"Useful Delusions": Tracing the Flying Africans in Ta-Nehisi Coates’S the Water Dancer and Colson Whitehead’S the Underground Railroad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Oprah's Book Club Books

Complete List of Oprah’s Book Club Books 2020 American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family by Robert Kolker Deacon King Kong by James McBride 2019 The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates Waterford does not own, can request Olive, Again by Elizabeth Strout from another library 2018 An American Marriage by Tayari Jones The Sun Does Shine by Anthony Ray Hinton Becoming by Michelle Obama 2017 Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue 2016 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead Love Warrior: A Memoir by Glennon Doyle Martin 2015 Ruby by Cynthia Bond 2014 The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd (announced in 2013, published in 2014) 2012 – “Oprah’s Book Club 2.0,” post-Oprah Winfrey Show club launched Wild: From Lost to Found on the Pacific Crest Trail by Cheryl Strayed The Twelve Tribes of Hattie by Ayana Mathis 2010 Freedom by Jonathan Franzen A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations by Charles Dickens 2009 Say You're One of Them by Uwem Akpan 2008 A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life’s Purpose by Eckhart Tolle The Story of Edgar Sawtelle by David Wroblewski 2007 The Measure of a Man by Sidney Poitier The Road by Cormac McCarthy Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez The Pillars of the Earth by Ken Follett 2006 Night by Elie Wiesel 2005 A Million Little Pieces by James Frey As I Lay Dying, The Sound and the Fury, and Light in August by William Faulkner 2004 One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy The Good Earth by Pearl S. -

Oprah Winfrey's Book Club Selections

BOOK NERD ALERT: OPRAH WINFREY’S BOOK CLUB SELECTIONS Books by Marilynn Robinson o Gilead o Home o Jack o Lila “Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents” by Isabel Wilkerson “Deacon King Kong” by James McBride “Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family” by Robert Kolker “American Dirt” by Jeanine Cummins “Olive, Again” by Elizabeth Strout “The Water Dancer” by Ta-Nehisi Coates “Becoming” by Michelle Obama “The Sun Does Shine” by Anthony Ray Hinton “An American Marriage” by Tayari Jones Behold the Dreamers” by Imbolo Mbue “Love Warrier” by Glennon Doyle Melton “The Underground Railroad” by Colson Whitehead “Ruby” by Cynthia Bond “The Invention of Wings” by Sue Monk Kidd “The Twelve Tribes of Hattie” by Ayana Mathis “Wild” by Cheryl Strayed “A Tale of Two Cities” by Charles Dickens “Great Expectations” by Charlies Dickens “Freedom” by Jonathan Franzen “Say You’re One of Them” by Uwem Akpan “The Story of Edgar Sawtelle” by David Wroblewski “A New Earth” by Eckhart Tolle “The Pillars of the Earth” by Kenn Follett “Love in the Time of Cholera” by Gabriel Garcia Marquez “Middlesex” by Jeffery Eugenides “The Road” by Cormac McCarthy “The Measure of a Man” by Sidney Poitier “Night” by Elie Wiesel “A Million Little Pieces” by James Frey “Light in August” by William Faulkner www.booknerdalert.com Last updated: 10/27/2020 “The Sound and the Fury” by William Faulkner “As I Lay Dying” by William Faulkner “The Good Earth” by Pearl S. Buck “Anna Karenina” by Leo Tolstoy “The Heart is a Lonely Hunter” -

