A Case for African American Reparations: the Inheritance of Racist Hierarchies and Moral Harm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chinese Privatization: Between Plan and Market

CHINESE PRIVATIZATION: BETWEEN PLAN AND MARKET LAN CAO* I INTRODUCTION Since 1978, when China adopted its open-door policy and allowed its economy to be exposed to the international market, it has adhered to what Deng Xiaoping called "socialism with Chinese characteristics."1 As a result, it has produced an economy with one of the most rapid growth rates in the world by steadfastly embarking on a developmental strategy of gradual, market-oriented measures while simultaneously remaining nominally socialistic. As I discuss in this article, this strategy of reformthe mere adoption of a market economy while retaining a socialist ownership baseshould similarly be characterized as "privatization with Chinese characteristics,"2 even though it departs markedly from the more orthodox strategy most commonly associated with the term "privatization," at least as that term has been conventionally understood in the context of emerging market or transitional economies. The Russian experience of privatization, for example, represents the more dominant and more favored approach to privatizationcertainly from the point of view of the West and its advisersand is characterized by immediate privatization of the state sector, including the swift and unequivocal transfer of assets from the publicly owned state enterprises to private hands. On the other hand, "privatization with Chinese characteristics" emphasizes not the immediate privatization of the state sector but rather the retention of the state sector with the Copyright © 2001 by Lan Cao This article is also available at http://www.law.duke.edu/journals/63LCPCao. * Professor of Law, College of William and Mary Marshall-Wythe School of Law. At the time the article was written, the author was Professor of Law at Brooklyn Law School. -

Curtailing Inherited Wealth

Michigan Law Review Volume 89 Issue 1 1990 Curtailing Inherited Wealth Mark L. Ascher University of Arizona College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Law and Society Commons, Legislation Commons, and the Taxation-Federal Estate and Gift Commons Recommended Citation Mark L. Ascher, Curtailing Inherited Wealth, 89 MICH. L. REV. 69 (1990). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol89/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CURTAILING INHERITED WEALTH Mark L. Ascher* INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • . • • • • • • . • • • • • • • • . • • . • • • • . • • • 70 I. INHERITANCE IN PRINCIPLE........................... 76 A. Inheritance as a Natural Right..................... 76 B. The Positivistic Conception of Inheritance . 77 C. Why the Positivistic Conception Prevailed . 78 D. Inheritance - Property or Garbage?................ 81 E. Constitutional Concerns . 84 II. INHERITANCE AS A MATIER OF POLICY •• • . •••••.. •••• 86 A. Society's Stake in Accumulated Wealth . 86 B. Arguments in Favor of Curtailing Inheritance . 87 1. Leveling the Playing Field . 87 2. Deficit Reduction in a Painless and Appropriate Fashion........................................ 91 3. Protecting Elective Representative Government . 93 4. Increasing Privatization in the Care of the Disabled and the Elderly . 96 5. Expanding Public Ownership of National and International Treasures . 98 6. _Increasing Lifetime Charitable Giving . 98 7. Neutralizing the Co"osive Effects of Wealth..... 99 C. Arguments Against Curtailing Inheritance. -

Privatization and Property in Biology Joan E

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Washington University St. Louis: Open Scholarship Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations Biology 6-2014 Privatization and Property in Biology Joan E. Strassmann Washington University in St Louis, [email protected] David C. Queller Washington University in St Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/bio_facpubs Part of the Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Strassmann, Joan E. and Queller, David C., "Privatization and Property in Biology" (2014). Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations. 49. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/bio_facpubs/49 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biology at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biology Faculty Publications & Presentations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Privatization and property in biology 2 3 Joan E. Strassmann & David C. Queller 4 5 Department of Biology, Campus Box 1137 6 WasHington University in St. Louis 7 One Brookings Drive 8 St. Louis MO 63130 9 10 Corresponding autHor: Joan E. Strassmann 11 phone: 01-832-978-5961 12 email: [email protected] 13 14 6191 words 1 15 ABSTRACT 16 17 Organisms evolve to control, preserve, protect and invest in their own bodies. When 18 they do likewise with external resources they privatize those resources and convert 19 tHem into tHeir own property. Property is a neglected topic in biology, though 20 examples include territories, domiciles and nest structures, food cacHing, mate 21 guarding, and the resources and partners in mutualisms. -

