The Color of Love and the Haptic Object of Film History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

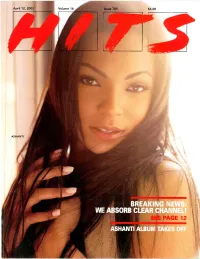

April 12, 2002 Issue

April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue '89 $6.00 ASHANTI IF it COMES FROM the HEART, THENyouKNOW that IT'S TRUE... theCOLORofLOVE "The guys went back to the formula that works...with Babyface producing it and the greatest voices in music behind it ...it's a smash..." Cat Thomas KLUC/Las Vegas "Vintage Boyz II Men, you can't sleep on it...a no brainer sound that always works...Babyface and Boyz II Men a perfect combination..." Byron Kennedy KSFM/Sacramento "Boyz II Men is definitely bringin that `Boyz II Men' flava back...Gonna break through like a monster!" Eman KPWR/Los Angeles PRODUCED by BABYFACE XN SII - fur Sao 1 III\ \\Es.It iti viNA! ARM&SNykx,aristo.coni421111211.1.ta Itccoi ds. loc., a unit of RIG Foicrtainlocni. 1i -r by Q \Mil I April 12, 2002 Volume 16 Issue 789 DENNIS LAVINTHAL Publisher ISLAND HOPPING LENNY BEER Editor In Chief No man is an Island, but this woman is more than up to the task. TONI PROFERA Island President Julie Greenwald has been working with IDJ ruler Executive Editor Lyor Cohen so long, the two have become a tag team. This week, KAREN GLAUBER they've pinned the charts with the #1 debut of Ashanti's self -titled bow, President, HITS Magazine three other IDJ titles in the Top 10 (0 Brother, Ludcaris and Jay-Z/R. TODD HENSLEY President, HITS Online Ventures Kelly), and two more in the Top 20 (Nickelback and Ja Rule). Now all she has to do is live down this HITS Contents appearance. -

By Anne-Sophie Adelys

by Anne-Sophie Adelys © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz 3 © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz My name is Anne-Sophie Adelys. I’m French and have been living in New Zealand since 2001. I’m an artist. A painter. Each week I check “The Big idea” website for any open call for artists. On Saturday the 29th of June 2013, I answered an artist call titled: “Artist for a fringe campaign on Porn” posted by the organisation: The Porn Project. This diary documents the process of my work around this project. I’m not a writer and English is not even my first language. Far from a paper, this diary only serves one purpose: documenting my process while working on ‘The Porn Project’. Note: I have asked my friend Becky to proof-read the diary to make sure my ‘FrenchGlish’ is not too distracting for English readers. But her response was “your FrenchGlish is damn cute”. So I assume she has left it as is… © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz 4 4 © Anne-Sophie Adelys - 2013 - www.adelys.co.nz The artist call as per The Big Idea post (http://www.thebigidea.co.nz) Artists for a fringe campaign on porn 28 June 2013 Organisation/person name: The Porn Project Work type: Casual Work classification: OTHER Job description: The Porn Project A Fringe Art Campaign Tāmaki Makaurau/Auckland, Aotearoa/New Zealand August, 2013 In 2012, Pornography in the Public Eye was launched by people at the University of Auckland to explore issues in relation to pornography through research, art and community-based action. -

Explicit Image Detection Using Ycbcr Space Color Model As Skin Detection

Applications of Mathematics and Computer Engineering Explicit Image Detection using YCbCr Space Color Model as Skin Detection JORGE ALBERTO MARCIAL BASILIO1, GUALBERTO AGUILAR TORRES2, GABRIEL SÁNCHEZ PÉREZ3, L. KARINA TOSCANO MEDINA4, HÉCTOR M. PÉREZ MEANA5 Sección de Estudios de Posgrados e Investigación 1Escuela Superior de Ingeniería Mecánica y Eléctrica Unidad Culhuacan Santa Ana #1000 Col. San Francisco Culhuacan, Del. Coyoacán C.P. 04430 MEXICO CITY [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract: - In this paper a novel way to detect explicit content images is proposed using the YCbCr space color, moreover the color pixels percentage that are within the image is calculated which are susceptible to be a tone skin. The main goal to use this method is to apply to forensic analysis or pornographic images detection on storage devices such as hard disk, USB memories, etc. The results obtained using the proposed method are compared with Paraben’s Porn Detection Stick software which is one of the most commercial devices used for detecting pornographic images. The proposed algorithm achieved identify up to 88.8% of the explicit content images, and 5% of false positives, the Paraben’s Porn Detection Stick software achieved 89.7% of effectiveness for the same set of images but with a 6.8% of false positives. In both cases were used a set of 1000 images, 550 natural images, and 450 with highly explicit content. Finally the proposed algorithm effectiveness shows that the methodology applied to explicit image detection was successfully proved vs Paraben’s Porn Detection Stick software. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

