La Fanciulla Del West 250

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MODELING HEROINES from GIACAMO PUCCINI's OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MODELING HEROINES FROM GIACAMO PUCCINI’S OPERAS by Shinobu Yoshida A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music: Musicology) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Naomi A. André, Co-Chair Associate Professor Jason Duane Geary, Co-Chair Associate Professor Mark Allan Clague Assistant Professor Victor Román Mendoza © Shinobu Yoshida All rights reserved 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES ...........................................................................................................iii LIST OF APPENDECES................................................................................................... iv I. CHAPTER ONE........................................................................................................... 1 INTRODUCTION: PUCCINI, MUSICOLOGY, AND FEMINIST THEORY II. CHAPTER TWO....................................................................................................... 34 MIMÌ AS THE SENTIMENTAL HEROINE III. CHAPTER THREE ................................................................................................. 70 TURANDOT AS FEMME FATALE IV. CHAPTER FOUR ................................................................................................. 112 MINNIE AS NEW WOMAN V. CHAPTER FIVE..................................................................................................... 157 CONCLUSION APPENDICES………………………………………………………………………….162 BIBLIOGRAPHY.......................................................................................................... -

La Fanciulla Del West Opens Minnesota Opera's 2014-2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 20 AUGUST 2014 CONTACT: JULIE BEHR. 612-342-1612, [email protected] La fanciulla del West opens Minnesota Opera’s 2014-2015 season on September 20 A free, festive outdoor simulcast of opening night’s performance is open to the public in Rice Park Minneapolis – Puccini's La fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West), opera's first "Spaghetti Western," opens Minnesota Opera's 2014-2015 season on September 20, led by Music Director Michael Christie and a powerful trio: Claire Rutter, Rafael Davila, and Greer Grimsley. The drama and excitement of opening night inside Ordway will extend outdoors that evening with a free, live video simulcast under the stars in Rice Park. From the Italian master who wrote La bohème, Madame Butterfly, and Turandot comes a romantic portrait of America’s iconic Golden West. Puccini’s gorgeous melodies and blazing orchestral colors are set against a backdrop of a gold-mining frontier town, where a poker-playing, pistol-wielding saloon owner finds herself in a love triangle with a handsome outlaw and the sheriff who is in hot pursuit of him. Considered by Puccini as one of his greatest works, La fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West) had its successful and highly publicized premiere at the Metropolitan Opera in 1910. Soprano Claire Rutter, who was hailed as “blest with a powerful stage presence and a top-end coloratura like warm steel” by Classical Source, makes her Minnesota Opera debut as the high- spirited Minnie. Tenor Rafael Davila also debuts with the company as the bandit Dick Johnson, who was applauded by Bachtrack as "a real revelation .. -

Puccini's La Fanciulla Del West (The MET: Live in HD)

3/3/2020 Opera: Puccini's La Fanciulla del West (The MET: Live in HD) « All Events This event has passed. Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West (The MET: Live in HD) 18 May, 2019 @ 5:00 pm “The MET: Live in HD” series presents high-definition screenings of opera performances at the Metropolitan Opera House, New York transmitted to cinemas across the world. Now, the Foundation of Arts and Music in Asia (FAMA) brings the opportunity to watch the MET productions in Hong Kong. Soprano Eva-Maria Westbroek sings Puccini’s gun-slinging heroine in this romantic epic of the Wild West. Tenor Jonas Kaufmann makes a heralded return in the role of the outlaw she loves. Baritone Željko Lučić is the vigilante sheri Jack Rance, and Marco Armiliato conducts. Tickets available from hkticketing.com + GOOGLE CALENDAR + ICAL EXPORT https://expatliving.hk/event/puccinis-la-fanciulla-del-west-opera-performance-the-met-live-in-hd/ 1/3 3/3/2020 Opera: Puccini's La Fanciulla del West (The MET: Live in HD) Details Organizer Pricing Date: Foundation for the Arts and Adults $210, Students/ Senior 18 May, 2019 Music in Asia Citizens $180 Time: Phone: 5:00 pm 2579 5533 Event Category: Email: Whats On Calendar [email protected] Event Tags: Website: classical music, Cultural, www.themetinhongkong.info Culture, Film, Living In Hong Kong, opera, Things to do in Hong Kong Website: https://premier.hkticketing.co m/Shows/Show.aspx? sh=LAFAN0519 Venue bethanie theatre 139 Pok Fu Lam Road, Pok Fu Lam Hong Kong + Google Map Phone: 25848918 Website: https://www.hkapa.edu « Jason Mraz Good Vibes Tour Hong Kong 2019 Fascinating Strings – An Evening with HKCO Huqin Principals » https://expatliving.hk/event/puccinis-la-fanciulla-del-west-opera-performance-the-met-live-in-hd/ 2/3 3/3/2020 Muhly's Marnie (The MET: Live in HD 2019 season in cinemas) « All Events This event has passed. -