A Guide to Kentucky Inheritance and Estate Taxes

A Guide to Kentucky Inheritance and Estate Taxes GENERAL INFORMATION Kentucky Department of Revenue The purpose of this booklet is to help achieve the mission of the Kentucky Department of Revenue by offering general information concerning the Kentucky inheritance and estate tax. Kentucky Department of Revenue Mission Statement As part of the Finance and Administration Cabinet, the mission of the Kentucky Department of Revenue is to administer tax laws, collect revenue, and provide services in a fair, courteous, and efficient manner for the benefit of the Commonwealth and its citizens. * * * * * * * * * * * * * The Kentucky Department of Revenue does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, age, religion, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity, veteran status, genetic information or ancestry in employment or the provision of services. If you have a question concerning any information contained in this booklet, or if you have any questions pertaining to a technical issue, please contact the Financial Tax Section, Kentucky Department of Revenue, Station 61, 501 High Street, Frankfort, Kentucky 40601-2103 or (502) 564-4810. INTRODUCTION Kentucky has two death taxes. Inheritance Tax The Kentucky inheritance tax is a tax on a beneficiary’s right to receive property from a deceased person. The amount of the inheritance tax depends on the relationship of the beneficiary to the deceased person and the value of the property. Most of the time, the closer the relationship the greater the exemption and the smaller the tax rate. All property belonging to a resident of Kentucky is subject to the tax except for real estate located in another state. -

Utilitarianism and Wealth Transfer Taxation

Utilitarianism and Wealth Transfer Taxation Jennifer Bird-Pollan* This article is the third in a series examining the continued relevance and philosophical legitimacy of the United States wealth transfer tax system from within a particular philosophical perspective. The article examines the utilitarianism of John Stuart Mill and his philosophical progeny and distinguishes the philosophical approach of utilitarianism from contemporary welfare economics, primarily on the basis of the concept of “utility” in each approach. After explicating the utilitarian criteria for ethical action, the article goes on to think through what Mill’s utilitarianism says about the taxation of wealth and wealth transfers, the United States federal wealth transfer tax system as it stands today, and what structural changes might improve the system under a utilitarian framework. I. INTRODUCTION A nation’s tax laws can be seen as its manifested distributive justice ideals. While it is clear that the United States’ Tax Code contains a variety of provisions aimed at particular non-distributive justice goals,1 underneath the political * James and Mary Lassiter Associate Professor of Law, University of Kentucky College of Law. Thanks for useful comments on the project go to participants in the National Tax Association meeting, the Loyola Los Angeles Law School Tax Colloquium, the Tax Roundtable at the Vienna University of Economics and Business Institute for Austrian and International Tax Law, and the University of Kentucky College of Law Brown Bag Workshop, as well as Professors Albertina Antognini, Richard Ausness, Stefan Bird-Pollan, Zach Bray, Jake Brooks, Miranda Perry Fleischer, Brian Frye, Brian Galle, Michael Healy, Kathy Moore, Katherine Pratt, Ted Seto, and Andrew Woods. -

Intestate Inheritance Rights for Adopted Persons

STATE STATUTES Current Through February 2016 WHAT’S INSIDE Intestate Inheritance Rights Birth parents and for Adopted Persons adopted children Adoptive parents and Leaving a will is the best way to ensure that heirs or adopted children descendants may inherit from your estate. Issues of property distribution may arise when a birth parent Adopted children who are not included in a will or adoptive parent dies without making a valid will or without naming an heir to particular property Summaries of State laws (referred to as intestacy). In these cases, State law determines who may inherit from whom. Laws in all 50 States, the District of Columbia, American Samoa, To find statute Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, information for a and the Virgin Islands specify an adopted person’s particular State, right to inherit from the estate of either adoptive or go to birth parents. https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ laws-policies/state/. Children’s Bureau/ACYF/ACF/HHS 800.394.3366 | Email: [email protected] | https://www.childwelfare.gov Intestate Inheritance Rights for Adopted Persons https://www.childwelfare.gov Birth Parents and Adopted Children Adoptive Parents and Adopted Generally, the court decree that finalizes the adoption Children ends the legal relationship between the birth parent Upon the entry of the final adoption decree, the adopted (also referred to as the biological or natural parent in child is treated by law as if he or she had been born to the the statutes) and the adopted child. There are, however, adopting parents. The adopted child, therefore, gains the exceptions to this policy in some States. -

Comparative Analysis of Legal Regimes with Respect to Fostering Healthy Water Markets

