Diagnostic Pathology of Tumors of Peripheral Nerve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF2)

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF2) and the Implications for Vestibular Schwannoma and Meningioma Pathogenesis Suha Bachir 1,† , Sanjit Shah 2,† , Scott Shapiro 3,†, Abigail Koehler 4, Abdelkader Mahammedi 5 , Ravi N. Samy 3, Mario Zuccarello 2, Elizabeth Schorry 1 and Soma Sengupta 4,* 1 Department of Genetics, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, Cincinnati, OH 45229, USA; [email protected] (S.B.); [email protected] (E.S.) 2 Department of Neurosurgery, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (M.Z.) 3 Department of Otolaryngology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA; [email protected] (S.S.); [email protected] (R.N.S.) 4 Department of Neurology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA; [email protected] 5 Department of Radiology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH 45267, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally. Abstract: Patients diagnosed with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) are extremely likely to develop meningiomas, in addition to vestibular schwannomas. Meningiomas are a common primary brain tumor; many NF2 patients suffer from multiple meningiomas. In NF2, patients have mutations in the NF2 gene, specifically with loss of function in a tumor-suppressor protein that has a number of synonymous names, including: Merlin, Neurofibromin 2, and schwannomin. Merlin is a 70 kDa protein that has 10 different isoforms. The Hippo Tumor Suppressor pathway is regulated upstream by Merlin. This pathway is critical in regulating cell proliferation and apoptosis, characteristics that are important for tumor progression. -

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST): an Overview with Emphasis on Pathology, Imaging and Management Strategies

Thomas Jefferson University Jefferson Digital Commons Department of Neurosurgery Faculty Papers Department of Neurosurgery 6-2012 Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST): An overview with emphasis on pathology, imaging and management strategies Timothy C. Beer 3rd year medical student, Jefferson Medical College Follow this and additional works at: https://jdc.jefferson.edu/neurosurgeryfp Part of the Medical Neurobiology Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Recommended Citation Beer, Timothy C., "Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor (MPNST): An overview with emphasis on pathology, imaging and management strategies" (2012). Department of Neurosurgery Faculty Papers. Paper 18. https://jdc.jefferson.edu/neurosurgeryfp/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jefferson Digital Commons. The Jefferson Digital Commons is a service of Thomas Jefferson University's Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL). The Commons is a showcase for Jefferson books and journals, peer-reviewed scholarly publications, unique historical collections from the University archives, and teaching tools. The Jefferson Digital Commons allows researchers and interested readers anywhere in the world to learn about and keep up to date with Jefferson scholarship. This article has been accepted for inclusion in Department of Neurosurgery Faculty Papers by an authorized administrator of the Jefferson Digital Commons. For more information, please contact: [email protected]. An overview with emphasis -

Information About Mosaic Neurofibromatosis Type 2 (NF2)

Information about mosaic Neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2) NF2 occurs because of a mutation (change) in the NF2 gene. When this change is present at the time of conception the changed gene will be present in all the cells of the baby. When this mutation occurs later in the development of the forming embryo, the baby will go on to have a mix of cells: some with the “normal” genetic information and some with the changed information. This mix of cells is called mosaicism. Approximately half the people who have a diagnosis of NF2 have inherited the misprinted NF2 gene change from their mother or father who will also have NF2. They will have that misprinted gene in all the cells of their body. When they have their children, there will be a 1 in 2 chance of passing on NF2 to each child they have. However about half of people with NF2 are the first person in the family to be affected. They have no family history and have not inherited the condition from a parent. When doctors studied this group of patients more closely they noticed certain characteristics. Significantly they observed that fewer children had inherited NF2 than expected some people in this group had relatively mild NF2 NF2 tumours in some patients tended to grow on one side of their body rather than both sides that when a blood sample was tested to identify the NF2 gene, the gene change could not be found in 30-40% of people This lead researchers to conclude that this group of people were most likely to be mosaic for NF2 i.e. -