Computational RYB Color Model and Its Applications

IIEEJ Transactions on Image Electronics and Visual Computing Vol.5 No.2 (2017) -- Special Issue on Application-Based Image Processing Technologies -- Computational RYB Color Model and its Applications Junichi SUGITA† (Member), Tokiichiro TAKAHASHI†† (Member) †Tokyo Healthcare University, ††Tokyo Denki University/UEI Research <Summary> The red-yellow-blue (RYB) color model is a subtractive model based on pigment color mixing and is widely used in art education. In the RYB color model, red, yellow, and blue are defined as the primary colors. In this study, we apply this model to computers by formulating a conversion between the red-green-blue (RGB) and RYB color spaces. In addition, we present a class of compositing methods in the RYB color space. Moreover, we prescribe the appropriate uses of these compo- siting methods in different situations. By using RYB color compositing, paint-like compositing can be easily achieved. We also verified the effectiveness of our proposed method by using several experiments and demonstrated its application on the basis of RYB color compositing. Keywords: RYB, RGB, CMY(K), color model, color space, color compositing man perception system and computer displays, most com- 1. Introduction puter applications use the red-green-blue (RGB) color mod- Most people have had the experience of creating an arbi- el3); however, this model is not comprehensible for many trary color by mixing different color pigments on a palette or people who not trained in the RGB color model because of a canvas. The red-yellow-blue (RYB) color model proposed its use of additive color mixing. As shown in Fig. -

Tnemec Colorbook

COLORBOOK WHITES 00WH Tnemec White � 06WH Albatross � 07WH Winter Mist � 08WH Acropolis � LRV 84% LRV 82% LRV 80% LRV 72% 01WH Ash White � 02WH Iceberg � 03WH Daisy � 04WH Silver Pearl � LRV 84% LRV 84% LRV 75% LRV 76% 12WH Milkweed � 13WH French Vanilla � 14WH Veiled � 15WH Aspen � LRV 78% LRV 73% LRV 78% LRV 72% 15BR Pale � 22BR Nova � 57BR Cloud � 79BR Colliseum � LRV 83% LRV 81% LRV 75% LRV 67% NOTE: Colors represented are digital reproductions of actual standards and will vary in appearance due to differences in monitor and video card output. These digital representations should not be used to finalize color selection(s). Please contact your local Tnemec Coatings Consultant for color-accurate samples or for assistance with suitable primer and finish coat selections and color matching. LRV = Light Reflectance Value � Standard color and gloss warranty is available in this color for Fluoronar and HydroFlon products. Other colors may be included. Contact your Tnemec representative for more information. GRAYS 30GR Comet � 24GR Lightpole � 43GR Constellation � 37GR Gradation � LRV 75% LRV 62% LRV 71% LRV 65% 25GR Grey Day � 31GR Slate Gray � 57GR Aluminum � 38GR Dove Gray � LRV 46% LRV 61% LRV 46% LRV 58% 33GR Gray – ANSI No. 61 � 32GR Light Gray – ANSI No. 70 � 46GR Sinker � 39GR Pigeon � LRV 33% LRV 44% LRV 26% LRV 42% 35GR Black � 34GR Deep Space � 48GR Moon Shadow � 41GR Hammerhead � LRV 4% LRV 12% LRV 10% LRV 17% NOTE: Colors represented are digital reproductions of actual standards and will vary in appearance due to differences in monitor and video card output. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