Performer Biographies

TOSCA Performer Biographies Making both her San Francisco Opera and role debuts as Tosca, soprano Carmen Giannattasio first received international notice after a first-place win at the 2002 Operalia competition in Paris, followed in 2007 by a tour-de-force performance as Violetta in Scottish Opera’s production of La Traviata. As equally comfortable in bel canto as she is in Verdi and Puccini, she has distinguished herself in the title role of Norma at Munich’s Bavarian State Opera, Violetta at the Metropolitan Opera, Mimì in La Bohème at the Deutsche Oper Berlin, Alice Ford in Falstaff at Teatro alla Scala and Vienna State Opera, Leonora in Il Trovatore at Vienna State Opera, and Nedda in Pagliacci at Dresden’s Semperoper and the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, among other roles. Upcoming engagements include Hélène in Les Vêpres Siciliennes at the Bavarian State Opera, Margherita in Mefistofele at the Bavarian State Opera and Chorégies d'Orange, and Amalia in I Masnadieri at the Opéra de Monte-Carlo. Tenor Brian Jagde (Mario Cavaradossi) made his San Francisco Opera debut in 2010 as Joe in La Fanciulla del West and most recently returned to the Company as Calaf in Turandot, Radames in Aida, Don José in Carmen, and Pinkerton in Madama Butterfly. Last season, Jagde made role debuts as Maurizio in Adriana Lecouvreur at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden and Froh in Das Rheingold in his first appearance with the New York Philharmonic. He also performed as Pinkerton in a house debut at Washington National Opera, and he sang for the first time at Madrid’s Teatro Real as Macduff in Macbeth and at Oper Stuttgart as Cavaradossi. -

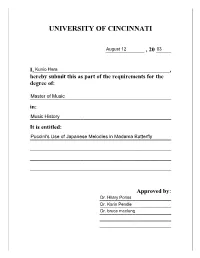

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI _____________ , 20 _____ I,______________________________________________, hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: ________________________________________________ in: ________________________________________________ It is entitled: ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ Approved by: ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ PUCCINI’S USE OF JAPANESE MELODIES IN MADAMA BUTTERFLY A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC in the Division of Composition, Musicology, and Theory of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Kunio Hara B.M., University of Cincinnati, 2000 Committee Chair: Dr. Hilary Poriss ABSTRACT One of the more striking aspects of exoticism in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly is the extent to which the composer incorporated Japanese musical material in his score. From the earliest discussion of the work, musicologists have identified many Japanese melodies and musical characteristics that Puccini used in this work. Some have argued that this approach indicates Puccini’s preoccupation with creating an authentic Japanese setting within his opera; others have maintained that Puccini wanted to produce an exotic atmosphere -

