Anor of Dagworth with Sorrels

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

Halesworth Area History Notes

Halesworth Area History Notes I. HALESWORTH IN THE 11 th CENTURY Modern Halesworth was founded during the Middle Saxon period (650AD=850AD), and probably situated on the side of a ridge of sand and gravel close to the Town River. The evidence we have of early Halesworth includes a row of large post-holes, a burial of possibly a male of middle age radio-carbon dated to 740AD, and a sub-circular pit containing sheep, pig and ox bones. The ox bones show evidence of butchery. Sherds of ‘Ipswich Ware’ pottery found near the post-holes suggest trading links with the large industrial and mercantile settlement of Ipswich. It is now thought likely that ‘Ipswich Ware’ did not find its way to North Suffolk until after about 720AD. Perhaps Halesworth was also a dependent settlement of the Royal Estate at Blythburgh. By the 11 th century the settlement had moved to the top of the ridge east of the church. It’s possible that ‘Halesuworda’ had become a strategic crossing place where the Town River and its marshy flood plain, were narrow enough to be crossed. Perhaps Halesworth was also a tax centre for the payment of geld, as well as a collecting point for produce from the surrounding countryside with craft goods, agricultural produce and food rents moving up and down the river between Halesworth, Blythburgh and the coastal port of Dunwich. At the time of the Norman Conquest ‘Halesuworda’ consisted of a rural estate held by Aelfric, and two smaller manors whose freemen were under the patronage of Ralph the Constable and Edric of Laxfield. -

London to Ipswich

GREAT EASTERN MAIN LINE LONDON TO IPSWICH © Copyright RailSimulator.com 2012, all rights reserved Release Version 1.0 Train Simulator – GEML London Ipswich 1 ROUTE INFORMATIONINFORMATION................................................................................................................................................................................................................... ........................... 444 1.1 History ....................................................................................................................4 1.1.1 Liverpool Street Station ................................................................................................. 5 1.1.2 Electrification................................................................................................................ 5 1.1.3 Line Features ................................................................................................................ 5 1.2 Rolling Stock .............................................................................................................6 1.3 Franchise History .......................................................................................................6 2 CLASS 360 ‘DESIRO’ ELECTRIC MULTIPLE UNUNITITITIT................................................................................... ..................... 777 2.1 Class 360 .................................................................................................................7 2.2 Design & Specification ................................................................................................7 -

The Long Island Historical Journal

THE LONG ISLAND HISTORICAL JOURNAL United States Army Barracks at Camp Upton, Yaphank, New York c. 1917 Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Nos. 1-2 Starting from fish-shape Paumanok where I was born… Walt Whitman Fall 2003/ Spring 2004 Volume 16, Numbers 1-2 Published by the Department of History and The Center for Regional Policy Studies Stony Brook University Copyright 2004 by the Long Island Historical Journal ISSN 0898-7084 All rights reserved Articles appearing in this journal are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life The editors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Office of the Provost and of the Dean of Social and Behavioral Science, Stony Brook University (SBU). We thank the Center for Excellence and Innovation in Education, SBU, and the Long Island Studies Council for their generous assistance. We appreciate the unstinting cooperation of Ned C. Landsman, Chair, Department of History, SBU, and of past chairpersons Gary J. Marker, Wilbur R. Miller, and Joel T. Rosenthal. The work and support of Ms. Susan Grumet of the SBU History Department has been indispensable. Beginning this year the Center for Regional Policy Studies at SBU became co-publisher of the Long Island Historical Journal. Continued publication would not have been possible without this support. The editors thank Dr. Lee E. Koppelman, Executive Director, and Ms. Edy Jones, Ms. Jennifer Jones, and Ms. Melissa Jones, of the Center’s staff. Special thanks to former editor Marsha Hamilton for the continuous help and guidance she has provided to the new editor. The Long Island Historical Journal is published annually in the spring. -