Network Scan Data

CTEP Protocol No: T-99-0090 CC Protocol No: 01-C-0222 Amendment: J Revised: 4/21/09 IRB Approval Date: A Phase II Randomized, Cross-Over, Double-Blinded, Placebo-Controlled Trial of the Farnesyltransferase Inhibitor R115777 in Pediatric Patients with Neurofibromatosis Type 1 and Progressive Plexiform Neurofibromas Coordinating Center: Pediatric Oncology Branch, NCI Principal Investigator: Brigitte Widemann, M.D.* (POB, NCI) NIH Associate Investigators: Frank M. Balis, M.D. (POB, NCI) Beth Fox, M.D. (POB, NCI) Kathy Warren, M.D. (NOB, NCI) Andy Gillespie, R.N. (ND, CC) Eva Dombi, MD (POB, NCI)** Nalini Jayaprakash, (POB, NCI) Diane Cole, (POB, NCI) Seth Steinberg, Ph.D. (BDMB, DCS, NCI) Nicholas Patronas, M.D. (DR, CC)** Maria Tsokos, M.D., (Laboratory of Pathology, NCI)** Pamela Wolters, Ph.D. (HAMB, NCI) Staci Martin, Ph.D. (HAMB, NCI) Jeffrey Solomon, (NIH and Sensor Systems, Inc.) Non-NIH Associate Investigators: Wanda Salzer, M.D. ** Keesler Air Force Base, Biloxi, Mississippi) 81st MDOS/SGOC 301 Fisher Street, Room 1A132 Keesler AFB, MS 39534-2519 Phone: 228-377-6524 E-mail: [email protected] Bruce R. Korf, M.D., Ph.D. ** Chair, Department of Genetics Univeristy of Alabama at Birmingham 1530 3rd Ave. S. Birmingham, AL 35294 Phone: (205)-934-9411, Fax: (205)-934-9488 E-mail: [email protected] David H. Gutmann, M.D., Ph.D. ** Department of Neurology Washington University School of Medicine St. Louis Children’s Hospital Box 8111, 660 S. Euclid Avenue St. Louis, MO 63110 Phone: (314)-632-7149, Fax: (314)-362-9462 E-mail: [email protected] 1 4/21/2009 T-99-0090, 01-C-0222 Arie Perry, M.D. -

Simultaneous Neurofibroma and Schwannoma of the Sciatic Nerve

Simultaneous Neurofibroma and Schwannoma of the Sciatic Nerve 1 4 1 1 2 3 1 S. A. Sintzoff, Jr.,I.5 W . 0. Bank, · P. A. Gevenois, C. Matos, J. Noterman, J. Flament-Durand, and J. Struyven Summary: The authors report a case of simultaneously occur MR imaging was performed on a 0.5-T system (Gyro ring neurofibroma and schwannoma of the sciatic nerve and scan T5, Philips Medical Systems, Eindhoven, The Neth discuss the complementary aspects of MR and OS. The Schwan erlands) using a wrap-around knee surface coil in order to norna was well-defined and showed distal enhancement on better define the relationships between the tumors and the sonographic evaluation, whereas the neurofibroma was ill-de nerve. Each tumor was isointense to the normal nerve on fined; both tumors were hypoechoic. Tl- and T2-weighted MR T1-weighted images and hyperintense to it on proton Images revealed similar signal characteristics of the two tumors, density and T2-weighted images (Fig. 2A-2C). After intra but Intense enhancement following administration of gadolin venous gadolinium-DTPA injection, the distal mass showed ium-DTPA distinguished the schwannoma from the neurofi intense enhancement, conserving a thin hypointense border broma. (Fig. 2D). Physical and neurologic examination, MR of the central nervous system and skeletal radiographs failed to Index terms: Nerves, sciatic; Neuroma; Schwannoma demonstrate any additional lesions, permitting the reason able exclusion of neurofibromatosis types 1 and 2. Schwannomas and neurofibromas are com Surgical exposure demonstrated the two tumors on the external popliteal nerve (Fig. 3). The distal tumor could be (1, mon peripheral nerve neoplasms 2). -

