Storia Della Notazione Musicale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liste Représentative Du Patrimoine Culturel Immatériel De L'humanité

Liste représentative du patrimoine culturel immatériel de l’humanité Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Al-Ayyala, un art traditionnel du Oman - Émirats spectacle dans le Sultanat d’Oman et 2014 2014 01012 arabes unis aux Émirats arabes unis Al-Zajal, poésie déclamée ou chantée Liban 2014 2014 01000 L’art et le symbolisme traditionnels du kelaghayi, fabrication et port de foulards Azerbaïdjan 2014 2014 00669 en soie pour les femmes L’art traditionnel kazakh du dombra kuï Kazakhstan 2014 2014 00011 L’askiya, l’art de la plaisanterie Ouzbékistan 2014 2014 00011 Le baile chino Chili 2014 2014 00988 Bosnie- La broderie de Zmijanje 2014 2014 00990 Herzégovine Le cante alentejano, chant polyphonique Portugal 2014 2014 01007 de l’Alentejo (sud du Portugal) Le cercle de capoeira Brésil 2014 2014 00892 Le chant traditionnel Arirang dans la République 2014 2014 00914 République populaire démocratique de populaire Date de Date récente proclamation Intitulé officiel Pays d’inscriptio Référence ou première n inscription Corée démocratique de Corée Les chants populaires ví et giặm de Viet Nam 2014 2014 01008 Nghệ Tĩnh Connaissances et savoir-faire traditionnels liés à la fabrication des Kazakhstan - 2014 2014 00998 yourtes kirghizes et kazakhes (habitat Kirghizistan nomade des peuples turciques) La danse rituelle au tambour royal Burundi 2014 2014 00989 Ebru, l’art turc du papier marbré Turquie 2014 2014 00644 La fabrication artisanale traditionnelle d’ustensiles en laiton et en -

Three Millennia of Tonewood Knowledge in Chinese Guqin Tradition: Science, Culture, Value, and Relevance for Western Lutherie

Savart Journal Article 1 Three millennia of tonewood knowledge in Chinese guqin tradition: science, culture, value, and relevance for Western lutherie WENJIE CAI1,2 AND HWAN-CHING TAI3 Abstract—The qin, also called guqin, is the most highly valued musical instrument in the culture of Chinese literati. Chinese people have been making guqin for over three thousand years, accumulating much lutherie knowledge under this uninterrupted tradition. In addition to being rare antiques and symbolic cultural objects, it is also widely believed that the sound of Chinese guqin improves gradually with age, maturing over hundreds of years. As such, the status and value of antique guqin in Chinese culture are comparable to those of antique Italian violins in Western culture. For guqin, the supposed acoustic improvement is generally attributed to the effects of wood aging. Ancient Chinese scholars have long discussed how and why aging improves the tone. When aged tonewood was not available, they resorted to various artificial means to accelerate wood aging, including chemical treatments. The cumulative experience of Chinese guqin makers represent a valuable source of tonewood knowledge, because they give us important clues on how to investigate long-term wood changes using modern research tools. In this review, we translated and annotated tonewood knowledge in ancient Chinese books, comparing them with conventional tonewood knowledge in Europe and recent scientific research. This retrospective analysis hopes to highlight the practical value of Chinese lutherie knowledge for 21st-century instrument makers. I. INTRODUCTION In Western musical tradition, the most valuable musical instruments belong to the violin family, especially antique instruments made in Cremona, Italy. -

University of California Santa Cruz the Vietnamese Đàn

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ THE VIETNAMESE ĐÀN BẦU: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF AN INSTRUMENT IN DIASPORA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in MUSIC by LISA BEEBE June 2017 The dissertation of Lisa Beebe is approved: _________________________________________________ Professor Tanya Merchant, Chair _________________________________________________ Professor Dard Neuman _________________________________________________ Jason Gibbs, PhD _____________________________________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Table of Contents List of Figures .............................................................................................................................................. v Chapter One. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 Geography: Vietnam ............................................................................................................................. 6 Historical and Political Context .................................................................................................... 10 Literature Review .............................................................................................................................. 17 Vietnamese Scholarship .............................................................................................................. 17 English Language Literature on Vietnamese Music -