In England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530

Victoria Shirley The Galfridian Tradition(s) in England, Scotland, and Wales: Texts, Purpose, Context, 1138-1530 A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Literature Cardiff University 2017 i Abstract This thesis examines the responses to and rewritings of the Historia regum Britanniae in England, Scotland, and Wales between 1138 and 1530, and argues that the continued production of the text was directly related to the erasure of its author, Geoffrey of Monmouth. In contrast to earlier studies, which focus on single national or linguistic traditions, this thesis analyses different translations and adaptations of the Historia in a comparative methodology that demonstrates the connections, contrasts and continuities between the various national traditions. Chapter One assesses Geoffrey’s reputation and the critical reception of the Historia between the twelfth and sixteenth centuries, arguing that the text came to be regarded as an authoritative account of British history at the same time as its author’s credibility was challenged. Chapter Two analyses how Geoffrey’s genealogical model of British history came to be rewritten as it was resituated within different narratives of English, Scottish, and Welsh history. Chapter Three demonstrates how the Historia’s description of the island Britain was adapted by later writers to construct geographical landscapes that emphasised the disunity of the island and subverted Geoffrey’s vision of insular unity. Chapter Four identifies how the letters between Britain and Rome in the Historia use argumentative rhetoric, myths of descent, and the discourse of freedom to establish the importance of political, national, or geographical independence. Chapter Five analyses how the relationships between the Arthur and his immediate kin group were used to challenge Geoffrey’s narrative of British history and emphasise problems of legitimacy, inheritance, and succession. -

TO JUNE 2020 (Issue 711) Abbreviations

MIDLAND & GREAT NORTHERN CIRCLE COMBINED INDEX OF BULLETINS AUGUST 1959 (Issue 1) TO JUNE 2020 (Issue 711) Abbreviations: ASLEF Associated Society of Locomotive Engineers M&GSW Midland, Glasgow & South Western Railway and Firemen M&NB Midland and North British Joint Railway ASRS Amalgamated Society of Railway Servants MR Midland Railway BoT Board of Trade Mr M Mr William Marriott B&L Bourn & Lynn Joint Railway MRN Model Railway News BR British Rail[ways] M&GN Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway BTC British Transport Commission N&S Norwich & Spalding Railway B’s Circle Bulletins N&SJt Norfolk & Suffolk Joint Railway CAB Coaching Arrangement Book NCC Norfolk County Council CLC Cheshire Lines Committee NNR North Norfolk Railway [preserved] Cttee Committee NRM National Railway Museum, York E&MR Eastern & Midlands Railway NUR National Union of Railwaymen EDP Eastern Daily Press. O.S. Ordnance Survey GCR Great Central Railway PW&SB Peterborough, Wisbech & Sutton Bridge Rly GER Great Eastern Railway RAF Royal Air Force GNoSR Great North of Scotland Railway Rly Railway GNR Great Northern Railway RCA Railway Clerks’ Association GNWR Glasgow & North Western Railway RCH Railway Clearing House GY&S Great Yarmouth & Stalham Light Railway RDC Rural District Council H&WNR Hunstanton & West Norfolk Railway S&B Spalding & Bourn[e] Railway Jct Junction S&DJR Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway L&FR Lynn & Fakenham Railway SM Station Master L&HR Lynn & Hunstanton Railway SVR Severn Valley Railway L&SB Lynn & Sutton Bridge Railway TMO Traffic Manager’s -

SATURDAY 19Th MARCH 7.30 Pm VILLAGE HALL

Issue No 120 Mar 2005 The annual Tattler Quiz is here again and there are still a few tables left if you would like to join in. Please ring 785588 for tickets - a table of six is £30 - as soon as possible. Each table is encouraged to bring glasses and liquid refreshment though there is food served in the interval. The quiz is on SATURDAY Thank you to Jane Pitcher for this lovely snow photo taken last 19th MARCH week, featuring David labouring 7.30 pm his way up the hill in Tuddenham; VILLAGE HALL what a contrast to the scene on the back cover. Inside this issue…. All tables need to provide wire cutters, plastic comb, wire strippers, slotted 3mm screwdriver & T.A.D.P.O.L.E.spotato peeler in orderPage 2to take part. If you would like to supply a raffleExercise prize Classes that would bePage most 3 appreciated. Money raised will support The Tattler throughQuiz the and next Burns year Night and thePage raffle 3 money will go towards the Village Hall Extension Fund. I look forward to seeing you all promptly for aOrwell 7.30 start Park to Observa- what I hopePage will be a fun evening. As ever, thank you for your supporttory in fi nancing The Tattler4/5/6/7 and its work in Tuddenham. Road and embankment Page 8 works Page 2 March‘05 www.tuddenhamtattler.com Christchurch Mansion are Village Hall Extension hosting a costume collection based on dish cloths until May, Great news - we have been awarded designed by Jayne Lawless, as £5000 from the “Awards for All” lottery well as a gallery of John grant. -

