Can a Judicial Standing Order Disrupt a Norm?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Association of Women Judges

National Association of Women Judges District 1 Quarterly Newsletter New Women Judges Congratulations to the following women judges who were appointed to the bench from 10/15 to 5/17 SUPREME JUDICIAL COURT: Elspeth US BANKRUPTCY COURT: Elizabeth D. Cypher Katz APPEALS COURT: Vickie L. Henry JUVENILE COURT: Susan Oker, Kathryn Phelan Brown, Michela C. Stewart, Kelli Ryan DISTRICT COURT: Jean Curran, Sara DiLisio and Arose Nielsen Weyland Ellis PROBATE AND FAMILY COURT: Mary HOUSING COURT: Maria Theophilis Rudolph Black, Claudine Wyner Retired judges Margot Botsford, Cynthia Cohen and Geraldine Hines are honored by NAWJ past presidents Nan Duffly (SJC ret) and Amy Nechtem (Chief Justice Juvenile Court) and members of District One. (photo credit: C. Anne Fitzgerald) MaryLou Muirhead (Boston Housing Court) and District One hosted a Reception Honoring the Women Judges of Massachusetts at the Brooke Courthouse on June 21, 2017. Many NAWJ members were in attendance as Amy Nechtem (Chief Justice of the Juvenile Court) welcomed and introduced all the women who had been appointed to the bench or elevated to the bench on a higher court since the last Welcome Reception in October 2015. Nan Duffly (SJC ret.) introduced recently retired judges Margot Botsford (SJC), Geraldine Hines (SJC) and Cynthia Cohen (Appeals Court). NAWJ presented them with a small token of gratitude for their collective sixty years of dedicated service on the courts of the Commonwealth. Issue #: [Date] Quick News Dolor Sit Amet - U.S. Magistrate Judge Judith G. Dein has been designated to serve as magistrate judge for the District of Puerto Rico in Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy proceedings recently filed in federal court in San Juan. -

March 18, 2020 Alison J. Nathan, United States District Judge

Revised: March 18, 2020 EMERGENCY INDIVIDUAL RULES AND PRACTICES IN LIGHT OF COVID-19 Alison J. Nathan, United States District Judge Chambers Email: [email protected] Unless otherwise ordered by the Court, these Emergency Individual Rules and Practices apply to all matters before Judge Nathan (whether criminal or civil and whether involving a pro se party or all counseled parties), and they are a supplement to Judge Nathan’s standard Individual Rules and Practices. If there is a conflict between these Rules and Judge Nathan’s standard Individual Rules and Practices, these Rules control. 1. No Paper Submissions Absent Undue Hardship A. No papers, including courtesy hard copies of any filing or document, may be submitted to Chambers. All documents must be filed on ECF or, if permitted or required under the Court’s Individual Rules and Practices, emailed to [email protected]. B. In the event that a party or counsel is unable to submit a document electronically — either by ECF or email — the document may be mailed to the Court. To the maximum extent possible, however, this means of delivery should be avoided, as delivery of mail to the Court is likely to be delayed. 2. Conferences and Proceedings A. In Civil Cases. Unless otherwise ordered by the Court, all conferences and proceedings in civil cases will be held by telephone. In some cases, the Court may direct one of the parties to set up a conference line. In all other cases, the parties should call into the Court’s dedicated conference line at (888) 363-4749, and enter Access Code 919-6964, followed by the pound (#) key. -

Members by Circuit (As of January 3, 2017)

