The Transmission of Irish Law in the Fourteenth and Sixteenth Centuries: Exploring the Social and Historical Contexts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Brief History of the Purcells of Ireland

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND TABLE OF CONTENTS Part One: The Purcells as lieutenants and kinsmen of the Butler Family of Ormond – page 4 Part Two: The history of the senior line, the Purcells of Loughmoe, as an illustration of the evolving fortunes of the family over the centuries – page 9 1100s to 1300s – page 9 1400s and 1500s – page 25 1600s and 1700s – page 33 Part Three: An account of several junior lines of the Purcells of Loughmoe – page 43 The Purcells of Fennel and Ballyfoyle – page 44 The Purcells of Foulksrath – page 47 The Purcells of the Garrans – page 49 The Purcells of Conahy – page 50 The final collapse of the Purcells – page 54 APPENDIX I: THE TITLES OF BARON HELD BY THE PURCELLS – page 68 APPENDIX II: CHIEF SEATS OF SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 75 APPENDIX III: COATS OF ARMS OF VARIOUS BRANCHES OF THE PURCELL FAMILY – page 78 APPENDIX IV: FOUR ANCIENT PEDIGREES OF THE BARONS OF LOUGHMOE – page 82 Revision of 18 May 2020 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE PURCELLS OF IRELAND1 Brien Purcell Horan2 Copyright 2020 For centuries, the Purcells in Ireland were principally a military family, although they also played a role in the governmental and ecclesiastical life of that country. Theirs were, with some exceptions, supporting rather than leading roles. In the feudal period, they were knights, not earls. Afterwards, with occasional exceptions such as Major General Patrick Purcell, who died fighting Cromwell,3 they tended to be colonels and captains rather than generals. They served as sheriffs and seneschals rather than Irish viceroys or lords deputy. -

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, C

The Reform Treatises and Discourse of Early Tudor Ireland, c. 1515‐1541 by Chad T. Marshall BA (Hons., Archaeology, Toronto), MA (History and Classics, Tasmania) School of Humanities Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy University of Tasmania, December, 2018 Declaration of Originality This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for a degree or diploma by the University or any other institution, except by way of background information and duly acknowledged in the thesis, and to the best of my knowledge and belief no material previously published or written by another person except where due acknowledgement is made in the text of the thesis, nor does the thesis contain any material that infringes copyright. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 i Authority of Access This thesis may be made available for loan and limited copying and communication in accordance with the Copyright Act 1968. Signed: _________________________ Date: 7/12/2018 ii Acknowledgements This thesis is for my wife, Elizabeth van der Geest, a woman of boundless beauty, talent, and mystery, who continuously demonstrates an inestimable ability to elevate the spirit, of which an equal part is given over to mastery of that other vital craft which serves to refine its expression. I extend particular gratitude to my supervisors: Drs. Gavin Daly and Michael Bennett. They permitted me the scope to explore the arena of Late Medieval and Early Modern Ireland and England, and skilfully trained wide‐ranging interests onto a workable topic and – testifying to their miraculous abilities – a completed thesis. Thanks, too, to Peter Crooks of Trinity College Dublin and David Heffernan of Queen’s University Belfast for early advice. -

Etymology of the Principal Gaelic National Names

^^t^Jf/-^ '^^ OUTLINES GAELIC ETYMOLOGY BY THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, Stirwng f ETYMOLOGY OF THK PRINCIPAL GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES |'( I WHICH IS ADDED A DISQUISITION ON PTOLEMY'S GEOGRAPHY OF SCOTLAND B V THE LATE ALEXANDER MACBAIN, M.A., LL.D. ENEAS MACKAY, STIRLING 1911 PRINTKD AT THE " NORTHERN OHRONIOLB " OFFICE, INYBRNESS PREFACE The following Etymology of the Principal Gaelic ISTational Names, Personal Names, and Surnames was originally, and still is, part of the Gaelic EtymologicaJ Dictionary by the late Dr MacBain. The Disquisition on Ptolemy's Geography of Scotland first appeared in the Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, and, later, as a pamphlet. The Publisher feels sure that the issue of these Treatises in their present foim will confer a boon on those who cannot have access to them as originally published. They contain a great deal of information on subjects which have for long years interested Gaelic students and the Gaelic public, although they have not always properly understood them. Indeed, hereto- fore they have been much obscured by fanciful fallacies, which Dr MacBain's study and exposition will go a long way to dispel. ETYMOLOGY OF THE PRINCIPAI, GAELIC NATIONAL NAMES PERSONAL NAMES AND SURNAMES ; NATIONAL NAMES Albion, Great Britain in the Greek writers, Gr. "AXfSiov, AX^iotv, Ptolemy's AXovlwv, Lat. Albion (Pliny), G. Alba, g. Albainn, * Scotland, Ir., E. Ir. Alba, Alban, W. Alban : Albion- (Stokes), " " white-land ; Lat. albus, white ; Gr. dA</)os, white leprosy, white (Hes.) ; 0. H. G. albiz, swan. -