Untitled Typescript}, Macclenny Papers

TABLE OF CONTENTS MAP OF SURVEY AREA SURVEY METHODOLOGY 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT OF SURVEY AREA 5 Physical Characteristics 5 Colonial Period 6 The Federal Period and the Nineteenth Century 24 The Twentieth Century 38 HISTORIC THEMES 46 Residential and Domestic Architecture Agriculture Government, Law and Welfare Education Military Religion Social and Cultural Transportation Commerce Industry, Manufacturing and Crafts THREATS TO HISTORIC RESOURCES 94 RECOMMENDATIONS 95 SOURCES 97 APPENDICES: INDEXES TO SURVEY SITES 101 Numerical Listing Alphabetical Listing SURVEY METHODOLOGY In May 1989 the City of Suffolk contracted with Frazier Associates of Staunton, Virginia to conduct a reconnaissance level architectural survey of 260 historic resources in the southern section of the City. This survey was funded in part by a grant from the National Park Service of the U. S. Department of the Interior through the Virginia Department of Historic Resources. The City of Suffolk is located within the Lower Tidewater Region, one of the geographic areas of the state which the Virginia Department of Historic Resources has created as a part of their State Preservation Plan. / This survey area is approximately 317.42 square miles and corresponds to the southern section of the former Nansemond County. It includes portions of the U. S. G. S. quad maps of Buckhorn, Corapeake, Franklin, Gates, Holland, Riverdale, Suffolk, Whaleyville, and Windsor. Parts of the quads of Lake Drumrnond and Lake Drurnmond N. W. are also in the survey - area butwere not included in tabulations since all of this area is in the Dismal Swamp and contains no historic resources to survey. The detailed boundary of the survey area extends from the City boundary with Isle of Wight County at U. -

Pearce Higgins, Selwyn Archive List

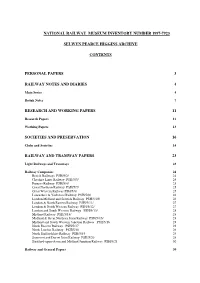

NATIONAL RAILWAY MUSEUM INVENTORY NUMBER 1997-7923 SELWYN PEARCE HIGGINS ARCHIVE CONTENTS PERSONAL PAPERS 3 RAILWAY NOTES AND DIARIES 4 Main Series 4 Rough Notes 7 RESEARCH AND WORKING PAPERS 11 Research Papers 11 Working Papers 13 SOCIETIES AND PRESERVATION 16 Clubs and Societies 16 RAILWAY AND TRAMWAY PAPERS 23 Light Railways and Tramways 23 Railway Companies 24 British Railways PSH/5/2/ 24 Cheshire Lines Railway PSH/5/3/ 24 Furness Railway PSH/5/4/ 25 Great Northern Railway PSH/5/7/ 25 Great Western Railway PSH/5/8/ 25 Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway PSH/5/9/ 26 London Midland and Scottish Railway PSH/5/10/ 26 London & North Eastern Railway PSH/5/11/ 27 London & North Western Railway PSH/5/12/ 27 London and South Western Railway PSH/5/13/ 28 Midland Railway PSH/5/14/ 28 Midland & Great Northern Joint Railway PSH/5/15/ 28 Midland and South Western Junction Railway PSH/5/16 28 North Eastern Railway PSH/5/17 29 North London Railway PSH/5/18 29 North Staffordshire Railway PSH/5/19 29 Somerset and Dorset Joint Railway PSH/5/20 29 Stratford-upon-Avon and Midland Junction Railway PSH/5/21 30 Railway and General Papers 30 EARLY LOCOMOTIVES AND LOCOMOTIVES BUILDING 51 Locomotives 51 Locomotive Builders 52 Individual firms 54 Rolling Stock Builders 67 SIGNALLING AND PERMANENT WAY 68 MISCELLANEOUS NOTEBOOKS AND PAPERS 69 Notebooks 69 Papers, Files and Volumes 85 CORRESPONDENCE 87 PAPERS OF J F BRUTON, J H WALKER AND W H WRIGHT 93 EPHEMERA 96 MAPS AND PLANS 114 POSTCARDS 118 POSTERS AND NOTICES 120 TIMETABLES 123 MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS 134 INDEX 137 Original catalogue prepared by Richard Durack, Curator Archive Collections, National Railway Museum 1996. -