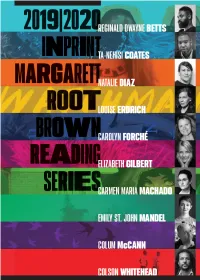

2019-2020-IBRS-Brochure.Pdf

DEAR FRIENDS Welcome to the 2019/2020 Inprint Margarett Root Brown Reading Series—our 39th season. At Inprint, we are proud of the role this series plays in the Houston community, each year presenting an inclusive roster of powerful, bold, award-winning authors whose work inspires and provokes conversation and reflection. Occupying that niche in the local landscape makes us happy—and ensuring that the series is accessible to all is a vital aspect of what we do. We are delighted to share the literary riches of this season—and the ensuing engagement with this work and these ideas—and are grateful to Houston for embracing it. Thank you, as always, for making all of this possible. See you at the readings. Cheers, RICH LEVY Executive Director Monday, September 16, 2019 COLSON WHITEHEAD CULLEN PERFORMANCE HALL, UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON 2019|2020 Tuesday, October 29, 2019 TA-NEHISI COATES CULLEN PERFORMANCE HALL, UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON Monday, November 11, 2019 INPRINT ELIZABETH GILBERT STUDE CONCERT HALL, RICE UNIVERSITY Monday, January 27, 2020 MARGARETT CAROLYN FORCHÉ & CARMEN MARIA MACHADO HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE ROOT Monday, March 9, 2020 LOUISE ERDRICH HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE Monday, March 23, 2020 BROWN REGINALD DWAYNE BETTS & NATALIE DIAZ HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE READING Monday, April 27, 2020 EMILY ST. JOHN MANDEL All readings take place at 7:30 pm & Doors open at 6:45 pm COLUM McCANN SERIES HUBBARD STAGE, ALLEY THEATRE TICKETS All readings begin at 7:30 pm, doors open at 6:45 pm. Each evening will include a reading by featured author(s) and an on-stage interview. -

Nineteenth Century US

—The House Girl by Tara Conklin Pre-Civil War —Mrs. Poe by Lynn Cullen North America —West by Carys Davies —The Daring Ladies of Lowell by Kate Alcott —Washington Black by Esi Edugyan —Mad Boy by Nick Arvin 19th Century —A Stranger Here Below by Charles Fergus —Conjure Women by Afia Atakora (Gideon Stoltz Series #1) —Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood —The Eulogist by Terry Gamble North America —The Autobiography of Mrs. Tom Thumb by —The Signature of all Things by Elizabeth Melanie Benjamin Gilbert —Sons of Blackbird Mountain by Joanne —Where the Lost Wander by Amy Harmon Bischof —A Friend of Mr. Lincoln by Stephen Harrigan —The Movement of Stars by Amy Brill —The Known World by Edward P. Jones —The Last Runaway by Tracy Chevalier —The Invention of Wings by Sue Monk Kidd —Mrs. Grant and Madame Jule by Jennifer —The Rebellion of Miss Lucy Ann Lobdell by Chiaverini William Klaber —The Rathbones by Janice Clark —Song Yet Sung by James McBride —Finn by Jon Clinch —The Good Lord Bird by James McBride —The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates —The Mapmaker’s Children by Sarah McCoy Civil War Era —A Murder in Time by Julie McElwain (Kendra —Cloudsplitter by Russell Banks Donovan Series #1) —Daughter of a Daughter of a Queen by Sarah —The Poe Shadow by Matthew Pearl Bird Explore one of the defining centuries —The All-True Travels and Adventures of Lidie —March by Geraldine Brooks Newton by Jane Smiley of American history. the era of the —Fallen Land by Taylor Brown Civil War, The industrial Revolution, —Chang and Eng by Darin Strauss —White Doves at Morning by James Lee Burke Emancipation, and Reconstruction. -

The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates — Freed Spirits | Financial

The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates — freed spirits | Financial... https://www.ft.com/content/36a33c1c-cd6a-11e9-b018-ca4456540ea6 Fiction The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates — freed spirits The National Book Award winner’s first foray into fiction melds the fantastical with the brutality of human bondage © Eva Bee Diana Evans SEPTEMBER 27 2019 The classic drama of two brothers with contrasting fates is at the centre of National Book Award winner Ta-Nehisi Coates’s much anticipated first foray into fiction. Ten years in the making, amid acclaimed journalism and long-form essayistic writing filling three books, most notably Between the World and Me, The Water Dancer is a vast and hugely ambitious undertaking, not just for its subject matter — the horrific innards of American slavery — but its shift in authorial form. The essential preoccupations remain the same, though: the theft and health of black bodies in the face of white supremacy on US soil. Hiram Walker, upstanding, hardworking, gifted and a slave, is brother to Maynard Walker, lazy, drunken, failed yet white, their father the once powerful leader of a Virginia plantation called Lockless. The tobacco fields are fading. Slaves, or, in the novel’s chosen language, “the Tasked”, are being sold off down “Natchez-way”, a hell along the Mississippi where “the Task” plays out in its most extreme and merciless form. Hiram’s mother Rose was also sold, when Hiram was a child, and the memory of this becomes a kind of key to what emerges as an otherworldly talent, a superpower, in fact, that enables Hiram to magically transfer the Tasked to freedom. -