Concert: Choral Collage Derrick Fox

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC All Concert & Recital Programs Concert & Recital Programs 10-10-2015 Concert: Choral Collage Derrick Fox Janet Galván Ithaca College Chorus Ithaca College Madrigal Singers Ithaca College Women's Chorale See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Fox, Derrick; Galván, Janet; Ithaca College Chorus; Ithaca College Madrigal Singers; Ithaca College Women's Chorale; and Ithaca College Choir, "Concert: Choral Collage" (2015). All Concert & Recital Programs. 1240. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1240 This Program is brought to you for free and open access by the Concert & Recital Programs at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Concert & Recital Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. Authors Derrick Fox, Janet Galván, Ithaca College Chorus, Ithaca College Madrigal Singers, Ithaca College Women's Chorale, and Ithaca College Choir This program is available at Digital Commons @ IC: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/music_programs/1240 Choral Collage Ithaca College Chorus Derrick Fox, conductor Ithaca College Madrigal Singers Derrick Fox, conductor Ithaca College Women's Chorale Janet Galván, conductor Ithaca College Choir Janet Galván, conductor Ford Hall Saturday, October 10th, 2015 7:30 pm Program Ithaca College Chorus Derrick Fox, conductor Adam Good, graduate assistant Jon Vogtle and Alexander Greenberg, collaborative pianists This Beautiful Earth "Celebration" Ke Nale Monna Sotho Folk Songs "Remembrance" Requiem a tre voci Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924) Erik Kibelsbeck*, organ David Quiggle*, viola "The Earth" The Ground Ola Gjeilo from Sunrise Mass (b. 1978) Lindsay Gilmour*, choreography "The Heavens" Tonight Eternity Alone Rene Clausen (b. -

Kelvin Color Temperature

KELVIN COLOR TEMPERATURE William Thompson Kelvin was a 19th century physicist and mathematician who invented a temperature scale that had absolute zero as its low endpoint. In physics, absolute zero is a very cold temperature, the coldest possible, at which no heat exists and kinetic energy (movement) ceases. On the Celsius scale absolute zero is -273 degrees, and on the Fahrenheit scale it is -459 degrees. The Kelvin temperature scale is often used for scientific measurements. Kelvins, as the degrees are now called, are derived from the actual temperature of a black body radiator, which means a black material heated to that temperature. An incandescent filament is very dark, and approaches being a black body radiator, so the actual temperature of an incandescent filament is somewhat close to its color temperature in Kelvins. The color temperature of a lamp is very important in the television industry where the camera must be calibrated for white balance. This is often done by focusing the camera on a white card in the available lighting and tweaking it so that the card reads as true white. All other colors will automatically adjust so that they read properly. This is especially important to reproduce “normal” looking skin tones. In theatre applications, where it is only important for colors to read properly to the human eye, the exact color temperature of lamps is not so important. Incandescent lamps tend to have a color temperature around 3200 K, but this is true only if they are operating with full voltage. Remember that dimmers work by varying the voltage pressure supplied to the lamp. -

RGB Color Code According to the Commission for the Geological Map of the World (CGMW), Paris, France

RGB Color Code according to the Commission for the Geological Map of the World (CGMW), Paris, France Holocene 254/242/236 Tithonian 217/241/247 Famennian 242/237/197 Ediacaran 254/217/106 254/242/224 Upper Neo- Upper Upper 255/242/211 Kimmeridgian 204/236/244 241/225/157 Frasnian 242/237/173 proterozoic Cryogenian 254/204/92 179/227/238 99 254/179/66 Pleistocene "Ionian" 255/242/199 Oxfordian 191/231/241 Middle Givetian 241/225/133 Tonian 254/191/78 255/242/174 241/200/104 Calabrian 255/242/186 Callovian 191/231/229 203/140/55 Eifelian 241/213/118 Stenian 254/217/154 Quaternary 249/249/127 Meso- Gelasian 255/237/179 Bathonian 179/226/227 247/53/ proterozoic Ectasian Middle Emsian 229/208/117 253/204/138 Lower 253/180/98 Pliocene Piacenzian 255/255/191 52/178/201 128/207/216 Bajocian 166/221/224 Pragian 229/196/104 Calymmian 253/192/122 229/172/77 255/255/153 Zanclean 255/255/179 Aalenian 154/217/221 Lochkovian 229/183/90 Statherian 248/117/167 Devonian Pridoli Messinian 255/255/115 Toarcian 153/206/227 230/245/225 Paleo- Orosirian 247/104/152 103/197/202 230/245/225 247/67/112 proterozoic Tortonian 255/255/102 128/197/221 Rhyacian 247/91/137 Jurassic Pliensbachian Ludfordian 217/240/223 Lower Ludlow Proterozoic 247/67/112 255/230/25 Miocene Serravallian 255/255/89 66/174/208 Sinemurian 103/188/216 191/230/207 Gorstian 204/236/221 Siderian 247/79/124 242/249/29 255/255/0 Langhian 255/255/77 78/179/211 Hettangian Wenlock Homerian 204/235/209 Neoarchean 250/167/200 255/255/65 Burdigalian Rhaetian 227/185/219 179/225/182 179/225/194 Sheinwoodian -