Federal Judges Association - Members by Circuit (as of January 3, 2017) 1st Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Bruce M. Selya Jeffrey R. Howard Kermit Victor Lipez Ojetta Rogeriee Thompson Sandra L. Lynch United States District Court District of Maine D. Brock Hornby George Z. Singal John A. Woodcock, Jr. Jon David LeVy Nancy Torresen United States District Court District of Massachusetts Allison Dale Burroughs Denise Jefferson Casper Douglas P. Woodlock F. Dennis Saylor George A. O'Toole, Jr. Indira Talwani Leo T. Sorokin Mark G. Mastroianni Mark L. Wolf Michael A. Ponsor Patti B. Saris Richard G. Stearns Timothy S. Hillman William G. Young United States District Court District of New Hampshire Joseph A. DiClerico, Jr. Joseph N. LaPlante Landya B. McCafferty Paul J. Barbadoro SteVen J. McAuliffe United States District Court District of Puerto Rico Daniel R. Dominguez Francisco Augusto Besosa Gustavo A. Gelpi, Jr. Jay A. Garcia-Gregory Juan M. Perez-Gimenez Pedro A. Delgado Hernandez United States District Court District of Rhode Island Ernest C. Torres John J. McConnell, Jr. Mary M. Lisi William E. Smith 2nd Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Barrington D. Parker, Jr. Christopher F. Droney Dennis Jacobs Denny Chin Gerard E. Lynch Guido Calabresi John Walker, Jr. Jon O. Newman Jose A. Cabranes Peter W. Hall Pierre N. LeVal Raymond J. Lohier, Jr. Reena Raggi Robert A. Katzmann Robert D. Sack United States District Court District of Connecticut Alan H. NeVas, Sr. Alfred V. Covello Alvin W. Thompson Dominic J. Squatrito Ellen B. -

Attorneys for Epstein Guards Wary of Their Clients Being Singled out For

VOLUME 262—NO. 103 $4.00 WWW. NYLJ.COM TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 26, 2019 Serving the Bench and Bar Since 1888 ©2019 ALM MEDIA PROPERTIES, LLC. COURT OF APPEALS IN BRIEF Chinese Professor’s hearing date of Dec. 3. She also NY Highest Court Judges Spar IP Fraud Case Reassigned mentioned that the payments were coming from a defendant A third judge in the Eastern in the case discussed in the Over How to Define the Word District of New York is now sealed relatedness motion. handling the case of a Chinese While the Curcio question ‘Act’ in Disability Benefits Case citizen accused of stealing an now moves to Chen’s court- American company’s intellec- room, Donnelly issued her tual property on behalf of the order Monday on the related- Office by Patricia Walsh, who was Chinese telecom giant Huawei, ness motion. BY DAN M. CLARK injured when an inmate acciden- according to orders filed Mon- “I have reviewed the Govern- tally fell on her while exiting a day. ment’s letter motion and con- JUDGES on the New York Court of transport van. Walsh broke the CRAIG RUTTLE/AP U.S. District Judge Pamela clude that the cases are not Appeals sparred Monday over how inmate’s fall and ended up with Chen of the Eastern District of presumptively related,” she the word “act,” as in action, should damage to her rotator cuff, cervi- Tova Noel, center, a federal jail guard responsible for monitoring Jeffrey Epstein New York was assigned the case wrote. “Indeed, the Government be defined in relation to an injured cal spine, and back. -

Brief of Amicus Curiae of 28 Domestic

Case: 19-1838 Document: 00117660709 Page: 1 Date Filed: 10/26/2020 Entry ID: 6377027 No. 19-1838 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIRST CIRCUIT __________________________________________________________________ MARIAN RYAN, in her official capacity as Middlesex County District Attorney; RACHAEL ROLLINS, in her official capacity as Suffolk County District Attorney; COMMITTEE FOR PUBLIC COUNSEL SERVICES; CHELSEA COLLABORATIVE, INC., Plaintiffs-Appellees, v. U.S. IMMIGRATION AND CUSTOMS ENFORCEMENT; MATTEW T. ALBENCE, in his official capacity as Acting Deputy Director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement and Senior Official Performing the Duties of the Director; TODD M. LYONS, in his official capacity as Acting Field Office Director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, Enforcement and Removal Operations; U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HOMELAND SECURITY; CHAD WOLF, in his official capacity as Acting Secretary of United States Department of Homeland Security, Defendants-Appellants. ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF MASSACHUSETTS No. 19-cv-11003 The Hon. Indira Talwani BRIEF OF AMICI CURIAE 28 DOMESTIC AND SEXUAL VIOLENCE ADVOCACY ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR PANEL REHEARING OR REHEARING EN BANC (Counsel listed on inside cover) Case: 19-1838 Document: 00117660709 Page: 2 Date Filed: 10/26/2020 Entry ID: 6377027 Joel A. Fleming (Bar No. 1158979) Lauren Godles Milgroom (Bar No. 1183519) Amanda R. Crawford Block & Leviton LLP 260 Franklin St., Suite 1860 Boston, MA 02110 Tel: (617) 398-5600 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Counsel for Amici Curiae Case: 19-1838 Document: 00117660709 Page: 3 Date Filed: 10/26/2020 Entry ID: 6377027 FEDERAL RULE OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE 29 STATEMENTS Pursuant to Fed. -