A Novel. by Ta-Nehisi Coates One World, 2019, 416 Pages ISBN: 978-0-399-59059-7

International Review of Literary Studies ISSN Print: 2709-7013, Online: 2709-7021 Vol. 3, Issue 1 March 2021 Book Review The Water Dancer (Oprah's Book Club): A Novel. By Ta-Nehisi Coates One World, 2019, 416 pages ISBN: 978-0-399-59059-7 Azra Khanam1; Noreen Zameer2 International Review of Literary Studies Vol. 3, No. 1; March 2021, pp. 55-59 Published by: MARS Research Forum The Water Dancer is a debut novel by the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, Ta-Nehisi Coates. This novel is a story of dreadful treatment of human beings under slavery, portraying the life of slaves on a tobacco plantation in Virginia, bringing for the separation of children and their parents, separation of husbands and wives, of the pains and sufferings of the people in the Underground Pathways to carry the people to freedom, in the south in the mid-1800's. The writer brings fore the story of to the demise of Southern tobacco plantations, resulting in the sale of enslaved. The writer brings fore not only the interactions between the “Quality -the plantation owners” and the “Tasked the enslaved” on tobacco plantation, but also the mindsets of the Low Whites, who transmit their deprivation to the enslaved blacks, inspired by having a feel of power and dominance. The deep personal thoughts make this book very influential as a black reader can relate to the characters on a realistic level. The story goes deeper into the politics and the freedom of slaves. The Water Dancer brings for the life-story of Hiram Walker, the black son of a black mother and a white plantation owner, a young man who efforts to free confined people from servitude in the American South. -

NMAAHC Summer Reading Challenge!

N M A A H C S U M M E R R E A D I N G C H A L L E N G E "READING THROUGH THE GALLERIES" SUMMER 2020 GRADES 3 TO 12 AND EDUCATORS Join the NMAAHC in summer 2020 for a new digital experience, “Reading Through the Galleries,” the NMAAHC Summer Reading Challenge! Created for 3rd - 12th grade students and educators, the book selections are curated to provide enjoyment and enrichment about African American history and culture. The “Reading Through the Galleries” runs from June through August. Galleries June: History N M A A H C THEME AND ACTIVITIES S U M M E R R E A D I N G C H A L L E N G E For 2020, the book selection is "READING THROUGH THE GALLERIES" based on the galleries at NMAAHC. Read your way through The National Museum of African the permanent galleries and the American History and Culture temporary exhibition. debuts for 2020 for a new digital experience, the NMAAHC Each month between June and Summer Reading Club. This is a August, NMAAHC educators will self-guided program for 3rd - 12th provide a book list based on one grade students and their of the permanent galleries: educators to read suggested History (June), Community (July), selections by NMAAHC educators. and Culture (August). The lists will feature books suitable for various grades as well as educators. The literature selections consist of fiction and non-fiction, and are DIVISIONS chosen for enjoyment and enrichment about African Sojourners (Grades 3 - 5) American history." Navigators (Grades 6 - 8) Innovators (Grades 9 - 12) Educators (Grades 3 - 12) READING LIST SUBMISSIONS TABLE OF CONENTS Each month, you can submit your How to Participate: 2 - 3 reading list and earn a certificate. -