Giacomo Puccini's the Girl of the Golden West

GIACOMO PUCCINI’S THE GIRL OF THE GOLDEN WEST Links to resources and lesson plans related to Puccini’s opera, The Girl of the Golden West. The Aria Database: La fanciulla del West http://www.cambridge.org/us/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521856881&ss=exc Information on 5 arias for La fanciulla del West, including roles, voice parts, vocal range, synopsisi, with aria libretto and translation. Associated Content: "Opera Guide and Synopsis: La Fanciulla Del West, by Giacomo Puccini" http://www.associatedcontent.com/article/2285233/opera_guide_and_synopsis_la_fanciulla.html This article gives a brief introduction to the opera, lists all the characters and their voice types, and provides a lengthy synopsis. Cambridge Studies in Opera: “The Puccini Problem” http://www.cambridge.org/us/catalogue/catalogue.asp?isbn=9780521856881&ss=exc Excerpt from Alexandra Wilson’s book, “The Puccini Problem” with .pdf download. Examiner, New York: Opera Preview: La Fanciulla del West http://www.examiner.com/metropolitan-opera-house-in-new-york/opera-preview-la-fanciulla-del-west This advertisement for the Metropolitan Opera's 2010 production gives an overview of the opera. Giacomo Puccini’s La Fanciulla del West: 100th Anniversary of World Premiere http://fanciulla100.org/ Website to be launched in 2010 to celebrate the 100th anniversary of La Fanciulla del West. Glimmerglass Opera: La fanciulla del West http://www.glimmerglass.org/Productions/production_PDFs/La%20Fanciulla%20del%20West.pdf Photos of Glimmerglass Opera’s 2004 production of La fanciulla del West, co-produced with New York City Opera. Grisham College: “Puccini and New York” http://www.gresham.ac.uk/event.asp?PageId=45&EventId=570 Lecture transcript and video for 2007 Grisham College lecture by Professor Roger Parker on “Puccini and New York,” highlighting Puccini’s work composing La fanciulla del West and the Metropolitan Opera premiere. -

Vincerò! Piotr Beczala

Vincerò! Piotr Beczala ORQUESTRA DE LA COMUNITAT VALENCIANA MARCO BOEMI VINCERÒ! Ruggero Leoncavallo (1857-1919): Pagliacci (1892) 13 Recitar … Vesti la giubba 3. 29 Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924): Tosca (1900) 1 Recondita armonia 2. 47 Giacomo Puccini: La Fanciulla del West (1910) 2 E lucevan le stelle 4. 15 14 Ch’ella mi creda libero e lontano 1. 49 Francesco Cilea (1866-1950): Adriana Lecouvreur (1902) Giacomo Puccini: Edgar (1888) 3 La dolcissima effigie 2. 03 15 Orgia, chimera dall’occhio vitreo 4. 54 4 L’anima ho stanca 1. 54 5 Il russo Mèncikoff ** 1. 55 Giacomo Puccini: Gianni Schicchi (1918) 16 Avete torto … Firenzo è come un albero fiorito 3. 11 Pietro Mascagni (1863-1945): Cavalleria rusticana (1890) 6 Intanto amici … Viva il vino spumeggiante * & ** 3. 01 Giacomo Puccini: Madama Butterfly (1904/1907) 7 Mamma, quel vino è generoso (Addio alla madre) * 3. 43 17 Addio fiorito asil 1. 59 Giacomo Puccini: Manon Lescaut (1893) Giacomo Puccini: Turandot (1926) 8 Donna non vidi mai 2. 24 18 Nessun dorma ** 3. 22 9 Tra voi, belle ** 1. 30 Total playing time: 52.56 Umberto Giordano (1867-1948): Andrea Chénier (1896) Piotr Beczala, tenor 10 Come un bel dì di maggio 2. 50 11 Un dì all’azzuro spazio (Improvviso) 5. 00 * Evgeniya Khomutova, mezzo-soprano (Centre de Perfeccionament Plácido Domingo) ** Cor de la Generalitat Valenciana Umberto Giordano: Fedora (1898) 12 Amor ti vieta 1. 41 Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana Conducted by Marco Boemi My new exciting project for 2020 is my recording of Verismo arias, ‘Vincerò!’, for my partners and friends at the ‘Label of the Year’ PENTATONE. -