Comparative Analysis of Legal Regimes with Respect to Fostering Healthy Water Markets November 2016 Part III Final Report on Political Economy of Water Markets ! ! ! Comparative!Analysis!of!Legal!Regimes!with!Respect!to!Fostering! Healthy!Water!Markets! ! Part!III! Final!Report!on!Political!Economy!of!Water!Markets! ! November!2016! ! Davíd!Pilz! Megan!Dyson! Bruce!Aylward! Carl!J!Bauer! Amy!Hardberger! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Portland,!Oregon! Preface This paper is one output of a project entitled “The Political Economy of Water Markets.” The project was carried out by Ecosystem Economics LLC and AMP Insights. The outputs of the project include a final report and a set of case studies. The final report consists of three papers and an annex: 1. Healthy Water Markets: A Conceptual Framework by Bruce Aylward, Davíd Pilz, Megan Dyson and Carl J. Bauer 2. Political Economy of Water Markets in the Western United States by Bruce Aylward, Davíd Pilz and Leslie Sanchez 3. Comparative Analysis of Legal Regimes with Respect to Fostering Healthy Water Markets by Davíd Pilz, Megan Dyson, Bruce Aylward, Carl J. Bauer and Amy Hardberger Annex: Water, Public Goods and Market Failure by Bruce Aylward The eight case studies consist of the following. 1. The Evolving Water Market in Chile’s Maipo River Basin by Carl J. Bauer 2. Addressing Overallocation and Water Trade in New South Wales, Australia: Namoi Basin Groundwater by Megan Dyson 3. Evolution of Australian Water Law and the National Water Initiative Framework by Megan Dyson 4. Opportunities for Surface Water Right Marketing in Idaho’s Rapidly Urbanizing Treasure Valley by Jeff Fereday 5. -

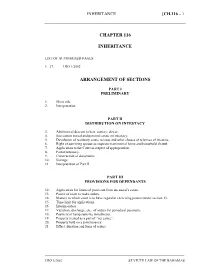

Inheritance Act, 2002

INHERITANCE [CH.116 – 1 INHERITANCE CHAPTER 116 INHERITANCE LIST OF AUTHORISED PAGES 1 –27 LRO 1/2002 ARRANGEMENT OF SECTIONS PART I PRELIMINARY 1. Short title. 2. Interpretation. PART II DISTRIBUTION ON INTESTACY 3. Abolition of descent to heir, curtesy, dower. 4. Succession to real and personal estate on intestacy. 5. Devolution of residuary estate to issue and other classes of relatives of intestate. 6. Right of surviving spouse as respects matrimonial home and household chattel. 7. Application to the Court in respect of appropriation. 8. Partial intestacy. 9. Construction of documents. 10. Savings. 11. Interpretation of Part II. PART III PROVISIONS FOR DEPENDANTS 12. Application for financial provision from deceased’s estate. 13. Power of court to make orders. 14. Matters to which court is to have regard in exercising powers under section 13. 15. Time limit for applications. 16. Interim orders. 17. Variation, discharge, etc., of orders for periodical payments. 18. Payment of lump sums by instalments. 19. Property treated as a part of “net estate”. 20. Property held on a joint tenancy. 21. Effect, duration and form of orders. ––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– LRO 1/2002 STATUTE LAW OF THE BAHAMAS CH.116 – 2] INHERITANCE 22. Provisions as to personal representatives. 23. Interpretation of Part III. PART IV SUPPLEMENTAL 24. Protection against eviction from matrimonial home of spouse. 25. Protection against eviction from matrimonial home of child. 26. Rules. 27. Application of Act. 28. Rule of survivorship. 29. Repeals. FIRST SCHEDULE — Rights of Surviving Spouse as respects the Matrimonial Home. SECOND SCHEDULE — Repeals. STATUTE LAW OF THE BAHAMAS LRO 1/2002 INHERITANCE [CH.116 – 3 CHAPTER 116 INHERITANCE An Act providing for succession to the property of 3 of 2002 deceased persons, and in particular the testamentary disposition and distribution on intestacy of such property; to make financial provisions for the dependants of deceased persons; and for connected purposes. -

Restoring the Public Interest in Western Water Law

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Articles Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship 2020 Restoring the Public Interest in Western Water Law Mark Squillace University of Colorado Law School Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles Part of the Law and Society Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, and the Water Law Commons Citation Information Mark Squillace, Restoring the Public Interest in Western Water Law, 2020 Utah L. Rev. 627, available at https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/articles/1286/. Copyright Statement Copyright protected. Use of materials from this collection beyond the exceptions provided for in the Fair Use and Educational Use clauses of the U.S. Copyright Law may violate federal law. Permission to publish or reproduce is required. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Colorado Law Faculty Scholarship at Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of Colorado Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RESTORING THE PUBLIC INTEREST IN WESTERN WATER LAW Mark Squillace* Abstract American Western states and virtually every country and state with positive water resources law are in perfect agreement about the wisdom of treating their water resources as public property. Not surprisingly, this has led most Western states to articulate a goal of managing these resources in the public interest. But the meaning of the term “public interest,” especially in the context of water resources management, is far from clear. This Article strives to bring clarity to that issue. -