Central Nervous System Tumors General ~1% of Tumors in Adults, but ~25% of Malignancies in Children (Only 2Nd to Leukemia)

Last updated: 3/4/2021 Prepared by Kurt Schaberg Central Nervous System Tumors General ~1% of tumors in adults, but ~25% of malignancies in children (only 2nd to leukemia). Significant increase in incidence in primary brain tumors in elderly. Metastases to the brain far outnumber primary CNS tumors→ multiple cerebral tumors. One can develop a very good DDX by just location, age, and imaging. Differential Diagnosis by clinical information: Location Pediatric/Young Adult Older Adult Cerebral/ Ganglioglioma, DNET, PXA, Glioblastoma Multiforme (GBM) Supratentorial Ependymoma, AT/RT Infiltrating Astrocytoma (grades II-III), CNS Embryonal Neoplasms Oligodendroglioma, Metastases, Lymphoma, Infection Cerebellar/ PA, Medulloblastoma, Ependymoma, Metastases, Hemangioblastoma, Infratentorial/ Choroid plexus papilloma, AT/RT Choroid plexus papilloma, Subependymoma Fourth ventricle Brainstem PA, DMG Astrocytoma, Glioblastoma, DMG, Metastases Spinal cord Ependymoma, PA, DMG, MPE, Drop Ependymoma, Astrocytoma, DMG, MPE (filum), (intramedullary) metastases Paraganglioma (filum), Spinal cord Meningioma, Schwannoma, Schwannoma, Meningioma, (extramedullary) Metastases, Melanocytoma/melanoma Melanocytoma/melanoma, MPNST Spinal cord Bone tumor, Meningioma, Abscess, Herniated disk, Lymphoma, Abscess, (extradural) Vascular malformation, Metastases, Extra-axial/Dural/ Leukemia/lymphoma, Ewing Sarcoma, Meningioma, SFT, Metastases, Lymphoma, Leptomeningeal Rhabdomyosarcoma, Disseminated medulloblastoma, DLGNT, Sellar/infundibular Pituitary adenoma, Pituitary adenoma, -

To View the ESE Recommended Curriculum of Specialisation in Clinical Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism

European Society of Endocrinology Recommended Curriculum of Specialisation in Clinical Endocrinology, Diabetes and Metabolism Version 2, November 2019 Contents Endorsement ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 3 1. Diabetes mellitus .............................................................................................................................. 4 2. Lipid disorders ................................................................................................................................... 5 3. Obesity and bariatric endocrinology ................................................................................................. 5 4. Pituitary ............................................................................................................................................ 5 5. Thyroid .............................................................................................................................................. 6 6. Parathyroid, calcium and bone ......................................................................................................... 7 7. Adrenal ............................................................................................................................................. 8 8. Reproductive endocrinology and sexual function -

RD-Action Matchmaker – Summary of Disease Expertise Recorded Under

Summary of disease expertise recorded via RD-ACTION Matchmaker under each Thematic Grouping and EURORDIS Members’ Thematic Grouping Thematic Reported expertise of those completing the EURORDIS Member perspectives on Grouping matchmaker under each heading Grouping RD Thematically Rare Bone Achondroplasia/Hypochondroplasia Achondroplasia Amelia skeletal dysplasia’s including Achondroplasia/Growth hormone cleidocranial dysostosis, arthrogryposis deficiency/MPS/Turner Brachydactyly chondrodysplasia punctate Fibrous dysplasia of bone Collagenopathy and oncologic disease such as Fibrodysplasia ossificans progressive Li-Fraumeni syndrome Osteogenesis imperfecta Congenital hand and fore-foot conditions Sterno Costo Clavicular Hyperostosis Disorders of Sex Development Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Ehlers –Danlos syndrome Fibrodysplasia Ossificans Progressiva Growth disorders Hypoparathyroidism Hypophosphatemic rickets & Nutritional Rickets Hypophosphatasia Jeune’s syndrome Limb reduction defects Madelung disease Metabolic Osteoporosis Multiple Hereditary Exostoses Osteogenesis imperfecta Osteoporosis Paediatric Osteoporosis Paget’s disease Phocomelia Pseudohypoparathyroidism Radial dysplasia Skeletal dysplasia Thanatophoric dwarfism Ulna dysplasia Rare Cancer and Adrenocortical tumours Acute monoblastic leukaemia Tumours Carcinoid tumours Brain tumour Craniopharyngioma Colon cancer, familial nonpolyposis Embryonal tumours of CNS Craniopharyngioma Ependymoma Desmoid disease Epithelial thymic tumours in -