CHAN 3068 BOOK COVER.Qxd 16/7/07 10:47 Am Page 1

CHAN 3068 BOOK COVER.qxd 16/7/07 10:47 am Page 1 CHAN 3068(2) CHANDOS O PERA IN ENGLISH PETE MOOES FOUNDATION CHAN 3068 BOOK.qxd 16/7/07 10:52 am Page 2 Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) Otello Dramma lirico in four acts Lebrecht Collection Lebrecht Libretto by Arrigo Boito after Shakespeare, English translation by Andrew Porter Otello, a Moor, general of the Venetian army ................................................ Charles Craig tenor Desdemona, Otello’s wife ....................................................................Rosalind Plowright soprano Iago, an ensign ............................................................................................Neil Howlett baritone Emilia, Iago’s wife............................................................................Shelagh Squires mezzo-soprano Cassio, a platoon leader........................................................................Bonaventura Bottone tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ..........................................................................Stuart Kale tenor Lodovico, an ambassador of the Venetian Republic ..................................................Sean Rea bass Montano, Otello’s predecessor as Governor of Cyprus ............................Malcolm Rivers baritone Herald ....................................................................................................Gordon Traynor baritone English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus Mark Elder Giuseppe Verdi 3 CHAN 3068 BOOK.qxd 16/7/07 10:52 am Page 4 COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Time Page Act I Act II Scene 1 Scene 1 1 ‘See, the sail there!’ 4:22 [p. 84] 11 ‘Don’t give up hope, but trust in me’ 2:42 [p. 93] Chorus, Montano, Cassio, Iago, Roderigo Iago, Cassio 2 ‘Oh rejoice now!’ 2:17 [p. 85] Otello, Chorus Scene 2 3 ‘Roderigo, speak up’ 2:45 [p. 86] 12 ‘Take it; take the path to your ruin’ 0:32 [p. 94] Iago, Roderigo 13 ‘Yes, I believe in a God who has created me’ 4:25 [p. 94] 4 ‘Flame of rejoicing!’ 2:23 [p. 87] 14 ‘There she is… Cassio… your chance…’ 1:23 [p. -

The Inventory of the Dorothy Kirsten Collection #1753

The Inventory of the Dorothy Kirsten Collection #1753 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center KIRSTEN, DOROTHY 1913 - 1992 #427B Gift of the Estate of Dorothy Kirsten, 1993. Lyric soprano with Metropolitan Opera I. SCRAPBOOKS Containing newspaper and magazine items pasted in. Also reviews, publicity press releases, and programs, documenting her professional career and private life. Package 1 (First Scrapbook) 1938 - 1943. Package 2 October 1944 - August 1945. Package 3 December 1946 - September 1947. Package 4 June 1947 - April 1948. Package 5 December 1947 - December 1948. Package 6 December 1948 - July 1951. Package 7 1950 - June 1951. II. VIDEOCASSETTE Box 1 1. "Remembering Dorothy Kirsten" Kirsten, Dorothy #1753 10/8/93 - 2/6/09 Preliminary Listing I. Printed Materials [see also oversized materials]. A. Files, may include clippings, programs, correspondence, contracts, manuscripts, and magazines. Added to Box 1 1. "Early 1940s Originals." [F. 2] 2. "1942." 3. "1943 La Scala Opera Co." 4. "1947 Clippings San Francisco." 5. "1947 Grace Moore." [F. 3] 6. "1947 Originals," 4 files. [F. 3-4] 7. "January, 1948." [F. 5] 8. "April, 1948." 9. "May, 1948." 10. "Summer, 1948-June-California." 11. "September, 1948." 12. "November, 1948." 13. "November, 1948 Concerts with Martini, Lanza." [F. 6] 14. "1948 Originals." 15. "1948 Met Tour." 16. "1949 Originals." 17. "1949 Publicity." 18. "1950s Programs." [F. 7] 19. "1950s Miscellaneous." 20. "1950 Originals," 2 files. [F. 8-9] 21. "1951 Originals." [F. 10] 22. "1952 Originals." [F. 11] 23. "1953 Originals," 2 files. [F. 11-12] 24. "1954 Chapman Obituary." 25. "1954 Originals." 26. "1954 Originals, January and July." 27. -

Puccini's Music

Puccini’s Music By Sandy Thorburn If there is one composer that opera buffs think of when United States, and Madama Butterfly involves a tragic love the word “opera” is mentioned, it is Giacomo Puccini. story between an American naval captain named Pinkerton His name is synonymous to many with Italian opera. His and a Japanese geisha. Turandot is about a wild and angry world is filled with weeping Romantic tenors pleading princess in China who forces all her suitors to answer an for the beautiful soprano not to die, just when they have unanswerable riddle in order to avoid an arranged marriage. discovered that they love each other: sad, beautiful, and La Bohème is about the Romantic “Bohemian” culture of quintessentially Italian. the 19th-century Parisian Left Bank. Tosca features a fiery opera singer (played, usually, by a fiery opera singer!) who refuses to betray her love Cavaradossi to the evil Roman police chief Scarpia. Did you know? Puccini operas almost always Did Puccini find the key to never-ending popularity of his feature beautiful orchestrations that music? In 1994, Jonathan Larson paid homage to the closely follow the drama, but seldom composer and La Bohème, when he wrote his Tony Award- double the melody sung by the singer. winning musical Rent, using similar characters and storyline Often the melody played by the and even melodies from Puccini’s score! The hit musical orchestra is better, and more interesting was even made into a motion picture in 2005 using some (and more complete) than the sung of the original cast members. -