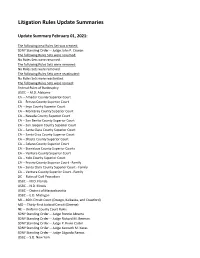

2021-02-01 Litigation Rules Update Summaries

Litigation Rules Update Summaries Update Summary February 01, 2021: The following new Rules Set was created: SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge John P. Cronan The following Rules Sets were renamed: No Rules Sets were renamed. The following Rules Sets were removed: No Rules Sets were removed. The following Rules Sets were reactivated: No Rules Sets were reactivated. The following Rules Sets were revised: Federal Rules of Bankruptcy USDC ‐‐ M.D. Alabama CA ‐‐ Amador County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Fresno County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Inyo County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Monterey County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Nevada County Superior Court CA ‐‐ San Benito County Superior Court CA ‐‐ San Joaquin County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Santa Clara County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Santa Cruz County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Shasta County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Solano County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Stanislaus County Superior Courts CA ‐‐ Ventura County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Yolo County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Fresno County Superior Court ‐ Family CA ‐‐ Santa Clara County Superior Court ‐ Family CA ‐‐ Ventura County Superior Court ‐ Family DC ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure USBC ‐‐ M.D. Florida USBC ‐‐ N.D. Illinois USBC ‐‐ District of Massachusetts USBC ‐‐ E.D. Michigan MI ‐‐ 46th Circuit Court (Otsego, Kalkaska, and Crawford) MO ‐‐ Thirty‐First Judicial Circuit (Greene) NE ‐‐ Uniform County Court Rules SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Ronnie Abrams SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Richard M. Berman SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge P. Kevin Castel SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Kenneth M. Karas SDNY Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Edgardo Ramos USBC ‐‐ S.D. New York NY Appellate Division, Rules of Practice NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, First Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Second Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Third Department NY ‐‐ Appellate Division, Fourth Department USDC ‐‐ District of North Dakota USDC ‐‐ N.D. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Nominations Submitted to The

Administration of Barack Obama, 2014 Nominations Submitted to the Senate November 21, 2014 The following list does not include promotions of members of the Uniformed Services, nominations to the Service Academies, or nominations of Foreign Service Officers. Submitted January 6 Jill A. Pryor, of Georgia, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice Stanley F. Birch, Jr., retired. Carolyn B. McHugh, of Utah, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 10th Circuit, vice Michael R. Murphy, retired. Michelle T. Friedland, of California, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit, vice Raymond C. Fisher, retired. Nancy L. Moritz, of Kansas, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 10th Circuit, vice Deanell Reece Tacha, retired. John B. Owens, of California, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Ninth Circuit, vice Stephen S. Trott, retired. David Jeremiah Barron, of Massachusetts, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the First Circuit, vice Michael Boudin, retired. Robin S. Rosenbaum, of Florida, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice Rosemary Barkett, resigned. Julie E. Carnes, of Georgia, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the 11th Circuit, vice James Larry Edmondson, retired. Gregg Jeffrey Costa, of Texas, to be U.S. Circuit Judge for the Fifth Circuit, vice Fortunato P. Benavides, retired. Rosemary Márquez, of Arizona, to be U.S. District Judge for the District of Arizona, vice Frank R. Zapata, retired. Pamela L. Reeves, of Tennessee, to be U.S. District Judge for the Eastern District of Tennessee, vice Thomas W. Phillips, retiring. -