Revision of Diagnostic Criteria for Neurofibromatosis

Revision of Diagnostic Criteria for Neurofibromatosis Gareth Evans, MD, St. Mary’s Hospital/University of Manchester, UK Susan Huson, MD, Consultant Geneticist, UK Eric Legius, MD, PhD, University of Leuven, Belgium Ludwine Messiaen, PhD, University of AlaBama, Birmingham, USA Scott Plotkin, MD, PhD, Massachusetts General Hospital, USA Pierre Wolkenstein, MD, PhD, Hôpital Henri-Mondor, France 2019 NF Conference San Francisco, CA September 21, 2019 Revision of the Diagnostic Criteria of the Neurofibromatoses 92 medical specialists 20 countries 5 continents We want your feedback! Send email to: [email protected] Participants in revision process: Leadership team Clinical Epidemiology Health Services Research: Ophthalmology: • Gareth Evans • Nilton Rezende • Vanessa Merker • Robert Avery • Sue Huson • Catherine Cassiman • Eric Legius Clinical Genetics: Internal Medicine: Pathology: • Ludwine Messiaen • Dorothy Halliday • Luiz Oswaldo Carneiro • Karin Cunha • Scott Plotkin • Maurizio Clementi Rodrigues • Anat Stemmer-Rachamimov • Pierre Wolkenstein • Arvid Heiberg • Patrice Pancza • Joanne Ngeow Scientists: Pediatrics: • Shay Ben-Schachar • Miriam Smith • Outside Experts: • Bruce Korf • Marco Giovannini Rianne Oostenbrink • • Monique Anten • Mimi Berman • Eduard Serra Robert Listernick • Jaan Toelen • Betty Schorry • Juha Peltonen Pediatric Hematology and • Arthur Aylsworth • Gareth Evans Oncology: • Meredith Wilson • Ignacio Blanco Molecular Genetics: • Michael Fisher • Helen Hanson • Dusica Babovic-Vuksanovic •Laura Papi • Christopher -

Multiple Orbital Neurofibromas, Painful Peripheral Nerve Tumors, Distinctive

European Journal of Human Genetics (2012) 20, 618–625 & 2012 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 1018-4813/12 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Multiple orbital neurofibromas, painful peripheral nerve tumors, distinctive face and marfanoid habitus: a new syndrome D Babovic-Vuksanovic*,1, Ludwine Messiaen2, Christoph Nagel3, Hilde Brems4, Bernd Scheithauer5, Ellen Denayer4, Rong Mao6, Raf Sciot7, Karen M Janowski2, Martin U Schuhmann3, Kathleen Claes8, Eline Beert4, James A Garrity9, Robert J Spinner10, Anat Stemmer-Rachamimov11, Ralitza Gavrilova1, Frank Van Calenbergh12, Victor Mautner13 and Eric Legius4 Four unrelated patients having an unusual clinical phenotype, including multiple peripheral nerve sheath tumors, are reported. Their clinical features were not typical of any known familial tumor syndrome. The patients had multiple painful neurofibromas, including bilateral orbital plexiform neurofibromas, and spinal as well as mucosal neurofibromas. In addition, they exhibited a marfanoid habitus, shared similar facial features, and had enlarged corneal nerves as well as neuronal migration defects. Comprehensive NF1, NF2 and SMARCB1 mutation analyses revealed no mutation in blood lymphocytes and in schwann cells cultured from plexiform neurofibromas. Furthermore, no mutations in RET, PRKAR1A, PTEN and other RAS-pathway genes were found in blood leukocytes. Collectively, the clinical and pathological findings in these four cases fit no known syndrome and likely represent a new disorder. European Journal of Human Genetics (2012) 20, 618–625; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.275; published online 18 January 2012 Keywords: orbital neurofibroma; plexiform neurofibroma; enlarged corneal nerves; marfanoid habitus INTRODUCTION Ruvalcaba syndrome, a part of the PHTS spectrum, develop cafe´- Peripheral nerve sheath tumors, specifically neurofibromas and au-lait spots and macules of the glans penis. -