Antiracism And African American Experience *Acd

ANTIRACISM AND AFRICAN AMERICAN EXPERIENCE *ACD also available B = Biography G = Graphic Novel KIDS JP (picture book) FIC The Big Umbrella Amy June Bates (2018) Lil’ Dan, the Drummer Boy: A Civil War Story by Romare Bearden (2003) Whoever You Are by Mem Fox (1997) When Gorilla Goes Walking by Nikki Grimes (2007) Her Stories: African American Folktales, Fairy Tales, and True Tales by Virginia Hamilton (1995) I Just Want to Say Good Night by Rachel Isadora (2017) Quit Calling Me a Monster! by Jory John and Bob Shea (2016) Hi Cat! by Ezra Jack Keats (1999) Pet Show by Ezra Jack Keats (2001) Peter’s Chair by Ezra Jack Keats (1998) The Snowy Day by Ezra Jack Keats (1962) John Henry by Julius Lester (1994) Henry’s Freedom Box by Ellen Levine (2007) Daisy and the Doll by Michael Madearis (2000) Rhyme Time Valentine by Nancy Poydar (2003) D Is For Drinking Gourd: An African American Alphabet by Nancy I. Sanders (2007) Tops and Bottoms by Janet Stephens (1995) The Day You Begin by Jacqueline Woodson (2018) JP (picture book) NONFICTION The Undefeated by Kwame Alexander (2018) Whoosh!: Lonnie Johnson’s Super Soaking Stream of Inventions by Chris Barton (2016) B She Persisted by Chelsea Clinton (2017) Planting Stories: The Life of Librarian and Storyteller Pura Belpre by Anika Adama Denise (2019) B George Washington Carver by Vicky Franchino (2002) B Superheroes are Everywhere by Kamala Harris (2019) B Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness by Anastasia Higginbotham (2018) The Oldest Student: How Mary Walker Learned to Read by Rita L. -

Beloved and the Water Dancer: a Longitudinal Study of Book Reviews from 1987 and 2019

Portland State University PDXScholar Book Publishing Final Research Paper English 5-2020 Beloved and the Water Dancer: A Longitudinal Study of Book Reviews From 1987 and 2019 Tiffany Watson Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper Part of the Mass Communication Commons, and the Publishing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Watson, Tiffany, "Beloved and the Water Dancer: A Longitudinal Study of Book Reviews From 1987 and 2019" (2020). Book Publishing Final Research Paper. 53. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/eng_bookpubpaper/53 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Book Publishing Final Research Paper by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Beloved and Th e Water Dancer A longitudinal study of book reviews from 1987 and 2019 by Tiff any Watson Introduction: There is a trail of profoundly pessimistic opinions on the state of book re- views and critics from Lorentzen¹ to Hardwick2to Marshall and McCar- thy3to Poe4to Pope⁵. ¹ “Like this or Die” 2 “The Decline of Book Reviewing” In earlier drafts, I tapped into that same despair. I considered calling this 3 “Our Critics, Right or Wrong?” essay “The Death of the Book Reviewer”. I must admit I was committed to 4 Marginalia ⁵ “An Essay on Criticism” the allusion more than to the truth of such a statement. Because, as I read each essay which laid out the faults of the then most-recent form of book reviewing, I came to the conclusion that if the book reviewer is to die, it is a very slow death and much more like obsolescence. -

Oprah's Book Club 2.0 Is a Book the Twelve Tribes of Hattie Their Small Hometown and Confronts the Club Founded June 1, 2012 Forces That Traumatized Her Early Years

2017 A man who spent thirty years on death row for a crime he did not commit Oprah’s Book Behold the Dreamers describes how he became a victim of a by Imbolo Mbue flawed legal system, recounting the years he shared with fellow inmates Club 2.0 Call it a recession novel, or an who were eventually executed before immigrant tale -- both are true. In 2007, his exoneration. Manhattan-based Cameroonian immigrant Jende Jonga gets a job Becoming chauffeuring for Lehman Brothers executive Clark Edwards, easing the by Michelle Obama financial strain on his family. At first, all Michelle Obama invites readers into goes well, but problems in the her world, chronicling the experiences Edwards' marriage lead to problems for that have shaped her—from her the Jongas, and when Lehman falls, childhood on the South Side of both families are caught up in the Chicago to her years as an executive terrible aftermath. balancing the demands of motherhood and work, to her time spent at the 2018 world’s most famous address. With unerring honesty and lively wit, she An American Marriage describes her triumphs and her by Tayari Jones disappointments, both public and private, telling her full story as she has Celestial and Roy are newly married lived it—in her own words and on her professionals leaning in to a bright own terms. future when Roy is convicted of a crime he did not commit. This is not a heroes vs. villains tale with a tidy resolution. It The Water Dancer is a complicated, messy, moving, and by Ta-Nehisi Coates Mount Vernon thought-provoking story about love, family, and the wide-reaching effects of A Virginia slave narrowly escapes a City Library incarceration.