Ireland and Scotland in the Later Middle Ages»

ANALES DE LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE. HISTORIA MEDIEVAL, n.º 19 (2015-2016): 153-174 DOI:10.14198/medieval.2015-2016.19.05 I.S.S.N.: 0212-2480 Puede citar este artículo como: Brown, Michael. «Realms, regions and lords: Ireland and Scotland in the later Middle Ages». Anales de la Universidad de Alicante. Historia Medieval, N. 19 (2015-2016): 153-174, DOI:10.14198/ medieval.2015-2016.19.05 REALMS, REGIONS AND LORDS: IRELAND AND SCOTLAND IN THE LATER MIDDLE AGES Michael Brown Department of Scottish History, University of St Andrews RESUMEN Los estudios sobre política de las Islas Británicas en la baja edad media han tendido a tratar sobre territorios concretos o a poner el Reino de Inglaterra en el centro de los debates. No obstante, en términos de su tamaño y carácter interno, hay buenas razones para considerar el Reino de Escocia y el Señorío de Irlanda como modelos de sociedad política. Más allá las significativas diferencias en el estatus, leyes y relaciones externas, hacia el año 1400 los dos territorios pueden relacionarse por compartir experiencias comunes de gobierno y de guerras internas. Éstas son las más aparentes desde una perspectiva regional. Tanto Irlanda y Escocia operaban como sistemas políticos regionalizados en los que predominaban los intereses de las principales casas aristocráticas. La importancia de dichas casas fue reconocida tanto internamente como por el gobierno real. Observando en regiones paralelas, Munster y el nordeste de Escocia, es posible identificar rasgos comparables y diferencias de largo término en dichas sociedades. Palabras clave: Baja edad media; Escocia; Irlanda; Guerra; Gobierno. -

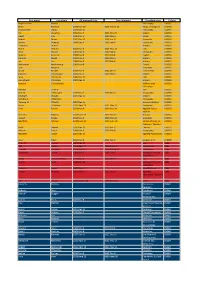

Barristers on Panel

st Report Run Date: 21 Jun 2019 BARRISTERS ON PANEL The below list contains information on the number of payments* and the total amount paid to On Panel barristers for the period 1/07/18 – 31/12/18 Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Amount Number Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of Barrister Name Payable of (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments (€) Payments Buckley, Declan 417,945 52 McGrath, Imogen 43,604 15 Binchy, Michael 11,132 8 Fitzpatrick, Andrew 3,094 6 Egan, Emily 394,952 24 Boughton, David 43,480 86 Farrelly, Aoife 10,908 13 Fitzgerald, William 2,653 11 Hanratty, Patrick 385,932 11 Fleck, Kieran 43,142 7 Delaney, Michael Patrick 10,701 2 MacMahon, Noel A. 2,583 1 Halpin, Conor 337,833 26 Gayer, Sasha Louise 39,452 4 Lydon, Eileen 10,578 2 Roberts, Conor 2,030 3 O'Braonain, Luan 231,215 17 Ramsey, Michael 37,023 1 Hand, Derry 10,376 8 Cheatle, John 1,845 1 Kavanagh, James M. 187,198 6 Fahey, Grainne 36,678 73 Scully, Lorraine 9,696 6 Maher, Jeremy 1,538 2 Foley, Brian 181,914 20 McGuinness, Donal 29,223 5 Hogan, John 9,545 7 Keleher, Daniel 1,162 1 Woulfe, Donnchadh 179,160 9 Lowe, Robert 28,226 2 Walsh, Aidan 8,979 1 Hewson, Dermot G. 1,119 1 McCrann, Oonah 159,623 18 Barrington, Eileen 27,596 2 Kilfeather, Jonathan 8,642 4 Keane, Deirdre 1,076 4 McCullough, Eoin 143,268 14 White, Rory 27,032 14 Fleming, David 8,107 2 Danaher, Gerard 954 2 Corcoran, Sarah 139,707 104 Farren, Georgina 25,227 5 Tennyson, Lauren 7,679 3 Cullinane, Padraig J. -