The Preludes in Chinese Style

The Preludes in Chinese Style: Three Selected Piano Preludes from Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi and Zhang Shuai to Exemplify the Varieties of Chinese Piano Preludes D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jingbei Li, D.M.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2019 D.M.A. Document Committee: Professor Steven M. Glaser, Advisor Dr. Arved Ashby Dr. Edward Bak Copyrighted by Jingbei Li, D.M.A 2019 ABSTRACT The piano was first introduced to China in the early part of the twentieth century. Perhaps as a result of this short history, European-derived styles and techniques influenced Chinese composers in developing their own compositional styles for the piano by combining European compositional forms and techniques with Chinese materials and approaches. In this document, my focus is on Chinese piano preludes and their development. Having performed the complete Debussy Preludes Book II on my final doctoral recital, I became interested in comprehensively exploring the genre for it has been utilized by many Chinese composers. This document will take a close look in the way that three modern Chinese composers have adapted their own compositional styles to the genre. Composers Ding Shan-de, Chen Ming-zhi, and Zhang Shuai, while prominent in their homeland, are relatively unknown outside China. The Three Piano Preludes by Ding Shan-de, The Piano Preludes and Fugues by Chen Ming-zhi and The Three Preludes for Piano by Zhang Shuai are three popular works which exhibit Chinese musical idioms and demonstrate the variety of approaches to the genre of the piano prelude bridging the twentieth century. -

List of the 90 Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage

Albania • Albanian Folk Iso-Polyphony (2005) Algeria • The Ahellil of Gourara (2005) Armenia • The Duduk and its Music (2005) Azerbaijan • Azerbaijani Mugham (2003) List of the 90 Masterpieces Bangladesh • Baul Songs (2005) of the Oral and Belgium • The Carnival of Binche (2003) Intangible Belgium, France Heritage of • Processional Giants and Dragons in Belgium and Humanity France (2005) proclaimed Belize, Guatemala, by UNESCO Honduras, Nicaragua • Language, Dance and Music of the Garifuna (2001) Benin, Nigeria and Tog o • The Oral Heritage of Gelede (2001) Bhutan • The Mask Dance of the Drums from Drametse (2005) Bolivia • The Carnival Oruro (2001) • The Andean Cosmovision of the Kallawaya (2003) Brazil • Oral and Graphic Expressions of the Wajapi (2003) • The Samba de Roda of Recôncavo of Bahia (2005) Bulgaria • The Bistritsa Babi – Archaic Polyphony, Dances and Rituals from the Shoplouk Region (2003) Cambodia • The Royal Ballet of Cambodia (2003) • Sbek Thom, Khmer Shadow Theatre (2005) Central African Republic • The Polyphonic Singing of the Aka Pygmies of Central Africa (2003) China • Kun Qu Opera (2001) • The Guqin and its Music (2003) • The Uyghur Muqam of Xinjiang (2005) Colombia • The Carnival of Barranquilla (2003) • The Cultural Space of Palenque de San Basilio (2005) Costa Rica • Oxherding and Oxcart Traditions in Costa Rica (2005) Côte d’Ivoire • The Gbofe of Afounkaha - the Music of the Transverse Trumps of the Tagbana Community (2001) Cuba • La Tumba Francesa (2003) Czech Republic • Slovácko Verbunk, Recruit Dances (2005) -

Curriculum Vitae Bell Yung Professor of Music University of Pittsburgh (January 2011)

Bell Yung’s CV 1 Curriculum Vitae Bell Yung Professor of Music University of Pittsburgh (January 2011) Home Address 504 N. Neville St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Tel: (412) 681-1643 Office Address Room 206, Music Building University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 Tel: (412) 624-4061; Fax: (412) 624-4186 e-mail: [email protected] Education Ph.D. in Music, Harvard University, 1976 Ph.D. in Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1970 B.Sc. in Engineering Physics, University of California, Berkeley, 1964 Piano performance with Kyriana Siloti, 1967-69 Piano pedagogy at Boston University Summer School at Tanglewood, 1967 Performance studies of various instruments in the Javanese gamelan ensemble, particularly on gender barung (metal xylophone) with Pak Djokowaluya, Yogyakarta, summer 1983. Performance studies of various Chinese instruments; in particular qin (seven-string zither) with Masters Tsar Teh-yun of Hong Kong, from 1978 on, and Yao Bingyan of Shanghai, summer of 1980, 81, 82. Academic Employment University of Pittsburgh Professor of Music, 1994 (On leave 1996-98, and on leave half time 98-02) Associate Professor of Music, 1987 Assistant Professor of Music, 1981 University of Hong Kong Kwan Fong Chair in Chinese Music, University of Hong Kong, 1998.2 – 2002.7. Reader in Music, University of Hong Kong, 1996.8-1998.2 (From February 1998 to 2002, I held joint appointments at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Hong Kong, teaching one term a year at each institution.) University of California at Davis, Visiting Associate -