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Digest of Other White House

Administration of Barack Obama, 2013 Digest of Other White House Announcements December 31, 2013 The following list includes the President's public schedule and other items of general interest announced by the Office of the Press Secretary and not included elsewhere in this Compilation. January 1 In the evening, the President traveled to Honolulu, HI, arriving the following morning. The White House announced that the President will travel to Honolulu, HI, in the evening. January 2 In the morning, upon arrival at Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam, HI, the President traveled to Kailua, HI, where he had separate telephone conversations with Gov. Christopher J. Christie of New Jersey and Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo of New York to discuss Congressional action on the Hurricane Sandy supplemental request. In the afternoon, the President signed H.R. 8, the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. During the day, the President had an intelligence briefing. He also signed H.R. 4310, the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013. January 3 In the morning, the President had a telephone conversation with House Republican Leader Eric Cantor and House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi to extend his welcome to all Members of the 113th Congress. In the afternoon, the President had a telephone conversation with Speaker of the House of Representatives John A. Boehner and House Democratic Leader Nancy Pelosi to congratulate them on being redesignated to lead their respective parties in the House. During the day, the President had an intelligence briefing. The President announced the designation of the following individuals as members of a Presidential delegation to attend the Inauguration of John Dramani Mahama as President of Ghana on January 7: Daniel W. -

2020-12-31 FC-DA Litigation Rules Update Summaries

Litigation Rules Update Summaries Update Summary December 31, 2020: The following new Rules Sets were created: CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge John W. Holcomb CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Pedro V. Castillo CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Stanley Blumenfeld Jr. The following Rules Sets were renamed: No Rules Sets were renamed. The following Rules Sets were removed: No Rules Sets were removed. The following Rules Sets were reactivated: No Rules Sets were reactivated. The following Rules Sets were revised: USBC ‐‐ E.D. Arkansas USBC ‐‐ W.D. Arkansas CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Mark C. Scarsi CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Mag. Jacqueline Chooljian USDC ‐‐ S.D. California USDC ‐‐ N.D. California ‐‐ ADR NDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge William Alsup USBC ‐‐ E.D. California California Rules of Court ‐‐ Appeals California CCP and CRC CA ‐‐ Kings County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Placer County Superior Court CA ‐‐ Family Law CA ‐ California Criminal Procedure California Unlawful Detainer CA ‐‐ Office of Administrative Hearings USDC ‐‐ M.D. Georgia MA ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure ND ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure OH ‐‐ Trumbull County Court of Common Pleas ‐ General SC ‐‐ Magistrate's Court SC ‐‐ Court‐Annexed ADR Rules SD ‐‐ Rules of Civil Procedure USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, Austin Division USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, El Paso and Waco Divisions USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, Midland‐Odessa Divisions USBC ‐‐ W.D. Texas, San Antonio Division WA ‐‐ Chelan County Superior Court WA ‐‐ Clallam County Superior Court WA ‐‐ King County Superior Court WA ‐‐ Skagit County Superior Court WA ‐‐ Yakima County Superior Court Update Summary November 30, 2020: The following new Rules Sets were created: CDCA Standing Order ‐‐ Judge Mark C. -