Depo-Provera

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH INCLUDING PATIENT MEDICATION INFORMATION PR ® DEPO-PROVERA medroxyprogesterone acetate injectable suspension, USP Sterile Aqueous Suspension 50 mg/mL and 150 mg/mL Progestogen Pfizer Canada Inc. Date of Revision: 17,300 Trans-Canada Highway February 13, 2018 Kirkland, Quebec H9J 2M5 Submission Control No: 210121 ® Pharmacia & Upjohn Company LLC Pfizer Canada Inc., Licensee © Pfizer Canada Inc., 2018 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION......................................................... 3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ........................................................................ 3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE .............................................................................. 3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ................................................................................................... 4 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS: ................................................................................ 5 ADVERSE REACTIONS ................................................................................................. 18 DRUG INTERACTIONS .................................................................................................. 27 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION .............................................................................. 28 OVERDOSAGE ................................................................................................................ 30 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ............................................................ 30 STORAGE AND -

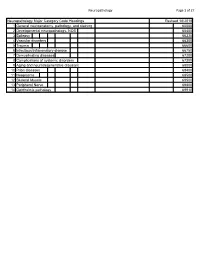

Neuropathology Category Code List

Neuropathology Page 1 of 27 Neuropathology Major Category Code Headings Revised 10/2018 1 General neuroanatomy, pathology, and staining 65000 2 Developmental neuropathology, NOS 65400 3 Epilepsy 66230 4 Vascular disorders 66300 5 Trauma 66600 6 Infectious/inflammatory disease 66750 7 Demyelinating diseases 67200 8 Complications of systemic disorders 67300 9 Aging and neurodegenerative diseases 68000 10 Prion diseases 68400 11 Neoplasms 68500 12 Skeletal Muscle 69500 13 Peripheral Nerve 69800 14 Ophthalmic pathology 69910 Neuropathology Page 2 of 27 Neuropathology 1 General neuroanatomy, pathology, and staining 65000 A Neuroanatomy, NOS 65010 1 Neocortex 65011 2 White matter 65012 3 Entorhinal cortex/hippocampus 65013 4 Deep (basal) nuclei 65014 5 Brain stem 65015 6 Cerebellum 65016 7 Spinal cord 65017 8 Pituitary 65018 9 Pineal 65019 10 Tracts 65020 11 Vascular supply 65021 12 Notochord 65022 B Cell types 65030 1 Neurons 65031 2 Astrocytes 65032 3 Oligodendroglia 65033 4 Ependyma 65034 5 Microglia and mononuclear cells 65035 6 Choroid plexus 65036 7 Meninges 65037 8 Blood vessels 65038 C Cerebrospinal fluid 65045 D Pathologic responses in neurons and axons 65050 1 Axonal degeneration/spheroid/reaction 65051 2 Central chromatolysis 65052 3 Tract degeneration 65053 4 Swollen/ballooned neurons 65054 5 Trans-synaptic neuronal degeneration 65055 6 Olivary hypertrophy 65056 7 Acute ischemic (hypoxic) cell change 65057 8 Apoptosis 65058 9 Protein aggregation 65059 10 Protein degradation/ubiquitin pathway 65060 E Neuronal nuclear inclusions 65100