The Case of Nanguan Music in Postwar Taiwan

Amateur Music Clubs and State Intervention/Wang Ying-fen 95 Amateur Music Clubs and State Intervention: The Case of Nanguan Music in Postwar Taiwan Wang Ying-fen Associate Professor National Taiwan University Graduate Institute of Musicology Abstract: Amateur music clubs had been an integral part of the communal life in traditional Taiwan society. They constituted the main vehicle through which traditional art forms had been transmitted from generation to genera- tion. In post-war Taiwan, however, amateur music clubs experienced serious decline. This was partly due to the Nationalist government’s cultural policy to promote Western and Chinese art forms and downgrade local Taiwanese culture, and partly due to the rapid westernization, modernization, industrial- ization, and urbanization that Taiwan society had undergone. In the 1970s, with the change of the political climate both internationally and domestical- ly, the Nationalist government began to pay attention to local culture and to implement a series of projects to promote traditional arts. Among the art forms promoted, nanguan music stood out as one of the best supported due to its high social status, neutral political position, and academic value as recognized by foreign and domestic scholars. State intervention in nanguan started in 1980 and gradually increased its intensity until it reached its peak level in the second half of the 1990s. It has brought many resources to nan- guan clubs, but it has also contributed to the deterioration of the nanguan community both in its musical quality and its members' integrity as amateur musicians. Based on my personal involvement in nanguan, I aim to document in this paper the state intervention in nanguan in the past two decades and to examine its impact on nanguan. -

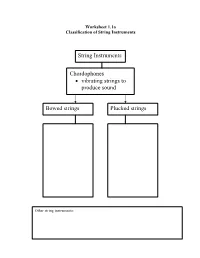

Worksheet 1.1A Classification of String Instruments

Worksheet 1.1a Classification of String Instruments String Instruments Chordophones • vibrating strings to produce sound Bowed strings Plucked strings Other string instruments: Worksheet 1.1b Classification of Wind Instruments Wind Instruments Aerophones • vibrating air columns to produce sound Side-blown End-blown Multiple pipes Double reed Other: Worksheet 1.2a Comparing Jiangnan Sizhu and Xianshi Music (for elementary students) Draw a picture that represents the music (jiangnan sizhu): Draw a picture that represents the music (xianshi): Discuss with your classmates how the two pieces of music are different. Then listen to the two pieces again to identify those differences. Worksheet 1.2b Comparing Jiangnan Sizhu and Xianshi music (for secondary and collegiate-level students) Jiangnan Sizhu (CD track 1) Xianshi (CD track 13) Type of instruments Group size Tempo Melody Texture Rhythm and meter Discuss any similarities and differences. Then listen to the two pieces again to identify the similarities and differences. Proceed to Activity 1.5 (pages 19-20). Worksheet 1.3 Identify Local Music Groups Provide a list of music groups who make music on a regular basis. Classify them as amateur or professional. If you have difficult deciding whether a group is amateur or professional, discuss with classmates or consult with the teacher. You may identify as few as one group and as many as ten in each category. Amateur Professional 1. 1. 2. 2. 3. 3. 4. 4. 5. 5. 6. 6. 7. 7. 8. 8. 9. 9. 10. 10. Based on this list, choose one or two groups for conducting local fieldwork. Ideally, there should be one group from each category for the local fieldwork. -

Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity As Heritage Fund

ElemeNts iNsCriBed iN 2012 oN the UrGeNt saFeguarding List, the represeNtatiVe List iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL HERITAGe aNd the reGister oF Best saFeguarding praCtiCes What is it? UNESCo’s ROLe iNTANGiBLe CULtURAL SECRETARIAT Intangible cultural heritage includes practices, representations, Since its adoption by the 32nd session of the General Conference in HERITAGe FUNd oF THE CoNVeNTION expressions, knowledge and know-how that communities recognize 2003, the Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural The Fund for the Safeguarding of the The List of elements of intangible cultural as part of their cultural heritage. Passed down from generation to Heritage has experienced an extremely rapid ratification, with over Intangible Cultural Heritage can contribute heritage is updated every year by the generation, it is constantly recreated by communities in response to 150 States Parties in the less than 10 years of its existence. In line with financially and technically to State Intangible Cultural Heritage Section. their environment, their interaction with nature and their history, the Convention’s primary objective – to safeguard intangible cultural safeguarding measures. If you would like If you would like to receive more information to participate, please send a contribution. about the 2003 Convention for the providing them with a sense of identity and continuity. heritage – the UNESCO Secretariat has devised a global capacity- Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural building strategy that helps states worldwide, first, to create -

Learning the Malay Traditional Musical Instruments by Using Augmented Reality Application

Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 15 (7): 1622-1625, 2020 ISSN: 1816-949X © Medwell Journals, 2020 Learning the Malay Traditional Musical Instruments by using Augmented Reality Application Masyarah Zulhaida Masmuzidin, Nur Syahela Hussein and Alia Amira Abd Rahman and Mohamad Aqqil Hasman Creative Multimedia Section, Malaysian Institute of Information Technology (MIIT), University Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Abstract: This study proposed the implementation of Augmented Reality (AR) technology to promote the learning experience about Malay traditional musical instruments. The application uses a book as a marker to help the user visualizes the traditional musical instruments, learn the history behind it and how the instruments sounds. As a starting point, a library research has been conducted in order to understand the current state of the art. ADDIE Model has been used and the design and development phases has also been discussed. This AR application is expected to be a tool for promoting the Malay traditional musical instruments for the new young generation. Key words: Augmented reality, Malay musical instruments, digital heritage, music, traditional INTRODUCTION primary and secondary school. The implementation of this syllabus can encourage the young generation to learn Malaysia is a multi-racial country and is well known about their traditional musical instruments. for the richness of its art, culture and heritage. For In terms of promoting the beauty of Malaysia cultures example, Malaysia has a wide range of unique traditional in the eyes of the world, many exhibition has been done by the government agencies. The Department of Malaysia musical instruments that belong to the Malays, Chinese, Museums, for example has 1.500 collections of traditional Indians and from other ethnics. -

Playing Guqin

Playing guqin Carolyn Chen from The Middle Matter: Sound as interstice, ed. Caroline Profanter, Henry Anderson, and Julia Eckhardt (Brussels: umland, 2019), 47-52. The guqin is seven-string Chinese zither. Its body is a single piece of wood, hollowed to resonate, with seven strings strung over the top. Most guqin repertoire is solo. It is a quiet instrument. In folklore, it is played on a mountaintop in the middle of the night, to bring the player into harmony with the self and with nature. The decade-plus that I have studied guqin has been a long meditation on this idea of music as a way to seek for a harmonious relationship with our environment. I first met the guqin by accident. Growing up in New Jersey, I never really encountered opportunities for learning a Chinese instrument. Had I been offered a choice, I might have gravitated toward the conversational-sounding two-string fiddle, the erhu, or the mellow gourd-mounted free-reed pipe, the hulusi. In my last year at university, the music department at Stanford started offering classes in guzheng, the larger, more extroverted and brilliant- sounding relative of the guqin. Then, in my first year of graduate school, I had the fortune of being assigned to assistant-teach for Music of Asia at the University of California, San Diego. One of the first guest lecturers was the neurocomputational ethnomusicologist Alex Khalil, then a graduate student, who had first ventured to China to research stone bells, discovered the guqin, and then returned many times to deepen his study of the instrument. -

Differential Cognitive Responses to Guqin Music and Piano Music in Chinese Subjects: an Event-Related Potential Study

Neurosci Bull February 1, 2008, 24(1): 21-28. http://www.neurosci.cn DOI: 10.1007/s12264-008-0928-2 21 ·Original Article· Differential cognitive responses to guqin music and piano music in Chinese subjects: an event-related potential study Wei-Na ZHU 1, Jun-Jun ZHANG1, Hai-Wei LIU1, Xiao-Jun DING1,2, Yuan-Ye MA1,3, Chang-Le ZHOU1 1Mind, Art and Computation Laboratory, Institute of Artificial Intelligence, School of Information Science and Technology, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China 2College of Foreign Languages and Cultures, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361005, China 3Kunming Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming 650223, China Abstract: Objective To compare the cognitive effects of guqin (the oldest Chinese instrument) music and piano music. Methods Behavioral and event-related potential (ERP) data in a standard two-stimulus auditory oddball task were recorded and analyzed. Results This study replicated the previous results of culture-familiar music effect on Chinese subjects: the greater P300 amplitude in frontal areas in a culture-familiar music environment. At the same time, the difference between guqin music and piano music was observed in N1 and later positive complex (LPC: including P300 and P500): a relatively higher participation of right anterior-temporal areas in Chinese subjects. Conclusion The results suggest that the special features of ERP responses to guqin music are the outcome of Chinese tonal language environments given the similarity between Guqin’s tones and Mandarin lexical tones. Keywords: music; guqin; piano; cognitive process; event-related potential (ERP); N1; LPC; P300 1 Introduction and long-lasting positivity[16]. There are some other studies available regarding about the effects of cross-cultural music Music is considered as a culturally specific phenom- on the musical synchronization[7], music phrase perception enon and characterized with ethnic background, social envi- [15] and music scale structure[16].