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/Area

First Name Last Name GB Approval Date Date Informed Discipline/area College Roger Garrett Barden Philosophy CACSSS Brian Bocking 2015 Nov 15 2016 March 14 Study of Religions CACSSS Desmond M Clarke 2007 Dec 11 Philosophy CACSSS Pat Coughlan 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 English CACSSS David Cox 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Music CACSSS Robert Devoy 2011 Dec 13 2012 Jan 11 Geograhy CACSSS Francis Douglas 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Thomas J Dunne History CACSSS Maire Herbert 2013 Nov 5 2013 Nov 15 Irish CACSSS Aine Hyland 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 Education CACSSS Colbert Kearney 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 English CACSSS Dermot Keogh 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 History CACSSS Joe Lee 2009 Dec 8 2010 Feb 8 History CACSSS Mathew M MacNamara 2005 Nov 8 French CACSSS John Maguire Sociology CACSSS Grace Neville 2012 Nov 6 2012 Dec 6 French/T&L CACSSS Eamonn O Carragain 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 English CACSSS Sean O Coileain 2006 Dec 12 Irish CACSSS Donnchadh O Corrain 2007 Dec 11 History CACSSS Gearóid Ó Crualaoich Folklore and CACSSS Ethnology Padraig O Riain irish CACSSS Patrick O'Flanagan 2010 Nov 2 2010 Nov 5 Geography CACSSS Elisabeth Okasha 2007 Dec 11 English CACSSS Brendan E O'Mahony Philosophy CACSSS Terence W O'Reilly 2007 Dec 11 Hispanic Studies CACSSS Denis O'Sullivan 2011 April 19 2011 May 11 Education CACSSS Fred Powell 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Applied Social CACSSS Studies Geoffrey Roberts 2017 June 13 2017 Dec 01 History CACSSS Joseph Ruane 2014 Nov 4 2014 Nov 24 Sociology CACSSS Manfred Schewe 2019 June 11 2019 June 18 School of Lang, Lit, CACSSS -

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard)

Written Answers to Questions Official Report (Hansard) Friday 29 June 2012 Volume 76, No WA2 This publication contains the written answers to questions tabled by Members. The content of the responses is as received at the time from the relevant Minister or representative of the Assembly Commission and has not been subject to the official reporting process or changed in any way. Contents Written Answers to Questions Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister ............................................................... WA 193 Department of Agriculture and Rural Development .................................................................. WA 195 Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure ................................................................................ WA 199 Department of Education ...................................................................................................... WA 204 Department for Employment and Learning .............................................................................. WA 219 Department of Enterprise, Trade and Investment .................................................................... WA 222 Department of the Environment ............................................................................................. WA 222 Department of Finance and Personnel ................................................................................... WA 244 Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety ......................................................... WA 253 Department -

Women and Slavery in the Early Irish Laws

Women and Slavery in the Early Irish Laws Charlene M. Eska Abstract: As stated by Fergus Kelly (Early Irish Farming, 438), the numerous ‘references to slavery in law-tracts, wisdom-texts, saints’ Lives, annals, and sagas’ attest to the ‘considerable importance [of slavery] in early Irish Society’. Yet, despite these numerous references to slavery, only a handful of scholars to date have undertaken the task of researching this subject: Paul Holm has analyzed the slave trade of Dublin; Niall Brady has looked at labor and agriculture; and Fergus Kelly has described slavery in general and slave labor as represented by the early Irish law-tracts. This paper builds upon the work of previous scholars and, in particular, focuses on women and slavery as represented in the early Irish laws. This paper will discuss, from a legal standpoint, the specific law-tracts in which women and slavery are mentioned, the legal contexts of such references, and possible interpretations of the material. For scholars of medieval Ireland, it is common knowledge that slaves formed an important part of the economy and the labor force in any wealthy household.1 Fergus Kelly has remarked that the numerous ‘references to slavery in law- tracts, wisdom-texts, saints’ Lives, annals, and sagas’ attest to the ‘considerable importance [of slavery] in early Irish society’ (1998, 438). Yet, despite these numerous references to slavery, only a handful of scholars to date have undertaken research on the subject, among whom are Paul Holm, who has analyzed the slave trade of Dublin (1986); Niall Brady, who has looked at labor and agriculture (1994); and Fergus Kelly, who has described slavery in general and slave labor as represented in the early Irish law-tracts (1988, 95–98 and 1998, 438–42). -

Legal Translation and Terminology in the Irish Free State, 1922-1937

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Legal Translation and Terminology in the Irish Free State, 1922-1937 McGrory, Orla Award date: 2018 Awarding institution: Queen's University Belfast Link to publication Terms of use All those accessing thesis content in Queen’s University Belfast Research Portal are subject to the following terms and conditions of use • Copyright is subject to the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1988, or as modified by any successor legislation • Copyright and moral rights for thesis content are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners • A copy of a thesis may be downloaded for personal non-commercial research/study without the need for permission or charge • Distribution or reproduction of thesis content in any format is not permitted without the permission of the copyright holder • When citing this work, full bibliographic details should be supplied, including the author, title, awarding institution and date of thesis Take down policy A thesis can be removed from the Research Portal if there has been a breach of copyright, or a similarly robust reason. If you believe this document breaches copyright, or there is sufficient cause to take down, please contact us, citing details. Email: [email protected] Supplementary materials Where possible, we endeavour to provide supplementary materials to theses. This may include video, audio and other types of files. We endeavour to capture all content and upload as part of the Pure record for each thesis. Note, it may not be possible in all instances to convert analogue formats to usable digital formats for some supplementary materials. We exercise best efforts on our behalf and, in such instances, encourage the individual to consult the physical thesis for further information. -