The Girl of the Golden West Performer Biographies

THE GIRL OF THE GOLDEN WEST PERFORMER BIOGRAPHIES Deborah Voight (Minnie) Deborah Voigt is hailed by the worldʼs critics and audiences as todayʼs foremost dramatic soprano. The former Adler Fellow and Merola Opera Program alumna made her main stage debut in Don Carlos and has since returned to the Company in nine subsequent productions, most recently as Amelia Anckarström in Un Ballo in Maschera (2006). In addition to the role of Amelia in the 1990 production of Un Ballo in Maschera, her other performances at San Francisco Opera include Anna (Nabucco), Elisabeth (Tannhäuser), the title role of Ariadne auf Naxos, and Sieglinde (Die Walküre); these performances in La Fanciulla del West mark her role debut as Minnie. Voigt is a regular artist at the Metropolitan Opera—recent appearances there include the roles of Chrysothemis (Elektra), Senta (Der Fliegende Holländer), Isolde (Tristan und Isolde), Leonora (La Forza del Destino), the Empress (Die Frau ohne Schatten), Sieglinde, and the title roles of Tosca, Aida, Die Ägyptische Helena, and La Gioconda. She also performs regularly with Vienna State Opera (Tosca, the title roles of Salome and Ariadne auf Naxos, the Marschallin in Der Rosenkavalier, Isolde, Brünnhilde in Siegfried); Paris Opera (Senta, Lady Macbeth in Macbeth); the Royal Opera, Covent Garden (Ariadne, the Empress in Die Frau ohne Schatten, and the title role of Die Ägyptische Helena); Lyric Opera of Chicago (Salome, Isolde, Sieglinde, Tosca), Barcelonaʼs Gran Teatre del Liceu (Maddalena in Andrea Chénier, the title role of La Gioconda, Isolde) and the Salzburg Festival (the title role of Die Liebe der Danae). The Illinois native was a gold medalist in the 1990 Tchaikovsky Competition and received first prize in Italyʼs Verdi Competition. -

Benedikt, Kristian - Tenor

Benedikt, Kristian - Tenor Biography Lithuanian tenor Kristian Benedikt has built up a reputation as one of the leading international singers of Verdi’s Otello. He sang this most demanding role more than 120 times: at Opera de Bellas Artes in Mexico, Teatro Filarmonico in Verona, Wiener Staatsoper, Bavarian State Opera Munich, at the Mariinski Theatre in St. Petersburg, Modena, Piacenza, Cagliari, Palermo, Ekaterinburg, Santiago de Chile, Vilnius, Graz, Basel, Stockholm, Latvian Opera Festival and at Victoria’s Pacific Opera, Montreal Opera, Savonlinna Festival and others. In 2018 he made his debut at the Metropolitan Opera in New York with the role of Samson (Samson et Dalila), and in 2019 he debuted as Andrea Chenier at the Trieste Teatro Verdi and as Calaf at the Teatre Colón along with Maria Guleghina. He also sang Calaf at Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre (dir. R. Willson), Samson and Herman (with Asmik Grigorian) at Vilnius City Opera, and a Gala concert in Pažaislis festival. Benedikt‘s first CD was released in 2019 by DELOS. His past engagements include Don Alvaro (La forza del destino) in Lisbon and Porto (Portugal), Herman at Vilnius City Opera and Metropolitan Opera. 2020 is market by a double debut of Kristian in Erik (Der fliegende Holländer) at Bilbao Opera with Bryn Terfel. In March 2020, he will sing Calaf and Ernani at Lithuanian National Opera and Ballet Theatre. During his latest seasons Benedikt sung at the Wiener Staatspoer (Otello), London Royal Covent Garden Opera (Canio), Mariinsky Theatre (Otello,