Updated January 12, 2021

Updated January 12, 2021 1 Executive office of the President (EOP) The Executive Office of the President (EOP) comprises the offices and agencies that support the work of the president at the center of the executive branch of the United States federal government. To provide the President with the support that he or she needs to govern effectively, the Executive Office of the President (EOP) was created in 1939 by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The EOP has responsibility for tasks ranging from communicating the President’s message to the American people to promoting our trade interests abroad. The EOP is also referred to as a 'permanent government', with many policy programs, and the people who implement them, continuing between presidential administrations. This is because there is a need for qualified, knowledgeable civil servants in each office or agency to inform new politicians. With the increase in technological and global advancement, the size of the White House staff has increased to include an array of policy experts to effectively address various fields. There are about 4,000 positions in the EOP, most of which do not require confirmation from the U.S. Senate. Senior staff within the Executive Office of the President have the title Assistant to the President, second-level staff have the title Deputy Assistant to the President, and third-level staff have the title Special Assistant to the President. The core White House staff appointments, and most Executive Office officials generally, are not required to be confirmed by the U.S. Senate, although there are a handful of exceptions (e.g., the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, the Chair and members of the Council of Economic Advisers, and the United States Trade Representative). -

Women of the Mother Court Jadranka Jakovcic

62 • THE FEDERAL LAWYER • August 2018 WOMEN OF THE MOTHER COURT JADRANKA JAKOVCIC he U.S. District Court for the Southern also remembered for having drafted the original complaint in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education.4 She was District of New York (SDNY), colloquially the first African-American woman ever to argue a case before the known as the “Mother Court,” is the U.S. Supreme Court and was successful in nine of the 10 cases she oldest federal court in the United States. argued before it.5 TCreated by President George Washington through Another of the Mother Court’s proud history of judicial firsts was the appointment of Hon. Sonia Sotomayor as its first Hispanic the Judiciary Act of 1789, it was the first court to woman. While serving on the federal bench, she has gained fame as sit under the new U.S. Constitution, preceding the the judge who “saved” Major League Baseball with her strike-ending U.S. Supreme Court by several weeks.1 decision in Silverman v. Major League Baseball Player Relations Committee Inc.,6 which evidenced the qualities of thought and In the words of Hon. Charles Evans Hughes, former chief justice diligence she would later bring to the U.S. Supreme Court. Appoint- of the United States, “the courts are what the judges make them, and ed by President Barack Obama in 2009, Justice Sotomayor is also the district court in New York, from the time of James Duane, Wash- the first Hispanic and the third woman to serve on the U.S. -

Federal Judges Association Current Members by Circuit As of 10/8/2020

Federal Judges Association Current Members by Circuit as of 10/8/2020 1st Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit Jeffrey R. Howard 0 Kermit Victor Lipez (Snr) Sandra L. Lynch Ojetta Rogeriee Thompson United States District Court District of Maine D. Brock Hornby (Snr) 0 Jon David Levy George Z. Singal (Snr) Nancy Torresen John A. Woodcock, Jr. (Snr) United States District Court District of Massachusetts Allison Dale Burroughs 0 Denise Jefferson Casper Timothy S. Hillman Mark G. Mastroianni George A. O'Toole, Jr. (Snr) Michael A. Ponsor (Snr) Patti B. Saris F. Dennis Saylor Leo T. Sorokin Richard G. Stearns Indira Talwani Mark L. Wolf (Snr) Douglas P. Woodlock (Snr) William G. Young United States District Court District of New Hampshire Paul J. Barbadoro 0 Joseph N. Laplante Steven J. McAuliffe (Snr) Landya B. McCafferty Federal Judges Association Current Members by Circuit as of 10/8/2020 United States District Court District of Puerto Rico Francisco Augusto Besosa 0 Pedro A. Delgado Hernandez Daniel R. Dominguez (Snr) Jay A. Garcia-Gregory (Snr) Gustavo A. Gelpi, Jr. Juan M. Perez-Gimenez (Snr) United States District Court District of Rhode Island Mary M. Lisi (Snr) 0 John J. McConnell, Jr. William E. Smith 2nd Circuit United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit Jose A. Cabranes 0 Guido Calabresi (Snr) Denny Chin Christopher F. Droney (Ret) Peter W. Hall Pierre N. Leval (Snr) Raymond J. Lohier, Jr. Gerard E. Lynch (Snr) Jon O. Newman (Snr) Barrington D. Parker, Jr. (Snr) Reena Raggi (Snr) Robert D. Sack (Snr) John M.