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge

Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge David Noel Wilson, B.A. Hon., Grad. Dip. Data Processing, Grad. Dip. History. Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Masters of Arts (with Advanced Seminars component) in the Department of History, Faculty of Arts, University of Melbourne. July, 2004 © David N. Wilson 1 Abstract David Noel Wilson, Honour and Early Irish Society: a Study of the Táin Bó Cúalnge. This is a study of an early Irish heroic tale, the Táin Bó Cúailnge (The Cattle Raid of the Cooley). It examines the role and function of honour, both within the tale and within the society that produced the text. Its demonstrates how the pursuit of honour has influenced both the theme and structure of the Táin . Questions about honour and about the resolution of conflicting obligations form the subject matter of many of the heroic tales. The rewards and punishments of honour and shame are the primary mechanism of social control in societies without organised instruments of social coercion, such as a police force: these societies can be defined as being ‘honour-based’. Early Ireland was an honour- based society. This study proposes that, in honour-based societies, to act honourably was to act with ‘appropriate and balanced reciprocity’. Applying this understanding to the analysis of the Táin suggests a new approach to the reading the tale. This approach explains how the seemingly repetitive accounts of Cú Chulainn in single combat, which some scholars have found wearisome, serve to maximise his honour as a warrior in the eyes of the audience of the tale. -

Order of Celtic Wolves Lesson 6

ORDER OF CELTIC WOLVES LESSON 6 Introduction Welcome to the sixth lesson. What a fantastic achievement making it so far. If you are enjoying the lessons let like-minded friends know. In this lesson, we are looking at the diet, clothing, and appearance of the Celts. We are also going to look at the complex social structure of the wolves and dispel some common notions about Alpha, Beta and Omega wolves. In the Bards section we look at the tales associated with Lugh. We will look at the role of Vates as healers, the herbal medicinal gardens and some ancient remedies that still work today. Finally, we finish the lesson with an overview of the Brehon Law of the Druids. I hope that there is something in the lesson that appeals to you. Sometimes head knowledge is great for General Knowledge quizzes, but the best way to learn is to get involved. Try some of the ancient remedies, eat some of the recipes, draw principles from the social structure of wolves and Brehon law and you may even want to dress and wear your hair like a Celt. Blessings to you all. Filtiarn Celts The Celtic Diet Athenaeus was an ethnic Greek and seems to have been a native of Naucrautis, Egypt. Although the dates of his birth and death have been lost, he seems to have been active in the late second and early third centuries of the common era. His surviving work The Deipnosophists (Dinner-table Philosophers) is a fifteen-volume text focusing on dining customs and surrounding rituals. -

1926 Census County Fermanagh Report

GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND CENSUS OF NORTHERN IRELAND 1926 COUNTY OF FERMANAGH. Printed and presented pursuant to the provisions of 15 and 16 Geo. V., ch. 21 BELFAST: PUBLISHED BY H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE ON BEHALF OF THE GOVERNMENT OF NORTHERN IRELAND. To be purchased directly from H. M. Stationery Office at the following addresses: 15 DONEGALL SQUARE WEST, BELFAST: 120 GEORGE ST., EDINBURGH ; YORK ST., MANCHESTER ; 1 ST. ANDREW'S CRESCENT, CARDIFF ; AD ASTRAL HOUSE, KINGSWAY, LONDON, W.C.2; OR THROUGH ANY BOOKSELLER. 1928 Price 5s. Od. net THE. QUEEN'S UNIVERSITY OF BELFAST. iii. PREFACE. This volume has been prepared in accordance with the prov1s1ons of Section 6 (1) of the Census Act (Northern Ireland), 1925. The 1926 Census statistics which it contains were compiled from the returns made as at midnight of the 18-19th April, 1926 : they supersede those in the Preliminary Report published in August, 1926, and may be regarded as final. The Census· publications will consist of:-· 1. SEVEN CouNTY VoLUMES, each similar in design and scope to the present publication. 2. A GENERAL REPORT relating to Northern Ireland as a whole, covering in more detail the. statistics shown in the County Volumes, and containing in addition tables showing (i.) the occupational distribution of persons engaged in each of 51 groups of industries; (ii.) the distribution of the foreign born population by nationality, age, marital condition, and occupation; (iii.) the distribution of families of dependent children under 16 · years of age, by age, sex, marital condition, and occupation of parent; (iv.) the occupational distribution of persons suffering frominfirmities.