Conservation Area Appraisal

CONSERVATION AREA APPRAISAL Needham Market NW © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2010 INTRODUCTION The conservation area in Needham Market was designated in 1970 by East Suffolk County Council, and inherited by Mid Suffolk District Council at its inception in 1974. It was last appraised and extended by Mid Suffolk District Council in 2000. The Council has a duty to review its conservation area designations from time to time, and this appraisal examines Needham Market under a number of different headings as set out in English Heritage’s ‘Guidance on Conservation Area Appraisals’ (2006). As such it is a straightforward appraisal of Needham Market’s built environment in conservation terms. This document is neither prescriptive nor overly descriptive, but more a demonstration of ‘quality of place’, sufficient for the briefing of the Planning Officer when assessing proposed works in the area. The Town Sign photographs and maps are thus intended to contribute as much as the text itself. As the English Heritage guidelines point out, the appraisal is to be read as a general overview, rather than as a comprehensive listing, and the omission of any particular building, feature or space does not imply that it is of no interest in conservation terms. Text, photographs and map overlays by Patrick Taylor, Conservation Architect, Mid Suffolk District Council 2011. View South-east down High Street Needham Market SE © Crown copyright All rights reserved Mid Suffolk D C Licence no 100017810 2010 TOPOGRAPHICAL FRAMEWORK Needham Market is situated in central Suffolk, eight miles north-west of Ipswich between 20m and 40m above OD. -

Seventeenth Century Settlement of the Nansemond River in Virginia Emmett De Ward Bottoms Old Dominion University

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons History Theses & Dissertations History Spring 1983 Seventeenth Century Settlement of the Nansemond River in Virginia Emmett dE ward Bottoms Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Bottoms, Emmett E.. "Seventeenth Century Settlement of the Nansemond River in Virginia" (1983). Master of Arts (MA), thesis, History, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/9ppr-2744 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/history_etds/24 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEVENTEENTH CENTURY SETTLEMENT OF THE NANSEMOND RIVER IN VIRGINIA by Emmett Edward Bottoms B.S. June 1966, Old Dominion College A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 1983 Approved by: Peter C. Stewart (Director) Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT SEVENTEENTH CENTURY SETTLEMENT OF THE NANSEMOND RIVER IN VIRGINIA Emmett Edward Bottoms Old Dominion University, 1983 Director: Dr. Peter C. Stewart The estuarine Nansemond River in southeastern Virginia provided exploitable resources to Indians and English colonists during the seventeenth century. Coloni zation of the Nansemond, attempted in 1609, was resisted by the Nansemond Indians and was accomplished only after they were decimated and displaced. Anglicans and dissenting Puritans and Quakers established churches and meeting houses along the river. -

The Suffolk Institute of Archaeology

THE SUFFOLKINSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY: ITS LIFE, TIMESANDMEMBERS by STEVENJ. PLUNKETT The one remains —the many change and pass' (Shelley) 1: ROOTS THE SUFFOLKINSTITUTE of Archaeology and History had its birth 150 years ago, in the spring of 1848, under the title of The Bury and West Suffolk Archaeological Institute. It is among the earliest of the County Societies, preceded only by Northamptonshire and Lincolnshire (1844), Norfolk (1846), and the Cambrian, Bedfordshire, Sussex and Buckinghamshire Societies (1847), and contemporary with those of Lancashire and Cheshire. Others, equally successful, followed, and it is a testimony to the social and intellectual timeliness of these foundations that most still flourish and produce Proceedingsdespite a century and a half of changing approaches to the historical and antiquarian materials for the study of which they were created. The immediate impetus to this movement was the formation in December 1843 of the British ArchaeologicalAssociationfor the Encouragementand Preservationof Researchesinto the Arts ancl Monumentsof theEarly and MiddleAges, which in March 1844 produced the first number of the ArchaeologicalJ ournal.The first published members' list, of 1845, shows the members grouped according to the counties in which they lived, indicating the intention that the Association should gather information from, and disseminate discourses into, the counties through a national forum. The thirty-six founding members from Suffolk form an interesting group from a varied social spectrum, including the collector Edward Acton (Grundisburgh), Francis Capper Brooke (Ufford), John Chevallier Cobbold, Sir Thomas Gery Cullum of Hawstead, David Elisha Davy, William Stevenson Fitch, the Ipswich artists Fred Russel and Wat Hagreen, Professor Henslow, Alfred Suckling, Samuel Tyrnms, John Wodderspoon, the Woodbridge geologist William Whincopp, Richard Almack, and the Revd John Mitford (editor of Gentleman'sMagazine).