRIVAL PLAZA #02-07/10 98537 101 CLEMENTI ROAD #01-01 KENT VALE ESTATE 179787 1 VISTA EXCHANGE GREEN #B1-02 & 35/36 THE STAR 138617 VISTA 2 FIRST STREET #01-05/06/12/13/14/15/16 SIGLAP V 458278