Securedge™ and Metal Flat Sheet Color Chart

EXPERIENCE THE CARLISLE DIFFERENCE SecurEdge™ and Metal Flat Sheet Color Chart STONE WHITE BONE WHITE REGAL WHITE SANDSTONE ALMOND SIERRA TAN BUCKSKIN MEDIUM BRONZE DARK BRONZE ANTIQUE BRONZE MIDNIGHT BRONZE AGED BRONZE MANSARD BROWN BLACK CITYSCAPE SLATE GRAY GRANITE L MUSKET GRAY CHARCOAL IRON ORE HEMLOCK GREEN PATINA GREEN FOREST GREEN HARTFORD GREEN BURGUNDY COLONIAL RED TERRA COTTA CARDINAL RED TEAL MILITARY BLUE PACIFIC BLUE INTERSTATE BLUE AWARD BLUE SILVER P ZINC P WEATHERED ZINC P CHAMPAGNE P COPPER PENNY P AGED COPPER P DREXLUME™ M P = PREMIUM M = MILL FINISH L = LOW GLOSS COLOR = Standard Product P = CRRC Approved Finishes Cool Roof Product Options SR SRI 24 ga x 20" 24 ga x 48" 22 ga x 48" 26 ga x 20" 26 ga x 27.5" 26 ga x 48" 0.032 x 20" 0.032 x 48" 0.040 X 48" 0.050 x 48" 0.063 x 48" Rated Standard Colors Aged Bronze 0.29 29 P Almond 0.53 62 P Antique Bronze 0.29 28 Black 0.20 17 Bone White 0.67 81 P Buckskin 0.38 41 Burgundy 0.24 23 Charcoal 0.27 27 P Cityscape 0.44 49 P Colonial Red 0.32 34 P Dark Bronze 0.26 24 P Forest Green 0.10 6 Hartford Green 0.29 29 Hemlock Green 0.29 29 P Interstate Blue 0.13 8 Iron Ore 0.27 26 Mansard Brown 0.29 29 P Medium Bronze 0.26 26 P Midnight Bronze 0.06 0 Military Blue 0.29 29 P Musket Gray 0.31 32 P Pacific Blue 0.25 24 P Patina Green 0.33 34 P Regal White 0.60 78 Sandstone 0.49 56 P Sierra Tan 0.36 39 P Slate Gray 0.37 40 P Stone White 0.64 77 P Teal 0.26 25 P Terra Cotta 0.36 39 P Low Gloss Colors Aspen Bronze 0.26 26 P Autumn Red 0.32 34 P Chestnut Brown 0.29 29 P Classic Bronze 0.29 -

Color Temperature and at 5,600 Degrees Kelvin It Will Begin to Appear Blue

4,800 degrees it will glow a greenish color Color Temperature and at 5,600 degrees Kelvin it will begin to appear blue. But light itself has no heat; Color temperature is usually used so for photography it is just a measure- to mean white balance, white point or a ment of the hue of a specific type of light means of describing the color of white source. light. This is a very difficult concept to ex- plain, because–”Isn’t white always white?” The human brain is incred- ibly adept at quickly correcting for changes in the color temperature of light; many different kinds of light all seem “white” to us. When moving from a bright daylight environment to a room lit by a candle all that will appear to change, to the naked eye, is the light level. Yet record these two situations shooting color film, digital photographs or with tape in an unbalanced camcorder and the outside images will have a blueish hue and the inside images will have a heavy orange cast. The brain quickly adjust to the changes, mak- ing what is perceived as white ap- pear white, whereas film, digital im- ages and camcorders are balanced for one particular color and anything that deviates from this will produce a color cast. A GUIDE TO COLOR TEMPERATURE The color of light is measured by the Kelvin scale . This is a sci- entific temperature scale used to measure the exact temperature of objects. If you heat a carbon rod to 3,200 degrees, it glows orange.