Constitutional Protections of Property Interests in Western Water

CONSTITUTIONAL PROTECTIONS OF PROPERTY INTERESTS IN WESTERN WATER By: James L. Huffman1 & Hertha L. Lund2 "What is common to many is taken least care of, for all men have greater regard for what is their own than for what they possess in common with others." Aristotle I. HISTORICAL FOUNDATIONS OF WESTERN WATER RIGHTS Water scarcity in the western states led to the development of the prior- appropriation water law doctrine.3 The Americans moving into these arid lands created a new system of water law to replace the English common law system doctrine of riparian rights used in the eastern states.4 The riparian system, which had been imported to the eastern states from England, was not suitable to the arid West because it restricted water use to land adjacent to streams.5 In the West, where water was scarce and often located at some distance from where it was needed, the miners and agricultural water users required a system that would allow water to be diverted and used on non-riparian lands. The prior appropriation doctrine followed naturally from the miners' customs for claiming mineral lands. 1 James L. Huffman, Erskine Wood Sr. Professor of Law, Dean of Lewis and Clark Law School. 2 Hertha L. Lund is a practicing attorney at the Lund Law Firm in Bozeman, Montana where she represents landowners in water rights and other litigation. She is a former law clerk of Senior Judge Loren A. Smith of the United States Court of Federal Claims and was a fellow at PERC. The authors thank the Roe Fund at PERC for research support. -

M. Turner Modernizing Slavery

M. Turner Modernizing slavery : investigating the legal dimension Reviews the laws devised by the imperial government to dismantle the slave labor system in the period 1823-38 in order to locate the moment of articulation between chattel and wage slavery. According to the author, the distinguishing feature of these new laws was that the workers lost the right to labor bargaining. Abolition brought free status and civil rights, but the new labor system was not less rigorous. In: New West Indian Guide/ Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 73 (1999), no: 3/4, Leiden, 5-26 This PDF-file was downloaded from http://www.kitlv-journals.nl Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 11:43:20AM via free access MARY TURNER MODERNIZING SLAVERY: INVESTIGATING THE LEGAL DIMENSION The transition from chattel to wage slavery was effected in the British Caribbean by restructuring colonial labor laws.1 The process began in 1823; under pressure from abolitionists inside and outside parliament and with support from the West India lobby, the imperial government made an unprecedented attempt to alter existing owner and slave laws and prepare the slaves for freedom. It marked the seriousness of its intention by prom- ising slave owners £20 million compensation for their property losses when abolition finally took place. Dismantling the slave laws, in the event, took fifteen years: between 1823 and 1833 laws were framed to prepare the slaves for the "civil rights and privileges" of other classes of His Majesty's subjects2 and from 1833 to 1838 when the slave status was abolished and a master-apprentice system was substituted as a preliminary to wage work. -

Behavioral Responses to Inheritance and Gift Taxation: Evidence from Germany

Behavioral Responses to Inheritance and Gift Taxation: Evidence from Germany Ulrich Glogowsky∗ University of Munich [email protected] September 7, 2020 (First version: August 2015) Abstract The desirability of inheritance and gift taxes depends on individuals’ tax responsiveness. This paper demonstrates how strongly, and in what way, the German inheritance and gift tax influences taxpayer behavior. To that end, it combines administrative data with cross-bracket tax variation: a convex kink in the tax liability precedes a concave kink. Extending the bunching approach to such double-kinked tax schedules, I document that individuals tailor their taxable wealth transfers to the schedules. One type of response dominates for inheritances: testators engage in testament planning. The magnitude of the testament-planning response is comparable to that of inter vivos gifts. However, neither the overall responses of gifts nor those of inheritances heavily interfere with tax revenue collection: the associated short-run net-of-tax elasticities of taxable wealth transfers lie below 0.1. JEL codes: H2, H20, H21, H24, H26, H31 Keywords: Wealth-Transfer Tax, Inheritance Tax, Gift Tax, Estate Tax, Real Responses, Tax Avoidance, Tax Evasion, Behavioral Responses, Bunching at Kinks ∗Acknowledgments: I am very grateful to the Co-Editor, Alexander Gelber, and three refer- ees for exremely helpful comments and suggestions. Moreover, I have benefited from comments by and discussions with Alan Auerbach, David Agrawal, Felix Bierbrauer, Spencer Bastani, Thiess Buettner, Richard Burkhauser, Mikael Elinder, Sebastian Findeisen, Scott Findley, Rachel Griffith, Emanuel Hansen, Andreas Haufler, Bas Jacobs, Henrik Kleven, Tuomas Kosonen, Dominika Langen- mayr, Tuomas Matikka, Joerg Paetzold, Andreas Peichl, Rick van der Ploeg, Simeon Schaechtele, Dominik Sachs, Emmanuel Saez, Sebastian Siegloch, Johannes Rincke, Matthias Wrede, Floris Zout- man, and numerous seminar participants.